The International Impact of Lessing's Nathan the Wise David G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spartacus Revolt January 1919

The Spartacus Revolt January 1919 The war was over, Kaiser Wilhelm had fled and revolutionaries were roaming the streets. The people of Germany now had to decide what kind of Republic the new Germany would be. Would Germany become a peaceful law-abiding democracy like Britain, with power shared between the upper, middle and working classes? Or would a violent revolution sweep away the past and create a communist country completely dominated by the workers? What were the options? The Social Democrats, led by Ebert, wanted Germany to become a law-abiding parliamentary democracy like Britain, where every German - rich or poor - would be entitled to a say in how the country was run, by voting in elections for a parliament (Reichstag) which would make the laws. The Spartacus League - (Spartacists aka communists) - on the other hand wanted Germany to become a communist country run by, and for, the workers; they wanted power and wealth to be taken away from the old ruling elite in a violent revolution and for Germany to then be run by Workers Councils - or Soviets. The Spartacists wanted a new kind of political system - communism, a system where the country would be run for and on behalf of the workers, with all wealth and power being removed from the previous rulers. Ebert of the SPD Spartacus League Freecorps Soldier . 1 After the Kaiser had gone… With revolutionary workers and armed ex-soldiers on the loose all over Germany, Ebert and the Social Democrats were scared. He wanted to make sure that the people of Germany understood what the Social Democrats would give them if they were in charge of Germany. -

Cambridge Companion Shakespeare on Film

This page intentionally left blank Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays are increasingly popular and now figure prominently in the study of his work and its reception. This lively Companion is a collection of critical and historical essays on the films adapted from, and inspired by, Shakespeare’s plays. An international team of leading scholars discuss Shakespearean films from a variety of perspectives:as works of art in their own right; as products of the international movie industry; in terms of cinematic and theatrical genres; and as the work of particular directors from Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles to Franco Zeffirelli and Kenneth Branagh. They also consider specific issues such as the portrayal of Shakespeare’s women and the supernatural. The emphasis is on feature films for cinema, rather than television, with strong cov- erage of Hamlet, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A guide to further reading and a useful filmography are also provided. Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. He has worked as a textual adviser on several feature films including Shakespeare in Love and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. He is co-editor of Shakespeare: An Illustrated Stage History (1996) and two volumes in the Players of Shakespeare series. He has also edited Oscar Wilde’s plays. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO SHAKESPEARE ON FILM CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Old English The Cambridge Companion to William Literature Faulkner edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Philip M. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Khachaturian BL1 V0 Brilliant 21/12/2011 16:55 Page 1

9256 Khachaturian_BL1_v0_Brilliant 21/12/2011 16:55 Page 1 9256 KH ACH ATURIAN GAY ANE H · SPAR TACUS Ball et Su ites BOLSHOI THEATRE O RCHESTRA EVGENY SVETLANOV Aram Khachaturian 1903 –1978 Khachaturian: Suites from Gayaneh and Spartacus Gayaneh – Ballet Suite Aram Ilyich Khachaturian was born in Tbilisi, Georgia, to a poor Armenian family. 1 Dance of the Rose Maidens 2’42 Although he was fascinated by the music he heard around him as a child, he remained 2 Aysha’s Dance 4’22 self-taught until the early 1920s, when he moved to Moscow with his brother, who had 3 Dance of the Highlanders 1’57 become stage director of the Second Moscow Art Theatre. Despite this lack of formal 4 Lullaby 5’53 training, Khachaturian showed such musical promise that he was admitted to the 5 Noune’s Dance 1’44 Gnessin Institute, where he studied cello and, from 1925, composition with the 6 Armen’s Var 1’58 Institute’s founder, the Russian-Jewish composer Mikhail Gnessin. In 1929, 7 Gayaneh’s Adagio 4’00 Khachaturian entered the Moscow Conservatory where he studied composition with 8 Lezghinka 2’57 Nikolai Myaskovsky and orchestration with Sergei Vasilenko. He graduated in 1934 9 Dance with Tambourines 2’59 and wrote most of his important works – the symphonies, ballets and principal 10 Sabre Dance 2’30 concertos – over the following 20 years. In 1951, he became professor at the Gnessin State Musical and Pedagogical Institute (Moscow) and at the Moscow Conservatory. Spartacus – Ballet Suite He also held important posts at the Composers’ Union, becoming Deputy Chairman of 11 Introduction – Dance of the Nymphs 6’04 the Moscow branch in 1937 and Vice-Chairman of the Organising Committee of Soviet 12 Aegina’s Dance 4’00 Composers in 1939. -

An Introduction to Aram Khachaturian

CHANDOS :: intro CHAN 2023 an introduction to Aram Khachaturian :: 17 CCHANHAN 22023023 BBook.inddook.indd 116-176-17 330/7/060/7/06 113:16:543:16:54 Aram Il’yich Khachaturian (1903–1978) Four movements from ‘Gayaneh’* 12:31 Classical music is inaccessible and diffi cult. 1 I Sabre Dance 2:34 It’s surprising how many people still believe 2 III Dance of the Rose Maidens 2:23 the above statement to be true, so this new series 3 V Lullaby 4:39 from Chandos is not only welcome, it’s also very 4 VIII Lezghinka 2:55 necessary. I was lucky enough to stumble upon the Suite from ‘Masquerade’* 16:27 wonderful world of the classics when I was a 5 I Waltz 3:57 child, and I’ve often contemplated how much 6 II Nocturne 3:31 poorer my life would have been had I not done so. As you have taken the fi rst step by buying this 7 III Mazurka 2:41 CD, I guarantee that you will share the delights 8 IV Romance 3:08 of this epic journey of discovery. Each CD in the 9 V Galop 3:07 series features the orchestral music of a specifi c composer, with a selection of his ‘greatest hits’ Suite No. 2 from ‘Spartacus’* 20:44 CHANDOS played by top quality performers. It will give you 10 1 Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia 8:52 a good fl avour of the composer’s style, but you 11 2 Entrance of the Merchants – Dance of a Roman won’t fi nd any nasty surprises – all the music is Courtesan – General Dance 5:30 instantly accessible and appealing. -

Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview and Major Papers 4-2009 Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Peirce, Merle Kenneth, "Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films" (2009). Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview. 19. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSGRESSIVE MASCULINITIES IN SELECTED SWORD AND SANDAL FILMS By Merle Kenneth Peirce A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Individualised Masters' Programme In the Departments of Modern Languages, English and Film Studies Rhode Island College 2009 Abstract In the ancient film epic, even in incarnations which were conceived as patriarchal and hetero-normative works, small and sometimes large bits of transgressive gender formations appear. Many overtly hegemonic films still reveal the existence of resistive structures buried within the narrative. Film criticism has generally avoided serious examination of this genre, and left it open to the purview of classical studies professionals, whose view and value systems are significantly different to those of film scholars. -

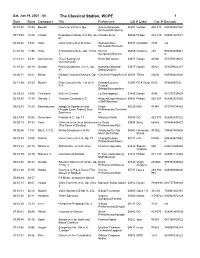

Sat, Jun 19, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Jun 19, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:30 Borodin Overture to Prince Igor Suisse Romande 06999 London 430 219 028943021920 Orchestra/Ansermet 00:13:0012:48 Chopin Polonaise Fantasy in A flat, Op. Claudio Arrau 00246 Philips 412 610 028941261021 61 00:26:48 33:08 Harty Violin Concerto in D minor Holmes/Ulster 00736 Chandos 8386 n/a Orchestra/Thomson 01:01:2611:55 Holst A Hampshire Suite, Op. 28 No. Munich 06405 Classico 284 570964498641 2 Symphony/Bostock 5 01:14:21 03:31 Anonymous Three Settings of Ronn McFarlane 02637 Dorian 90186 053479018625 Greensleeves 01:18:5240:19 Dvorak Piano Quintet No. 2 in A, Op. Kubalek/Lafayette 03577 Dorian 90221 053479022127 81 String Quartet 02:00:41 09:27 Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture, Op. Cincinnati Pops/Kunzel 06108 Telarc 80595 089408059520 9 02:11:0827:20 Mozart Flute Concerto No. 1 in G, K. Galway/Lucerne 01257 RCA Victor 6723 07863567232 313 Festival Strings/Baumgartner 02:39:2819:00 Telemann Suite in G minor La Stravaganza 01886 Denon 9398 081757939829 02:59:58 15:35 Stamitz, J. Trumpet Concerto in D Hardenberger/Academ 00883 Philips 420 203 028942020320 y SMF/Marriner 03:16:3310:20 Khachaturian Adagio of Spartacus and Royal 00226 EMI 47348 077774734820 Phrygia (Love Theme) from Philharmonic/Temirkan Spartacus ov 03:27:5330:50 Schumann Fantasy in C, Op. 17 Maurizio Pollini 09743 DG 429 372 028942937222 04:00:13 07:33 Verdi Overture to La forza del destino La Scala 03534 Sony 68468 074646846827 (The Force of Destiny) Philharmonic/Muti 04:08:4611:07 Bach, C.P.E. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Nov 08, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 08:51 Chopin Barcarolle in F sharp, Op. 60 Krystian Zimerman 01632 DG 423 090 028942309029 00:11:2108:33 Mozart Symphony No. 32 in G, K. 318 Amsterdam Baroque 02425 Erato 45714 022924571428 Orchestra/Koopman 00:20:5438:20 Schubert String Quartet No. 14 in D Jasper String Quartet 10899 Sono 92152 053479215222 minor, D. 810 "Death and the Luminus Maiden" 01:00:44 16:39 Elgar Cockaigne Overture (In London Winnipeg 05153 CBC 5176 059582517628 Town,) Op. 40 Symphony/Tovey 01:18:2310:51 Bizet Children's Games, Op. 22 Concertgebouw/Haitink 01008 Philips 416 437 028941643728 (Jeux d'enfants) 01:30:14 29:17 Franck Violin Sonata in A Midori/McDonald 04874 Sony 63331 n/a 02:01:0115:02 Handel Concerto Grosso in G minor, Academy of Ancient 05049 Harmonia 907228/2 093046722821 Op. 6 No. 6 Music/Manze Mundi 9 02:17:0311:08 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 Orchestra of the 03176 Philips 420 812 028942081222 Vienna People's Opera/Bauer-Theussl 02:29:11 29:49 Finzi Clarinet Concerto, Op. 31 Stoltzman/Guildhall 12053 RCA Victor 60437 090266043729 String Ensemble/Salter Red Seal 03:00:3016:01 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 10 in G, Op. Gyorgy Cziffra 02744 EMI 67366 077776736624 14 No. 2 03:17:31 09:32 Vivaldi Flute Concerto in D, RV 428 "Il Davis/Camerata of St. 00881 Omega 1012 N/A cardellino" Andrew/Friedman 03:28:0331:13 Rubinstein, Piano Sonata No. -

New Museum and Rhizome Present Commissioned Performances During the Month of November Performances by Public Movement and Wu

TEL +1 212.219.1222. FAX +1 212.431.5326. newmuseum.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 21, 2011 PRESS CONTACTS: Gabriel Einsohn, Communications Director [email protected] Andrea Schwan, Andrea Schwan Inc. [email protected] New Museum and Rhizome Present Commissioned Performances During the Month of November Performances By Public Movement and Wu Tsang Will Evolve Into Works for the 2012 New Museum Triennial this February New York, NY…The New Museum, in conjunction with Rhizome, is pleased to present four commissioned performances by Public Movement, Wu Tsang; Spartacus Chetwynd; and Nils Bech, Bendik Giske and Sergei Tcherepnin during the month of November 2011, as part of Performa 11. This November, Public Movement and Wu Tsang will continue their Museum as Hub residencies with two works for Performa 11. Artist residencies for the 2012 New Museum triennial began in February 2011. The action and research group Public Movement (established Tel Aviv), spent one month meeting with artists, 9/11 memorial designers, Park51 staff, government officials, Public Movement, A march, a manifestation, a memorial ceremony, a guided tour and a NYPD officers, and others to develop a project party. 18 April 2009. Photo: Tomasz Pasternak for New York. This November, Public Movement will present Positions, a public action that brings people together in Washington Square Park and Union Square South to embody their preferences, beliefs, and aspirations in a choreographed demonstration. A newly commisioned work Rally will happen in April 2012 in New York City, details to follow. Wu Tsang used the New Museum theater as studio and discussion space, culminating in a series of public programs that informed the development of a new ensemble work. -

Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography Jennifer Gerrish University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Gerrish, Jennifer, "Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 511. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/511 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/511 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography Abstract This dissertation explores echoes of the triumviral period in Sallust's Histories and demonstrates how, through analogical historiography, Sallust presents himself as a new type of historian whose "exempla" are flawed and morally ambiguous, and who rejects the notion of a triumphant, ascendant Rome perpetuated by the triumvirs. Just as Sallust's unusual prose style is calculated to shake his reader out of complacency and force critical engagement with the reading process, his analogical historiography requires the reader to work through multiple layers of interpretation to reach the core arguments. In the De Legibus, Cicero lamented the lack of great Roman historians, and frequently implied that he might take up the task himself. He had a clear sense of what history ought to be : encomiastic and exemplary, reflecting a conception of Roman history as a triumphant story populated by glorious protagonists. In Sallust's view, however, the novel political circumstances of the triumviral period called for a new type of historiography. To create a portrait of moral clarity is, Sallust suggests, ineffective, because Romans have been too corrupted by ambitio and avaritia to follow the good examples of the past. -

Leadership Lessons from Spartacus

LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM SPARTACUS Spartacus was a Thracian gladiator, who led a slave revolt and defeated the Roman forces several times as he marched his army up and down the Italian peninsula until he was killed in battle in April 71 BC. He is a figure from history who has inspired revolutionaries and filmmakers, although scholars do not have significant amounts of information about him. Only accounts from a few ancient writers have survived to this day, and none of these reports were written by Spartacus or his supporters. Background According to the main two sources at the time, Appian of Alexandria and Plutarch of Chaeronea, Spartacus was born around 111 BC. in Thrace, whose boundaries today would encapsulate parts of Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. This was an area in Southeast Europe that the Roman’s were often trying to subjugate in the first century. Spartacus appears to have served in a Roman auxiliary unit for a time, and he either deserted or became an insurgent against the Romans. He was therefore captured and forced into enslavement. Due to his strength and stature, he was sold as a slave to Lentulus Batiatis, owner of the gladiatorial school, Ludus in Capua, 110 miles from Rome. Spartacus was considered a heavyweight gladiator called a “murmillo”. However, Spartacus was a rebel. In 73 BC, Spartacus was among a group of 78 gladiators who plotted an escape from Ludus. Spartacus and his co-leaders, Gaul’s Oenomaus and Crixus broke out of the barracks, seized kitchen utensils, and took several wagons of weapons and armour. -

The Woman and the Gladiator on Television in the Twenty-First Century

NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Conference Proceedings Volume Two REDIRECTING THE GAZE: THE WOMAN AND THE GLADIATOR ON TELEVISION IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY © Fiona Hobden, University of Liverpool and Amanda Potter, Open University INTRODUCTION Every woman loves a gladiator. This common knowledge underpins the first-century CE Roman poet Juvenal’s satirical portrait of Eppia, the runaway senator’s wife who abandoned her husband and family because she loved the ‘steel blade’, and whose life story should persuade Postumus away from the insanity of marriage, lest he find himself raising a gladiator’s son (Satire 6.80-113).1 And its broader truth is suggested in a boast made in graffiti at Pompeii that ‘Cresces the net-fighter is doctor to the night-time girls, the day-time girls, and all the others’ (CIL IV.4353).2 While there may be elements of fantasy in both proclamations, the satirist and seducer both trade on the allure of the gladiator to susceptible women. Sexual desire arises, moreover, in moments of viewing. Thus, for Ovid’s predatory lover, the games, where women ‘come to see and to themselves be seen’, offer a prime occasion to pursue an erotic advantage, as ‘Venus’s boy’ fights upon the forum sands (Ars Amatoria 1.97-9, 163-70). And it was the passing glimpse of a gladiator that led Faustina to conceive a passion that allegedly resulted in the birth of her gladiator-emperor son, Commodus (Historia Augusta, ‘Life of Marcus Aurelius’ 19.1-2). In the Roman imagination, visual encounters spark female desire; sexual encounters follow.