Casanare's Struggle to Win Freedom from Boyacá During

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meta River Report Card

Meta River 2016 Report Card c Casanare b Lower Meta Tame CASANARE RIVER Cravo Norte Hato Corozal Puerto Carreño d+ Upper Meta Paz de Ariporo Pore La Primavera Yopal Aguazul c Middle Meta Garagoa Maní META RIVER Villanueva Villavicencio Puerto Gaitán c+ Meta Manacacías Puerto López MANACACÍAS RIVER Human nutrition Mining in sensitive ecosystems Characteristics of the MAN & AG LE GOV E P RE ER M O TU N E E L A N P U N RI C T Meta River Basin C TA V / E ER E M B Water The Meta River originates in the Andes and is the largest I O quality index sub-basin of the Colombian portion of the Orinoco River D I R V E (1,250 km long and 10,673,344 ha in area). Due to its size E B C T R A H A Risks to S S T and varied land-uses, the Meta sub-basin has been split I I L W T N HEA water into five reporting regions for this assessment, the Upper River Y quality EC S dolphins & OSY TEM L S S Water supply Meta, Meta Manacacías, Middle Meta, Casanare and Lower ANDSCAPE Meta. The basin includes many ecosystem types such as & demand Ecosystem the Páramo, Andean forests, flooded savannas, and flooded Fire frequency services forests. Main threats to the sub-basin are from livestock expansion, pollution by urban areas and by the oil and gas Natural industry, natural habitat loss by mining and agro-industry, and land cover Terrestrial growing conflict between different sectors for water supply. -

BPXC's Operations in Casanare, Colombia

Paper Number 31 July 1999 BPXCs Operations in Casanare, Colombia: Factoring social concerns into development decisionmaking Aidan Davy Kathryn McPhail Favian Sandoval Moreno Social Development Papers Paper Number 31 July 1999 BPXCs Operations in Casanare, Colombia: Factoring social concerns into development decisionmaking Aidan Davy Kathryn McPhail Favian Sandoval Moreno This publication was developed and produced by the Social Development Family of the World Bank. The Environment, Rural Development, and Social Development Families are part of the Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (ESSD) Network. The Social Development Family is made up of World Bank staff working on social issues. Papers in the Social Development series are not formal publications of the World Bank. They are published informally and circulated to encourage discussion and comment within the development community. The findings, interpretations, judgments, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and should not be attributed to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive Directors or the governments they represent. Copies of this paper are available from: Social Development The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 USA Fax: 202-522-3247 E-mail: [email protected] Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 7 Aims and Objectives 7 Approach 8 Project Location 8 Main Issues to Factor into the Evaluation 9 Route Map to the Report 9 2. An Evolving Social and Environmental Context 11 Description of BPXCs Operations 11 The Environmental Context of BPXCs Operations 13 The Social Context of BPXCs Operations 13 Key Stakeholders and Their Interactions 13 The Evolving Demographic and Socioeconomic Context 16 Conflict in Casanare 19 3. -

From an Autonomous Province to a Habsburg Principality

FROM AN AUTONOMOUS PROVINCE TO A HABSBURG PRINCIPALITY. THE LEGISLATIVE ROLE OF THE TRANSYLVANIAN DIET DURING THE 18TH CENTURY Gelu Fodor* Keywords: Werböczy, Tripartitum, constitution, Diet, Pragmatic Sanction, legislative system Cuvinte cheie: Werböczy, Tripartitum, constituţie, dietă, Pragmatica Sancţiune, sistem legislativ Introductory considerations Our approach aims to shed light on the evolution of the Transylvanian constitution and constitutionalism after the incorporation of the Principality of Transylvania within the administrative structures of the Habsburg Empire, the upper chronological limit being the provisions the Diet issued in 1791. In order to achieve this goal, we intend to examine all the aspects that contributed decisively to shaping the constitutional realities in the Principality, focusing in particular on the institutional and legislative role of the Diet, as a representative authority for the nobility in its relationship with the Habsburg sovereigns. The conquest of Transylvania by the Habsburgs gradually brought about major changes as regards the law-making institutions, and some of these changes were made with the direct involvement of the Diet. The central aspect on which we shall dwell and which, in our opinion, was the quintessence of the entire legislative process unfolding throughout the 18th century, revolved around the articles of law enacted by the Diet of 1744 and, respectively, of the Diet of 1791. By analysing their specific provisions, we shall attempt to highlight the changes that took place in the constitutional structure of the Principality up until the turn of the 19th century. Another point of interest for our study revolves around what certain historians regard as the very foundation of the Transylvanian political system, namely the Constitutions of Transylvania: Werböczy’s Tripartitum, Aprobatae Constitutiones and Compilatae Constitutiones. -

El Libro La Violencia En Colombia (1962 - 1964)

El libro La Violencia en Colombia (1962 - 1964). Radiografía emblemática de una época tristemente célebre* The Book La Violencia en Colombia (1962 – 1964). An Emblematic Analysis of a Sadly Famous Period [35] Resumen jefferson jaramillo marín** Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia Dos acontecimientos históricos marcaron los inicios del Frente Nacional en Co- lombia. El primero de ellos sucedió en mayo de 1958 cuando el gobierno de transición, liderado por una Junta Militar, creó la Comisión Nacional Investigadora de las Causas y Situaciones Presentes de la Violencia en el Territorio Nacional. El segundo coincidió con la publicación en julio de 1962 del primer tomo del libro La Violencia en Colombia. Mientras el objetivo de la Comisión fue básicamente servir de espacio institucional para tramitar las secuelas de la denominada Violencia, el objetivo del libro fue servir de plata- forma académica y expresión de denuncia para revelar etnográfica y sociológicamente sus manifestaciones en las regiones. A partir de un acopio de material de archivo de prensa de la época y entrevistas a expertos, este artículo sostiene que, en su momento, fue la Comisión la que no logró su objetivo, dado el carácter pactista que tuvo esta iniciativa. Sin embargo, las metas propuestas fueron alcanzadas cuatro años después con la publicación del libro. Es decir, que aquella radiografía regional de las secuelas del desangre que la Co- misión logró parcialmente sería luego profundizada radicalmente por un libro que pronto devendría en la memoria emblemática de la época. Palabras clave: Colombia, Comisión de 1958, Frente Nacional, La Violencia. * Conferencia ofrecida en el marco del panel “El libro La Violencia en Colombia: 50 años de una radiografía emblemática y fundacional” realizado el 8 de octubre de 2012 en la Ponti- ficia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá. -

ESTMA Identification Number E798884 Amended Report

Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report Reporting Entity Name Parex Resources Inc. Reporting Year From 2020-01-01 To: 2020-12-31 Date submitted 2021-05-26 Original Submission Reporting Entity ESTMA Identification Number E798884 Amended Report Other Subsidiaries Included (optional field) Not Consolidated Not Substituted Attestation Through Independent Audit In accordance with the requirements of the ESTMA, and in particular section 9 thereof, I attest that I engaged an independent auditor to undertake an audit of the ESTMA report for the entity(ies) and reporting year listed above. Such an audit was conducted in accordance with the Technical Reporting Specifications issued by Natural Resources Canada for independent attestation of ESTMA reports. The auditor expressed an unmodified opinion, dated YYYY-MM-DD, on the ESTMA Report for the entity(ies) and period listed above. The independent auditor's report can be found at Calgary. Full Name of Director or Officer of Reporting Entity Kenneth G. Pinsky Date 2021-05-26 Position Title Chief Financial Officer Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report Reporting Year From: 2020-01-01 To: 2020-12-31 Reporting Entity Name Parex Resources Inc. Currency of the Report USD Reporting Entity ESTMA Identification E798884 Number Subsidiary Reporting Entities (if necessary) Payments by Payee Departments, Agency, etc… Infrastructure Total Amount paid to Country Payee Name within Payee that Received Taxes Royalties Fees Production Entitlements Bonuses Dividends Notes Improvement -

Construcción De Una Línea Base Para La Medición Del Impacto De La Educación Superior Rural En La Colombia Profunda

Revista de la Universidad de La Salle Volume 2014 Number 64 Article 8 January 2014 Construcción de una línea base para la medición del impacto de la educación superior rural en la Colombia profunda Miguel Darío Sosa Rico Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, [email protected] Luis Alejandro Taborda Andrade Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/ruls Citación recomendada Sosa Rico, M. D., y L.A. Taborda Andrade (2014). Construcción de una línea base para la medición del impacto de la educación superior rural en la Colombia profunda. Revista de la Universidad de La Salle, (64), 155-173. This Artículo de Revista is brought to you for free and open access by the Revistas de divulgación at Ciencia Unisalle. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revista de la Universidad de La Salle by an authorized editor of Ciencia Unisalle. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Construcción de una línea base para la medición del impacto de la educación superior rural en la Colombia profunda Miguel Darío Sosa Rico* Luis Alejandro Taborda Andrade** Resumen Utopía es un Programa de la Universidad de La Salle que genera opor- tunidades de educación para los jóvenes de los sectores rurales de Colombia. El presente documento tiene como objetivo hacer una des- cripción general de las dinámicas económicas de las zonas de origen de los estudiantes del Programa, con el fin de hacer una primera aproxima- ción a la línea base para la construcción de la metodología de medición de su impacto. -

List of Subjects, Admission of New Subjects Article 66

Chapter 3. Federative Arrangement (Articles 65–79) 457 Chapter 3. Federative Arrangement See also Art.5 Federative arrangement Article 65: List of subjects, admission of new subjects Art.65.1. The composition of the RF comprises the following RF subjects: the Republic Adygeia (Adygeia), the Republic Altai, the Republic Bashkortostan, the Republic Buriatia, the Republic Dagestan, the Republic Ingushetia, the Kabarda-Balkar Republic, the Republic Kalmykia, the Karachai-Cherkess Republic, the Republic Karelia, the Republic Komi, the Republic Mari El, the Republic Mordovia, the Republic Sakha (Iakutia), the Republic North Ossetia- Alania, the Republic Tatarstan (Tatarstan), the Republic Tyva, the Udmurt Republic, the Republic Khakasia, the Chechen Republic, and the Chuvash Republic-Chuvashia; Altai Territory, Krasnodar Territory, Krasnoiarsk Territory, Primor’e Territory, Stavropol’ Territory, and Khabarovsk Territory; Amur Province, Arkhangel’sk Province, Astrakhan’ Province, Belgorod Province, Briansk Province, Vladimir Province, Volgograd Province, Vologda Province, Voronezh Province, Ivanovo Province, Irkutsk Province, Kaliningrad Province, Kaluga Province, Kamchatka Province, Kemerovo Province, Kirov Province, Kostroma Province, Kurgan Province, Kursk Province, Leningrad Province, Lipetsk Province, Magadan Province, Moscow Province, Murmansk Province, Nizhnii Novgorod Province, Novgorod Province, Novosibirsk Province, Omsk Province, Orenburg Province, Orel Province, Penza Province, Perm’ Province, Pskov Province, Rostov Province, Riazan’ -

Presentación De Powerpoint

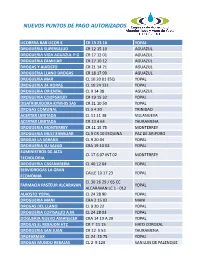

NUEVOS PUNTOS DE PAGO AUTORIZADOS LICORERA BAR LICOR S CR 19 23 10 YOPAL DROGUERIA SUPERSALUD CR 12 15 10 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA VIDA AGUAZUL P G CR 17 12 01 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA FAMILIAR CR 17 10 12 AGUAZUL DROGAS Y ALKOSTO CR 21 14 71 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA LLANO DROGAS CR 18 17 99 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA MAR CL 10 20 01 ESQ YOPAL DROGUERIA 24 HORAS CL 10 24 131 YOPAL DROGUERIA ORIENTAL CL 9 14 38 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA COOPSALUD CR 19 15 32 YOPAL DISATRIBUIDORA KYWHIS SAS CR 21 10 50 YOPAL DROGAS COMUNAL CL 5 4 20 TRINIDAD ACERTAR LIMITADA CL 11 11 38 VILLANUEVA ACERTAR LIMITADA CR 13 4 64 TAURAMENA DROGUERIA MONTERREY CR 11 15 75 MONTERREY DROGUERIA MULTIFAMILIAR CL 9 CR 10 ESQUINA PAZ DE ARIPORO DROGAS LA SABANA CL 9 20 04 YOPAL DROGUERIA SU SALUD CRA 19 10 02 YOPAL SUMINISTROS DE ALTA CL 17 6 07 INT 02 MONTERREY TECNOLOGIA DROGUERIA CASANAREÑA CL 40 12 04 YOPAL SERVIDROGAS LA GRAN CALLE 10 17 23 YOPAL ECONOMIA CL 30 26 29 / 65 CC FARMACIA PASTEUR ALCARAVAN YOPAL ALCARAVAN LC 1 - 012 ALKOSTO YOPAL CL 24 28 90 YOPAL DROGUERIA MANI CRA 2 15 02 MANI DROGAS DEL LLANO CL 9 20 22 YOPAL DROGUERIA COPISALUD A.M. CL 24 28 03 YOPAL DOGUERIA NUEVO AMANECER CRA 14 19 A 20 YOPAL DROGAS EL REBAJON HTZ CR 7 11 15 HATO COROZAL DROGUERIA SAN JUAN CR 12 5 53 TAURAMENA DROFARMAX CL 24 25 75 YOPAL DROGAS MUNDO REBAJAS CL 2 9 123 SAN LUIS DE PALENQUE NUEVOS PUNTOS DE PAGO AUTORIZADOS DROGUERIA ANFREX SALUD CL 16 21 05 YOPAL DROGUERIA COLFAM CL 15 17 67 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA SU SALUD 2 CL 9 16 29 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA SAN JUAN CARRERA 16 # 36B-26 YOPAL CASANARE BRR EL PORTAL DROGUERIA -

Missing People in Casanare

Missing People in Casanare Daniel Guzmán, Tamy Guberek, Amelia Hoover, and Patrick Ball November 28, 2007 1 Introduction How many people are missing in the department of Casanare, Colombia? This apparently simple question proves complex when we ask how many missing persons were not reported to any organization, and becomes even more difficult in the context of politically contentious debates about exhumation, identification and reunification of remains. How can we be sure that all the missing are accounted for in some way? How should we approach the problem of searching for victims? Answers to these and other questions will be incorrect if we assume that any list or combination of lists is “comprehensive.” Ultimately, correct answers rely on scientific estimation of the number of missing persons. In this initial analysis, we estimate that the total number of missing persons in Casanare 1986-2007 is 2,553.1 Approximately 1,500 persons were reported missing during this period, yielding an “undocumented rate” of about 40% (of total estimated missing persons). We emphasize that the rate of undocumented missing persons found in Casanare does not necessarily represent the rate that could be found in Colombia more generally, if data were available. We recom- mend that additional data should be gathered and made available for analysis by statisticians and social scientists. Furthermore, this analysis demonstrates that no single list of missing persons estimates the total number of persons likely to be missing in Casanare. We proceed in several sections. First, we outline our findings. Then we con- sider the available data on Casanare from thirteen data collection projects. -

Transformaciones Económicas Y Sociales En Las Juntas De

TRANSFORMACIONES ECONÓMICAS Y SOCIALES EN LAS JUNTAS DE ACCIÓN COMUNAL A CAUSA DE LA INDUSTRIA PETROLERA EL CASO DE LA VEREDA EL BANCO BUENOS AIRES, HATOCOROZAL, CASANARE Anderson Zamir Rojas Cortázar Directora Olga Lucía Castillo Ospina Maestría Desarrollo Rural Facultad de Estudios Ambientales y Rurales Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Octubre 31 de 2017 Bogotá, Colombia Tabla de Contenidos Capítulo Uno - Introducción y Planteamiento del Problema .............................. 5 1.1 Problema de Investigación .................................................................. 7 1.2 Aspectos metodológicos .................................................................... 12 Capítulo Dos - Algunas características de la Zona de Estudio .......................... 16 2.1 Breve historia territorial y poblacional del municipio .............................. 16 2.2 La Junta de Acción Comunal (JAC) de la vereda El Banco de Buenos Aires 18 2.3 Acceso a servicios públicos ................................................................ 19 2.4 Estructura ecológica ......................................................................... 21 Capítulo Tres - La industria petrolera en el Departamento del Casanare ........... 23 3.1 Los inicios de la explotación petrolera en el Casanare ............................ 23 3.2 La reforma del sistema de regalías y la corrupción ................................ 25 3.3 La relación de la industria petrolera con el conflicto armado ................... 31 Capítulo Cuatro - Estado del Arte ............................................................... -

190205 USAID Colombia Brief Final to Joslin

COUNTRY BRIEF I. FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS II.COLOMBIA III. OVERVIEW Colombia experiences very high climate exposure concentrated in small portions of the country and high fragility stemming largely from persistent insecurity related to both longstanding and new sources of violence. Colombia’s effective political institutions, well- developed social service delivery systems and strong regulatory foundation for economic policy position the state to continue making important progress. Yet, at present, high climate risks in pockets across the country and government mismanagement of those risks have converged to increase Colombians’ vulnerability to humanitarian emergencies. Despite the state’s commitment to address climate risks, the country’s historically high level of violence has strained state capacity to manage those risks, while also contributing directly to people’s vulnerability to climate risks where people displaced by conflict have resettled in high-exposure areas. This is seen in high-exposure rural areas like Mocoa where the population’s vulnerability to local flooding risks is increased by the influx of displaced Colombians, lack of government regulation to prevent settlement in flood-prone areas and deforestation that has Source: USAID Colombia removed natural barriers to flash flooding and mudslides. This is also seen in high-exposure urban areas like Barranquilla, where substantial risks from storm surge and riverine flooding are made worse by limited government planning and responses to address these risks, resulting in extensive economic losses and infrastructure damage each year due to fairly predictable climate risks. This brief summarizes findings from a broader USAID case study of fragility and climate risks in Colombia (Moran et al. -

Colegios Del Departamento De Casanare

Colegios del departamento de Casanare NO. departamento 1 Casanare 2 Casanare 3 Casanare 4 Casanare 5 Casanare 6 Casanare 7 Casanare 8 Casanare 9 Casanare 10 Casanare 11 Casanare 12 Casanare 13 Casanare 14 Casanare 15 Casanare 16 Casanare 17 Casanare 18 Casanare 19 Casanare Page 1 of 16 09/28/2021 Colegios del departamento de Casanare Municipio COD DANE AGUAZUL 185010000271 AGUAZUL 285010000259 AGUAZUL 285010000640 AGUAZUL 285010000364 AGUAZUL 185010000629 AGUAZUL 185010000505 AGUAZUL 285010000038 CHAMEZA 185015000104 HATO COROZAL 185125000959 HATO COROZAL 285125001429 HATO COROZAL 285125001666 HATO COROZAL 285125000279 HATO COROZAL 285125000597 HATO COROZAL 285125000562 HATO COROZAL 285125000058 HATO COROZAL 185125000029 HATO COROZAL 285125001470 HATO COROZAL 285125000422 LA SALINA 185136000047 Page 2 of 16 09/28/2021 Colegios del departamento de Casanare NOMBRE IE O CE ZONA CARÁCTER Ie camilo torres restrepo Urbana Academico - tecnico Ie cupiagua Rural Academico Ie leon de greiff Rural Tecnico Ie luis maria jimenez Rural Tecnico Ie jorge eliecer gaitan Urbana Academico Ie san agustin Urbana Academico Ie la turua Rural Academico Ie jose antonio galan Urbana Tecnico Ie antonio martinez delgado Urbana Tecnico Ie bonifacio gutierrez Rural Academico Ie indigena alegaxu Rural Academico Ie carlos lleras restrepo Rural No aplica Ie indigena lisa maneni Rural Academico Ie murewom wayuri Rural Academico Ie horacio perdomo Rural Academico Ie luis hernandez vargas Urbana Tecnico Ie puerto colombia Rural Academico Ie simon bolivar (el chire) Rural