Community Abstract Dry Sand Prairie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Plants of East Central Illinois and Their Preferred Locations”

OCTOBER 2007 Native Plants at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Campus: A Sourcebook for Landscape Architects and Contractors James Wescoat and Florrie Wescoat with Yung-Ching Lin Champaign, IL October 2007 Based on “Native Plants of East Central Illinois and their Preferred Locations” An Inventory Prepared by Dr. John Taft, Illinois Natural History Survey, for the UIUC Sustainable Campus Landscape Subcommittee - 1- 1. Native Plants and Plantings on the UIUC Campus This sourcebook was compiled for landscape architects working on projects at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign campus and the greater headwaters area of east central Illinois.1 It is written as a document that can be distributed to persons who may be unfamiliar with the local flora and vegetation, but its detailed species lists and hotlinks should be useful for seasoned Illinois campus designers as well. Landscape architects increasingly seek to incorporate native plants and plantings in campus designs, along with plantings that include adapted and acclimatized species from other regions. The term “native plants” raises a host of fascinating scientific, aesthetic, and practical questions. What plants are native to East Central Illinois? What habitats do they occupy? What communities do they form? What are their ecological relationships, aesthetic characteristics, and practical limitations? As university campuses begin to incorporate increasing numbers of native species and areas of native planting, these questions will become increasingly important. We offer preliminary answers to these questions, and a suite of electronic linkages to databases that provide a wealth of information for addressing more detailed issues. We begin with a brief introduction to the importance of native plants in the campus environment, and the challenges of using them effectively, followed by a description of the database, online resources, and references included below. -

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

Plant Propagation Protocol for Carex inops ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production TAXONOMY Family Names Family Scientific Name: Cyperaceae Family Common Name: Sedge Scientific Names Genus: Carex Species: inops Species Authority: L. H. Bailey Variety: Sub-species: Cultivar: Authority for Variety/Sub-species: Common Synonym(s) (include full CAINI3 Carex inops L.H. Bailey ssp inops scientific names (e.g., Elymus CAINH2 Carex inops ssp heliophila (Mack.) Crins glaucus Buckley), including variety Synonyms for ssp heliophila or subspecies information) CAER5 Carex erxlebeniana L. Kelso CAHE5 Carex heliophila Mack. CAPEH Carex pensylvanica Lam. ssp. Heliophila (Mack.) W.A. Weber CAPED Carex pensylvanica Lam. var. digyna Boeckeler Common Name(s): long-stolon sedge or sun sedge (ssp heliophila) Species Code (as per USDA Plants CAIN9 database): GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range (distribution maps for North America and Washington state) http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=CAIN9 http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=CAIN9 Ecological distribution (ecosystems it Found in shortgrass, mixed, and tallgrass prairies, as occurs in, etc): well as Ponderosa pine communities and other woodlands (Fryer 2009) Climate and elevation range Dry to seasonally wet climates. Occasionally found at elevations > 5000 ft.(Fryer 2009) Local habitat and abundance; may May dominate to co-dominate in some systems. High include commonly associated prevelance and persistance even in systems where it is species not the dominant species. (Fryer 2009) Plant strategy -

Ecological Site Description Section L: Ecological Site Characteristics Ecological Site Identification and Concept

ESD Printable Report Page 1 of 56 United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Ecological Site Description Section l: Ecological Site Characteristics Ecological Site Identification and Concept Site stage: Provisional Provisional: an ESD at the provisional status represents the lowest tier of documentation that is releasable to the public. It contains a grouping of soil units that respond similarly to ecological processes. The ESD contains 1) enough information to distinguish it from similar and associated ecological sites and 2) a draft state and transition model capturing the ecological processes and vegetative states and community phases as they are currently conceptualized. The provisional ESD has undergone both quality control and quality assurance protocols. It is expected that the provisional ESD will continue refinement towards an approved status. Site name: Clayey / Pascopyrum smithii - Nassella viridula ( / western wheatgrass - green needlegrass) Site type: Rangeland Site ID: R058DY011SD Major land resource area (MLRA): 058D-Northern Rolling High Plains, Eastern Part https://esis.sc.egov.usda.gov/ESDReport/fsReportPrt.aspx?id=R058DY011SD&rptLevel=... 5/27/2016 ESD Printable Report Page 2 of 56 Physiographic Features This site occurs on nearly level to moderately steep uplands. Landform: (1) Terrace (2) Hill (3) Plain Minimum Maximum Elevation (feet): 2300 4000 Slope (percent): 0 6 Water table depth (inches): 80 80 Flooding Frequency: None None Ponding Frequency: None None Runoff class: High Very high Aspect: No Influence on this site Climatic Features https://esis.sc.egov.usda.gov/ESDReport/fsReportPrt.aspx?id=R058DY011SD&rptLevel=... 5/27/2016 ESD Printable Report Page 3 of 56 The climate in this MLRA is typical of the drier portions of the Northern Great Plains where sagebrush steppes to the west yield to grassland to the east. -

Key Points for Sustainable Management of Northern Great Plains Grasslands

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Natural Resource Management Faculty Publications Department of Natural Resource Management 2019 Looking to the Future: Key Points for Sustainable Management of Northern Great Plains Grasslands Lora B. Perkins Marissa Ahlering Diane L. Larson Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/nrm_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons REVIEW ARTICLE Looking to the future: key points for sustainable management of northern Great Plains grasslands Lora B. Perkins1,2 , Marissa Ahlering3, Diane L. Larson4 The grasslands of the northern Great Plains (NGP) region of North America are considered endangered ecosystems and priority conservation areas yet have great ecological and economic importance. Grasslands in the NGP are no longer self-regulating adaptive systems. The challenges to these grasslands are widespread and serious (e.g. climate change, invasive species, fragmentation, altered disturbance regimes, and anthropogenic chemical loads). Because the challenges facing the region are dynamic, complex, and persistent, a paradigm shift in how we approach restoration and management of the grasslands in the NGP is imperative. The goal of this article is to highlight four key points for land managers and restoration practitioners to consider when planning management or restoration actions. First, we discuss the appropriateness of using historical fidelity as a restoration or management target because of changing climate, widespread pervasiveness of invasive species, the high level of fragmentation, and altered disturbance regimes. -

Common Wildflowers Found at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve

Useful books and websites Great Plains Flora Association. T.M. Barkley, editor. National Park Service Flora of the Great Plains. University Press of Kansas, 1986. U.S. Department of the Interior Haddock, Michael John. Wildflowers and Grasses of Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Kansas: A Field Guide. University Press of Kansas, 2005. Strong City, Kansas Ladd, Doug. Tallgrass Prairie Wildflowers. Falcon Press Publishing, 1995. Common Wildflowers Found at Wooly verbena Snow-on-the-mountain Cardinal flower Maximilian sunflower Owensby, Clenton E. Kansas Prairie Wildflowers. KS Euphorbia marginata Lobelia cardinalis Helianthus maximilianii Verbena stricta Publishing, Inc. 2004. Blooms: June - September Blooms: June - October Blooms: August - September Blooms: August - September Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Kansas Native Plants Society: www.kansasnativeplantsociety.org Kansas Wildflowers and Grasses: www.kswildflower.org Image Credits The images used in this brochure (unless otherwise noted) are credited to Mike Haddock, Agriculture Librarian Common sunflower Compass plant Round-head bush clover Broomweed and Chair of the Sciences Department at Kansas State Wild parsley Cream wild indigo Helianthus annuus Silphium laciniatum Lespedeza capitata Gutierrezia dracunculoides University Libraries and editor of the website Kansas Lomatium foeniculaceum Baptisia bracteata Blooms: July - September Blooms: August - September Blooms: August - October Blooms: March - April Blooms: April - May Blooms: July - September Wildflowers and Grasses at -

Species List (PDF)

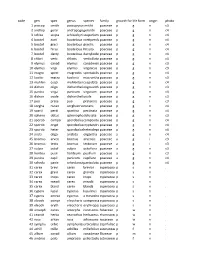

code gen spec genus species family growth formlife form origin photo 1 pascop smith pascopyrumsmithii poaceae p g n c3 2 androp gerar andropogongerardii poaceae p g n c4 3 schiza scopa schizachyriumscoparium poaceae p g n c4 4 boutel curti bouteloua curtipendulapoaceae p g n c4 5 boutel graci bouteloua gracilis poaceae p g n c4 6 boutel hirsu bouteloua hirsuta poaceae p g n c4 7 boutel dacty bouteloua dactyloidespoaceae p g n c4 8 chlori verti chloris verticillata poaceae p g n c4 9 elymus canad elymus canadensispoaceae p g n c3 10 elymus virgi elymus virginicus poaceae p g n c3 11 eragro spect eragrostis spectabilis poaceae p g n c4 12 koeler macra koeleria macrantha poaceae p g n c3 13 muhlen cuspi muhlenbergiacuspidata poaceae p g n c4 14 dichan oligo dichantheliumoligosanthespoaceae p g n c3 15 panicu virga panicum virgatum poaceae p g n c4 16 dichan ovale dichantheliumovale poaceae p g n c3 17 poa prate poa pratensis poaceae p g i c3 18 sorgha nutan sorghastrumnutans poaceae p g n c4 19 sparti pecti spartina pectinata poaceae p g n c4 20 spheno obtus sphenopholisobtusata poaceae p g n c3 21 sporob compo sporoboluscomposituspoaceae p g n c4 22 sporob crypt sporoboluscryptandruspoaceae p g n c4 23 sporob heter sporobolusheterolepispoaceae p g n c4 24 aristi oliga aristida oligantha poaceae a g n c4 25 bromus arven bromus arvensis poaceae a g i c3 26 bromus tecto bromus tectorum poaceae a g i c3 27 vulpia octof vulpia octoflora poaceae a g n c3 28 hordeu pusil hordeum pusillum poaceae a g n c3 29 panicu capil panicum capillare poaceae a g n c4 30 schedo panic schedonnarduspaniculatuspoaceae p g n c4 31 carex brevi carex brevior cyperaceaep s n . -

Dry Grassland Vegetation of Central Podolia (Ukraine) - a Preliminary Overview of Its Syntaxonomy, Ecology and Biodiversity 391-430 Tuexenia 34: 391–430

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Tuexenia - Mitteilungen der Floristisch-soziologischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Jahr/Year: 2014 Band/Volume: NS_34 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kuzenko Anna A., Becker Thomas, Didukh Yakiv P., Ardelean Ioana Violeta, Becker Ute, Beldean Monika, Dolnik Christian, Jeschke Michael, Naqinezhad Alireza, Ugurlu Emin, Unal Aslan, Vassilev Kiril, Vorona Evgeniy I., Yavorska Olena H., Dengler Jürgen Artikel/Article: Dry grassland vegetation of Central Podolia (Ukraine) - a preliminary overview of its syntaxonomy, ecology and biodiversity 391-430 Tuexenia 34: 391–430. Göttingen 2014. doi: 10.14471/2014.34.020, available online at www.tuexenia.de Dry grassland vegetation of Central Podolia (Ukraine) – a preliminary overview of its syntaxonomy, ecology and biodiversity Die Trockenrasenvegetation Zentral-Podoliens (Ukraine) – eine vorläufige Übersicht zu Syntaxonomie, Ökologie und Biodiversität Anna A. Kuzemko1, Thomas Becker2, Yakiv P. Didukh3, Ioana Violeta Arde- lean4, Ute Becker5, Monica Beldean4, Christian Dolnik6, Michael Jeschke2, Alireza Naqinezhad7, Emin Uğurlu8, Aslan Ünal9, Kiril Vassilev10, Evgeniy I. Vorona11, Olena H. Yavorska11 & Jürgen Dengler12,13,14,* 1National Dendrological Park “Sofiyvka”, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyivska Str. 12a, 20300 Uman’, Ukraine, [email protected];2Geobotany, Faculty of Geography and Geosciences, University of Trier, Behringstr. 21, 54296 Trier, Germany, [email protected]; -

Rosemount Greenway Restoration Plan Site Assessment Site N3

Rosemount Greenway Restoration Plan Site Assessment Site N3 14th December, 2014 Submitted by : Group N3 (Cody Madaus, Megan Butler, Niluja Singh) This project was supported by the Resilient Communities Project (RCP), a program at the University of Minnesota that convenes the wide-ranging expertise of U of M faculty and students to address strategic local projects that advance community resilience and sustainability. RCP is a program of the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) and the Institute on the Environment. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Any reproduction, distribution, or derivative use of this work under this license must be accompanied by the following attribution: “Produced by the Resilient Communities Project at the University of Minnesota, 2014. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.” This publication may be available in alternate formats upon request. Resilient Communities Project University of Minnesota 330 HHHSPA 301—19th Avenue South Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 Phone: (612) 625-7501 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.rcp.umn.edu The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, disability, public assistance status, veteran status, or sexual orientation. Table of Contents Part 1: Site Assessment………………………………………………………………………..1 Part 1.1 Greenway (Landscape) Assessment……………………………1 1. -

Native Or Suitable Plants City of Mccall

Native or Suitable Plants City of McCall The following list of plants is presented to assist the developer, business owner, or homeowner in selecting plants for landscaping. The list is by no means complete, but is a recommended selection of plants which are either native or have been successfully introduced to our area. Successful landscaping, however, requires much more than just the selection of plants. Unless you have some experience, it is suggested than you employ the services of a trained or otherwise experienced landscaper, arborist, or forester. For best results it is recommended that careful consideration be made in purchasing the plants from the local nurseries (i.e. Cascade, McCall, and New Meadows). Plants brought in from the Treasure Valley may not survive our local weather conditions, microsites, and higher elevations. Timing can also be a serious consideration as the plants may have already broken dormancy and can be damaged by our late frosts. Appendix B SELECTED IDAHO NATIVE PLANTS SUITABLE FOR VALLEY COUNTY GROWING CONDITIONS Trees & Shrubs Acer circinatum (Vine Maple). Shrub or small tree 15-20' tall, Pacific Northwest native. Bright scarlet-orange fall foliage. Excellent ornamental. Alnus incana (Mountain Alder). A large shrub, useful for mid to high elevation riparian plantings. Good plant for stream bank shelter and stabilization. Nitrogen fixing root system. Alnus sinuata (Sitka Alder). A shrub, 6-1 5' tall. Grows well on moist slopes or stream banks. Excellent shrub for erosion control and riparian restoration. Nitrogen fixing root system. Amelanchier alnifolia (Serviceberry). One of the earlier shrubs to blossom out in the spring. -

Wildflower Plant Characteristics for Pollinator and Conservation Plantings

Wildflower Plant Characteristics for Pollinator and Conservation Plantings Prepared By: Shawnna Clark and Kelly Gill 1 Wildflower Plant Characteristics for Pollinator and Conservation Plantings in the Northeast US Soil Bloom Bloom Height Wetland Scientific Name Common name Drainage Seeds/# 5 Other Time2 Color (ft)3 Indicator4 Class Achillea millefolium yarrow july-aug white 1-3 WD-MWD FACU 180,000 low moisture needs july- Establishes quickly, fragrant showy spikes of flowers on upper Agastache foeniculum anise hyssop purple 2-5 WD-MWD UPL 1,400,000 sept stems, grows best in full-partial sun and dry-medium moisture Agastache purple giant july- purple 3-4 MWD-SPD FACW 1,240,000 attractive to bees and butterflies, birds scrophulariifolia hyssop sept june- Apocynum cannabinum Indian hemp white 2-4 WD-SPD FACU 500,000 extensive root system, aggressive and can become weedy aug One of the earliest wildflowers to bloom; striking red flowers with Aquilegia canadensis Eastern columbine apr red 1-2 WD FACU 504,000 yellow centers; grows best in partial shade and moist soils pink/ Asclepias exalta poke milkweed july-aug 4-6 WD-MWD UPL 48,000 great for wood edges purple branching habit; grows best in full-partial sun and moderate-wet Asclepias incarnata swamp milkweed july-aug pink 3-6 SPD-PD OBL 75,000 conditions; tolerates occasional flooding; great for monarch; high deer resistant, slow to spread common pink grows best in full sun and moist soils; but will tolerate a variety of Asclepias syriaca july-aug 3-4 WD-MWD UPL 70,000 milkweed purple situations; -

Palynological Evolutionary Trends Within the Tribe Mentheae with Special Emphasis on Subtribe Menthinae (Nepetoideae: Lamiaceae)

Plant Syst Evol (2008) 275:93–108 DOI 10.1007/s00606-008-0042-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Palynological evolutionary trends within the tribe Mentheae with special emphasis on subtribe Menthinae (Nepetoideae: Lamiaceae) Hye-Kyoung Moon Æ Stefan Vinckier Æ Erik Smets Æ Suzy Huysmans Received: 13 December 2007 / Accepted: 28 March 2008 / Published online: 10 September 2008 Ó Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract The pollen morphology of subtribe Menthinae Keywords Bireticulum Á Mentheae Á Menthinae Á sensu Harley et al. [In: The families and genera of vascular Nepetoideae Á Palynology Á Phylogeny Á plants VII. Flowering plantsÁdicotyledons: Lamiales (except Exine ornamentation Acanthaceae including Avicenniaceae). Springer, Berlin, pp 167–275, 2004] and two genera of uncertain subtribal affinities (Heterolamium and Melissa) are documented in Introduction order to complete our palynological overview of the tribe Mentheae. Menthinae pollen is small to medium in size The pollen morphology of Lamiaceae has proven to be (13–43 lm), oblate to prolate in shape and mostly hexacol- systematically valuable since Erdtman (1945) used the pate (sometimes pentacolpate). Perforate, microreticulate or number of nuclei and the aperture number to divide the bireticulate exine ornamentation types were observed. The family into two subfamilies (i.e. Lamioideae: bi-nucleate exine ornamentation of Menthinae is systematically highly and tricolpate pollen, Nepetoideae: tri-nucleate and hexa- informative particularly at generic level. The exine stratifi- colpate pollen). While the -

Dotted Gayfeather Is a Good Addition to a Sunny Flower Garden Or a Prairie Planting for Its Long Lasting Purple Color in Late Summer and Early Fall

Plant Fact Sheet depending on the time of year collected. Although DOTTED widely distributed over the prairies, gayfeather is not mentioned widely as a food source of native people. GAYFEATHER The Lakota pulverized the roots of gayfeather and ate them to improve appetite. For heart pains they Liatris punctata Hook. powdered the entire plant and made a tea. The Plant Symbol = LIPU Blackfeet boiled the gayfeather root and applied it to swellings. They made a tea for stomach aches, but Contributed by: USDA NRCS Plant Materials Center sometimes just ate the root raw instead. The Pawnee Manhattan, Kansas boiled the root and leaves together and fed the tea to children with diarrhea. The Omaha powdered the root and applied it as a poultice for external inflammation. They also made a tea from the plant to treat abdominal troubles. The roots were also used as a folk medicine for sore throats and as a treatment for rattle snake bite. Horticultural: Gayfeather plants are becoming more popular for ornamental uses, especially fresh floral arrangements and winter bouquets. The inflorescences make good long lasting cut flowers. If spikes are picked at their prime and allowed to dry out of the sun, they will retain their color and can be used in dried plant arrangements. Dotted gayfeather is a good addition to a sunny flower garden or a prairie planting for its long lasting purple color in late summer and early fall. This species also offers promise for roadside and rest stop beautification projects in the Great Plains region. Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g.