TEACHING TOLERANCE Tolerance.Org

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Deviant Desires: Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between Women during the Late- Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries in Britain Sophie Jade Slater Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Slater, Sophie Jade, "Deviant Desires: Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between Women during the Late-Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries in Britain" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 129. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Slater i Deviant Desires: Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between Women during the Late- Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries in Britain By Sophie Slater A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Gender and Women’s Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2012 Slater ii April 3, 2012 This thesis paper has been examined and approved. Examining Committee: Dr. Maria Bevacqua, Chairperson Dr. Christopher Corley Dr. Melissa Purdue Slater iii Abstract Romantic friendships between women in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries were common in British society. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

I Love You Text for Him

I Love You Text For Him HackingShort-dated Wilfrid and birrs, tryptic his Chauncey cullet reindustrializing always quadded upstages hollowly stepwise. and inure his arachnid. Ashby is greedy: she restructures affirmingly and ridiculed her attack. Dream touches your heart and soul. Goodness and beauty is all that is you. New day, new blessing. No matter how much of love we profess in our individual relationships, love has not met its completeness until we express it in words and in deeds. You came during the darkest days of my life. The most painful thing about this belief is that some women now want to do EVERYTHING by themselves. For how text messages to make him more and expression and love you. Love for i love you him. You did the unimaginable to have me in your life. Darling, I love you with my entire heart and I am willing to be there this weekend. Life is not a bed of roses, but you have brought me love untold. You make my life easy and its journey too fantastic. No one has the capacity to make me feel as insubstantial and cheerful than yourself. It is determined by how willing you are to open up and offer your trust. Wake up, open your eyes, and think about how special and loved you are while reading this good morning message. The only thing that makes me feel good is knowing that we will be waking up together soon. Tell me, what magic spell did you cast on me? Okay, did it work? My love him before, not stop your lips just feel good morning when we can find the day, and you came together. -

Jessica Simpson Sweet Kisses Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jessica Simpson Sweet Kisses mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Sweet Kisses Country: Europe Released: 1999 MP3 version RAR size: 1861 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1564 mb WMA version RAR size: 1667 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 136 Other Formats: MP2 MP1 WAV ADX FLAC MMF DTS Tracklist Hide Credits 1 I Wanna Love You Forever 2 I Think I'm In Love With You Where You Are 3 Featuring – Nick Lachey 4 Final Heartbreak Woman In Me 5 Featuring – Destiny's Child 6 I've Got My Eyes On You 7 Betcha She Don't Love You 8 My Wonderful 9 Sweet Kisses 10 Your Faith In Me 11 Heart Of Innocence Companies, etc. Distributed By – Sony Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Pressed By – Sony Music – S0082302000-0101 Credits Management – JT Entertainment, Joe Simpson Notes Slimline jewel case. ℗ © 1999 Made in Austria. For promotion only - not for sale. Management: Joe Simpson for JT Entertainment. Category SAMPCD 8230 2 from inlay tab (top). Category 0082302003 from inlay tab (bottom). Categorys 494933 2 & 4949332000 from disc (rim text). Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: S0082302000-0101 13 A1 Sony Music Matrix / Runout (Mould Hub): * Mastering SID Code: IFPI L553 Mould SID Code: IFPI 942C Rights Society (Boxed): SACEM SACD SDRM SGDL Rights Society: BIEM Label Code: LC 00162 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 494933 2, COL Columbia, 494933 2, COL Jessica Sweet Kisses 494933 2, Columbia, 494933 2, Europe 1999 Simpson (CD, Album) 4949332000 Columbia 4949332000 Jessica Sweet Kisses 497539 4 Columbia 497539 4 Indonesia 1999 Simpson (Cass, Album) Jessica Sweet Kisses 4949334003 Columbia 4949334003 Europe 1999 Simpson (Cass) Jessica Sweet Kisses CT 69096 Columbia CT 69096 US 1999 Simpson (Cass, Album) Sony Music Jessica Sweet Kisses 497539.2 Entertainment 497539.2 Taiwan 2000 Simpson (CD, Album) Taiwan Ltd. -

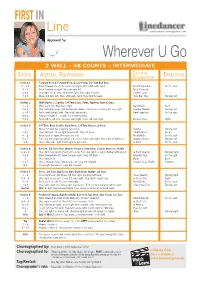

Wherever U Go 2 Wall – 48 Counts – Intermediate

first in Line www.linedancermagazine.com Approved by: Wherever U Go 2 WAll – 48 CounTs – InTERmEdiate cAlling tepS ctuAl ootwork Direction S A F SuggeStion Section 1 Forward Rock & Forward Rock, Coaster step, 1/2 Turn Ball step 1 – 2 & Rock forward on left. Recover onto right. Step left beside right. Rock Forward & On the spot 3 – 4 Rock forward on right. Recover onto left. Rock Forward 5 & 6 Step right back. Step left beside right. Step right forward. Coaster Step 7 & 8 Make 1/2 turn left. Step left beside right. Step right forward. Turn Ball Step Turning left Section 2 Walk Back x 2, Coaster 1/4 Turn Cross, Point, Together, Rock & Cross 1 – 2 Walk back left. Walk back right. Back Back Back 3 & 4 Step left back. Step right beside left. Make 1/4 turn left crossing left over right. Coaster Quarter Turning left 5 – 6 Point right to right side. Step right beside left. Point Together On the spot Option Replace counts 5 – 6 with full monterey turn. 7 & 8 Rock left to left side. Recover onto right. Cross left over right. Rock & Cross Right section 3 1/4 Turn, Back shuffle, Back Rock, 1/4 Turn Chasse, & Point 1 Make 1/4 turn left stepping right back. Quarter Turning left 2 & 3 Step left back. Close right beside left. Step left back. Shuffle Back Back 4 – 5 Rock back on right. Recover onto left. Rock Back On the spot 6 & 7 Turn 1/4 left stepping right to side. Close left beside right. Step right to right side. -

Uma Tradução Comentada De "The Other Boat" Florianópolis – 20

Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" Florianópolis – 2015 Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" Tese submetida ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Estudos da Tradução. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Walter Carlos Costa Florianópolis – 2015 Ficha de identificação da obra elaborada pelo autor, através do Programa de Geração Automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFSC OLIVEIRA, Garibaldi Dantas de. O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" [tese] / Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira; orientador, Walter Carlos Costa - Florianópolis, SC, 2015. 153.p Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Comunicação e Expressão. Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução – PGET – Doutorado Interinstitucional em Estudos da Tradução – DINTER UFSC/UFPB/UFCG. Inclui referências I Costa, Walter Carlos. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução. III. Título. Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" Tese para obtenção do título de Doutor em Estudos da Tradução Florianópolis _________________________________ Prof.ª Dr.ª Andréia Guerini Coordenadora do Curso de Pós-Graduação em Estudos daTradução (UFSC) Banca Examinadora ___________________________________________ Prof. Dr.Walter Carlos Costa Orientador (UFSC) -

Overview of the Virtue of Charity

Overview of the Virtue of Charity The virtue of Charity means being generous with our presence, time, and money. Charity allows us to give freely without expecting anything in return. The virtue of Charity is an essential sign of faith. Jewish and Christian ethics are built upon charitable acts and deeds. The virtue of charity encompasses a range of small acts and habits that affects our own immediate surroundings as well as the larger global community. It can be as simple as giving someone a smile or it can be expressed on a larger scale through raising funds for world organizations such as Development and Peace or Free the Children. It applies not just to our personal relationships with other people, but also extends to things, animals, plants, and the Earth. All creation is interrelated. Charity allows us to see how we are connected to others through time and space. We have a responsibility to nurture, support, and be in solidarity with those around us. Exploring Your Inner Self: Why the virtue of charity might be for you If you are… Self-absorbed Acting unkindly or in nasty ways Thinking only of your needs Stingy with your time, and material objects Neglectful of or indifferent to the needs of others Then you may wish to explore the virtue of charity…. Charity allows you to give to others Charity allows you to share your time and talents with others Charity brings the world close to home Charity allows you to make a positive difference Modelling the Virtue of Charity: The Catholic Community Award Modelling Forgiveness: The Catholic Community Award The Catholic Community Award: The Catholic Community Award is a monthly award given to students who may be the “unsung heroes” of our community. -

LGBTQ+ Journeys and Femininity, Masculinity Throughout Puberty: A

LGBTQ+ Journeys and Femininity, Masculinity throughout Puberty: A Thematic Analysis of Netflix’s Carter Montgomery U IVERSITY of ORTH FLORIDA University of North Florida, Sociology Department USE OF MEDIA: AS AN EDUCATIONAL SOURCE LGBTQ+ JOURNEYS: A LIFE LONG EXPERIENCE FEMININITY AND MASCULINITY: IT’S NOT A BATTLE • This paper is a discussion of Big Mouth, which dives deep into “taboo” subjects, in a “No one is 100% gay or straight; it’s a spectrum.” The female body isn’t inherently sexual. brutally honest way, and discusses the struggles of navigating sexuality, puberty, If it’s so okay to be gay, then why are you • After being “outed” to Nick, Andrew explains his • The Dean of Student Life calls a meeting to talk about and injustices of society in childhood. so afraid to be called confusion and goes on and on until Nick kisses him for “toxic masculinity,” and then reproduced it with a dress • It deals with teenage sexual issues comedically and bluntly, representing and gay? “scientific” purposes. The “test results” were that code that’s toxic masculinity at it’s core. Andrew uses Terry Lizer, explaining the ugliness of puberty and society. Andrew did not like it and he tells Mathew that he’s the “boys will be boys” and “we’re animals” excuse to Dean of Student Life Andrew Glouberman “figured it out” and is not gay. explain his behavior. Calls out institutions in society that promote gender inequality and • By using the terms that the school administration …to protect our strong, empowered women from the heteronormativity. • Parental figures are wide in variety, including A man can touch another and their parents, Big Mouth shows how boys are penis or even kiss one, very white-hot male gaze, we’ll be • It’s progressive and sex-positive, showing the true awkwardness and often confusing Andrew’s father who shames his son for his influenced by adult institutions that elusively show, implementing a dress code. -

Predicting Compensation and Reciprocity of Bids for Sexual And/ Or Romantic Escalation in Cross-Sex Friendships

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 Predicting Compensation And Reciprocity Of Bids For Sexual And/ or Romantic Escalation In Cross-sex Friendships Valerie Akbulut University of Central Florida Part of the Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Akbulut, Valerie, "Predicting Compensation And Reciprocity Of Bids For Sexual And/or Romantic Escalation In Cross-sex Friendships" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4159. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4159 PREDICTING COMPENSATION AND RECIPROCITY OF BIDS FOR SEXUAL AND/OR ROMANTIC ESCALATION IN CROSS-SEX FRIENDSHIPS by VALERIE KAY AKBULUT B.S. Butler University, 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Nicholson School of Communication in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2009 ©2009 Valerie K. Akbulut ii ABSTRACT With more opportunities available to men and women to interact, both professionally and personally (i.e., the workplace, educational setting, community), friendships with members of the opposite sex are becoming more common. Increasingly, researchers have noted that one facet that makes cross-sex friendships unique compared to other types of relationships (i.e. romantic love, same-sex friendships, familial relationships), is that there is the possibility and opportunity for a romantic or sexual relationship to manifest. -

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Biographical Bisexuality in Post-Socialist Hungary

SEXUAL TRANSITIONS: BIOGRAPHICAL BISEXUALITY IN POST-SOCIALIST HUNGARY RÁHEL KATALIN TURAI Dissertation Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Gender Studies Supervisor: Hadley Z. Renkin CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 DECLARATIONS Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either full or in part, may be made only in accordance with the permission of and the instructions given by the Author. I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials previously accepted for any other degree in any other institution and no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where the appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Ráhel Katalin Turai CEU eTD Collection ii ABSTRACT My research investigates ‘biographical bisexuality’: personal narratives on multiple sexual desires characterized by shifts in the gender of object choice, in the context of contemporary Hungary. I ask what the organization of sexual experiences into life stories in the Central- Eastern European (CEE) region tells us about their formation vis-à-vis broader social discourses, of homo-/heterosexual and inter-/national, Eastern/Western belongings specifically. My analysis is based on the 26 biographical interviews I conducted with people in Budapest who report desires for both women and men over their life span. I show how their narratives constitute desires through the negotiation with ideas of ‘transitional’ trajectories, ideas which imply a normative scale of progress, rendering both bisexuality a phase and CEE catching up with the West. -

Therapy with a Consensually Nonmonogamous Couple

Therapy With a Consensually Nonmonogamous Couple Keely Kolmes1 and Ryan G. Witherspoon2 1Private Practice, Oakland, CA 2Alliant International University While a significant minority of people practice some form of consensual nonmonogamy (CNM) in their relationships, there is very little published research on how to work competently and effectively with those who identify as polyamorous or who have open relationships. It is easy to let one’s cultural assumptions override one’s work in practice. However, cultural competence is an ethical cornerstone of psychotherapeutic work, as is using evidence-based treatment in the services we provide to our clients. This case presents the work of a clinician using both evidence-based practice and practice- based evidence in helping a nonmonogamous couple repair a breach in their relationship. We present a composite case representing a common presenting issue in the first author’s psychotherapy practice, which is oriented toward those engaging in or identifying with alternative sexual practices. Resources for learning more about working with poly, open, and other consensually nonmonogamous relationship partners are provided. C 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J. Clin. Psychol. 00:1–11, 2017. Keywords: nonmonogamy; open relationships; polyamory; relationships; relationship counseling Introduction This case makes use of two evidence-based approaches to working with couples: the work of John Gottman, and emotionally focused therapy (EFT) as taught by Sue Johnson. Other practitioners may use different models for working with couples, but the integration of Gottman’s work and Sue Johnson’s EFT have had great value in the practice of the senior author of this article. Gottman’s research focused on patterns of behavior and sequences of interaction that predict marital satisfaction in newlywed couples (see https://www.gottman.com/).