The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) It Is Important to Understand How Palestinian Views Have Changed Over the Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Terrorism: Individuals: Atta [Mahmoud] Box: RAC Box 8](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1820/terrorism-individuals-atta-mahmoud-box-rac-box-8-11820.webp)

Terrorism: Individuals: Atta [Mahmoud] Box: RAC Box 8

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Counterterrorism and Narcotics, Office of, NSC: Records Folder Title: Terrorism: Individuals: Atta [Mahmoud] Box: RAC Box 8 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name COUNTERTERRORISM AND NARCOTICS, NSC: Withdrawer RECORDS SMF 5/12/2010 File Folder TERRORISM: INDNIDUALS: ATTA [ITA, MAHMOUD] FOIA TED MCNAMARA, NSC STAFF F97-082/4 Box Number _w;:w (2j!t t ~ '( £ WILLS 5 ID Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions Pages 91194 REPORT RE ABU NIDAL ORGANIZATION (ANO) 1 ND Bl B3 - ·-----------------·--------------- ------ -------- 91195 MEMO CLARKE TO NSC RE MAHMOUD ITA 2 5/6/1987 B 1 B3 ---------------------- ------------ ------ ------ ----- ----------- 91196 MEMO DUPLICATE OF 91195 2 5/6/1987 Bl B3 91197 REPORT REATTA 1 ND Bl 91198 CABLE STATE 139474 2 5112/1987 Bl 91199 CABLE KUWAIT 03413 1 5/2111987 Bl -- - - - - --------- - - -- - ----------------- 91200 CABLE l 5 l 525Z MAR 88 (1 ST PAGE ONLY) 1 3/15/1988 Bl B3 The above documents were not referred for declassification review at time of processing Freedom of Information -

Terrorist Links of the Iraqi Regime | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 652 Terrorist Links of the Iraqi Regime Aug 29, 2002 Brief Analysis n August 28, 2002, a U.S. federal grand jury issued a new indictment against five terrorists from the Fatah O Revolutionary Command, also known as the Abu Nidal Organization (ANO), for the 1986 hijacking of Pan Am Flight 73 in Karachi, Pakistan. Based on "aggravating circumstances," prosecutors are now seeking the death penalty for the attack, in which twenty-two people -- including two Americans -- were killed. The leader of the ANO, the infamous Palestinian terrorist Abu Nidal (Sabri al-Banna), died violently last week in Baghdad. But his death is not as extraordinary as the subsequent press conference given by Iraqi intelligence chief Taher Jalil Haboush. This press conference represents the only time Haboush's name has appeared in the international media since February 2001. Iraqi Objectives What motivated the Iraqi regime to send one of its senior exponents to announce the suicide of Abu Nidal and to present crude photographs of his bloodied body four days (or eight days, according to some sources) after his death? It should be noted that the earliest information about Nidal's death came from al-Ayyam, a Palestinian daily close to the entity that may have been Abu Nidal's biggest enemy -- the Palestinian Authority. At this sensitive moment in U.S.-Iraqi relations, Abu Nidal could have provided extraordinarily damaging testimony with regard to Saddam's involvement in international terrorism, even beyond Iraqi support of ANO activities in the 1970s and 1980s. In publicizing Nidal's death, the regime's motives may have been multiple: • To present itself as fighting terrorism by announcing that Iraqi authorities were attempting to detain Abu Nidal for interrogation in the moments before his death. -

The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

THE ORIGINS OF HAMAS: MILITANT LEGACY OR ISRAELI TOOL? JEAN-PIERRE FILIU Since its creation in 1987, Hamas has been at the forefront of armed resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the move- ment itself claims an unbroken militancy in Palestine dating back to 1935, others credit post-1967 maneuvers of Israeli Intelligence for its establishment. This article, in assessing these opposing nar- ratives and offering its own interpretation, delves into the historical foundations of Hamas starting with the establishment in 1946 of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (the mother organization) and ending with its emergence as a distinct entity at the outbreak of the !rst intifada. Particular emphasis is given to the Brotherhood’s pre-1987 record of militancy in the Strip, and on the complicated and intertwining relationship between the Brotherhood and Fatah. HAMAS,1 FOUNDED IN the Gaza Strip in December 1987, has been the sub- ject of numerous studies, articles, and analyses,2 particularly since its victory in the Palestinian legislative elections of January 2006 and its takeover of Gaza in June 2007. Yet despite this, little academic atten- tion has been paid to the historical foundations of the movement, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Gaza branch established in 1946. Meanwhile, two contradictory interpretations of the movement’s origins are in wide circulation. The !rst portrays Hamas as heir to a militant lineage, rigorously inde- pendent of all Arab regimes, including Egypt, and harking back to ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam,3 a Syrian cleric killed in 1935 while !ghting the British in Palestine. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government. -

RESPONSES to INFORMATION REQUESTS (Rirs) Page 1 of 2

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 03 April 2006 JOR101125.E Jordan: The "Arab National Movement" and treatment of its members by authorities (January 1999 - March 2006) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa Information on the Arab National Movement (ANM) in Jordan was scarce among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate. The ANM is described as a Marxist political party (Political Handbook of the Middle East 2006 2006, 238) founded in Beirut in 1948 following the founding of the State of Israel (HRW Oct. 2002; CDI 23 Oct. 2002). The ANM was founded (IPS n.d.) and led by George Habash who went on to create the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PLFP) (ibid.; HRW Oct. 2002). According to the Center for Defense Information (CDI), a part of the World Security Institute (WSI), which is a research institute supported by public charity and based in Washington, DC (CDI n.d.), the ANM "spread quickly throughout the Arab World" (ibid. 23 Oct. 2002). The CDI added that the ANM was allied with Egypt's Gamal Abdul- Nasser, with whom it shared views on "a unified, free and socialist Arab world with an autonomous Palestine" (ibid.). The Political Handbook of the Middle East 2006 stated that in a 1989 Jordanian poll, the ANM was one of several political parties supporting independent political candidates (2006, 238). The most recent media report on the ANM found by the Research Directorate was from the 29 August 1999 issue of the Jerusalem-based Al-Quds newspaper, which reported that members of the ANM were part of a subcommittee to the Jordanian Opposition Parties' Coordinating Committee, made up of the 14 Jordanian opposition parties. -

THE PLO and the PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London

THE PLO AND THE PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London The emergence of a durable Palestinian nationalism was one of the more remarkable developments in the history of the modern Middle East in the second half of the 20th century. This was largely due to a generation of young activists who proved particularly adept at capturing the public imagination, and at seizing opportunities to develop autonomous political institutions and to promote their cause regionally and internationally. Their principal vehicle was the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), while armed struggle, both as practice and as doctrine, was their primary means of mobilizing their constituency and asserting a distinct national identity. By the end of the 1970s a majority of countries – starting with Arab countries, then extending through the Third World and the Soviet bloc and other socialist countries, and ending with a growing number of West European countries – had recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. The United Nations General Assembly meanwhile confirmed the right of the stateless Palestinians to national self- determination, a position adopted subsequently by the European Union and eventually echoed, in the form of support for Palestinian statehood, by the United States and Israel from 2001 onwards. None of this was a foregone conclusion, however. Britain had promised to establish a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine when it seized the country from the Ottoman Empire in 1917, without making a similar commitment to the indigenous Palestinian Arab inhabitants. In 1929 it offered them the opportunity to establish a self-governing agency and to participate in an elected assembly, but their community leaders refused the offer because it was conditional on accepting continued British rule and the establishment of the Jewish ‘national home’ in what they considered their own homeland. -

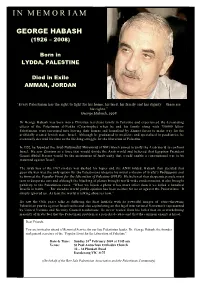

BPA in Memoriam G. Habash 24 Feb 08

IN MEMORIAM GEORGE HABASH (1926 – 2008) Born in LYDDA, PALESTINE Died in Exile AMMAN, JORDAN “Every Palestinian has the right to fight for his home, his land, his family and his dignity – these are his rights.” George Habash, 1998 Dr George Habash was born into a Christian merchant family in Palestine and experienced the devastating effects of the Palestinian al-Nakba (Catastrophe) when he and his family along with 750,000 fellow Palestinians were terrorised into leaving their homes and homeland by Zionist forces to make way for the artificially created Jewish state, Israel. Although he graduated in medicine and specialised in paediatrics, he eventually devoted his time to the life-long struggle for the liberation of Palestine. In 1952, he founded the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM) which aimed to unify the Arab world to confront Israel. He saw Zionism as a force that would divide the Arab world and believed that Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser would be the instrument of Arab unity that would enable a conventional war to be mounted against Israel. The Arab loss of the 1967 six-day war dashed his hopes and the ANM folded. Habash then decided that guerrilla war was the only option for the Palestinians (despite his initial criticism of Arafat’s Fedayyeen) and he formed the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). He believed that desperate people must turn to desperate acts and although the hijacking of planes brought world-wide condemnation, it also brought publicity to the Palestinian cause. “When we hijack a plane it has more effect than if we killed a hundred Israelis in battle . -

Palestine PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY and ISRAELI-OCCUPIED TERRITORIES by Suheir Azzouni

palestine PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY AND ISRAELI-OCCUPIED TERRITORIES by Suheir Azzouni POPULATION: 3,933,000 GNI PER CAPITA: US$1,519 COUNTRY RATINGS 2004 2009 NONDISCRIMINATION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE: 2.6 2.6 AUTONOMY, SECURITY, AND FREEDOM OF THE PERSON: 2.7 2.4 ECONOMIC RIGHTS AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY: 2.8 2.9 POLITICAL RIGHTS AND CIVIC VOICE: 2.6 2.7 SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS: 2.9 2.6 (COUNTRY RATINGS ARE BASED ON A SCALE OF 1 TO 5, WITH 1 REPRESENTING THE LOWEST AND 5 THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF FREEDOM WOMEN HAVE TO EXERCISE THEIR RIGHTS) INTRODUCTION Palestinian women have been socially active since the beginning of the 20th century, forming charitable associations, participating in the nation- alist struggle, and working for the welfare of their community. Originally established in Jerusalem in 1921, the General Union of Palestinian Women organized women under occupation and in the Palestinian diaspora so that they could sustain communities and hold families together. The character of women’s involvement shifted in the late 1970s, as young, politically oriented women became active in the fi ght against Israeli occupation, as well as in the establishment of cooperatives, training cen- ters, and kindergartens. They formed activist women’s committees, which were able to attract members from different spheres of life and create alli- ances with international feminist organizations. Women also played an ac tive role in the fi rst intifada, or uprising, against Israeli occupation in 1987, further elevating their status in the society. Soon after the beginning of peace negotiations between the Palestinians and Israelis in 1991, which resulted in the 1993 Oslo Accord, women’s organizations formed a coalition called the Women’s Affairs Technical Committee (WATC) to advocate for the equal rights of women. -

Palestine Water Fact Sheet #1

hrough e t hu ic m t a FACT SHEET s n ju r l i a g i h c t o s THE RIGHT TO WATER IN PALESTINE: A BACKGROUND s 11 C E S R he Israeli confiscation and control of LEGEND ability to manage water resources and just Palestinian water resources is a defining Groundwater flow allocates the limited supply made available by T feature of the Israeli occupation and a LEBANON Groundwater divide Israel, the PWA, rather than the Occupation, is GOLAN major impediment to a just resolution of the Israeli National Water HEIGHTS blamed for water scarcity. Moreover, the Oslo Israel-Palestine conflict. Furthermore, Israel’s Carrier Sea of II agreement does not call for redistribution of control of Palestinian water resources Armistice Demarcation Galilee Line, 1949 existing water sources nor require any undermines any possibility for sustainable Haifa Tiberias Syria-Israel Cease Fire reduction in water extraction or consumption development and violates Palestinians’ human Line, 1967 Nazareth by Israelis or settlers. right to safe, accessible, and adequate drinking Palestinian Territory Occupied by Israel (June n Jenin a water. Israel’s discriminatory water policy 1967) d r • Since 2000, after the onset of the Second o Northern J maintains an unequal allocation of water between Aquifer r e v Intifada in September, the Israeli army has Tu l k a re m i Israel, illegal Israeli settler communities and R intensified the destruction of water infrastruc- Palestinians living in the occupied Palestinian Nablus Western ture and confiscation ofwater sources in the 7 territory (oPt), while appropriating an ever greater Te l Av i v Aquifer WEST r BANK West Bank and Gaza. -

What Drives Terrorist Innovation? Lessons from Black September And

What Drives Terrorist Innovation? Lessons from Black September and Munich 1972 Authors: Andrew Silke, Cranfield Forensic Institute, Cranfield University, Shrivenham, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Anastasia Filippidou, Centre for International Security and Resilience, Cranfield University, Shrivenham, UK. Abstract: Understanding terrorist innovation has emerged as a critical research question. Terrorist innovation challenges status quo assumptions about the nature of terrorist threats and emphasises a need for counterterrorism policy and practice to attempt to not simply react to changes in terrorist tactics and strategies but also to try to anticipate them. This study focused on a detailed examination of the 1972 Munich Olympics attack and draws on the wide range of open source accounts available, including from terrorists directly involved but also from among the authorities and victims. Using an analytical framework proposed by Rasmussen and Hafez (2010), several key drivers are identified and described, both internal to the group and external to its environment. The study concludes that the innovation shown by Black September was predictable and that Munich represented a profound security failure as much as it did successful terrorist innovation. Keywords: terrorism, terrorist innovation, Munich 1972, Black September 1 Introduction A growing body of research has attempted to identify and understand the factors associated with innovation in terrorism (e.g. Dolnik, 2007; Rasmussen and Hafez, 2010; Horowitz, 2010; Jackson and Loidolt, 2013; Gill, 2017; Rasmussen, 2017). In part this increased attention reflects a concern that more innovative terrorist campaigns might potentially be more successful and/or simply more dangerous. Successful counterterrorist measures and target hardening efforts render previous terrorist tactics ineffective, forcing terrorists to innovate and adapt in order to overcome countermeasures. -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood