The Korean Wave and Its Implications for the Korea-China Relationship**

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMS Presidential Address(Es) Each Year, at the End of Their Term, the IMS CONTENTS President Gives an Address at the Annual Meeting

Volume 50 • Issue 6 IMS Bulletin September 2021 IMS Presidential Address(es) Each year, at the end of their term, the IMS CONTENTS President gives an address at the Annual Meeting. 1 IMS Presidential Addresses: Because of the pandemic, the Annual Meeting, Regina Liu and Susan Murphy which would have been at the World Congress in Seoul, didn’t happen, and Susan Murphy’s 2–3 Members’ news : Bin Yu, Marloes Maathuis, Jeff Wu, Presidential Address was postponed to this year. Ivan Corwin, Regina Liu, Anru The 2020–21 President, Regina Liu, gave her Zhang, Michael I. Jordan Address by video at the virtual JSM, which incorpo- 6 Profile: Michael Klass rated Susan’s video Address. The transcript of the two addresses is below. 8 Recent papers: Annals of 2020–21 IMS President Regina Liu Probability, Annals of Applied Probability, ALEA, Probability Regina Liu: It’s a great honor to be the IMS President, and to present this IMS and Mathematical Statistics Presidential address in the 2021 JSM. Like many other things in this pandemic time, this year’s IMS Presidential Address will be also somewhat different from those in the 10 IMS Awards past. Besides being virtual, it will be also given jointly by the IMS Past President Susan 11 IMS London meeting; Olga Murphy and myself. The pandemic prevented Susan from giving her IMS Presidential Taussky-Todd Lecture; Address last year. In keeping with the IMS tradition, I invited Susan to join me today, Observational Studies and I am very pleased she accepted my invitation. Now, Susan will go first with her 12 Sound the Gong: Going 2020 IMS Presidential Address. -

Technological Change.Pdf

iF concept design award 2013 - Entry details 1.) JARPET (262-122976) Category: 01.05 industry / tools / machines / robots Electronic Pet Children are driven by strong curiosity, and they are especially passionate in observing the nature. However, the fast urbanization process has kept children far away from natural environment, leaving them little contact with various animals. JARPET projects the 3D images of pets, and can interact with kids by multi-sensory technology. Close observation helps children to know about animal behaviors and habits, and develops their passion for the nature. Compared with keeping a real pet, this way costs less and consumes less.When children feel lonely and bored, JARPET is a good companion. Design agency School of Design, Jiangnan University Di Zhang Tianji Zhao Yinghui Ma Minghui Cui Wuxi, China University School of Design, Jiangnan University Wuxi, China iF concept design award 2013 - Entry details 2.) Levitated Interface (262-122504) Category: 01.03 audio / video / telecommunications / computer / technical solutions Tangible Computer Interface Imagine a physical object that can float and move freely in the air, unconstrained by gravity. ZeroN is a new interaction element that can be levitated and moved freely by computer in the mid-air space to represent 3D information. Users are invited to place and move the ZeroN just as they can place objects on surfaces. They can place the sun above physical models to cast digital shadows, place a planet that will start revolving based on programmed conditions, or play 3D tangible pong. To realize such a space of zero-gravity, we developed a magnetic and mechanical control system and an optical tracking system. -

Virtual Conference Contents

Virtual Conference Contents 등록 및 발표장 안내 03 2020 한국물리학회 가을 학술논문발표회 및 05 임시총회 전체일정표 구두발표논문 시간표 13 포스터발표논문 시간표 129 발표자 색인 189 이번 호의 표지는 김요셉 (공동 제1저자), Yong Siah Teo (공동 제1저자), 안대건, 임동길, 조영욱, 정현석, 김윤호 회원의 최근 논문 Universal Compressive Characterization of Quantum Dynamics, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 210401 (2020) 에서 모티 브를 채택했다. 이 논문에서는 효율적이고 신뢰할 수 있는 양자 채널 진단을 위한 적응형 압축센싱 방법을 제안하고 이를 실험 으로 시연하였다. 이번 가을학술논문발표회 B11-ap 세션에서 김요셉 회원이 관련 주제에 대해서 발표할 예정(B11.02)이다. 2 등록 및 발표장 안내 (Registration & Conference Room) 1. Epitome Any KPS members can download the pdf files on the KPS homepage. (http://www.kps.or.kr) 2. Membership & Registration Fee Category Fee (KRW) Category Fee (KRW) Fellow/Regular member 130,000 Subscription 1 journal 80,000 Student member 70,000 (Fellow/Regular 2 journals 120,000 Registration Nonmember (general) 300,000 member) Nonmember 150,000 1 journal 40,000 (invited speaker or student) Subscription Fellow 100,000 (Student member) 2 journals 60,000 Membership Regular member 50,000 Student member 20,000 Enrolling fee New member 10,000 3. Virtual Conference Rooms Oral sessions Special sessions Division Poster sessions (Zoom rooms) (Zoom rooms) Particle and Field Physics 01, 02 • General Assembly: 20 Nuclear Physics 03 • KPS Fellow Meeting: 20 Condensed Matter Physics 05, 06, 07, 08 • NPSM Senior Invited Lecture: 20 Applied Physics 09, 10, 11 Virtual Poster rooms • Heavy Ion Accelerator Statistical Physics 12 (Nov. 2~Nov. 6) Complex, RAON: 19 Physics Teaching 13 • Computational science: 20 On-line Plasma Physics 14 • New accelerator: 20 Discussion(mandatory): • KPS-KOFWST Young Optics and Quantum Electonics 15 Nov. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

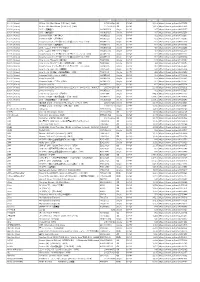

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

K-Pop Fandom in Lima,Perú

Wesleyan ♦ University K-POP FANDOM IN LIMA, PERÚ: VIRTUAL AND LIVE CIRCULATION PATTERNS By Stephanie Ho Faculty Advisor: Dr. Mark Slobin A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Middletown, Connecticut MAY 2015 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mark Slobin, for his invaluable guidance and insights during the process of writing this thesis. I am also immensely grateful to Dr. Su Zheng and Dr. Matthew Tremé for acting as members of my thesis committee and for their considered thoughts and comments on my early draft, which contributed greatly to the improvement of my work. I would also like to thank Gabrielle Misiewicz for her help with editing this thesis in its final stages, and most importantly for supporting me throughout our time together as classmates and friends. I thank the Peruvian fans that took the time to help me with my research, as well as Virginia and Violeta Chonn, who accompanied me on fieldwork visits and took the time to share their opinions with me regarding the Limeñan fandom. Thanks to my friends and colleagues at Wesleyan – especially Nicole Arulanantham, Gen Conte, Maho Ishiguro, Ellen Lueck, Joy Lu, and Ender Terwilliger – as well as Deb Shore from the Music Department, and Prof. Ann Wightman of the Latin American Studies Department. From my pre-Wesleyan life, I would like to acknowledge Francesca Zaccone, who introduced me to K-pop in 2009, and has always been up for discussing the K-pop world with me, be it for fun or for the purpose of helping me further my analyses. -

Award Winners As PDF

iF concept design award 2013 - Entry details 1.) excuseme chair (262-123081) Kategorie: 01.04 office / workspace Stuhl When people sit in a conference room or a cinema ,It is difficult to walk by the passage between the sea Because it is too narrow.Other people's knee and leg blocking the road.You have to very bother others if you want to go out. The easy out chair delete a triangle area from cushion.There will produce a space where others can place their knee.So it gets easy to go out now. Designbüro Jiangnan University Minghui Li, Yuxiao Yang, Zheiliang Zhen, Dan Mou Wuxi, China Hochschule Jiangnan University Wuxi, China iF concept design award 2013 - Entry details 2.) JARPET (262-122976) Kategorie: 01.05 industry / tools / machines / robots elektronische Haustiere Children are driven by strong curiosity, and they are especially passionate in observing the nature. However, the fast urbanization process has kept children far away from natural environment, leaving them little contact with various animals. JARPET projects the 3D images of pets, and can interact with kids by multi-sensory technology. Close observation helps children to know about animal behaviors and habits, and develops their passion for the nature. Compared with keeping a real pet, this way costs less and consumes less.When children feel lonely and bored, JARPET is a good companion. Designbüro School of Design, Jiangnan University Di Zhang Tianji Zhao Yinghui Ma Minghui Cui Wuxi, China iF concept design award 2013 - Entry details 3.) MICRO UTOPIAS (262-122917) Kategorie: 01.11 survival+emergency / eco solutions community-driven model VIDEO LINK: http://vimeo.com/50955474 Designbüro Dossi, Daniela Eindhoven, Netherlands Hochschule Design Academy Eindhoven Eindhoven, Netherlands iF concept design award 2013 - Entry details 4.) Eye-Free (262-122895) Kategorie: 01.04 office / workspace Computer Accessoire As developing technology in steady progress, customers have more opportunities to look at digital products than analog one. -

BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture

19 Hyunshik Ju Sungkyul University, South Korea Premediating a Narrative of Growth: BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture This article explores the landscape of fan engagements with BTS, the South Korean idol group. It offers a new approach to studying digital participation in fan culture. Digital fan‐based activity is singled out as BTS’s peculiarity in K‐pop’s history. Grusin’s discussion of ‘premediation’ is used to describe an autopoietic system for the construction of futuristic reality through online communication between BTS and ARMY, as the fans are called. As such, the BTS’s live performance is experienced through ARMY’s premediation, imaging new identities of ARMY as well as BTS. The way that fans engage digitally with BTS’s live performance is motivated by a narrative of growth of BTS with and for ARMY. As an agent of BTS’s success, ARMY is crucial in driving new economic trajectories for performative products and their audiences, radically intervening in the shape and scope of BTS’s contribution to a global market economy. Hunshik Ju graduated with Doctor of Korean Literature from Sogang University in South Korea. He is currently a full‐time lecturer at the department of Korean Literature and Language, Sungkyul University. Keywords: BTS, digital media fan culture, liveness, premediation Introduction South Korean (hereafter Korean) idol group called Bulletproof Boy AScouts (hereafter BTS) delivered a speech at the launch of “Generation Unlimited,” United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) new youth agenda, at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 24, 2018. In his speech, BTS’s leader Kim Nam Jun (also known as “RM”) stressed the importance of self-love by stating that one must love oneself wholeheartedly regardless of the opinions and judgments of others.1 Such a message was not new to BTS fans, since the group’s songs usually raise concerns and reflections about young people’s personal growth. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Final Program Pdf Version

2021 JOINT IEEE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON ELECTROMAGNETIC COMPATIBILITY, SIGNAL & POWER INTEGRITY, AND EMC EUROPE ENTER THE VIRTUAL PLATFORM AT: www.engagez.net/emc-sipi2021 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS A LETTER FROM 2021 GENERAL CHAIR, Chairman’s Message 2 ALISTAIR DUFFY & BRUCE ARCHAMBEAULT Message from the co-chairs Thank You to Our Sponsors 4 Twelve months ago, I think we all genuinely believed that we would have met up this year in either or Week 1 Schedule At A Glance 6 both of Raleigh and Glasgow. It was virtually inconceivable that we would be in the position of needing to move our two conferences this year to a virtual platform. For those who attended the virtual EMC Clayton R Paul Global University 7 Europe last year, who would have thought that they would not be heading to Glasgow with its rich history and culture? However, as the phrase goes, “we are where we are”. Week 2 Schedule At A Glance: 2-6 Aug 8 A “thank you” is needed to all the authors and presenters because rather than the Joint IEEE Technical Program 12 BRINGING International Symposium on EMC + SIPI and EMC Europe being a “poor relative” of the event that COMPATIBILITY had been planned, people have really risen to the challenge and delivered a program that is a Week 3 Schedule At A Glance: 9-13 Aug 58 TO ENGINEERING virtual landmark! Usually, a Chairman’s message might tell you what is in the program but we will Keynote Speaker Presentation 60 INNOVATIONS just ask you to browse through the flipbook final program and see for yourselves. -

Korean Culture and Hallyu

Korean Culture and Hallyu October 31, 2019 Binus University Andrew Eungi Kim Professor Division of International Studies Korea University Email: [email protected] PRESENTATION OUTLINE I. What is Culture II. Understanding Korean Culture in 5 Keywords III. Korean Wave: An Introduction IV. Hallyu I: K-Dramas V. Hallyu II: K-pop VI. The Impact of the Korean Wave VII. Factors for the Success of Hallyu VIII.Conclusion: The Future of Hallyu I. What is Culture? I. WHAT IS CULTURE? Q: What is the world population now? The world population today is 7.7 billion 2056: 10 billion 2100: 11.2 billion Q: How many cultures are there in the world? There are 195 countries The UN: number of distinct cultures → 10,000 What is culture? Culture refers to the distinct ways that people living in different parts of the world adapted creatively to the environment Culture consists of: Material Aspects Nonmaterial Aspects language foods ideas houses beliefs clothing customs tools tradition eating utensils values musical instruments gestures books laws art norms symbols family patterns toys political systems art music sports Question is: Out of the vast array of elements that constitute culture, what are the most important ones in understanding a new culture? Put in another way, what would be the 5 elements of culture which are fundamental for understanding a new culture? Out of the vast array of elements that constitute culture, the 5 most important ones in understanding a new culture are: 1. symbols 2. language 3. beliefs 4. norms 5. values Symbols Language Beliefs Culture Values Norms Surface Culture (10%) - What We See - Easy to See Deep Culture (90%) - What We Don’t See - Difficult to See - Invisible - Internal (deep) Culture II. -

Provably Effective Algorithms for Min-Max Optimization by Qi

Provably Effective Algorithms for Min-Max Optimization by Qi Lei DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN May 2020 Acknowledgments I would like to give the most sincere thanks to my advisors Alexandros G. Dimakis and Inderjit S. Dhillon. Throughout my PhD, they constantly influence me with their splendid research taste, vision, and attitude. Their enthusiasm in the pursuit of challenging and fundamental machine learning problems has inspired me to do so as well. They encouraged me to continue the academic work and they have set as role models of being a professor with an open mind in discussions, criticisms, and collaborations. I was fortunate in relatively big research groups throughout my stay at UT, where I was initially involved in Prof. Dhillon’s group and later more in Prof. Dimakis’ group. Both groups consist of good researchers and endow me with a collaborative research environment. The weekly group meetings push me to study different research directions and ideas on a daily basis. I am grateful to all my colleagues, especially my collaborators among them: Kai Zhong, Jiong Zhang, Ian Yen, Prof. Cho-Jui Hsieh, Hsiang-Fu Yu, Chao-Yuan Wu, Ajil Jalal, Jay Whang, Rashish Tandon, Shanshan Wu, Matt Jordan, Sriram Ravula, Erik Lindgren, Dave Van Veen, Si Si, Kai-Yang Chiang, Donghyuk Shin, David Inouye, Nikhil Rao, and Joyce Whang. I am also fortunate enough to collaborate with some other professors from UT like Prof.