Researchnote Jamaica'swindward Maroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

Destination Jamaica

© Lonely Planet Publications 12 Destination Jamaica Despite its location almost smack in the center of the Caribbean Sea, the island of Jamaica doesn’t blend in easily with the rest of the Caribbean archipelago. To be sure, it boasts the same addictive sun rays, sugary sands and pampered resort-life as most of the other islands, but it is also set apart historically and culturally. Nowhere else in the Caribbean is the connection to Africa as keenly felt. FAST FACTS Kingston was the major nexus in the New World for the barbaric triangular Population: 2,780,200 trade that brought slaves from Africa and carried sugar and rum to Europe, Area: 10,992 sq km and the Maroons (runaways who took to the hills of Cockpit Country and the Blue Mountains) safeguarded many of the African traditions – and Length of coastline: introduced jerk seasoning to Jamaica’s singular cuisine. St Ann’s Bay’s 1022km Marcus Garvey founded the back-to-Africa movement of the 1910s and ’20s; GDP (per head): US$4600 Rastafarianism took up the call a decade later, and reggae furnished the beat Inflation: 5.8% in the 1960s and ’70s. Little wonder many Jamaicans claim a stronger affinity for Africa than for neighboring Caribbean islands. Unemployment: 11.3% And less wonder that today’s visitors will appreciate their trip to Jamaica Average annual rainfall: all the more if they embrace the island’s unique character. In addition to 78in the inherent ‘African-ness’ of its population, Jamaica boasts the world’s Number of orchid species best coffee, world-class reefs for diving, offbeat bush-medicine hiking tours, found only on the island: congenial fishing villages, pristine waterfalls, cosmopolitan cities, wetlands 73 (there are more than harboring endangered crocodiles and manatees, unforgettable sunsets – in 200 overall) short, enough variety to comprise many utterly distinct vacations. -

Jamaica's True Queen Nanny of the Maroons

Jamaica's True Queen Nanny of the Maroons Prepared by Jah Rootsman ina di irit of HIGHER REASONING APRIL 2010 Jamaica's True Queen By Deborah Gabriel Published Sep 2, 2004 Nanny of the Maroons Queen Nanny is credited with being the single figure – it was founded in 1734 after the British de- who united the Maroons across Jamaica and played a stroyed the original Maroon town, which was major role in the preservation of African culture and known as ‘Nanny Town’. knowledge. Slaves imported to Jamaica from Africa Background came from the Gold Coast, the Congo and Queen Nanny of the Windward Maroons has largely Madagascar. The dominant group among been ignored by historians who have restricted their Maroon communities was from the Gold focus to male figures in Maroon history. However, Coast. In Jamaica this group was referred to amongst the Maroons themselves she is held in the as Coromantie or Koromantee. They were highest esteem. Biographical information on Queen fierce and ferocious fighters with a prefer- Nanny is somewhat vague, with her being mentioned ence for resistance, survival and above all only four times in written historical texts and usually freedom and refused to become slaves. Be- in somewhat derogatory terms. However, she is held tween 1655 until the 1830’s they led most of up as the most important figure in Maroon history. the slave rebellions in Jamaica. She was the spiritual, cultural and military leader of the Windward Maroons and her importance stems Spiritual life was of the utmost importance from the fact that she guided the Maroons through the to the Maroons which was incorporated into most intense period of their resistance against the every aspect of life, from child rearing to British, between 1725 and 1740. -

The Muslim Maroons and the Bucra Massa in Jamaica

AS-SALAAMU-ALAIKUM: THE MUSLIM MAROONS AND THE BUCRA MASSA IN JAMAICA ©Sultana Afroz Introduction As eight centuries of glorious Muslim rule folded in Andalusia Spain in 1492, Islam unfolded itself in the West Indian islands with the Andalusian Muslim mariners who piloted Columbus discovery entourage through the rough waters of the Atlantic into the Caribbean. Schooled in Atlantic navigation to discover and to dominate the sea routes for centuries, the mission for the Muslim mariners was to find the eternal peace of Islam as they left al-Andalus/Muslim Spain in a state of ‘empty husks’ and a land synonym for intellectual and moral desolation in the hands of Christendom Spain. The Islamic faith made its advent into Jamaica in1494 as these Muslim mariners on their second voyage with Columbus set their feet on the peaceful West Indian island adorned with wooded mountains, waterfalls, sandy beaches and blue seas. The seed of Islam sown by the Mu’minun (the Believers of the Islamic faith) from al-Andalus gradually propagated through the enslaved African Muslims from West Africa brought to serve the plantation system in Jamaica. Their struggle or resistance (jihad) against the slave system often in the form of flight or run away (hijra) from the plantations led many of them to form their own community (ummah), known as Maroon communities, a feature then common in the New World plantation economy.1 Isolationism and lack of Islamic learning made Islam oblivion in the Maroon societies, while the enslaved African Muslims on the plantations saw their faith being eclipsed and subdued by the slave institution, the metropolitan powers and the various Christian churches with their draconian laws. -

Jamaica Ecoregional Planning Project Jamaica Freshwater Assessment

Jamaica Ecoregional Planning Project Jamaica Freshwater Assessment Essential areas and strategies for conserving Jamaica’s freshwater biodiversity. Kimberly John Freshwater Conservation Specialist The Nature Conservancy Jamaica Programme June 2006 i Table of Contents Page Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………..... i List of Maps ………………………………………………………………. ii List of Tables ………………………………………………………………. ii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………. iii List of Boxes ………………………………………………………………. iii Glossary ………………………………………………………………. iii Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. v Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………… vi 1. Introduction and Overview …………………………………………………………..... 1 1.1 Planning Objectives……………………………………... 1 1.2 Planning Context………………………………………... 2 1.2.1 Biophysical context……………………………….. 2 1.2.2 Socio-economic context…………………………... 5 1.3 Planning team…………………………………………… 7 2. Technical Approach ………………………………………………………………….…. 9 2.1 Information Gathering…………………………………... 9 2.2 Freshwater Classification Framework…………………... 10 2.3 Freshwater conservation targets………………………… 13 2.4 Freshwater conservation goals………………………….. 15 2.5 Threats and Opportunities Assessment…………………. 16 2.6 Ecological Integrity Assessment……………………... 19 2.7 Protected Area Gap Assessment………………………… 22 2.8 Freshwater Conservation Portfolio development……….. 24 2.9 Freshwater Conservation Strategies development…….. 30 2.10 Data and Process gaps…………………………………. 31 3. Vision for freshwater biodive rsity conservation …………………………………...…. 33 3.1 Conservation Areas ………………………………….. -

From Freedom to Bondage: the Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770

From Freedom to Bondage: The Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770 Jonathan Brooks, University of North Carolina Wilmington Andrew Clark, Faculty Mentor, UNCW Abstract: The Jamaican Maroons were not a small rebel community, instead they were a complex polity that operated as such from 1655-1770. They created a favorable trade balance with Jamaica and the British. They created a network of villages that supported the growth of their collective identity through borrowed culture from Africa and Europe and through created culture unique to Maroons. They were self-sufficient and practiced sustainable agricultural practices. The British recognized the Maroons as a threat to their possession of Jamaica and embarked on multiple campaigns against the Maroons, utilizing both external military force, in the form of Jamaican mercenaries, and internal force in the form of British and Jamaican military regiments. Through a systematic breakdown of the power structure of the Maroons, the British were able to subject them through treaty. By addressing the nature of Maroon society and growth of the Maroon state, their agency can be recognized as a dominating factor in Jamaican politics and development of the country. In 1509 the Spanish settled Jamaica and brought with them the institution of slavery. By 1655, when the British invaded the island, there were 558 slaves.1 During the battle most slaves were separated from their masters and fled to the mountains. Two major factions of Maroons established themselves on opposite ends of the island, the Windward and Leeward Maroons. These two groups formed the first independent polities from European colonial rule. The two groups formed independent from each other and with very different political structures but similar economic and social structures. -

History of Portland

History of Portland The Parish of Portland is located at the north eastern tip of Jamaica and is to the north of St. Thomas and to the east of St. Mary. Portland is approximately 814 square kilometres and apart from the beautiful scenery which Portland boasts, the parish also comprises mountains that are a huge fortress, rugged, steep, and densely forested. Port Antonio and town of Titchfield. (Portland) The Blue Mountain range, Jamaica highest mountain falls in this parish. What we know today as the parish of Portland is the amalgamation of the parishes of St. George and a portion of St. Thomas. Portland has a very intriguing history. The original parish of Portland was created in 1723 by order of the then Governor, Duke of Portland, and also named in his honour. Port Antonio Port Antonio, the capital of Portland is considered a very old name and has been rendered numerous times. On an early map by the Spaniards, it is referred to as Pto de Anton, while a later one refers to Puerto de San Antonio. As early as 1582, the Abot Francisco, Marquis de Villa Lobos, mentions it in a letter to Phillip II. It was, however, not until 1685 that the name, Port Antonio was mentioned. Earlier on Portland was not always as large as it is today. When the parish was formed in 1723, it did not include the Buff Bay area, which was then part of St. George. Long Bay or Manchioneal were also not included. For many years there were disagreements between St. -

S Port Antonio and Ocho Rios by Lee Foster

Jamaica’s Port Antonio and Ocho Rios by Lee Foster The Jamaica of my experience proved to be an intriguing but challenging destination to recommend. I looked at old Port Antonio, where tourism began in Jamaica a hundred years ago. After that immersion, I visited the more modern Ocho Rios, where the newer phase of planned all-inclusive resort tourism greets the traveler. In this article, I compare these two faces of Jamaica today. The Jamaica I encountered was a Caribbean island with dependable warmth to thaw out wind-chilled northerners, with a reportedly glorious sun (even though it rained a little during my November trip), and with some lovely cream sand beaches (such as at my Dragon Bay Hotel in Port Antonio or Renaissance Jamaica Grande Resort in Ocho Rios). Port Antonio After flying into Kingston, I was driven across the mountains to Port Antonio. Be sure to have your hotel send a van to do this drive or get a local air shuttle from Kingston to Port Antonio or to Ocho Rios. The winding, potholed roads are challenging, even if you are skilled at driving on the left side of the road. Palatial villas of the rich in the hills above Kingston contrast dramatically with the grinding poverty of the countryside. If you are bothered by poverty, this island, beyond the perimeters of the all-inclusive resort, will disturb you. I admired some of the creative and energetic young Jamaicans, such as those who administer Mocking Bird Hill Hotel in Port Antonio, for trying to revitalize the area with an eco-tourism emphasis. -

Resource Directory Is Intended As a General Reference Source

National Security is our duty Our success educationally, industrially and politically is based upon the protection of a nation founded by ourselves. Rt Excellent Marcus Garvey The directory is a tool to help you find the services you need to make informed decisions for: • Your security • Your community • Our nation. The directory brings to you services available through the public sector arranged by subject area: • Care and protection of children • Local & international disease control • Protecting Natural Resources • Community Safety • Anti-Corruption Agencies. In addition you will find information for documents that you will need as a citizen of Jamaica: • National Identification • Passport • Birth Certificate • TRN Plus general information for your safety and security. The directory belongs to Name: My local police station Tel: My police community officer Tel: My local fire brigade Tel: DISCLAIMER The information available in this resource directory is intended as a general reference source. It is made available on the understanding that the National Security Policy Coordination Unit (NSPCU) is not engaged in rendering professional advice on any matter that is listed in this publication. Users of this directory are guided to carefully evaluate the information and get appropriate professional advice relevant to his or her particular circumstances. The NSPCU has made every attempt to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information that is published in this resource directory. This includes subject areas of ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) names of MDAs, website urls, telephone numbers, email addresses and street addresses. The information can and will change over time by the organisations listed in the publication and users are encouraged to check with the agencies that are listed for the most up-to-date information. -

Maroon Societies: a Political Perspective Chantal Mcfarlane

..... Maroon Societies: A Political Perspective Chantal McFarlane Chantal Noelene McFarlane is a third year student at the University of Toronto. She is presently pursuing her undergraduate degree in Caribbean Studies and English. As a proud descendant of the Accompong Town Maroons in Jamaica, she is a staunch believer in the concept of “Kindah”, One Family - she believes that this can manifest in the Caribbean in the form of regional integration. Chantal is particularly interested in the cultural, social and historical aspects of Jamaica. The act of grand marronage had a far reaching impact on slave societies. Marronage in its most simplistic sense may be described as the running away from slavery by the enslaved. In Jamaica1 slaves who absconded for great periods tended to live by themselves or join a Maroon settlement. This essay will argue that Maroon societies acted as an entity of defiance against slave communities, even though intricate organizational structures had an atypical symbiotic relationship with them. It will show that the political aspect of Maroon societies acted as a dominant factor in solidifying their relationship with slave communities. This paper will first establish that Maroons in Jamaica were more autonomous prior to 1739 and that the difference in political structures from that of the plantation was pivotal in shaping the relationship between the two societies. It will then argue that the political scope of Maroon societies impacted the culture and socio-economic organization of the Maroons. Finally it will posit the idea that a significant change in the relationship between Maroons and the plantation in Jamaica acted as an impetus which changed the political configuration of Maroon communities. -

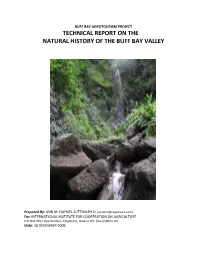

Technical Report on the Natural History of the Buff Bay Valley

BUFF BAY AGROTOURISM PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE BUFF BAY VALLEY Prepared By: ANN M. HAYNES-SUTTON PH.D. ([email protected]) For: INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR COOPERATION ON AGRICULTURE P.O. Box 349, Hope Gardens, Kingston 6, Jamaica W.I. ([email protected]) Date: 18 DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents BACKGROUND: ................................................................................................................................. 4 METHODS: ......................................................................................................................................... 4 OBJECTIVES: ...................................................................................................................................... 4 DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA: ...................................................................................................... 4 GEOLOGY ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 SOILS ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 HISTORY ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 LAND USES .................................................................................................................................................... 8 NATURAL -

List of Rivers of Jamaica

Sl. No River Name Draining Into 1 South Negril River North Coast 2 Unnamed North Coast 3 Middle River North Coast 4 Unnamed North Coast 5 Unnamed North Coast 6 North Negril River North Coast 7 Orange River North Coast 8 Unnamed North Coast 9 New Found River North Coast 10 Cave River North Coast 11 Fish River North Coast 12 Green Island River North Coast 13 Lucea West River North Coast 14 Lucea East River North Coast 15 Flint River North Coast 16 Great River North Coast 17 Montego River North Coast 18 Martha Brae River North Coast 19 Rio Bueno North Coast 20 Cave River (underground connection) North Coast 21 Roaring River North Coast 22 Llandovery River North Coast 23 Dunn River North Coast 24 White River North Coast 25 Rio Nuevo North Coast 26 Oracabessa River North Coast 27 Port Maria River North Coast 28 Pagee North Coast 29 Wag Water River (Agua Alta) North Coast 30 Flint River North Coast 31 Annotto River North Coast 32 Dry River North Coast 33 Buff Bay River North Coast 34 Spanish River North Coast 35 Swift River North Coast 36 Rio Grande North Coast 37 Black River North Coast 38 Stony River North Coast 39 Guava River North Coast 40 Plantain Garden River North Coast 41 New Savannah River South Coast 42 Cabarita River South Coast 43 Thicket River South Coast 44 Morgans River South Coast 45 Sweet River South Coast 46 Black River South Coast 47 Broad River South Coast 48 Y.S. River South Coast 49 Smith River South Coast www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 One Eye River (underground connection) South Coast 51 Hectors River (underground connection)