P. 1 Feeding Preference of the Oak Moth (Phargandia Californica) and the Possibility of Tannin Sequestration on a Diet of Costal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future: Discussion Author(S): H

The Paraguayan Chaco and Its Possible Future: Discussion Author(s): H. E., Maurice de Bunsen, R. B. Cunninghame Graham, A. Ewbank, J. W. Evans and W. Barbrooke Grubb Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep., 1919), pp. 171-178 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1780057 Accessed: 21-06-2016 12:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Tue, 21 Jun 2016 12:21:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE PARAGUAYAN CHACO AND ITS POSSIBLE FUTURE 171 already accessible. The lands in their present condition, provided that water could be secured, are estimated to carry safely five hundred cattle per Paraguayan league, and if this province could be developed in this way the total value represented would be immense. Fencing is an easy matter, as posts are abundant and almost always near at hand. The Indians make capital cow-boys and expert fencers. The wood industry at present consists chiefly in the export of tanning from the quebracho tree, but the exploitation of these forests depends entirely upon the means of conveyance. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.248,158 B2 Brown Et Al

USOO92481.58B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.248,158 B2 BrOWn et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 2, 2016 (54) HERBAL SUPPLEMENTS AND METHODS OF 2008/022O101 A1* 9, 2008 Buchwald-Werner ... A23L 1,293 USE THEREOF 424,728 2008/0268024 A1* 10, 2008 Rull Prous et al. ........... 424/439 (71) Applicant: KBS Research, LLC, Plano, TX (US) 2010, 0008887 A1 1/2010 Nakamoto et al. (72) Inventors: Kenneth Brown, Plano, TX (US); FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Brandi M. Scott, Plano, TX (US) FR 2770228 A1 * 4, 1999 WO 2012131728 A2 10, 2012 (73) Assignee: KBS RESEARCH, LLC, Plano, TX (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Zotte et al., Dietary inclusion of tannin extract from red quebracho patent is extended or adjusted under 35 trees (Schinopsis spp.) in the rabbit meat production, 2009, Ital J U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. Anim Sci., 8:784-786.* Becker, K., et al. “Effects of dietary tannic acid and quebracho tannin on growth performance and metabolic rates of common carp (21) Appl. No.: 14/072,502 (Cyprinus carpio L.), Aquaculture, May 15, 1999, vol. 175, Issues Filed: Nov. 5, 2013 3-4, pp. 327-335. (22) Durmic, Z. et al. “Bioactive plants and plant products: Effects on Prior Publication Data animal function, health and welfare'. Animal Feed Science and Tech (65) nology, Sep. 21, 2012, vol. 176, Issues 1-4, pp. 150-162. US 2014/01.41108A1 May 22, 2014 Search Report and Written Opinion mailed Jan. 29, 2014, in corre sponding International Patent Application No. -

WO 2017/203429 Al 30 November 2017 (30.11.2017) W !P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/203429 Al 30 November 2017 (30.11.2017) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, A61K36/87 (2006.01) A61K8/00 (2006.01) KM, ML, MR, NE, SN, TD, TG). (21) International Application Number: Published: PCT/IB2017/053035 — with international search report (Art. 21(3)) (22) International Filing Date: 23 May 2017 (23.05.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Langi English (30) Priority Data: P201630673 24 May 2016 (24.05.2016) ES (71) Applicants: UNIVERSITAT POLITECNICA DE CATALUNYA [ES/ES]; Jordi Girona, 3 1, 08034 Barcelona (ES). CONSORCI ESCOLA TECNICA D'IGUALADA [ES/ES]; Av. Pla de la Massa, 8, 08700 Igualada (ES). (72) Inventors: ANNA, Bacardit Dalmases; Av. Vilanova, 55, 2, 08700 Igualada (ES). LUIS, Olle Otero; C. Joan Lla- cuna Carbonell, 1, 08700 Igualada (ES). SILVIA, Sorolla Casellas; Av. Balmes, 14, ler. la., 08700 Igualada (ES). CONCEPCI0, Casas Sole; C. Pierola, 5, escala A, 3er. 2a., 08700 Igualada (ES). (74) Agent: VIDAL, Maria Merce; C. Consell de Cent, 322, 08007 Barcelona (ES). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY,TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Intake of Water Containing Condensed Tannin by Cattle and Sheep Scott L

Rangeland Ecol Manage 61:354–358 | May 2008 Research Note Intake of Water Containing Condensed Tannin by Cattle and Sheep Scott L. Kronberg Author is Animal Scientist, US Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory, Mandan, ND 58554, USA. Abstract Ingestion of small amounts of condensed tannin (CT) by ruminants can prevent bloat, improve nitrogen retention, and reduce excretion of urea, a precursor of ammonia and the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide. Because grasses and many forbs don’t contain CT, it is desirable to find a reliable way to have ruminant livestock ingest small amounts of CT when they consume high-quality forage. Putting CT in their drinking water may be a reliable approach, but only if all animals drink enough to meet their requirements for water. Therefore, objectives of this study were to determine the amount of variation in intake of water containing different amounts of CT when this was the only water available, and if cattle and sheep would drink water with CT in it if offered tap water simultaneously. Animals were penned or pastured individually, fed twice daily (first cattle and sheep trial) or grazed (second cattle trial) and had ad libitum access to tannin water, tap water, or both. Liquid intake was measured daily. Steers drank tannin solutions (mean daily intake 49.7–58.3 kg), but variation in intake among steers was higher than for tap water (SD were 44%–58% greater for the two most concentrated tannin solutions). At the highest concentration of tannin, steers ingested 2.3% of their daily feed intake in CT. -

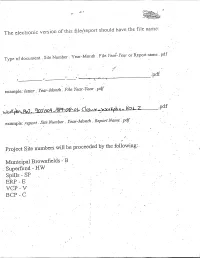

Fear Or Report Name. Pdf

S==dz 3 fate The electronic version of this file/report should have the file name: Type of document . S jte Number . Year-Month . File J'ea.2- Fear or Report name. pdf I , .pdf example: letter. Year-Month. File Year-Year . pdf worY-fhn. R\0... 905-004. /989- 02-01· Cloiu re-z>), 41*18 4- VOLZ .pdf . example:, report . Site Number . Year-Month . Report Name . pdf · · - Project Site numbers ·will be proceeded by the following:. Municipal Brownfields -' B . Superfund - HW Spills - SP ER:P-E VCP -V BCP-C 1 Engineering Report 1 1 PALMER STREET LANDFILL 1 CLOSURE/POST-CLOSURE PLAN (EPA ID NYD002126910) 1 VOLUME 11 : APPENDICES 1 Y 1 2 1 Moench Tanning Company 1 Diision of Brown Group, Inc. Gowanda, New York J 1 1 October 4. 1985 Revised November 1987 Revised February 1989 1 Revised August 1989 Project No. 0605-12-1 1 IRNI ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERS, SCIENTISTS & PLANNERS 1 1 1 =Isr 1 MOENCH TANNING COMPANY PALMER STREET LANDFILL CLOSURE/POST-CLOSURE PLAN 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 VOLUME 1 Page 1 1.0 FACILITY DESCRIPTION ........... 1 1 1 1 1.1 General Description ........... ... 1.1.1 Products Produced ........ 1 1 1.1.2 Site Description ........ 1 2 1 1 2 1.2 Waste Generation ........./. .. 1.2.1 Maximum Hazardous Waste Inventory 1 4 1.3 Landfill Operation ........... 1 5 1 6 1 1.4 Topographic Map ........... .. 1.5 Facility Location Information ...... 1 6 1.5.1 Seismic Standard ........ .. 1 6 1 1.5.2 Floodplain Standard ....... 1 -6 1 7 1.5.3 Demonstration of Compliance .. -

Ecological and Social Consequences of the Forest Transition Theory As

Land Use Policy 51 (2016) 8–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Land Use Policy jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landusepol Ecological and social consequences of the Forest Transition Theory as applied to the Argentinean Great Chaco a,b,∗ b b Silvia D. Matteucci , Mariana Totino , Pablo Arístide a National Research Council of Argentina, Argentina b Landscape Ecology and Environment Team, Buenos Aires University, Argentina a r a t i b s c t l e i n f o r a c t Article history: Forest transition is the change from net deforestation to net reforestation. According to the Forest Tran- Received 17 August 2015 sition Theory (FTT) in its original form, reforestation is triggered by the last stage of socio-economic Received in revised form 13 October 2015 development, when the rural population migrates to urban areas, and forest cover expands naturally on Accepted 30 October 2015 abandoned agricultural fields. The assumptions underlying the FTT have been changed to extrapolate it Available online 19 November 2015 to the Argentinean Great Chaco (AGC). It is suggested that Indigenous people and low income peasants, who use land inefficiently, should migrate to the urban areas in search of a better life quality. Thus, the Keywords: abandoned lands could be used for conservation, while the most suitable soils could be destined for Deforestation Development food production. However, the subtropical forests in the AGC are highly vulnerable to desertification, as a consequence of rainfall irregularity and high summer evaporation rates. The probability exists that Indigenous people Low-income peasants forest recovery does not occur in time scales relevant for conservation. -

EXTERNAL GENITALIC MORPHOLOGY and COPULATORY MECHANISM of CYANOTRICHA NECYRIA (FELDER) (DIOPTIDAE) Genitalic Structure Has Been

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 42(2). 1988, 103-115 EXTERNAL GENITALIC MORPHOLOGY AND COPULATORY MECHANISM OF CYANOTRICHA NECYRIA (FELDER) (DIOPTIDAE) JAMES S. MILLER Curatorial Fellow, Department of Entomology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024 ABSTRACT. External genitalia of Cyanotricha necyria (Felder) exhibit characters that occur in the Notodontidae and Dioptidae. These provide further evidence that the two groups are closely related. Dissection of two C. necyria pairs in copula revealed two features unique among copulatory mechanisms described in Lepidoptera. First, only the male vesica, rather than the aedoeagus and vesica, are inserted into the female. Secondly, during copulation the female is pulled into the male abdomen, and his eighth segment applies dorsoventral pressure on the female's seventh abdominal segment. This mechanism is facilitated by a long membrane between the male eighth and ninth abdominal segments. The first trait is probably restricted to only some dioptid species, while the second may represent a synapomorphy for a larger group that would include all dioptids, and all or some notodontids. Additional key words: Noctuoidea, Notodontidae, Josiinae, functional morphology. Genitalic structure has been one of the most important sources of character information in Lepidoptera systematics. Taxonomists often use differences in genitalic morphology to separate species, and ho mologous similarities have provided characters for defining higher cat egories in Lepidoptera classification (Mehta 1933, Mutuura 1972, Dug dale 1974, Common 1975). Unfortunately, we know little concerning functional morphology of genitalia. A knowledge of function may aid in determining homology of genitalic structures, something that has proved to be extremely difficult and controversial. -

Urban Pest Management: a Report REFERENCE COP~ for LIBRAR'l USE ONLY

This PDF is available from The National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=19809 Urban Pest Management: A Report (1980) Pages Committee on Urban Pest Management; Environmental 304 Studies Board; Commission on Natural Resources; Size National Research Council 5 x 8 ISBN 0309031257 Find Similar Titles More Information Visit the National Academies Press online and register for... Instant access to free PDF downloads of titles from the NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL 10% off print titles Custom notification of new releases in your field of interest Special offers and discounts FROM THE ARCHIVES Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. To request permission to reprint or otherwise distribute portions of this publication contact our Customer Service Department at 800-624-6242. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Urban Pest Management: A Report http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=19809 REFERENCE COP~ fOR LIBRAR'l USE ONLY lliQM1~ ..Nationa[ AcademJ Press The National Academy Press was created by the National Academy of Sciences to publish the reports issued by the Academy and by the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council, all operating under the charter granted to the National Academy of Sciences by the Congress of the United States. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Urban Pest Management: A Report http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=19809 IJrbaa Pesl M aaagemeal A Report Prepared by the COMMITI'EE ON URBAN PEST MANAGEMENT Environmental Studies Board Commission on Natural Resources National Research Council ,. -

Coast Live Oak, Quercus Agrifolia, Susceptibility and Response to Goldspotted Oak Borer, Agrilus Auroguttatus, Injury in Southern California

G Model FORECO-12550; No. of Pages 14 ARTICLE IN PRESS Forest Ecology and Management xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Coast live oak, Quercus agrifolia, susceptibility and response to goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus auroguttatus, injury in southern California Tom W. Coleman a,∗, Nancy E. Grulke b,1, Miles Daly c, Cesar Godinez b, Susan L. Schilling b, Philip J. Riggan b, Steven J. Seybold d a USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, 602 S. Tippecanoe Ave., San Bernardino, CA 92408, USA b USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 4955 Canyon Crest Drive, Riverside, CA 92507, USA c 1927 Goss St., Boulder, CO 80302, USA d Chemical Ecology of Forest Insects, USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 720 Olive Drive, Suite D, Davis, CA 95616, USA article info abstract Article history: Oak mortality is often associated with a complex of decline factors. We describe the morphological and Received 11 November 2010 physiological responses of coast live oak, Quercus agrifolia Née, in California to an invasive insect, the Received in revised form 6 February 2011 goldspotted oak borer (GSOB), Agrilus auroguttatus Schaeffer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), and evaluate Accepted 7 February 2011 drought as a potential inciting factor. Morphological traits of 356 trees were assessed and physiological Available online xxx traits of 70 of these were monitored intensively over one growing season. Morphological characteristics of tree health included crown thinning and dieback; bole staining resulting from larval feeding; den- Keywords: sity of GSOB adult exit holes; and holes caused by woodpecker feeding. -

Modified Tannin Extracted from Black Wattle Tree As Environmental-Friendly Antifouling Pigment

Modified Tannin Extracted from Black Wattle Tree as Environmental-Friendly Antifouling Pigment Rafael S. Peres,1 Elaine Armelin,2,3 Carlos Alemán2,3 and Carlos A. Ferreira,1 1LAPOL/PPGE3M, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Av. Bento Gonçalves 9500, 91501-970, Porto Alegre, Brazil 2 Departament d’Enginyeria Química, ETSEIB, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Av. Diagonal 647, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 3 Centre for Research in Nano-Engineering, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Campus Sud, Edifici C’, C/Pasqual i Vila s/n, Barcelona E-08028, Spain. Abstract The use of modified black wattle tannin as antifouling pigment is reported in this work. Mixture of tannin adsorbed in activated carbon (soluble fraction of tannin) and low soluble fraction of tannin was used as antifouling pigment. The soluble rosin resin was used as paint matrix. 13C NMR analysis confirm the modification of black wattle tannin through the cleavage of tannin interflavonoid bonds. FTIR spectra indicates the presence of tannin in the formulated antifouling coating even after 7 months of its exposure in marine environment. Water contact angle analysis shows the hydrophilic characteristic of tannin antifouling coating surface. Immersion tests at Badalona port in Mediterranean Sea shows the high antifouling efficiency of TAN coating, comparable to the commercial paint, until 7 months. The use of a natural black wattle tannin, without its complexation with metals, can eliminate the release of metals and other toxic biocides to the marine environment. Keywords: -

An Integrative Secondary Life Science Curriculum Using Select Ecological Topics Pertaining to Forest Ecosystems of North Coast California

AN INTEGRATIVE SECONDARY LIFE SCIENCE CURRICULUM USING SELECT ECOLOGICAL TOPICS PERTAINING TO FOREST ECOSYSTEMS OF NORTH COAST CALIFORNIA by Melinda Bailey A Project Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Master of Science in Biology Committee Membership Dr. Jeffrey White, Chair Dr. Sean Craig, Committee Member Dr. Erik Jules, Committee Member Dr. Susan Edinger Marshall, Committee Member Dr. Michael Mesler, Graduate Coordinator December 2014 ABSTRACT AN INTEGRATIVE SECONDARY LIFE SCIENCE CURRICULUM USING SELECT ECOLOGICAL TOPICS PERTAINING TO FOREST ECOSYSTEMS OF NORTH COAST CALIFORNIA Melinda Bailey Place-based education is an instructional approach that engages students with their local environment, which can enrich the educational experience and improve scientific literacy. This project is a place-based secondary-level life science curriculum incorporating important ecological concepts using select forest types of the North Coast of California, USA. The North Coast has a rich natural history and many schools are situated near forests. This curriculum is multidimensional and includes structured units for middle school and high school students presented in three thematic modules: general forest ecology, coast redwoods, and oak woodlands. Units are preceded by a companion piece for each module that embeds some of the latest scientific research intended to broaden a teachers’ previous knowledge. Information is approached from different spatial and temporal scales and designed for flexibility in order to fit the needs of local educators. Information was routinely sourced from primary scientific literature and professional reports, which often can be difficult to obtain and comprehend by the non-specialist. Components include figures and select data, which are integrated into student lessons that offer a unique conduit between scientists, science teachers, and science students. -

A Sex Pheromone in the California Oakworm Phryganidia Californica Packard (Dioptidae)

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 38(3),1984,176-178 A SEX PHEROMONE IN THE CALIFORNIA OAKWORM PHRYGANIDIA CALIFORNICA PACKARD (DIOPTIDAE) MICHAEL E. HOCHBERG AND W. JAN A. VOLNEY Division of Entomology and Parasitology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 ABSTRACT. California oak worm (Phryganidia cali/arnica) virgin females confined to sticky traps attracted significantly more males than unbaited control traps. This dem onstrates the presence of a sex attractant in this species. The California oakworm (COW), Phryganidia californica Packard, the only species of the family Dioptidae in America north of Mexico, is a major defoliator of oaks in California (Essig, 1958; Brown & Eads, 1965). Previous studies (Harville, 1955; Sibray, 1947) have shown that COW populations erupt sporadically, but the causes of these eruptions are presently unknown. Attractive pheromones, should they exist, could provide a means of detecting sparse populations and incipient out breaks and determining the distribution of this species (Daterman, 1978; Carde, 1979). Here we report results that indicate the presence of a female pro duced sex pheromone in this species. MATERIALS AND METHODS The study was carried out in October 1982 in a ca. % hectare stand of California live oaks (Quercus agrifolia Nee) on the University of California campus, Berkeley. Adults used in these trials were field collected pupae which were confined individually to 90 x 23 mm shell vials plugged with cotton wool. The insects were reared under a natural photoperiod in the laboratory and allowed to emerge in these vials. Pherocon lC® (Zoecon Corp., Palo Alto, CA) sticky traps were used in all trials. Traps were baited by confining one virgin female to a cylindrical (6 x 12 mm) steel mesh cage suspended from the trap roof.