Guide to the Nomenclature of Particle Dispersion Technology for Ceramic Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Decays of the Tau Lepton*

SLAC - 292 UC - 34D (E) DECAYS OF THE TAU LEPTON* Patricia R. Burchat Stanford Linear Accelerator Center Stanford University Stanford, California 94305 February 1986 Prepared for the Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC03-76SF00515 Printed in the United States of America. Available from the National Techni- cal Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161. Price: Printed Copy A07, Microfiche AOl. JC Ph.D. Dissertation. Abstract Previous measurements of the branching fractions of the tau lepton result in a discrepancy between the inclusive branching fraction and the sum of the exclusive branching fractions to final states containing one charged particle. The sum of the exclusive branching fractions is significantly smaller than the inclusive branching fraction. In this analysis, the branching fractions for all the major decay modes are measured simultaneously with the sum of the branching fractions constrained to be one. The branching fractions are measured using an unbiased sample of tau decays, with little background, selected from 207 pb-l of data accumulated with the Mark II detector at the PEP e+e- storage ring. The sample is selected using the decay products of one member of the r+~- pair produced in e+e- annihilation to identify the event and then including the opposite member of the pair in the sample. The sample is divided into subgroups according to charged and neutral particle multiplicity, and charged particle identification. The branching fractions are simultaneously measured using an unfold technique and a maximum likelihood fit. The results of this analysis indicate that the discrepancy found in previous experiments is possibly due to two sources. -

Assessment of the Use of Dispersants on Oil Spills in California Marine Waters

Assessment of the Use of Dispersants on Oil Spills in California Marine Waters by S.L. Ross Environmental Research Ltd. 200-717 Belfast Rd. Ottawa, ON K1G 0Z4 for Minerals Management Service Engineering and Research Branch 381 Elden Street Herndon, VA 20170-4817 June 2002 Summary Objective This project is a comprehensive assessment of operational and environmental factors associated with using chemical dispersants to treat oil spills in California. The project addresses spills from both transportation and production sources. It addresses four subjects: a) amenability of produced and imported oils to chemical dispersion; b) time windows (TW) for chemical dispersion in California spills; c) operational logistic and feasibility issues in California; and d) net environmental benefits or drawbacks of dispersant use for California spills. Review of Basics The report begins with a review of the basics of (a) marine spill behavior, (b) chemical dispersants, (c) factors that control dispersant effectiveness, and (d) accounts of field trials and spills. The review shows that dispersants will be effective if: (a) the response takes place quickly while the spilled oil is unemulsified, relatively thick, and low in viscosity; (b) the thick portions of the spill are treated with state-of-the art chemicals at the proper dose; and (c) sea states are light-to-medium or greater. If the spilled oil becomes highly viscous through the process of water-in-oil emulsification, dispersant use will not be effective. Likely Dispersibility of California Oils Three groups of oils are considered: a) crude oils produced in California OCS waters; b) oils imported into California ports; and c) fuel oils spilled from marine industrial activities (e.g., fuel tanks from ships, cargoes of small tankers). -

Chemical Dispersants and Their Role in Oil Spill

THE SEA GRANT and GOMRI CHEMICAL DISPERSANTS AND THEIR PARTNERSHIP ROLE IN OIL SPILL RESPONSE The mission of Sea Grant is to enhance the practical use and Larissa J. Graham, Christine Hale, Emily Maung-Douglass, Stephen Sempier, conservation of coastal, marine LaDon Swann, and Monica Wilson and Great Lakes resources in order to create a sustainable economy and environment. Nearly two million gallons of dispersants were used at the water’s There are 33 university–based surface and a mile below the surface to combat oil during the Sea Grant programs throughout the coastal U.S. These programs Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Many Gulf Coast residents have questions are primarily supported by about why dispersants were used, how they were used, and what the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration impacts dispersants could have on people and the environment. and the states in which the programs are located. In the immediate aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP committed $500 million over a 10–year period to create the Gulf of Mexico Research Institute, or GoMRI. It is an independent research program that studies the effect of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as develops improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. GoMRI is led by an independent and academic 20–member research board. The Sea Grant oil spill science outreach team identifies the best available science from The Deepwater Horizon site (NOAA photo) projects funded by GoMRI and others, and only shares peer- reviewed research results. On April 20, 2010, an explosion on million barrels (172 million gallons), were the Deepwater Horizon oil rig killed released into Gulf of Mexico waters.1,2,3,4,5 11 people. -

Mechanical Dispersion of Clay from Soil Into Water: Readily-Dispersed and Spontaneously-Dispersed Clay Ewa A

Int. Agrophys., 2015, 29, 31-37 doi: 10.1515/intag-2015-0007 Mechanical dispersion of clay from soil into water: readily-dispersed and spontaneously-dispersed clay Ewa A. Czyż1,2* and Anthony R. Dexter2 1Department of Soil Science, Environmental Chemistry and Hydrology, University of Rzeszów, Zelwerowicza 8b, 35-601 Rzeszów, Poland 2Institute of Soil Science and Plant Cultivation (IUNG-PIB), Czartoryskich 8, 24-100 Puławy, Poland Received July 1, 2014; accepted October 10, 2014 A b s t r a c t. A method for the experimental determination of Clay particles can either flocculate or disperse in aque- the amount of clay dispersed from soil into water is described. The ous solution. When flocculation occurs, the particles com- method was evaluated using soil samples from agricultural fields bine to form larger, compound particles such as soil in 18 locations in Poland. Soil particle size distributions, contents microaggregates. When dispersion occurs, the particles of organic matter and exchangeable cations were measured by separate in suspension due to their electrical charge. Clay standard methods. Sub-samples were placed in distilled water flocculation leads to soils that are considered to be stable in wa- and were subjected to four different energy inputs obtained by ter whereas dispersion is associated with soils that are consi- different numbers of inversions (end-over-end movements). The dered to be unstable in water. We may note that this termi- amounts of clay that dispersed into suspension were measured by light scattering (turbidimetry). An empirical equation was devel- nology is the opposite of that used in colloid science where oped that provided an approximate fit to the experimental data for the terms ‘stable’ and ‘unstable’ are used in relation to the turbidity as a function of number of inversions. -

Colloidal Suspensions

Chapter 9 Colloidal suspensions 9.1 Introduction So far we have discussed the motion of one single Brownian particle in a surrounding fluid and eventually in an extaernal potential. There are many practical applications of colloidal suspensions where several interacting Brownian particles are dissolved in a fluid. Colloid science has a long history startying with the observations by Robert Brown in 1828. The colloidal state was identified by Thomas Graham in 1861. In the first decade of last century studies of colloids played a central role in the development of statistical physics. The experiments of Perrin 1910, combined with Einstein's theory of Brownian motion from 1905, not only provided a determination of Avogadro's number but also laid to rest remaining doubts about the molecular composition of matter. An important event in the development of a quantitative description of colloidal systems was the derivation of effective pair potentials of charged colloidal particles. Much subsequent work, largely in the domain of chemistry, dealt with the stability of charged colloids and their aggregation under the influence of van der Waals attractions when the Coulombic repulsion is screened strongly by the addition of electrolyte. Synthetic colloidal spheres were first made in the 1940's. In the last twenty years the availability of several such reasonably well characterised "model" colloidal systems has attracted physicists to the field once more. The study, both theoretical and experimental, of the structure and dynamics of colloidal suspensions is now a vigorous and growing subject which spans chemistry, chemical engineering and physics. A colloidal dispersion is a heterogeneous system in which particles of solid or droplets of liquid are dispersed in a liquid medium. -

Charged Particle Radiotherapy

Corporate Medical Policy Charged Particle Radiotherapy File Name: charged_particle_radiotherapy Origination: 3/12/96 Last CAP Review: 5/2021 Next CAP Review: 5/2022 Last Review: 5/2021 Description of Procedure or Service Cha rged-particle beams consisting of protons or helium ions or carbon ions are a type of particulate ra dia tion therapy (RT). They contrast with conventional electromagnetic (i.e., photon) ra diation therapy due to several unique properties including minimal scatter as particulate beams pass through tissue, and deposition of ionizing energy at precise depths (i.e., the Bragg peak). Thus, radiation exposure of surrounding normal tissues is minimized. The theoretical advantages of protons and other charged-particle beams may improve outcomes when the following conditions a pply: • Conventional treatment modalities do not provide adequate local tumor control; • Evidence shows that local tumor response depends on the dose of radiation delivered; and • Delivery of adequate radiation doses to the tumor is limited by the proximity of vital ra diosensitive tissues or structures. The use of proton or helium ion radiation therapy has been investigated in two general categories of tumors/abnormalities. However, advances in photon-based radiation therapy (RT) such as 3-D conformal RT, intensity-modulated RT (IMRT), a nd stereotactic body ra diotherapy (SBRT) a llow improved targeting of conventional therapy. 1. Tumors located near vital structures, such as intracranial lesions or lesions a long the a xial skeleton, such that complete surgical excision or adequate doses of conventional radiation therapy are impossible. These tumors/lesions include uveal melanomas, chordomas, and chondrosarcomas at the base of the skull and a long the axial skeleton. -

Dispersant Additives and Additive Concentrates and Lubricating Oil Compositions Containing Same

(19) TZZ¥_ __T (11) EP 3 124 581 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 01.02.2017 Bulletin 2017/05 C10M 163/00 (2006.01) C10M 169/04 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 16179973.9 (22) Date of filing: 18.07.2016 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Oberoi, Sonia AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Linden, NJ New Jersey 07036 (US) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO • Hu, Gang PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR Linden, NJ New Jersey 07036 (US) Designated Extension States: •HOBIN,Peter BA ME Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX13 6BB (GB) Designated Validation States: • STRANGE, Gareth MA MD Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX13 6BB (GB) • CATANI, Alessandra (30) Priority: 30.07.2015 US 201514813257 17047 Savona - Liguria (IT) • FITTER, Claire (71) Applicant: Infineum International Limited Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX13 6BB (GB) Abingdon, • MILLINGTON, James Oxfordshire OX13 6BB (GB) Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX13 6BB (GB) (72) Inventors: (74) Representative: Goddard, Frances Anna et al • Emert, Jacob PO Box 1 Linden, NJ New Jersey 07036 (US) Milton Hill Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX13 6BB (GB) (54) DISPERSANT ADDITIVES AND ADDITIVE CONCENTRATES AND LUBRICATING OIL COMPOSITIONS CONTAINING SAME (57) A lubricant additive concentrate having a kine- cinic anhydride (SA) functionality (F) of greater than 1.7 matic viscosity of from about 40 to about 300 cSt at and less than about 2.5; and a detergent colloid including 100°C,containing a dispersant-detergent colloid mixture, overbased detergent having a total base number (TBN) including -

Additive Components

Performance you can rely on. Additive Components InfineumInsight.com/Learn © INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2017. All Rights Reserved. 2015006e . © INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2017. All Rights Reserved. 2015006e . Performance you can rely on. What happens without lubrication? © INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2017. All Rights Reserved. 2015006e . Performance you can rely on. Outline • The function of additives – What do they do? • Destructive processes in the engine – What are these processes? – How do additives minimize them? • Types of additives – Which additives are commonly used? – How do they work? © INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2017. All Rights Reserved. 2015006e . Performance you can rely on. The function of additives Why do we add additives? – Enhance lubricant performance – Minimise destructive processes in the engine – Extend oil life time © INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2017. All Rights Reserved. 2015006e . Performance you can rely on. Destructive processes in the engine What destructive process are present in the engine? • Mechanical – Wear of engine parts – Shear affecting lubricant properties • Chemical – Corrosion of engine parts – Oxidation of lubricant © INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2017. All Rights Reserved. 2015006e . Performance you can rely on. Destructive processes in the engine Friction and wear • Both are caused by relative motion between surfaces • Friction is the loss of energy – dissipated as heat – Types – sliding, rolling, static on i t c • Wear is loss of material i r – Types – abrasion, adhesion, -

The Basic Interactions Between Photons and Charged Particles With

Outline Chapter 6 The Basic Interactions between • Photon interactions Photons and Charged Particles – Photoelectric effect – Compton scattering with Matter – Pair productions Radiation Dosimetry I – Coherent scattering • Charged particle interactions – Stopping power and range Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The – Bremsstrahlung interaction th physics of radiology, 4 ed. – Bragg peak http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Photon interactions Photoelectric effect • Collision between a photon and an • With energy deposition atom results in ejection of a bound – Photoelectric effect electron – Compton scattering • The photon disappears and is replaced by an electron ejected from the atom • No energy deposition in classical Thomson treatment with kinetic energy KE = hν − Eb – Pair production (above the threshold of 1.02 MeV) • Highest probability if the photon – Photo-nuclear interactions for higher energies energy is just above the binding energy (above 10 MeV) of the electron (absorption edge) • Additional energy may be deposited • Without energy deposition locally by Auger electrons and/or – Coherent scattering Photoelectric mass attenuation coefficients fluorescence photons of lead and soft tissue as a function of photon energy. K and L-absorption edges are shown for lead Thomson scattering Photoelectric effect (classical treatment) • Electron tends to be ejected • Elastic scattering of photon (EM wave) on free electron o at 90 for low energy • Electron is accelerated by EM wave and radiates a wave photons, and approaching • No -

Known As the Dispersed Phase), Distributed Throughout a Continuous Phase (Known As Dispersion Medium)

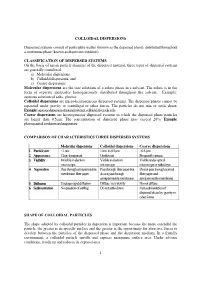

COLLOIDAL DISPERSIONS Dispersed systems consist of particulate matter (known as the dispersed phase), distributed throughout a continuous phase (known as dispersion medium). CLASSIFICATION OF DISPERSED SYSTEMS On the basis of mean particle diameter of the dispersed material, three types of dispersed systems are generally considered: a) Molecular dispersions b) Colloidal dispersions, and c) Coarse dispersions Molecular dispersions are the true solutions of a solute phase in a solvent. The solute is in the form of separate molecules homogeneously distributed throughout the solvent. Example: aqueous solution of salts, glucose Colloidal dispersions are micro-heterogeneous dispersed systems. The dispersed phases cannot be separated under gravity or centrifugal or other forces. The particles do not mix or settle down. Example: aqueous dispersion of natural polymer, colloidal silver sols, jelly Coarse dispersions are heterogeneous dispersed systems in which the dispersed phase particles are larger than 0.5µm. The concentration of dispersed phase may exceed 20%. Example: pharmaceutical emulsions and suspensions COMPARISON OF CHARACTERISTICS THREE DISPERSED SYSTEMS Molecular dispersions Colloidal dispersions Coarse dispersions 1. Particle size <1 nm 1 nm to 0.5 µm >0.5 µm 2. Appearance Clear, transparent Opalescent Frequently opaque 3. Visibility Invisible in electron Visible in electron Visible under optical microscope microscope microscope or naked eye 4. Separation Pass through semipermeable Pass through filter paper but Do not pass through -

CHAPTER 3 Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution

CHAPTER 3 Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution Lesson Goal Demonstrate an understanding of the meteorological factors that influence wind and turbulence, the relationship of air current stability, and the effect of each of these factors on air pollution transport and dispersion; understand the role of topography and its influence on air pollution, by successfully completing the review questions at the end of the chapter. Lesson Objectives 1. Describe the various methods of air pollution transport and dispersion. 2. Explain how dispersion modeling is used in Air Quality Management (AQM). 3. Identify the four major meteorological factors that affect pollution dispersion. 4. Identify three types of atmospheric stability. 5. Distinguish between two types of turbulence and indicate the cause of each. 6. Identify the four types of topographical features that commonly affect pollutant dispersion. Recommended Reading: Godish, Thad, “The Atmosphere,” “Atmospheric Pollutants,” “Dispersion,” and “Atmospheric Effects,” Air Quality, 3rd Edition, New York: Lewis, 1997, pp. 1-22, 23-70, 71-92, and 93-136. Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution References Bowne, N.E., “Atmospheric Dispersion,” S. Calvert and H. Englund (Eds.), Handbook of Air Pollution Technology, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1984, pp. 859-893. Briggs, G.A. Plume Rise, Washington, D.C.: AEC Critical Review Series, 1969. Byers, H.R., General Meteorology, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1956. Dobbins, R.A., Atmospheric Motion and Air Pollution, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979. Donn, W.L., Meteorology, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1975. Godish, Thad, Air Quality, New York: Academic Press, 1997, p. 72. Hewson, E. Wendell, “Meteorological Measurements,” A.C.