Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

Upper Mustang

Upper Mustang Overview Travelling through the forbidden lands of Upper Mustang is rare and a privilege. Experience the true life or real mountain people of Nepal. Trekking in this region is similar to trekking in Tibet, which geographically is part of the Upper Mustang. In the Mustang, the soul of a man is still considered to be as real as oneself. Despite the hardness of the almost treeless landscapes, with a countryside alike Tibetan plateau, beauty and happiness flourishes within the inhabitants and villages. The region was part of the Tibetan Kingdom of Gungthang until 1830’s. Lo Monthang, the unofficial capital is a fabled medieval wall city still remaining a Kingdom within the Kingdom. It is full of cultural and religious heritage. Its early history is embellished in myth and legends. The Mustang has preserved its status as an independent principality until 1951. Lo Monthang still has a King to which the rank of Colonel was given in the Nepalese Army. Required number of participants: min 2, max 12 The start dates refer to the arrival date in Kathmandu and the end date refers to the earliest you can book for our return flight home. When departing from Europe allow for an overnight flight to Kathmandu, but on the return it is possible to depart in the morning and arrive on the same day. Private trips are welcomed if the scheduled dates do not fit, although we do require a minimum of three people in any team. We have our own office and guesthouse ready and waiting for any dates you may prefer. -

Conservation Grazing.Pdf

MINNESOTA WETLAND RESTORATION GUIDE CONSERVATION GRAZING TECHNICAL GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Document No.: WRG 6A-5 Publication Date: 1/30/2014 Table of Contents Introduction Application Other Considerations Costs Additional References INTRODUCTION Grazing by bison, elk and deer was historically a natural occurrence in grassland and shrubland plant communities in Minnesota. This grazing tended to be nomadic in nature and its intensity depended on the type of grazers, herd sizes, climate conditions, fire frequency, and the composition and structure of individual plant communities. Today conservation grazing is conducted by a variety of species including cattle, bison, horses, sheep, and goats to target specific invasive plants, or to replicate the grassland plant community structure and diversity that historically resulted from grazing. When grazing is conducted to control invasive species the intensity and duration of grazing is carefully monitored to ensure that target species are managed effectively, and that the integrity of the plant community is maintained. Most conservation grazing involves a short pulse of grazing followed by a long rest. Grazing can have benefits as well as negative impacts, so it is important to involve experienced professionals. Detailed grazing plans are an important component in the planning and implementation of prescribed grazing. Equipment that may be needed for grazing includes watering systems, electric, or barb”ed” wire fences around rotational grazing areas, moveable fencing to concentrate grazing and to ensure that areas are not overgrazed, and in some cases salt licks to concentrate animals (Tu et al. 2001). The following is a list of species commonly used for conservation grazing and their general characteristics. -

Himalayan Borders and Borderlands: Mobility, State Building, and Identity

Himalayan Borders and Borderlands: Mobility, State Building, and Identity This review article engages with recent ethnographic research on ‘borders’ and ‘borderlands’ in the Himalayan region. We examine how recent scholarship published primarily between 2012-2018 engages with borderland theory as it intersects with issues of state building, ethnicity, language, religion, and tourism. As the scholarly canon moves away from disparate areas studies approaches, this paper investigates how Himalayan scholarship views borders as comprising a multivariate geographical, cultural, and political network of history and relationships undergoing continual transformation. As emerging scholars from both within and outside the Himalaya, we separate the article into four sub- sections that each connect to our respective interests. Our intention is not to propose an alternative conceptual framework or set of terminologies to borderland studies, but to bring together various inter-disciplinary approaches that view borders as sites of continuity and discontinuity, with the power to transform livelihoods for the better and at times perpetuate forms of violence and inequality. Keywords: borders, borderlands, Himalaya, mobility, state building, identity 1 Introduction How do Himalayan borders become contested spaces of continuity and discontinuity in relation to the borderland communities that occupy them, and the non-inhabitants that relate to them? How does this tension link to ongoing projects of mobility, state formation, and identity politics? This article reviews recent ethnographic research on Himalayan borders and borderlands surrounding state building, development, tourism, ethnicity, language, and religion, with a focus on material published between 2012-2018. We critically engage with notions of ‘borders’ and ‘borderlands’, to explore how recent scholarship has engaged with changing borderland theory as it reflects on Himalayan place and personhood. -

Management of Grazing Animals for Environmental Quality

Management of grazing animals for environmental quality Etienne M. in Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products Zaragoza : CIHEAM Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67 2005 pages 225-235 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6600046 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ Etienne M. Management of grazing animals for environmental quality. In : Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products . Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 225-235 (Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://www.ciheam.org/ -

Upper Mustang Trek - 17 Days

GPO Box: 384, Ward No. 17, Pushpalal Path Khusibun, Nayabazar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-01-4388659 E-Mail: [email protected] www.iciclesadventuretreks.com Upper Mustang Trek - 17 Days "Join our Upper Mustang Trek to uncover the hidden mysticism of Upper Mustang." With plenty of nature to see and culture to observe, Upper Mustang is a beautiful place to travel in. A trek inside Upper Mustang is a journey which presents travelers with a vivid blend of arid landscape & exotic cultural heritages. Upper Mustang lies near to the Tibetan border at an altitude over 4,000 meters above sea level. It encompasses Tibetan societies, scenic landscapes & compelling arrangement of bio-diversity. Due to which, it has gained vast popularity as an incredible trans-Himalayan region! Initially, trekkers get to go an outlandish venture which takes them on an off the beaten path trail. Following out of the ordinary and far-flung trek routes, trekkers are eventually rewarded with breathtakingly beautiful vistas. Learn and witness the glorious Tibetan cultures as you make your way up and through the valley’s ethnic villages; take pleasure in the scenes of yellow & grey colored hills being eroded away by the gusting winds and ultimately capture all those precious moments in your heart so that you can cherish them forever. Our 17 days Upper Mustang Trek begins with a flight from the scenic lake city of Pokhara to Jomsom. From that point onward, you visibly make an effort to go through Mustang’s windswept mountain desert areas with our vigilant trekking staffs as planned in our trek itinerary. -

Culture, Capital, and Community in Mustang, Nepal

A Tale of Two Temples: Culture, Capital, and Community in Mustang, Nepal Sienna Craig Introduction This article focuses on two religious and community institutions. The first, Thubchen Lhakhang, is a 15th century temple located in the remote walled city of Lo Monthang, Mustang District, Nepal. The other, located near Swayambunath in the northwestern part of the Kathmandu Valley, is a newly built community temple meant to serve people from Mustang District. This paper asks why Thubchen has fallen into disrepair and disuse over the last decades, only to be “saved” by a team of foreign restoration experts, while the financial capital, sense of community, responsibility, and cultural commitment required, one could say, to “save” Thubchen by people from Mustang themselves has been invested instead in the founding of a new institution in Kathmandu. Through two narrative scenes and analysis, I examine who is responsible for a community’s sacred space, how each of the temples is being repaired or constructed, designed and administered, and the circumstances under which the temples are deemed finished. Finally, I comment on how these temples are currently being occupied and used, since restoration/construction efforts were completed. More generally, this paper speaks to anthropological concerns about local/global interfaces, particularly how the expectations and visions of cultural preservation, which often emanate from the west, impact and are impacted by communities and individuals such as those from Mustang. The circumstances surrounding these two projects illustrate larger questions about aesthetics and identity, agency, and transnational movements of people, resources, and ideas, as well as nostalgia for things “local” and “traditional” generated both by people from Mustang and their foreign interlocutors. -

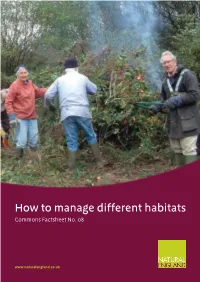

How to Manage Different Habitats Commons Factsheet No

How to manage different habitats Commons Factsheet No. 08 www.naturalengland.co.uk How to manage different habitats Many commons and greens are beautiful places, rich in wildlife. Because commons have a long history of being used by people, the habitats they support are relatively natural but have been shaped by human activities over the millennia (e.g. unimproved grassland, heathland, woodlands). If they are to retain their wildlife and scenery the traditional uses must either be continued, or replicated some other way (see FS3 Why does our common need to be looked after?). This factsheet summarises the characteristic features of each habitat type, together with conservation aims and management techniques for habitats frequently found on commons. Different techniques Before deciding on particular management techniques, you will want to consider their The management of habitats can vary from potential impact on the species present, simple to complex. It can often be carried the landscape, the environment, features out by volunteers with hand tools or may of archaeological and historical interest, need people with specialised training and and public access and safety (see FS5 Is our equipment. Here, the main methods you common more special than we think?, FS4 Who might use are outlined and sources of further has an interest in the common? and FS8 What information signposted. Herbicide treatments future for our commons?). Remember to plan are not discussed, as these are best used only aftercare and monitoring (see FS17 Are we if there are no other realistic options, and getting it right?). you will want specialist advice and possibly contractors to carry out the work. -

MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 Habitats * Semi-Natural Dry Grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210

Technical Report 2008 12/24 MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 habitats * Semi-natural dry grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210 The European Commission (DG ENV B2) commissioned the Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites) This document was prepared in March 2008 by Barbara Calaciura and Oliviero Spinelli, Comunità Ambiente Comments, data or general information were generously provided by: Bruna Comino, ERSAF Regione Lombardia, Italy Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Mats O.G. Eriksson, MK Natur- och Miljökonsult HB, Sweden Monika Janisova, Institute of Botany of Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovak Republic) Stefano Armiraglio, Museo di Scienze Naturali di Brescia, Italy Stefano Picchi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Guy Beaufoy, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Gwyn Jones, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Coordination: Concha Olmeda, ATECMA & Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente 2008 European Communities ISBN 978-92-79-08326-6 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Calaciura B & Spinelli O. 2008. Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites). European Commission This document, which has been prepared in the framework of a service contract (7030302/2006/453813/MAR/B2 "Natura 2000 preparatory actions: Management Models for Natura -

Localising Environment: Mustang's Struggle to Sustain Village Autonomy in Environmental Governance

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Localising environment: Mustang’s struggle to sustain village autonomy in environmental governance A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Lincoln University by Shailendra Bahadur Thakali Lincoln University 2012 ii Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of PhD. Localising environment: Mustang’s struggle to sustain village autonomy in environmental governance by Shailendra B. Thakali Decentralisation of environmental governance is a general trend worldwide and its emergence has largely coincided with a neo-liberal shift in policies for the management of environmental resources. Decentralisation is based on an assumption that the participation of the local people in natural resource management regimes will produce better long term outcomes for communities and their environment. There is little concrete evidence, however, on what transpires when local inhabitants are explicitly included in resource management planning and implementation, and more specifically, why and how the environment becomes their domain of concern in terms of environmental practices and beliefs. -

Bryn Tip Local Nature Reserve

BRYN TIP LOCAL NATURE RESERVE The village of Bryn is lucky enough to have its own Nature Reserve! The Reserve is popular with the residents of Bryn and visitors from further afield who come to walk their dogs, ride horses on the bridle way or take a gentle stroll whilst enjoying the wildlife and views of the surrounding countryside. The site has been used all year round and is also the starting point for the Bryn Heritage walk. This Reserve is home to hundreds of species of wildlife including flowers, fungi, invertebrates, birds, reptiles and mammals. The site was declared a Local Nature Reserve in order to protect the wildlife and preserve the landscape for people to enjoy long into the future. CONSERVATION GRAZING Over the last few years, the Countryside & Wildlife Team of the Local Authority have been working with contractors, and occasionally volunteers, to reduce the amount of invasive scrub on the site. This initial intensive management has allowed the grasses and flowering plants to flourish in those areas. However, unless the scrub is regularly managed it will become dense and eventually take over the grassland, making the site a lot less attractive to walk through. Similarly, the grassland is becoming rank and tussock and unless it is managed sensitively, much of the special wildlife will be lost. Using contractors and staff is not a sustainable long term approach for managing the Nature Reserve, even less so with the current and proposed budget cuts that the Local Authority is faced with. Conservation grazing is a more traditional, sustainable and less labour-intensive way of getting the grassland into good condition and keeping the scrub under control. -

Upper Mustang Trek Via Pokhara - 17 Days Langtang Ri Trekking & Expedition

Upper Mustang Trek via Pokhara - 17 Days Langtang Ri Trekking & Expedition Upper Mustang Trek via Pokhara - 17 Days The Mustang region of western Nepal is one of the country’s most recent districts to be opened for international visitors and trekkers. Until relatively recently it was the Kingdom of Lo and its people lived as part of the Tibetan Himalayan culture. Tibetan languages are still spoken there and the culture, practices and beliefs of the people are still strongly influenced by Tibet. While the Kingdom of Lo became part of Nepal in the late 18th century, the position of monarch, or king, was only abolished by the Government of Nepal in 2008. So the Mustang region offer visitors a glimpse into a unique cultural community of Nepal in a stunning high Himalayan desert landscape. The Upper Mustang region essentially represents the catchment area of the Kali Gandaki River as it drains southward from the high mountains along the border between Tibet and Nepal. The river valley provides the only access to the region and transport is usually by foot with pack horses used for heavy loads, however some “treks” are conducted on mountain bikes. The region is located in the rain shadow of the Annapurna Massif and the high ranges that buttress 8,172m high Mount Dhaulagiri 1. These mountain ranges block much of the annual monsoon rains that sweep northward across India. As a result the Upper Mustang region is a desert landscape of bare rocky mountains and dry river beds. But even in these challenging conditions the people of Upper Mustang have lived well on the back of their well managed farming plots, livestock grazing and the traditional industry of exporting Himalayan mountain salt blocks down the dusty trails of the Kali Gandaki River.