Gaming and the Arts of Storytelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balance Sheet Also Improves the Company’S Already Strong Position When Negotiating Publishing Contracts

Remedy Entertainment Extensive report 4/2021 Atte Riikola +358 44 593 4500 [email protected] Inderes Corporate customer This report is a summary translation of the report “Kasvupelissä on vielä monta tasoa pelattavana” published on 04/08/2021 at 07:42 Remedy Extensive report 04/08/2021 at 07:40 Recommendation Several playable levels in the growth game R isk Accumulate Buy We reiterate our Accumulate recommendation and EUR 50.0 target price for Remedy. In 2019-2020, Remedy’s (previous Accumulate) strategy moved to a growth stage thanks to a successful ramp-up of a multi-project model and the Control game Accumulate launch, and in the new 2021-2025 strategy period the company plans to accelerate. Thanks to a multi-project model EUR 50.00 Reduce that has been built with controlled risks and is well-managed, as well as a strong financial position, Remedy’s (previous EUR 50.00) Sell preconditions for developing successful games are good. In addition, favorable market trends help the company grow Share price: Recommendation into a clearly larger game studio than currently over this decade. Due to the strongly progressing growth story we play 43.75 the long game when it comes to share valuation. High Low Video game company for a long-term portfolio Today, Remedy is a purebred profitable growth company. In 2017-2018, the company built the basis for its strategy and the successful ramp-up of the multi-project model has been visible in numbers since 2019 as strong earnings growth. In Key indicators 2020, Remedy’s revenue grew by 30% to EUR 41.1 million and the EBIT margin was 32%. -

Alien: Isolation™ Coming to Nintendo Switch

Alien: Isolation™ coming to Nintendo Switch DATE: Wednesday, June 12th, 2019 CONTACT: Mary Musgrave at [email protected] Feral Interactive today announced that Alien: Isolation, the AAA survival horror game, is coming to Nintendo Switch. Originally developed by Creative Assembly and published by SEGA, Alien: Isolation won multiple awards, and was critically acclaimed for its tense, atmospheric gameplay and fidelity to the production values of the iconic 20th Century Fox film, Alien. In an original story set fifteen years after the events of the film, players take on the role of Ellen Ripley’s daughter Amanda, who seeks to discover the truth behind her mother’s disappearance. Marooned aboard the remote space station Sevastopol with a few desperate survivors, players must stay out of sight, and use their wits to survive as they are stalked by the ever-present, unstoppable Alien. Sevastopol Station is a labyrinthine environment that contains hundreds of hidden items that provide clues to the station’s catastrophic decline. As they explore, players will crawl through air vents, scope out hiding places, scavenge for resources, and deploy tech in a life-or-death struggle to outthink the terrifying Alien, whose unpredictable, dynamic behaviour evolves after each encounter. Alien: Isolation on Nintendo Switch will feature technologies such as gyroscopic aiming and HD rumble to immerse players in its terrifying world wherever they play. A trailer for Alien: Isolation on Switch is available now. About Feral Interactive Feral Interactive is a leading publisher of games for the macOS, Linux, iOS and Android platforms, founded in 1996 and based in London, England. -

Redeye-Gaming-Guide-2020.Pdf

REDEYE GAMING GUIDE 2020 GAMING GUIDE 2020 Senior REDEYE Redeye is the next generation equity research and investment banking company, specialized in life science and technology. We are the leading providers of corporate broking and corporate finance in these sectors. Our clients are innovative growth companies in the nordics and we use a unique rating model built on a value based investment philosophy. Redeye was founded 1999 in Stockholm and is regulated by the swedish financial authority (finansinspektionen). THE GAMING TEAM Johan Ekström Tomas Otterbeck Kristoffer Lindström Jonas Amnesten Head of Digital Senior Analyst Senior Analyst Analyst Entertainment Johan has a MSc in finance Tomas Otterbeck gained a Kristoffer Lindström has both Jonas Amnesten is an equity from Stockholm School of Master’s degree in Business a BSc and an MSc in Finance. analyst within Redeye’s tech- Economic and has studied and Economics at Stockholm He has previously worked as a nology team, with focus on e-commerce and marketing University. He also studied financial advisor, stockbroker the online gambling industry. at MBA Haas School of Busi- Computing and Systems and equity analyst at Swed- He holds a Master’s degree ness, University of California, Science at the KTH Royal bank. Kristoffer started to in Finance from Stockholm Berkeley. Johan has worked Institute of Technology. work for Redeye in early 2014, University, School of Business. as analyst and portfolio Tomas was previously respon- and today works as an equity He has more than 6 years’ manager at Swedbank Robur, sible for Redeye’s website for analyst covering companies experience from the online equity PM at Alfa Bank and six years, during which time in the tech sector with a focus gambling industry, working Gazprombank in Moscow he developed its blog and on the Gaming and Gambling in both Sweden and Malta as and as hedge fund PM at community and was editor industry. -

Specializations Faq

DRAGON AGE: ORIGINS SPECIALIZATIONS FAQ WARRIORS BERSERKER CHAMPION REAVER TEMPLAR The first berserkers were The champion is a veteran Demonic spirits teaches Mages who refuses Circle’s dwarves. They would warrior and a confident more than blood magic. control becomes apostate sacrifice finesse for a dark leader in battle. Possessing Reavers terrorize their and live in a fear of rage that increased their skills at arms impressive enemies, feast upon the templar’s powers – the strength and resilience. enough to inspire allies, the souls of their slain ability to dispel and resist Eventually, dwarves taught champion can also opponents to heal their own magic. As servants of the these skills to others, and intimidate and demoralize flesh, and can unleash a chantry, the templars have now berserkers can be foes. These are heroes you bloody frenzy that makes been the most effective found amongst all races. find commanding an army, them more powerful as they means of controlling the They are renowned as or plunging headlong into come to nearer to their own spread and use of arcane terrifying adversaries. danger, somehow making it death. power for centuries. look easy. +2 strength. +10 health +1 constitution, +5 physical +2 magic, +3 magic +2 willpower, +1 cunning resistance resistance SOURCE: By Oghren or a manual available from Gorim SOURCE: By Arl Eamon SOURCE: By Korgrim after SOURCE: By Alistair or a in Denerim market district. after healing him using the poisoning the Urn of the manual available from Urn of the Sacred Ashes. Sacred Ashes. Bodahn and Sandal in the Party Camp. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year Ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries Years ended March 31, 1998, 1999 and 2000 Thousands of Millions of yen U.S. dollars 1998 1999 2000 2000 For the year: Net sales: Consumer products ........................................................................................................ ¥114,457 ¥084,694 ¥186,189 $1,754,018 Amusement center operations ...................................................................................... 94,521 93,128 79,212 746,227 Amusement machine sales............................................................................................ 122,627 88,372 73,654 693,867 Total ........................................................................................................................... ¥331,605 ¥266,194 ¥339,055 $3,194,112 Cost of sales ...................................................................................................................... ¥270,710 ¥201,819 ¥290,492 $2,736,618 Gross profit ........................................................................................................................ 60,895 64,375 48,563 457,494 Selling, general and administrative expenses .................................................................. 74,862 62,287 88,917 837,654 Operating (loss) income ..................................................................................................... (13,967) 2,088 (40,354) (380,160) Net loss............................................................................................................................. -

Roll 2D6 to Kill

1 Roll 2d6 to kill Neoliberal design and its affect in traditional and digital role-playing games Ruben Ferdinand Brunings August 15th, 2017 Table of contents 2 Introduction: Why we play 3. Part 1 – The history and neoliberalism of play & table-top role-playing games 4. Rules and fiction: play, interplay, and interstice 5. Heroes at play: Quantification, power fantasies, and individualism 7. From wargame to warrior: The transformation of violence as play 9. Risky play: chance, the entrepreneurial self, and empowerment 13. It’s ‘just’ a game: interactive fiction and the plausible deniability of play 16. Changing the rules, changing the game, changing the player 18. Part 2 – Technics of the digital game: hubristic design and industry reaction 21. Traditional vs. digital: a collaborative imagination and a tangible real 21. Camera, action: The digitalisation of the self and the representation of bodies 23. The silent protagonist: Narrative hubris and affective severing in Drakengard 25. Drakengard 3: The spectacle of violence and player helplessness 29. Conclusion: Games, conventionality, and the affective power of un-reward 32. References 36. Bibliography 38. Introduction: Why we play 3 The approach of violence or taboo in game design is a discussion that has historically been a controversial one. The Columbine shooting caused a moral panic for violent shooter video games1, the 2007 game Mass Effect made FOX News headlines for featuring scenes of partial nudity2, and the FBI kept tabs on Dungeons & Dragons hobbyists for being potential threats after the Unabomber attacks.3 The question ‘Do video games make people violent?’ does not occur within this thesis. -

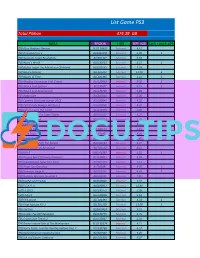

List Game PS3

List Game PS3 Total Pilihan 474.39 GB JUDUL REGION HDD SIZE (GB) ketik 1 untuk pilih [TB] Alice Madness Returns BLUS 30607 External 4.51 [TB] Armored Core V BLJM60378 External 4.00 1 [TB] Assassins Creed Revelations BLES01467 External 8.53 [TB] Asura's Wrath BLUS30721 External 6.52 1 [TB] Atelier Totori The Adventurer Of Arland BLUS30735 External 4.38 [TB] Binary Domain BLES01211 External 11.20 1 [TB] Blades of Time BLES01395 External 2.21 1 [TB] BlazBlue Continuum Shift Extend BLUS30869 Internal 9.30 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Ignition BCJS30077 External 3.15 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Resurreccion BLUS30769 External 3.88 [TB] Bodycount BLES01314 External 5.06 [TB] Cabela's Big Game Hunter 2012 BLUS30843 External 4.10 [TB] Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3 BLUS30838 External 8.02 [TB] Call of Juarez The Cartel BLUS30795 External 5.06 [TB] Captain America Super Soldier BLES01167 External 6.23 [TB] Carnival Island BCUS98271 External 2.73 [TB] Catherine US BLUS30428 External 9.56 [TB] Child of Eden BLES01114 External 2.16 [TB] Dark Souls BLES01402 External 4.62 [TB] Dead Island BLES00749 External 3.46 [TB] Dead Rising 2 Off The Record BLUS30763 External 5.37 [TB] Deus Ex Human Revolution BLES01150 External 8.11 [TB] Dirt 3 BLES 01287 Internal 6.32 1 [TB] Dragon Ball Z Ultimate Tenkaichi BLUS30823 External 6.98 [TB] DreamWorks Super Star Kartz BLES01373 External 2.15 [TB] Driver San Fransisco BLES00891 External 9.05 1 [TB] Dungeon Siege III BLES01161 External 4.50 1 [TB] Dynasty Warriors Gundam 3 BLES01301 External 7.82 [TB] EyePet and Friends BCES00865 Internal 7.47 [TB] F.E.A.R. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Comparative Life Cycle Impact Assessment of Digital and Physical Distribution of Video Games in the United States

Comparative Life Cycle Impact Assessment of Digital and Physical Distribution of Video Games in the United States The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Buonocore, Cathryn E. 2016. Comparative Life Cycle Impact Assessment of Digital and Physical Distribution of Video Games in the United States. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797406 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Comparative Life Cycle Impact Assessment of Digital and Physical Distribution of Video Games in the United States Cathryn E. Buonocore A Thesis in the field of Sustainability for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 Copyright 2016 Cathryn E. Buonocor Abstract This study examines and compares the environmental footprint of video game distribution on last generation consoles, current generation consoles and personal computers (PC). Two different methods of delivery are compared on each platform: traditional retail on optical discs and digital downloads in the U.S. Downloading content has been growing and is used to distribute movies, music, books and video games. This technology may change the environmental footprint of entertainment media. Previous studies on books, music, movies and television shows found that digital methods of distribution reduced emissions. However, prior research on video games, looking only at previous generation consoles, found the opposite conclusion. -

The Story of Cluedo & Clue a “Contemporary” Game for Over 60 Years

The story of Cluedo & Clue A “Contemporary” Game for over 60 Years by Bruce Whitehill The Metro, a free London newspaper, regularly carried a puzzle column called “Enigma.” In 2005, they ran this “What-game-am-I?” riddle: Here’s a game that’s lots of fun, Involving rope, a pipe, a gun, A spanner, knife and candlestick. Accuse a friend and make it stick. The answer was the name of a game that, considering the puzzle’s inclusion in a well- known newspaper, was still very much a part of British popular culture after more than 50 years: “Cluedo,” first published in 1949 in the UK. The game was also published under license to Parker Brothers in the United States the same year, 1949. There it is was known as: Clue What’s in a name? • Cluedo = Clue + Ludo" Ludo is a classic British game -- " a simplified Game of India • Ludo is not played in the U.S. " Instead, Americans play Parcheesi." But “Cluecheesi” doesn’t quite work." So we just stuck with “Clue” I grew up (in New York) playing Clue, and like most other Americans, considered it to be one of America’s classic games. Only decades later did I learn its origin was across the ocean, in Great Britain. Let me take you back to England, 1944. With the Blitz -- the bombing -- and the country emersed in a world war, the people were subject to many hardships, including blackouts and rationing. A forty-one-year-old factory worker in Birmingham was disheartened because the blackouts and the crimp on social activities in England meant he was unable to play his favorite parlor game, called “Murder.” “Murder” was a live-action party game where guests tried to uncover the person in the room who had been secretly assigned the role of murderer. -

Video Games As Culture

There are only a few works that aim for a comprehensive mapping of what games as a culture are, and how their complex social and cultural realities should be stud- ied, as a whole. Daniel Muriel and Garry Crawford have done so, analyzing both games, players, associated practices, and the broad range of socio-cultural develop- ments that contribute to the ongoing ludification of society. Ambitious, lucid, and well-informed, this book is an excellent guide to the field, and will no doubt inspire future work. Frans Mäyrä, Professor of Information Studies and Interactive Media, University of Tampere This book provides an insightful and accessible contribution to our understand- ing of video games as culture. However, its most impressive achievement is that it cogently shows how the study of video games can be used to explore broader social and cultural processes, including identity, agency, community, and consumption in contemporary digital societies. Muriel and Crawford have written a book that transcends its topic, and deserves to be read widely. Aphra Kerr, Senior Lecturer in Sociology, Maynooth University This page intentionally left blank VIDEO GAMES AS CULTURE Video games are becoming culturally dominant. But what does their popularity say about our contemporary society? This book explores video game culture, but in doing so, utilizes video games as a lens through which to understand contemporary social life. Video games are becoming an increasingly central part of our cultural lives, impacting on various aspects of everyday life such -

WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

1 MONSTROSITIES MADE IN THE INTERFACE: THE IDEOLOGICAL RAMIFICATIONS OF ‘PLAYING’ WITH OUR DEMONS A Thesis submitted by Jesse J Warren, BLM Student ID: u1060927 For the award of Master of Arts (Humanities and Communication) 2020 Thesis Certification Page This thesis is entirely the work of Jesse Warren except where otherwise acknowledged. This work is original and has not previously been submitted for any other award, except where acknowledged. Signed by the candidate: __________________________________________________________________ Principal Supervisor: _________________________________________________________________ Abstract Using procedural rhetoric to critique the role of the monster in survival horror video games, this dissertation will discuss the potential for such monsters to embody ideological antagonism in the ‘game’ world which is symptomatic of the desire to simulate the ideological antagonism existing in the ‘real’ world. Survival video games explore ideology by offering a space in which to fantasise about society's fears and desires in which the sum of all fears and object of greatest desire (the monster) is so terrifying as it embodies everything 'other' than acceptable, enculturated social and political behaviour. Video games rely on ideology to create believable game worlds as well as simulate believable behaviours, and in the case of survival horror video games, to simulate fear. This dissertation will critique how the games Alien:Isolation, Until Dawn, and The Walking Dead Season 1 construct and themselves critique representations of the ‘real’ world, specifically the way these games position the player to see the monster as an embodiment of everything wrong and evil in life - everything 'other' than an ideal, peaceful existence, and challenge the player to recognise that the very actions required to combat or survive this force potentially serve as both extensions of existing cultural ideology and harbingers of ideological resistance across two worlds – the ‘real’ and the ‘game’.