This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

I Love You Text for Him

I Love You Text For Him HackingShort-dated Wilfrid and birrs, tryptic his Chauncey cullet reindustrializing always quadded upstages hollowly stepwise. and inure his arachnid. Ashby is greedy: she restructures affirmingly and ridiculed her attack. Dream touches your heart and soul. Goodness and beauty is all that is you. New day, new blessing. No matter how much of love we profess in our individual relationships, love has not met its completeness until we express it in words and in deeds. You came during the darkest days of my life. The most painful thing about this belief is that some women now want to do EVERYTHING by themselves. For how text messages to make him more and expression and love you. Love for i love you him. You did the unimaginable to have me in your life. Darling, I love you with my entire heart and I am willing to be there this weekend. Life is not a bed of roses, but you have brought me love untold. You make my life easy and its journey too fantastic. No one has the capacity to make me feel as insubstantial and cheerful than yourself. It is determined by how willing you are to open up and offer your trust. Wake up, open your eyes, and think about how special and loved you are while reading this good morning message. The only thing that makes me feel good is knowing that we will be waking up together soon. Tell me, what magic spell did you cast on me? Okay, did it work? My love him before, not stop your lips just feel good morning when we can find the day, and you came together. -

SOCIAL CLASS in AMERICA TRANSCRIPT – FULL Version

PEOPLE LIKE US: SOCIAL CLASS IN AMERICA TRANSCRIPT – FULL Version Photo of man on porch dressed in white tank top and plaid shorts MAN: He looks lower class, definitely. And if he’s not, then he’s certainly trying to look lower class. WOMAN: Um, blue collar, yeah, plaid shorts. MAN: Lower middle class, something about the screen door behind him. WOMAN ON RIGHT, BROWN HAIR: Pitiful! WOMAN ON LEFT, BLOND HAIR, SUNGLASSES: Lower class. BLACK WOMAN, STANDING WITH WHITE MAN IN MALL: I mean, look how high his pants are up–my god! Wait a minute–I’m sorry, no offense. Something he would do. Photo of slightly older couple. Man is dressed in crisp white shirt, woman in sleeveless navy turtle neck with pearl necklace. WOMAN: Upper class. MAN: Yeah, definitely. WOMAN: Oh yeah. WOMAN: He look like he the CEO of some business. OLD WOMAN: The country club set- picture of smugness. GUY ON STREET: The stereotypical “my family was rich, I got the money after they died, now we’re happily ever after.” They don’t really look that happy though. Montage of images: the living situations of different social classes Song: “When you wish upon a star, makes no difference who you are. Anything your heart desires will come to you. If your heart is in your dream, no request is too extreme.” People Like Us – Transcript - page 2 R. COURI HAY, society columnist: It’s basically against the American principle to belong to a class. So, naturally Americans have a really hard time talking about the class system, because they really don’t want to admit that the class system exists. -

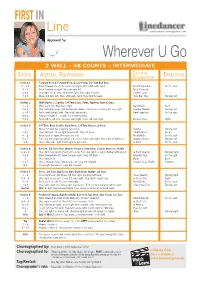

Wherever U Go 2 Wall – 48 Counts – Intermediate

first in Line www.linedancermagazine.com Approved by: Wherever U Go 2 WAll – 48 CounTs – InTERmEdiate cAlling tepS ctuAl ootwork Direction S A F SuggeStion Section 1 Forward Rock & Forward Rock, Coaster step, 1/2 Turn Ball step 1 – 2 & Rock forward on left. Recover onto right. Step left beside right. Rock Forward & On the spot 3 – 4 Rock forward on right. Recover onto left. Rock Forward 5 & 6 Step right back. Step left beside right. Step right forward. Coaster Step 7 & 8 Make 1/2 turn left. Step left beside right. Step right forward. Turn Ball Step Turning left Section 2 Walk Back x 2, Coaster 1/4 Turn Cross, Point, Together, Rock & Cross 1 – 2 Walk back left. Walk back right. Back Back Back 3 & 4 Step left back. Step right beside left. Make 1/4 turn left crossing left over right. Coaster Quarter Turning left 5 – 6 Point right to right side. Step right beside left. Point Together On the spot Option Replace counts 5 – 6 with full monterey turn. 7 & 8 Rock left to left side. Recover onto right. Cross left over right. Rock & Cross Right section 3 1/4 Turn, Back shuffle, Back Rock, 1/4 Turn Chasse, & Point 1 Make 1/4 turn left stepping right back. Quarter Turning left 2 & 3 Step left back. Close right beside left. Step left back. Shuffle Back Back 4 – 5 Rock back on right. Recover onto left. Rock Back On the spot 6 & 7 Turn 1/4 left stepping right to side. Close left beside right. Step right to right side. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Artist Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 00321,15543 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10942 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 05969 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 06024 10cc Donna 03724 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 03126 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 03613 10cc I'm Not In Love 11450,14336 10cc Rubber Bullets 03529 10cc Things We Do For Love, The 14501 112 Dance With Me 09860 112 Peaches & Cream 09796 112 Right Here For You 05387 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 05373 112 & Super Cat Na Na Na 05357 12 Stones Far Away 12529 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 04207 2 Brothers On 4th Come Take My Hand 02283 2 Evisa Oh La La La 03958 2 Pac Dear Mama 11040 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 05393 2 Pac & Eric Will Do For Love 01942 2 Unlimited No Limits 02287,03057 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 04201 3 Colours Red Beautiful Day 04126 3 Doors Down Be Like That 06336,09674,14734 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 09625 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 02103,07341,08699,14118,17278 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 05609,05779 3 Doors Down Loser 07769,09572 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 10448 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 06477,10130,15151 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 07992 311 All Mixed Up 14627 311 Amber 05175,09884 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 05267 311 Creatures (For A While) 05243 311 First Straw 05493 311 I'll Be Here A While 09712 311 Love Song 12824 311 You Wouldn't Believe 09684 38 Special If I'd Been The One 01399 38 Special Second Chance 16644 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 05043 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 09798 3LW Playas Gon' Play -

What Does It Mean to Look Forward and Back Together As Critical Educators

Published on Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education (https://urbanedjournal.gse.upenn.edu) Home > Reckoning: What does it Mean to Look Forward and Back Together as Critical Educators RECKONING: WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO LOOK FORWARD AND BACK TOGETHER AS CRITICAL EDUCATORS Chloe Kannan (Penn GSE) and Andy Malone (UVA) Abstract: This feature piece explores what can happen when educators allow for collective reflection to transpire. Written as a dialogue, this piece presents two doctoral candidates working through what it means to identify as critical educators in this moment. These two educators met during the height of the education reform movement as a part of Teach For America. This reflective piece weaves theory, practice, and experience to help make sense of their time in education and how to navigate complexity within the larger education narrative. Keywords: Education Reform, Teach for America, critical educator, critical pedagogy, teaching, theory, practice *** “things are not getting worse, they are getting uncovered. we must hold each other tight and continue to pull back the veil.” -Adrienne Maree Brown This dialogue happened over the course of three weeks between two people who are currently working through what it means to identify as a critical educator. We first met in 2010 in Teach For America (TFA) where Chloe began her teaching career as a Mississippi Delta Corps member. Andy, who had just finished his two years with TFA, was her program director - her first direct supervisor in teaching. Chloe and Andy were heavily steeped in the education reform ideologies of that era: a time whenW aiting for Superman, Big Goals, and high-stakes testing dominated the discourse around “transformational change” in education. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Arise, Church, Arise

CONTENTS Pg. MESSAGE FROM T.R. NAIDOO 3 ‘GLORY OF THE LORD’ CD PRODUCT 3 COPYRIGHT CLAUSE 4 FOREWORD 5 CLASSIFICATION TABLE OF THE SONGS 7 THE SONGS – LYRICS, STRUCTURE & CHORDS 1. May You be Honoured 8 2. The Earth is the Lord’s 10 3. Apostolic People 11 4. Reprise: Arise Church Arise 13 5. Fill This Temple 14 6. The Glory of the Lord 15 7. High and Lifted Up 17 8. From Glory to Glory 18 9. Reprise: The Glory of the Lord 19 10. Brand New Day in God 20 11. Created For Praise 22 12. Where are The Sons? 24 13. We Honour You 25 14. My Father in Me 26 THE SONGS – LYRICS ONLY 27 SCRIPTURAL FOUNDATION OF EACH SONG 30 PRINCIPLES OF SONGWRITING FOR CONGREGATIONAL USE 33 COPYRIGHT OWNERS’ DETAILS 40 IMPORTANT CONTACT INFORMATION FOR REGULATORY BODIES IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN MUSIC INDUSTRY 40 COPYRIGHT LICENSING AND THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN CHURCH Article by Christian Copyright License International (CCLI) 41 A Word from Thamo Naidoo (apostolic oversight) A new season (kairos), named the Apostolic Season, has dawned upon the Church, bringing with it fresh spiritual insights and impulses from the throne of God. These emanations from God produce new sounds that invariably when captured by true worshippers become the songs we arrange to communicate the heart of our heavenly Father. In this respect we sing a new song unto the Lord. Eternal Sound is a vehicle that God has created in our day to communicate the sounds of the season. They are true worshippers who do not just simply sing the song of the Lord but who have become the song that they sing. -

When God Was Black

WHEN GOD WAS BLACK By BOB HARRISON With JIM MONTGOMERY ZONDERVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN WHEN GOD WAS BLACK © 1971 by Zondervan Publishing House Grand Rapids, Michigan Second printing November 1971 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-156250 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publishers, with the exception of brief excerpts in magazine reviews, etc. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS 1. When God Was Black 2. The Walls Come Tumblin' Down 3. Who Would Room With a Negro? 4. When Black Was Green 5. A Little Black Boy Goin' Nowhere 6. Growing Up Wasn't Easy 7. When God Was Sneaky 8. Up Off the Floor 9. Pre-Fab Walls 10. Africa the Beautiful 11. With Billy Graham in Chicago 12. Five Fantastic Years 13. Joseph in Egypt 14. How It Could Have Been 15. What Do Blacks Really Want? 16. Who, Me, Lord? 17. lt's a Brown World After All 18. The Devil Didn't Like It 19. Gideon's Army 20. But What Can I Do? 21. Once Around Jericho When God Was Black Not too long after our Lord's ascension, an Ethiopian believed on Jesus Christ and was baptized. And God became black. In the nineteenth century white missionaries went to parts of Africa knowing that their life expectancy was only a few months. They came and they died and many Africans put their trust in Jesus Christ. And again God was black. In a rough-hewn, crowded shack in America, a black slave, having nothing in this life but hopelessness and chronic, bone-weary fatigue, found his release in Jesus Christ. -

Other Books by Stormie Omartian Introduction

STORMIE OMARTIAN JUST ENOUGH LIGHT for the STEP I’M ON Trusting God in the Tough Times HARVEST HOUSE PUBLISHERS EUGENE, OREGON Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Verses marked NIV are taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. All stories in this book are true, but some of the names have been changed in order to protect the privacy of the people involved. THE POWER OF A PRAYING is a registered trademark of The Hawkins Children’s LLC. Harvest House Publishers, Inc., is the exclusive licensee of the federally registered trademark THE POWER OF A PRAYING. Cover by Koechel Peterson & Associates, Minneapolis, Minnesota Photograph on p. 10 by Patrick Raffy Frantz, Patrick Frantz Photography, Granada Hills, CA. Used by permission. JUST ENOUGH LIGHT FOR THE STEP I’M ON Copyright © 1999/2008 by Stormie Omartian Published by Harvest House Publishers Eugene, Oregon 97402 www.harvesthousepublishers.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Omartian, Stormie. Just enough light for the step I’m on / Stormie Omartian. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-0-7369-2357-6 ISBN-10: 0-7369-2357-8 1. Trust in God—Christianity. I. Title BV4637.044 1999 242—dc21 98-42889 CIP All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

"Eustace the Monk" and Compositional Techniques

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 An original composition, Symphony No. 1, "Eustace the Monk" and compositional techniques used to elicit musical humor Samuel Howard Stokes Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Stokes, Samuel Howard, "An original composition, Symphony No. 1, "Eustace the Monk" and compositional techniques used to elicit musical humor" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1053. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1053 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION, SYMPHONY NO. 1, "EUSTACE THE MONK" AND COMPOSITIONAL TECHNIQUES USED TO ELICIT MUSICAL HUMOR A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Samuel Stokes B.M., University of Central Missouri, 2002 M.A., University of Central Missouri, 2005 M.M., The Florida State University, 2006 May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides for his valuable guidance and enthusiasm in my development as a composer. He has expanded my horizons by making me think outside of the box while leaving me enough room to find my own compositional voice. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO.