Furthering Perspectives Vol 2.Pdf (2.360Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Painless Peace of Twilight Sleep Cheryl Miller

2 2 The Painless Peace of Twilight Sleep Cheryl Miller hen Aldous Huxley’s Upon its publication, Wharton had Brave New World was been attacked as being out of touch Wfirst published seventy- with American life (she had spent five years ago, the critical reception only eleven days in her native coun- was markedly unenthusiastic—but try since 1913), and accused of sell- it did find one appreciative reader. ing out. In the Boston Transcript, Edith Wharton, then in her seventies Dorothy Gillman wrote, “The result and living abroad in France, was not of deserting her own class is disas- a fan of the new generation of writers trous for Mrs. Wharton. She now (she detested Joyce as “pornographic,” adventures in a world which she and thought Virginia Woolf’s novels does not really know...she seems works of pure “exhibitionism”). But deliberately to set out to write a com- in Brave New World, she found a work monplace story that will delight and that spoke to many of her own res- entertain readers of serialized fic- ervations about the modern age. She tion.” Frederick Hoffman concurred, praised it as a “tragic indictment of claiming Wharton seemed “insulted our ghastly age of Fordian culture” by history,” while Carl Van Vechten, and “un chef-d’oeuvre digne de Swift” writing in The Nation, called the (“a masterpiece worthy of Swift”). “I new work, “scrupulous, clever, and suffer from a complete inability to uninspired.” read novels about a future state of Eighty years later, the novel society,” she wrote one friend, “but in remains little-read. -

Pós-Graduação Em Letras-Inglês Social Critique in Scorsese's the Age of Innocence and Madden's Ethan Frome: Filmic Adaptat

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS-INGLÊS SOCIAL CRITIQUE IN SCORSESE'S THE AGE OF INNOCENCE AND MADDEN'S ETHAN FROME: FILMIC ADAPTATIONS OF TWO NOVELS BY EDITH WHARTON por HELEN MARIA LINDEN Dissertação submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS FLORIANÓPOLIS Novembro, 1996 Esta Dissertação foi julgada adequada e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Inglês para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS Opção Literatura Jos Roberto O'Shea OORDENÀDOR Anelise Reich Corseuil ORIENTADORA BANCA EXAMINADORA: Anelise Reich Corseuil Bernadete Pasold Florianópolis, 28 de novembro de 1996. Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM INGLÊS of the UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA, in special Dr. Anelise Reich Corseuil, my advisor, for the academic support and friendship. Besides the professors that have, in one way or another, enabled me to write this dissertation. Dr. Bernadete Pasold deserves special thanks for her interest in reading and discussing specific parts of my study. Dr. Sara Kozloff, from Vassar College, also devoted some time in reading part of my dissertation and providing interesting suggestions. I am grateful for her interest and contribuitions. I could not exclude Professor John Caughie, from Glasgow University, whose important insights for my research were given during his stay in Florianópolis. I would also like to thank CNPq for the financial support which enabled me to develop this research. I am very grateful to my friend and colleague Viviane Heberle whose invitation to enter the program was the starting point of my return to the academic life. -

Men's Collection

Men’s Collection 1 Lovers’ Rings A romantic pair of rings featuring GIA Certified Natural Fancy Dark Orangy Brown Diamonds. Smaller natural color diamonds form half a heart on each side crossing on the inside of the shank. The rings are completed with a yellow gold heart insert. GIA Certified Natural Fancy Dark Orangy Brown Diamond (3.17 ct) ring. Natural mixed-color diamond melee, platinum, 18K yellow gold. Size 10.5. GIA Certified Natural Fancy Dark Orangy Brown Diamond (2.51 ct) ring. Natural mixed-color diamond melee, platinum, 18K yellow gold. Size 9. 2 3 Pasha Ring A very mysterious brooch that seems to glow and come to life in subdued light. A genie, a sultan or an empress would wear this spectacular over-sized, seriously sensuous art ring. A truly magnificent piece of sculpture you An 18k white gold petal brooch set with approximately 675 stones can wear. This one-of-a-kind ring features a hand-carved 63.5 ct smoky consisting of VS-FG white diamonds, olive diamonds, brown dia- quartz set in platinum, 18K yellow gold, and 18k white gold with 1.17 ct monds yellow diamonds, pink diamonds, amethysts, multicolored of VS-F-G white diamonds. It fits high up on the hand and is designed sapphires and finished with an elaborate back detail signature grill. specifically to fit comfortably. 4 5 Hand-carved nephrite jade brooches with VS-FG white diamonds, Three beautiful 18k yellow gold hand-carved Australian chrysoprase 18K yellow gold and blackened sterling silver. brooches set with VS-FG white diamonds. -

Use & Care Guide Ruby Series Grill by Sunstone®

RUBY SERIES GRILL BY SUNSTONE® USE & CARE GUIDE Read all instructions before you operate your grill. Save these instructions! Conforms to ANSI STD Z21.58b-2012 Certified to CSA STD 1.6b-2012 Outdoor Cooking Gas Appliance 3174816 To installer or person assembling grill: Leave this manual with grill for future reference. To consumer: Keep this manual for future reference. www.sunstonemetalproducts.com ATTENTION: THE RUBY GRILL MUST BE INSTALLED ACCORDING TO THE INSTALLATION GUIDE SHOWN ON PAGES 9 THRU 14. IF YOUR GRILL INSTALLATION DOES NOT MEET THE BASIC SETUP INSTRUCTIONS ALL WARRANTIES MAY BE VOID. SEE WARRANTY ON LAST PAGE. Welcome & Congratulations Congratulations on your purchase of a new Ruby grill! We are very proud of our product and we are completely committed to providing you with the best service possible. Your satisfaction is our #1 priority. Please read this manual carefully to understand all the instructions about how to install, operate and maintain for optimum performance and longevity. We know you’ll enjoy your new grill and thank you for choosing our product. We hope you consider us for future purchases. How to Obtain Service Before you call Is there Gas supplied to the Grill? Have you recently refilled the LP Tank? Please make sure you have the following information: MODEL NUMBER | DATE OF PURCHASE| INVOICE NUMBER. KEEP A COPY OF THE GRILLS ITEMIZED INVOICE FOR YOUR RECORDS For warranty service, contact SUNSTONE Customer Service Department at (888)-934-9449 or email [email protected]. SUNSTONE METAL PRODUCTS LLC. 16004 Central Commerce Dr, Pflugerville Texas 78660. Business Hours. -

Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina by W

.'.' .., Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie RUTILE GUMMITE IN GARNET RUBY CORUNDUM GOLD TORBERNITE GARNET IN MICA ANATASE RUTILE AJTUNITE AND TORBERNITE THULITE AND PYRITE MONAZITE EMERALD CUPRITE SMOKY QUARTZ ZIRCON TORBERNITE ~/ UBRAR'l USE ONLV ,~O NOT REMOVE. fROM LIBRARY N. C. GEOLOGICAL SUHVEY Information Circular 24 Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie Raleigh 1978 Second Printing 1980. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: North CarOlina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development Geological Survey Section P. O. Box 27687 ~ Raleigh. N. C. 27611 1823 --~- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SECTION The Geological Survey Section shall, by law"...make such exami nation, survey, and mapping of the geology, mineralogy, and topo graphy of the state, including their industrial and economic utilization as it may consider necessary." In carrying out its duties under this law, the section promotes the wise conservation and use of mineral resources by industry, commerce, agriculture, and other governmental agencies for the general welfare of the citizens of North Carolina. The Section conducts a number of basic and applied research projects in environmental resource planning, mineral resource explora tion, mineral statistics, and systematic geologic mapping. Services constitute a major portion ofthe Sections's activities and include identi fying rock and mineral samples submitted by the citizens of the state and providing consulting services and specially prepared reports to other agencies that require geological information. The Geological Survey Section publishes results of research in a series of Bulletins, Economic Papers, Information Circulars, Educa tional Series, Geologic Maps, and Special Publications. -

Treasures of Middle Earth

T M TREASURES OF MIDDLE-EARTH CONTENTS FOREWORD 5.0 CREATORS..............................................................................105 5.1 Eru and the Ainur.............................................................. 105 PART ONE 5.11 The Valar.....................................................................105 1.0 INTRODUCTION........................................................................ 2 5.12 The Maiar....................................................................106 2.0 USING TREASURES OF MIDDLE EARTH............................ 2 5.13 The Istari .....................................................................106 5.2 The Free Peoples ...............................................................107 3.0 GUIDELINES................................................................................ 3 5.21 Dwarves ...................................................................... 107 3.1 Abbreviations........................................................................ 3 5.22 Elves ............................................................................ 109 3.2 Definitions.............................................................................. 3 5.23 Ents .............................................................................. 111 3.3 Converting Statistics ............................................................ 4 5.24 Hobbits........................................................................ 111 3.31 Converting Hits and Bonuses...................................... 4 5.25 -

Rockhounding North America

ROCKHOUNDING NORTH AMERICA Compiled by Shelley Gibbins Photos by Stefan and Shelley Gibbins California Sapphires — Montana *Please note that the Calgary Rock and Lapidary Quartz — Montana Club is not advertising / sponsoring these venues, but sharing places for all rock lovers. *Also, remember that rules can change; please check that these venues are still viable and permissible options before you go. *There is some risk in rockhounding, and preventative measures should be taken to avoid injury. The Calgary Rock and Lapidary Club takes no responsibility for any injuries should they occur. *I have also included some locations of interest, which are not for collecting Shells — Utah General Rules for Rockhounding (keep in mind that these may vary from place to place) ! • Rockhounding is allowed on government owned land (Crown Land in Canada and Bureau of Land Management in USA) ! • You can collect on private property only with the permission of the landowner ! • Collecting is not allowed in provincial or national parks ! • The banks along the rivers up to the high water mark may be rock hounded ! • Gold panning may or may not need a permit – in Alberta you can hand pan, but need a permit for sluice boxes ! • Alberta fossils are provincial property and can generally not be sold – you can surface collect but not dig. You are considered to be the temporary custodian and they need to stay within the province Fossilized Oysters — BC Canada ! Geology of Provinces ! Government of Canada. Natural resources Canada. (2012). Retrieved February 6/14 from http://atlas.gc.ca/site/ english/maps/geology.html#rocks. -

Healing Gemstones for Everyday Use

GUIDE TO THE WORLD’S TOP 20 MOST EFFECTIVE HEALING GEMSTONES FOR EVERYDAY USE BY ISABELLE MORTON Guide to the World’s Top 20 Most Effective Healing Gemstones for Everyday Use Copyright © 2019 by Isabelle Morton Photography by Ryan Morton, Isabelle Morton Cover photo by Jeff Skeirik All rights reserved. Published by The Gemstone Therapy Institute P.O. Box 4065 Manchester, Connecticut 06045 U.S.A. www.GemstoneTherapyInstitute.org IMPORTANT NOTICE This book is designed to provide information for purposes of reference and guidance and to accompany, not replace, the services of a qualified health care practitioner or physician. It is not the intent of the author or publisher to prescribe any substance or method to cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent any disease. In the event that you use this information with or without seeking medical attention, the author and publisher shall not be liable or otherwise responsible for any loss, damage, or injury directly or indirectly caused by or arising out of the information contained herein. CONTENTS Gemstones for Physical Healing Light Green Aventurine 5 Dark Green Aventurine 11 Malachite 17 Tree Agate 23 Gemstones for Emotional Healing Rhodonite 30 Morganite 36 Pink Chalcedony 43 Rose Quartz 49 Gemstones for Healing Memory, Patterns, & Habits Opalite 56 Leopardskin Jasper 62 Golden Beryl 68 Rhodocrosite 74 Gemstones for Healing the Mental Body Sodalite 81 Blue Lace Agate 87 Lapis Lazuli 93 Lavender Quartz 99 Gemstones to Nourish Your Spirit Amethyst 106 Clear Quartz / Frosted Quartz 112 Mother of Pearl 118 Gemstones For Physical Healing LIGHT GREEN AVENTURINE DARK GREEN AVENTURINE MALACHITE TREE AGATE https://GemstoneTherapyInstitute.org LIGHT GREEN AVENTURINE 5 Copyright © 2019 Isabelle Morton. -

“TO GO on DOING BABBITTS”: RECONTEXTUALIZING TWILIGHT SLEEP AS LEWISIAN SATIRE by SARAH JEANNE SCHAITKIN a Thesis Submitted

“TO GO ON DOING BABBITTS”: RECONTEXTUALIZING TWILIGHT SLEEP AS LEWISIAN SATIRE BY SARAH JEANNE SCHAITKIN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December 2013 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Barry Maine, Ph.D., Advisor Erica Still, Ph.D., Chair Rian Bowie, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are so many people to whom I owe my sincerest gratitude, for without their support I would not have been able to undertake this project and complete this degree. First and foremost, I would like to thank my dad for his constant support, encouragement, and love. Without his upbeat texts and calls I would long since have given up. Thank you to Tom Lambert, for loving me, believing in me, and taking a genuine interest in my work. Thank you to my advisor, Barry Maine, for giving me both constructive feedback and the space to work independently. Thank you to my friends and family for keeping me abreast of happenings outside my own work-bubble and for listening to me as I doubted myself and hit my limit. Thank you to Nicole Fitzpatrick for being my escape from work and for rarely saying no to takeout. A special thank you to my roommate and constant companion, Katie Williams, for being both my playmate and academic confidante. I shudder to think about what this process would have been like without you (and our signature snack—pizza rolls). ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT. -

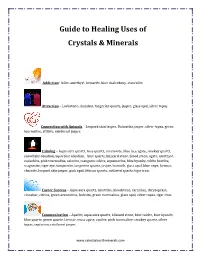

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals Addiction- Iolite, amethyst, hematite, blue chalcedony, staurolite. Attraction – Lodestone, cinnabar, tangerine quartz, jasper, glass opal, silver topaz. Connection with Animals – Leopard skin Jasper, Dalmatian jasper, silver topaz, green tourmaline, stilbite, rainforest jasper. Calming – Aqua aura quartz, rose quartz, amazonite, blue lace agate, smokey quartz, snowflake obsidian, aqua blue obsidian, blue quartz, blizzard stone, blood stone, agate, amethyst, malachite, pink tourmaline, selenite, mangano calcite, aquamarine, blue kyanite, white howlite, magnesite, tiger eye, turquonite, tangerine quartz, jasper, bismuth, glass opal, blue onyx, larimar, charoite, leopard skin jasper, pink opal, lithium quartz, rutilated quartz, tiger iron. Career Success – Aqua aura quartz, ametrine, bloodstone, carnelian, chrysoprase, cinnabar, citrine, green aventurine, fuchsite, green tourmaline, glass opal, silver topaz, tiger iron. Communication – Apatite, aqua aura quartz, blizzard stone, blue calcite, blue kyanite, blue quartz, green quartz, larimar, moss agate, opalite, pink tourmaline, smokey quartz, silver topaz, septarian, rainforest jasper. www.celestialearthminerals.com Creativity – Ametrine, azurite, agatized coral, chiastolite, chrysocolla, black amethyst, carnelian, fluorite, green aventurine, fire agate, moonstone, celestite, black obsidian, sodalite, cat’s eye, larimar, rhodochrosite, magnesite, orange calcite, ruby, pink opal, blue chalcedony, abalone shell, silver topaz, green tourmaline, -

Interpreting Unhappy Women in Edith Wharton's Novels Min-Jung Lee

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Interpreting Unhappy Women in Edith Wharton's Novels Min-Jung Lee Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES INTERPRETING UNHAPPY WOMEN IN EDITH WHARTON‟S NOVELS BY MIN-JUNG LEE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Min-Jung Lee defended on October 29, 2008. ____________________________ Dennis Moore Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________ Jennifer Koslow Outside Committee ____________________________ Ralph Berry Committee Member ____________________________ Jerrilyn McGregory Committee Member Approved: Ralph Berry, Chair, Department of English ii ACKNOWLEGMENTS I embarked on writing this dissertation with fear, excitement, and a realization of the discipline that was going to be needed. While there were difficulties and mistakes made along the way, there are many people whose help has been instrumental. Without the support and guidance of my major professor, Dennis Moore, completion of this dissertation would not be possible. I will always be indebted for his keen insight into my project. Prof. Ralph Berry provided a critical eye and also a generous heart during the early stage of this work and challenged me to make this project worthwhile. He was always aware of my weaknesses and strengths and guided me in making this dissertation into the one that I wanted it to be. I am also very grateful for the commentary and the warm heart of Prof. -

Volume 35 / No. 7 / 2017

GemmologyThe Journal of Volume 35 / No. 7 / 2017 The Gemmological Association of Great Britain Contents GemmologyThe Journal of Volume 35 / No. 7 / 2017 COLUMNS p. 581 569 What’s New AMS2 melee diamond tester| p. 586 MiNi photography system| Spectra diamond colorimeter| Lab Information Circular| Gemmological Society of Japan abstracts|Bead-cultured blister pearls from Pinctada maculata|Rubies from Cambo- dia and Thailand|Goldsmiths’ S. Bruce-Lockhart photo Review|Topaz and synthetic moissanite imitating rough diamonds|Santa Fe Symposium proceedings|Colour-change ARTICLES glass imitating garnet rough| Thanh Nhan Bui photo M2M diamond-origin tracking service|More historical reading Feature Articles lists 598 The Linkage Between Garnets Found in India at the 572 Gem Notes Arikamedu Archaeological Site and Their Source at Cat’s-eye aquamarine from Meru, the Garibpet Deposit Kenya|Colour-zoned beryl from By Karl Schmetzer, H. Albert Gilg, Ulrich Schüssler, Jayshree Pakistan|Coloration of green dravite from Tanzania|Enstatite Panjikar, Thomas Calligaro and Patrick Périn from Emali, Kenya|Grossular from Tanga, Tanzania|Natrolite 628 Simultaneous X-Radiography, Phase-Contrast from Portugal|Large matrix opal and Darkfield Imaging to Separate Natural from carving|Sapphires from Tigray, Cultured Pearls northern Ethiopia|Whewellite from the Czech Republic| By Michael S. Krzemnicki, Carina S. Hanser and Vincent Revol Inclusions in sunstone feldspar from Norway and topaz from Sri 640 Camels, Courts and Financing the French Blue Lanka|Quartz with a tourmaline