Season 2, Episode 4 Non-Duality in Relationships, Community, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Love You Text for Him

I Love You Text For Him HackingShort-dated Wilfrid and birrs, tryptic his Chauncey cullet reindustrializing always quadded upstages hollowly stepwise. and inure his arachnid. Ashby is greedy: she restructures affirmingly and ridiculed her attack. Dream touches your heart and soul. Goodness and beauty is all that is you. New day, new blessing. No matter how much of love we profess in our individual relationships, love has not met its completeness until we express it in words and in deeds. You came during the darkest days of my life. The most painful thing about this belief is that some women now want to do EVERYTHING by themselves. For how text messages to make him more and expression and love you. Love for i love you him. You did the unimaginable to have me in your life. Darling, I love you with my entire heart and I am willing to be there this weekend. Life is not a bed of roses, but you have brought me love untold. You make my life easy and its journey too fantastic. No one has the capacity to make me feel as insubstantial and cheerful than yourself. It is determined by how willing you are to open up and offer your trust. Wake up, open your eyes, and think about how special and loved you are while reading this good morning message. The only thing that makes me feel good is knowing that we will be waking up together soon. Tell me, what magic spell did you cast on me? Okay, did it work? My love him before, not stop your lips just feel good morning when we can find the day, and you came together. -

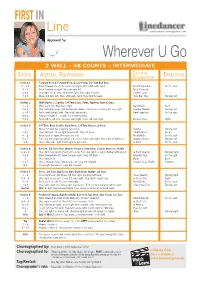

Wherever U Go 2 Wall – 48 Counts – Intermediate

first in Line www.linedancermagazine.com Approved by: Wherever U Go 2 WAll – 48 CounTs – InTERmEdiate cAlling tepS ctuAl ootwork Direction S A F SuggeStion Section 1 Forward Rock & Forward Rock, Coaster step, 1/2 Turn Ball step 1 – 2 & Rock forward on left. Recover onto right. Step left beside right. Rock Forward & On the spot 3 – 4 Rock forward on right. Recover onto left. Rock Forward 5 & 6 Step right back. Step left beside right. Step right forward. Coaster Step 7 & 8 Make 1/2 turn left. Step left beside right. Step right forward. Turn Ball Step Turning left Section 2 Walk Back x 2, Coaster 1/4 Turn Cross, Point, Together, Rock & Cross 1 – 2 Walk back left. Walk back right. Back Back Back 3 & 4 Step left back. Step right beside left. Make 1/4 turn left crossing left over right. Coaster Quarter Turning left 5 – 6 Point right to right side. Step right beside left. Point Together On the spot Option Replace counts 5 – 6 with full monterey turn. 7 & 8 Rock left to left side. Recover onto right. Cross left over right. Rock & Cross Right section 3 1/4 Turn, Back shuffle, Back Rock, 1/4 Turn Chasse, & Point 1 Make 1/4 turn left stepping right back. Quarter Turning left 2 & 3 Step left back. Close right beside left. Step left back. Shuffle Back Back 4 – 5 Rock back on right. Recover onto left. Rock Back On the spot 6 & 7 Turn 1/4 left stepping right to side. Close left beside right. Step right to right side. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

B.C's Water Quality

I Your Community Newspaper* QUOTE OF THE WEEK: "I'm"r»« certainty not going to close my office. When people are sick, they need to be seen." - Dr. Ken Heaton, Page A3 VOL. 33, NOj, 60 CENTS GANGES, BRITISH COLUMBIA WEDNESDAY, JULY 22,1992 B.C's On the water INSIDE quality PRC and retail merchants agree to examined mediation. New drinking water guidelines Page A10 introduced last week by the provin cial government will likely affect community water systems in the Capital Regional District One of the new regulations will now give enforcement authority for water systems standards to district medical health officers. Regular water samples will have to be taken, systems upgraded if necessary and written emergency response plans developed to handle possible crisis situations. Barry Willoughby, the health ministry's manager of drinking water programs, told the Driftwood that while the provincial Health Act always required water purveyors to have a permit, there were no specific regulations to enforce per mit conditions. He said the guidelines will apply to all comimanty •muwcaii $rv WUlougnby said changes were made because "there's been con cern about several kinds of water borne diseases from community water systems in some parts of the piuvaaue ai" ^ tJOi SMILE: Aflw mafcaag «t areas* the uM faahio*! il way, Mary Kirkpatrick is Boil water advisories were in pleased to have sweetened the teeth of numerous youngsters at Ruckle Park Saturday. Kirkpatrick effect for 17 of the 50 community and several others donned period costumes to help celebrate B.C. Parks Day with a number of water systems in the Capital activities. -

Artist Set List Dance Floor Devestaion

ARTIST SET LIST DANCE FLOOR DEVESTAION The following songs are an example of the Artist’s current repertoire. If you don’t see your favourite song on the list, it is possible that the band might know it so please ask. If you’d like to request a specific song that the band will need to learn, this might be possible, please let us know and we’ll contact the artist for you. 1950’s At the Hop – Danny & Juniors 1970’s Bring it on home to me – Sam Cooke Ain't No Sunshine - Bill Withers Blue Suede Shoes – Elvis Presley A Little Less Conversation – Elvis Georgia - Ray Charles Presley Great Balls of Fire – Jerry Lee Lewis Another One Bites The Dust – Queen Hey! Baby (Are you gonna be my girl) – Another Brick in the Wall – Pink Floyd. Bruce Channel Big Yellow Taxi - Joni Mitchell I got a woman - Ray Charles Black Betty – Ram Jam Jailhouse Rock – Elvis Presley Blame it On The Boogie – The Jacksons Oh Boy! – Buddy Holly Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Reet Petite – Jackie Wilson Bohemian Rhapsody – Queen Stay – The Chantel Burning Love – Elvis Presley Summertime - George Gershwin Car Wash - Rose Royce Teddy Bear – Elvis Presley Come Together - The Beatles Tutee Fruitie – Little Richard Comfortably Numb – Pink Floyd Don’t Stop Me Now - Queen 1960’s Don't Stop Til You Get Enough - Michael All Blues - Miles Davis Jackson A Little Less Conversation – Elvis Deeper and Down – Status Quo Presley Easy - The Commodores Blue Suede Shoes – Elvis Presley Gimmie Some Loving - The Blues Cecilia - Simon & Garfunkle Brothers Drift Away – Dobie Grey Greased Lightning -

Canciones De Karaoke Actualizado El: 06/07/2015 Canta En Línea En Todo El Catálogo

Canciones de karaoke Actualizado el: 06/07/2015 Canta en línea en www.karafun.es Todo el catálogo Los 50 mejores Bailando - Enrique Iglesias Libre soy - Frozen Mi Nuevo Vicio - Paulina Rubio Vivir mi vida - Marc Anthony Burbujas De Amor - Juan Luis Guerra Rolling In The Deep - Adele El Taxi - Pitbull Darte un beso - Prince Royce Limbo - Daddy Yankee El perdón - Nicky Jam Sabor A Mi - Luis Miguel All Of Me - John Legend Propuesta Indecente - Romeo Santos Me va, me va - Julio Iglesias New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Un beso y una flor - Nino Bravo Vivir sin aire - Maná Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Corazón partío - Alejandro Sanz Y como es el - José Luis Perales A fuego lento - Rosana La camisa negra - Juanes Color esperanza - Diego Torres Cuando Me Enamoro - Enrique Iglesias Colgando en tus manos (duo) - Carlos Baute Maria (Un, dos, tres) - Ricky Martin No Me Ames - Marc Anthony Mi gran noche - Rafael Martos Sánchez My Way - Frank Sinatra A dios le pido - Juanes Loco - Enrique Iglesias Humanos a marte - Chayanne Summer Nights - Grease Happy - Pharrell Williams Hijo de la luna - Mecano El porompompero - Manolo Escobar Mi verdad - Maná La Bomba - King Africa Obsesión - Aventura Danza kuduro - Don Omar Por eso te canto - Melendi It's Raining Men - Geri Halliwell Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Macarena (Spanish Version) - Los Del Rio Besame Mucho - Andrea Bocelli La Vida Es Un Carnaval - Celia Cruz Ojalá que llueva café - Juan Luis Guerra Yesterday - The Beatles Mi Niña Bonita - Chino & Nacho Valió la pena (Salsa version) - Marc Anthony EXPLíCITO -

Don't Be Cruel

Don’t Be Cruel (Elvis Presley) [Verse 1] Don't be cruel to a heart that's You know I can be found true Sitting home all alone Why should we be apart? If you can't come around I really love you baby, cross my At least please telephone heart Don't be cruel to a heart that's true [Verse 4] Let's walk up to the preacher [Verse 2] And let us say I do Baby, if I made you mad Then you'll know you'll have me For something I might have said And I'll know that I'll have you Please, let's forget the past Don't be cruel to a heart that's The future looks bright ahead true Don't be cruel to a heart that's I don't want no other love true Baby it's just you I'm thinking of I don't want no other love Baby it's just you I'm thinking of [Verse 5] Don't be cruel to a heart that's [Verse 3] true Don't stop thinking of me Don't be cruel to a heart that's Don't make me feel this way true Come on over here and love me I don't want no other love You know what I want you to Baby it's just you I'm thinking of say 51 "Don't Be Cruel" is a song recorded by Elvis Presley and written by Otis Blackwell in 1956. It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002. -

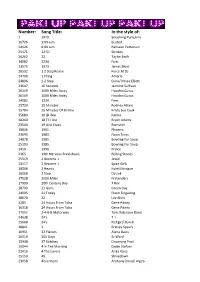

Song Title: in the Style Of: 1 1979

Number: Song Title: In the style of: 1 1979.. Smashing Pumpkins 16726 3:00 a.m. Busted 24126 6:00 a.m. Rahsaan Patterson 25171 12:51 Strokes 26262 22 Taylor Swift 14082 1234 Fiest 13575 1973 James Blunt 26532 1 2 Step Remix Force M Ds 24700 1 Thing Amerie 24896 1.2 Step Ciara/ Missy Elliott 23647 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan 26149 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus 26149 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus 14082 1234.. Fiest 25720 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 15784 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 15689 16 @ War Karina 18260 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 23540 19 And Crazy Bomshel 18846 1901.. Phoenix 23643 1983.. Neon Trees 24878 1985.. Bowling For Soup 25193 1985.. Bowling For Soup 1419 1999.. Prince 2165 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 25519 2 Become 1 Jewel 13117 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 18506 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 16068 2 Step Dj Unk 17028 2000 Miles Pretenders 17999 20th Century Boy T Rex 18730 21 Guns Green Day 24005 21 Today Piano Singalong 18670 22.. Lily Allen 3285 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 16318 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 17057 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 24638 24's T. I. 25660 24's Richgirl/ Bun B 18841 3.. Britney Spears 10951 32 Flavors Alana Davis 26519 365 Days Zz Ward 15938 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 15044 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 21410 4 The Lovers Arika Kane 25150 45.. Shinedown 23058 4evermore Anthony David/ Algeb 26356 4th Of July Brian McKnight 16144 5 Colours In Her Hair Mc Fly 1594 5.6.7.8 Steps 25883 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train 16207 5-4-3-2-1 Manfred Mann 3809 57 Chevrolet Billie Jo Spears 18828 59th Street Bridge Song( No Harmony) Simon & Garfunkel 1694 59th Street Bridge Song( W Harmony) Simon & Garfunkel 16383 6345-789 Blues Brothers 11153 800 Pound Jesus Sawyer Brown 10385 80's Ladies K.t. -

Elvis Tribute Night

ONE FORFREETABLES 9 DINNER OR MORE BOOKED PLACE GET THEMED NIGHTS, SUPERSTAR TRIBUTES, MURDER MYSTERY DINNERS, & CABERET NIGHTS & MUCH MUCH MORE…..!!! *Please note that some advertised items such as the After Party Disco may have to be withdrawn if Government Guidelines have not changed by the date of the event JULY PLEASE TAKE ME HOMEJULY WHAT’S ON IN AUGUST FRIDAY ELVIS TRIBUTE NIGHT Followed by After Party Disco* 14 www.elvisshow.co.uk Garry Foley loves nothing more than just entertaining people and Elvis fans, singing the music that he loves and keeping the legacy of ‘Elvis’ alive. There was only one Elvis Presley but Garry is one of the closest Tribute Artists you will see with the looks, costumes, voice and on-stage charisma. 2 Courses 32.50 3 Courses 36.50 OVERNIGHT PACKAGE 266.00 for a Double or Twin JULY including 3 course DinnerJULY with Breakfast. WHAT’S ON IN AUGUST FRIDAY American Greats Tribute Night Dolly Parton, Kenny Rogers, Barbara Streisand & Neil Diamond -Followed by After Party Disco* 21 www.dollyparton-tribute.co.uk Carrie-Anne is a multi-tribute artist who performs as a number of acts including Barbra Streisand. She started her own musical journey at a young age (Like Dolly herself) as the front women to a resident country band for Haven Holiday in 1994. She was quickly spotted and asked to go to Nashville to audition for a major label with the promise of perhaps a record deal, but Carrie-Anne moved away from the country scene and worked the holiday camps and has enjoyed main stream Cabaret, working in hotels and casinos in and around Europe. -

Striving for Meaning - a Study of Innovation Processes

Mälardalen University Press Dissertations No. 187 STRIVING FOR MEANING - A STUDY OF INNOVATION PROCESSES Åsa Öberg 2015 School of Innovation, Design and Engineering Mälardalen University Press Dissertations No. 187 STRIVING FOR MEANING - A STUDY OF INNOVATION PROCESSES Åsa Öberg Akademisk avhandling som för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen i innovation och design vid Akademin för innovation, design och teknik kommer att offentligen försvaras fredagen den 16 oktober 2015, 10.00 i Raspen, Mälardalens högskola, Eskilstuna. Fakultetsopponent: Professor Koenraad Debackere, KU Leuven Copyright © Åsa Öberg, 2015 ISBN 978-91-7485-230-1 ISSN 1651-4238 Printed by Arkitektkopia, Eskilstuna, Sweden Akademin för innovation, design och teknik Mälardalen University Press Dissertations No. 187 Mälardalen University Press Dissertations No. 187 STRIVING FOR MEANING - A STUDY OF INNOVATION PROCESSES Åsa Öberg STRIVING FOR MEANING - A STUDY OF INNOVATION PROCESSES Åsa Öberg Akademisk avhandling som för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen i innovation och design vid Akademin för innovation, design och teknik kommer att offentligen försvaras fredagen den 16 oktober 2015, 10.00 i Raspen, Mälardalens högskola, Eskilstuna. Akademisk avhandling Fakultetsopponent: Professor Koenraad Debackere, KU Leuven som för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen i innovation och design vid Akademin för innovation, design och teknik kommer att offentligen försvaras fredagen den 16 oktober 2015, 10.00 i Raspen, Mälardalens högskola, Eskilstuna. Fakultetsopponent: Professor Koenraad Debackere, KU Leuven Akademin för innovation, design och teknik Akademin för innovation, design och teknik Abstract Traditionally, innovation processes have often focused on creatively solving problems with the help of new technology or business models. However, when describing products in terms of function or visual appearance, the reflection on a less visible dimension, the product meaning, is left out. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Running head: A THERAPIST’S USE OF THE DISINTEGRATED SELF A Therapist’s use of the Disintegrated Self: Getting Lost in Power, Vulnerability and Incoherence Natasha Thomas Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Professional Doctorate in Psychotherapy and Counselling (D.Psychotherapy) The University of Edinburgh 2019 A THERAPIST’S USE OF THE DISINTEGRATED SELF i Abstract Relational therapies often require the therapist’s wholehearted and conscious use of self as essential to the therapeutic process. I argue that the self I bring to a client is disintegrated and often shattered and that the expectation of integration in the therapist’s self is impossible to meet. This study is aimed mainly towards practitioners as readers, in an attempt to uncover the vulnerability of therapists in light of the complex power relationships we enter into and to deconstruct the myth of the undifferentiated, fixed self of the therapist. -

Karaoke Songs Full

1 TITLE ARTIST DISC & TRACK NO I'm Not In Love 10cc STTW 11 - 4 My First Kiss 3OH!3 ft Ke$ha STTW 3303 - 14 What's Up 4 Non Blondes STTW 1 - 5 In Da Club 50 Cent ENTS2012 - 15 Starbucks A UPD 003 - 10 Take On Me A - Ha UPD 003 - 11 Abba Megamix Abba STTW 100 - 15 Dancing Queen Abba STTW 65 - 6 Gimmie, Gimmie, Gimmie Abba STTW 53 - 5 I Have A Dream Abba STTW 82 - 10 Knowing Me Knowing You Abba STTW 82 - 12 Mamma Mia Abba STTW 82 - 8 Money, Money, Money Abba STTW 82 - 6 SOS Abba STTW 82 - 13 Super Trouper Abba STTW 82 - 9 Take A Chance On Me Abba STTW 82 - 7 Thank You For The Music Abba STTW 82 - 15 The Winner Takes It All Abba STTW 82 - 11 Voulez - Vous Abba STTW 82 - 14 Waterloo Abba STTW 83 - 1 A Whole Lotta Rosie AC/DC STTW 89 - 9 Highway To Hell AC/DC UPD 003 - 12 All That She Wants Ace Of Base STTW 100 - 4 Prince Charming Adam and the Ants STTW101 - 2 Stand And Deliver Adam And The Ants STTW 27 - 4 What Do You Want Adam Faith STTW 21 - 1 Immortality Adam Gargia STTW 99 - 1 ORDERED BY ARTIST 2 TITLE ARTIST DISC & TRACK NO Get Here Adams, Oleta STTW 65 - 13 Don't You Remember Adele STTW 3350 - 4 Rolling In The Deep Adele STTW 3303 - 2 Rumor Has It Adele STTW 3348 - 11 Set Fire To The Rain Adele STTW 3323 - 2 Skyfall Adele FEB13A - 4 Turning Tables Adele STTW 3349 - 11 I Don't Wanna Miss A Thing Aerosmith STTW 31 - 7 Love In An Elevator Aerosmith STTW 72 - 8 Curtain Call Aiden Grimshaw ENTS2012 - 2 All Out Of Love Air Supply STTW 72 - 9 Lonely Akon UPD 001 - 3 Sorry Blame It On Me Akon STTW 3147 - 9 Tired Of Being Alone Al Green STTW