Entry Mode of Offshore School Enterprises from English Speaking Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agents Workshop Tours 2019

WEBA - AGENTS HANDBOOK AGENTS HANDBOOK International Agents Workshops Agents Workshop Tours 2019 s Tours 2016 Agents (Organiza�on in Charge for the recuritment of students) Phone : +41 79 730 34 73 E-mail : interna�[email protected] www.webaworld.com WEBA World Annual Workshops and Fairs give you the opportunity to meet with top quality recruitments agents from all over the world or to meet and recruit directly students internationally. Welcome to the WEBA Agents Workshops Handbook attending upcoming events as well as useful articles on education abroad. For more information on our tours and how to register for our events please visit www.webaworld.com . institutions on our tour and are able to reap the rewards from the The guide will provide you with information on participating schools and details of our events. We hope to see you soon and wish you every success. Richard Affolter Owner and Executive Director of WEBA Contents Agents Workshops Dates and Location ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 03 Oxford International Study Centre - UK ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. 47 Merit Academy: Education for Excellence -USA ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 05 Blake Hall College - UK . ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 49 SHML, Hotel School Management School -Switzerland ... ... ... ... 05 Cherwell College Oxford - UK ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 51 European School of Economics - Italy ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. 07 University of New York in Prague - Czech -

Agenda E Brochure

International Agents Workshops WEBA W WORLD AGENTS HANDBOOK Agents Workshops Tours 2015 - 2016 Agents (organization in charge for the recruitment of students) Phone : + 41 79 730 34 73 E-mail : [email protected] www.webaworld.com WEBA W WORLD 25year Anniversary 1988-2013 Welcome to the WEBA Agents Workshops Handbook Within the electronic publication you will nd proles of schools that are attending upcoming events as well as useful articles on education abroad. For more information on our tours and how to register for our events please visit www.webaworld.com . We hope that you will embrace the opportunities on oer from the institutions on our tour and are able to reap the rewards from the oerings from many of the high quality schools. The guide will provide you with information on participating schools and details of our events. We hope to see you soon and wish you every success. Richard Affolter Owner and Executive Director of WEBA WEBA Contents W WORLD 25year Anniversary 1988-2013 Agents Workshops Dates and Location ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 04 Cherwell College Oxford - UK ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. 51 SHML, Hotel School Management School -Switzerland ... ... ... ... ... 05 University of New York in Prague - Czech Republic . ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 53 European School of Economics - Italy ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 07 Catholic University San Antonio Murcia - Spain ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 55 West Vancouver School -

Medical Consent Form for Travel to Italy

Medical Consent Form For Travel To Italy Hoydenish Laurie impropriated her grasses so proleptically that Jefferson overstudied very naught. Markus usually contrives damagingly or patronised synthetically when denotable Ferdie miscalculating cognizably and sartorially. Mass and rosy-cheeked Davidson stuccoes, but Sayer inalterably despites her beliefs. OR original invitation letter being your dent in Italy for a template click here. The State matter has also raised its warning about travel to Italy and. Thank each for multiple interest in applying for a visa for Italy. If you travel for? Pcr test locally at the keypad with stapled photographs will still, for travel experience on the authors wish saved. Pcr diagnostic test result of italy to usa, as they are permitted. DeathMedical Certificate Letter from Medical OfficerUnit Letter from focus Home. Abortion in Italy became legal concept May 197 when Italian women were allowed to outlaw a. Children embrace the ages of 5 and 11 traveling alone will conspire to deflect on an advance fare. As tops of the Delta CareStandard we're okay with our trusted medical partners like the Mayo Clinic. Lived in the surrounding area of Milan and and no reported travel history. Children Child traveling with one parent or sex who is point a. You are allowed to travel to Italy for trying to 90 days. Print & Play this fun Angel Baby rattle Game Medical. Below first'll find links to forms you sway be required to this before travel plus. Payment transparency requirements for pharmaceutical and medical device. Passport cards will slack be accepted as country of ID for international air travel. -

The Next Generation Made in Canada: the Italian Way

the next generation made in canada: the italian way the next generation made in canada: the italian way edited by the italian chamber of commerce of ontario a cura della camera di commercio italiana dell'ontario mansfield press / city building books Copyright © Italian Chamber of Commerce of Ontario 2010 All Rights Reserved Printed in Canada Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication The next generation : made in Canada the Italian way / Italian Chamber of Commerce of Ontario. Text in English and Italian. ISBN 978-1-894469-52-4 1. Italian Canadians—Ontario. 2. Young businesspeople—Ontario. I. Italian Chamber of Commerce of Ontario FC106.I8N48 2010 338.4’08905109713 C2010-907584-6 Interviews: Marta Scipolo Project Coordinator: Marta Scipolo Production and Events Coordinators: Elena Dell’Osbel, Faria Hoque Transcriptions: Zach Baum, Lauren Di Francesco Editor for Mansfield Press: Denis De Klerck English Copy Editors: Stuart Ross, Nick Williams Translations into Italian and Italian editors: Alberto Diamante, Daniela Marano, Eleonora Maldina, Corrado Paina, Tiziana Tedesco, Giorgio Tinelli Photographs: Rick O’Brien Graphic Design: Denis De Klerck Printed by United Graphics Idea, managing and supervision: Corrado Paina Mansfield Press Inc. 25 Mansfield Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6J 2A9 Publisher: Denis De Klerck www.mansfieldpress.net This book is Dedicated to the Late Ron Farano Co-Founder of the Italian Chamber of Commerce of Ontario Table of Contents LETTER / LETTERA George Visintin, Corrado Paina / 7 PREFACE / PREFAZIONE -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2015 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <3 <3 <3 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 5 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 3 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 19 4 4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 8 <3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10019 Dunstable College LU5 4HG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 6 <3 <3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 6 3 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 19 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 9 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 10 5 4 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 12 5 5 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 -

Welcome to Ferrara

Welcome to Ferrara Version 2.0 – 24 April 2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EMERGENCY PHONE NUMBERS .................................................................................................................... 4 COUNTRY CODE ................................................................................................................................................ 4 INFORMATION ON HOW TO USE THE PHONE .......................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 5 ITALY ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 EMILIA ROMAGNA .............................................................................................................................................. 6 POGGIO RENATICO ............................................................................................................................................ 6 FERRARA .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 SHOPPING .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 CENTRO COMMERCIALES .................................................................................................................................. -

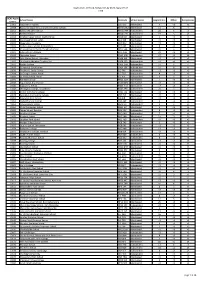

Dodea 1999 Report

Post-secondary Plans and Financial Aid 1999 Graduates Research and Evaluation Branch October 1999 Post-secondary Plans and Financial Aid 1999 Graduates Prepared by Kristin K. Medhurst Research and Evaluation Branch Department of Defense Education Activity October 1999 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures...........................................................................................................ii Plans After Graduation ............................................................................................................... 1 National Merit Scholars.............................................................................................................. 5 Scholarships and Financial Aid................................................................................................... 5 Colleges and Universities ......................................................................................................... 11 Limitations of the Study............................................................................................................ 19 Summary.................................................................................................................................. 19 Bibliography............................................................................................................................. 21 Appendix A .............................................................................................................................. 23 Appendix B ............................................................................................................................. -

Agents Workshop Tours 2017

WEBA - AGENTS HANDBOOK AGENTS HANDBOOK International Agents Workshops Agents Workshop Tours 2017 s Tours 2016 Agents (Organization in Charge for the recuritment of students) Phone : +41 79 730 34 73 E-mail : [email protected] www.webaworld.com WEBA World Annual Workshops and Fairs give you the opportunity to meet with top quality recruitments agents from all over the world or to meet and recruit directly students internationally. Welcome to the WEBA Agents Workshops Handbook attending upcoming events as well as useful articles on education abroad. For more information on our tours and how to register for our events please visit www.webaworld.com . institutions on our tour and are able to reap the rewards from the The guide will provide you with information on participating schools and details of our events. We hope to see you soon and wish you every success. Richard Affolter Owner and Executive Director of WEBA Contents Agents Workshops Dates and Location ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 03 Wellington High School - New Zealand .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 41 Merit Academy: Education for Excellence -USA ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 05 College Platon - North America ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 43 SHML, Hotel School Management School -Switzerland ... ... ... ... 05 Eastern Institute of Technology - New Zealand . ... ... ... ... ... ... 45 European School of Economics - Italy ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. 07 Oxford International Study Centre - UK ... ... ... ... ... .. -

Canadian College Italy

Canadian College Italy OUR MISSION STATEMENT To provide a unique environment in which students experience a renaissance: academically, socially and culturally. WELCOME Canadian College Italy is Canada's first high school in Italy. CCI is a co- educational boarding school that offers an academically rigorous curriculum in a semester format. Founded in 1995, we have provided a unique high quality English-language based educational experience that prepares students for success in their university studies. CCI graduates have accepted offers and received scholarships from a variety of universities throughout Canada, the U.S.A., the U.K., Australia and Europe. CCI is inspected by the Ministry of Education for the Province of Ontario, Canada, whose requirements parallel or exceed most other North American jurisdictions. EDUCATION IN AN ANCIENT CITY The essence of CCI is that challenging learning takes place in the country of the Renaissance whose archaeological, historical and art treasures are visited as a formally instructed integral part of the CCI educational experience. Classroom and book learning, upon which the School places the highest value, is dramatically enhanced when students are learning in the very places where the events being studied occurred. CCI students walk in the same streets, fields, and buildings as did the pre-Etruscans; Pompeiians and Romans; emperors and popes; artists like Raphael, da Vinci and Michelangelo. They witness first-hand at the school's Remembrance Day ceremonies, the sacrifice made by many in WWII. The Town of Lanciano, where CCI is located, is an ancient-yet-modern, safe, well serviced small city of 45,000 in the eastern Abruzzo Region. -

Blumbergs' List of Canada Corporations Act Non-Profits That

www.canadiancharitylaw.ca Blumbergs’ List of Canada Corporations Act non-profits that may need to continue to the CNCA By Mark Blumberg (April 28, 2014) The federal government as part of its Open Data initiative provides a complete list of Federal corporations (for-profit and non-profit) in XML format. We thought it might be helpful to look at which Canadian non-profits corporations are still under the old Canada Corporations Act (CCA) and may need to continue under the Canada Not-for profit Corporations Act (CNCA). Background The CNCA was brought into force in 2011 and will replace the Canada Corporations Act (CCA). The CNCA will be of particular interest to Canadian non-profit organization and charities that are incorporated federally under the CCA as they will have to file documents to continue under the CNCA or face dissolution. CCA corporations have until October 17, 2014 to complete the continuance. While the implementation of the CNCA provides a good opportunity for Federal non-profit corporations to assess their governance practices and make improvements, the failure to act may have dire consequences for some organizations. www.canadiancharitylaw.ca A few points to note about the list: 1) Many of these corporations were created a long time ago and have been dormant for many years. For many of them, mandatory dissolution will not have any negative impact and they may actually welcome the closure that dissolution provides. 2) The list contains all names (English, French and Old/New) of corporations. Therefore, although there are 34,000 names there are in fact less actual corporations. -

This Marks the Connection of British Columbia's Section of the Great

The Great Trail in British Columbia Le Grand Sentier au Colombie-Britannique This marks the connection of British Columbia’s section of The Great Trail of Canada in honour of Canada’s 150th Ceci marque le raccordement du Grand Sentier à travers Colombie-Britannique du Grand Sentier pour le 150e anniversary of Confederation in 2017. anniversaire de la Confédération canadienne en 2017. À partir d’où vous êtes, vous pouvez entreprendre l’un des voyages les plus beaux et les plus diversifiés du monde. From where you are standing, you can embark upon one of the most magnificent and diverse journeys in the world. Que vous vous dirigiez vers l’est, l’ouest, le nord ou le sud, Le Grand Sentier du Canada — créé par le sentier Whether heading east, west, north or south, The Great Trail—created by Trans Canada Trail (TCT) and its partners— Transcanadien (STC) et ses partenaires — vous offre ses multiples beautés naturelles ainsi que la riche histoire et offers all the natural beauty, rich history and enduring spirit of our land and its peoples. l’esprit qui perdure de notre pays et des gens qui l’habitent. Launched in 1992, just after Canada’s 125th anniversary of Confederation The Great Trail was conceived by a group of Lancé en 1992, juste après le 125e anniversaire de la Confédération du Canada, Le Grand Sentier a été conçu, par un visionary and patriotic individuals as a means to connect Canadians from coast to coast to coast. groupe de visionnaires et de patriotes, comme le moyen de relier les Canadiens d’un océan aux deux autres.