Rosemount Greenway Restoration Plan Site Assessment Site N3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Wildflowers Found at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve

Useful books and websites Great Plains Flora Association. T.M. Barkley, editor. National Park Service Flora of the Great Plains. University Press of Kansas, 1986. U.S. Department of the Interior Haddock, Michael John. Wildflowers and Grasses of Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Kansas: A Field Guide. University Press of Kansas, 2005. Strong City, Kansas Ladd, Doug. Tallgrass Prairie Wildflowers. Falcon Press Publishing, 1995. Common Wildflowers Found at Wooly verbena Snow-on-the-mountain Cardinal flower Maximilian sunflower Owensby, Clenton E. Kansas Prairie Wildflowers. KS Euphorbia marginata Lobelia cardinalis Helianthus maximilianii Verbena stricta Publishing, Inc. 2004. Blooms: June - September Blooms: June - October Blooms: August - September Blooms: August - September Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Kansas Native Plants Society: www.kansasnativeplantsociety.org Kansas Wildflowers and Grasses: www.kswildflower.org Image Credits The images used in this brochure (unless otherwise noted) are credited to Mike Haddock, Agriculture Librarian Common sunflower Compass plant Round-head bush clover Broomweed and Chair of the Sciences Department at Kansas State Wild parsley Cream wild indigo Helianthus annuus Silphium laciniatum Lespedeza capitata Gutierrezia dracunculoides University Libraries and editor of the website Kansas Lomatium foeniculaceum Baptisia bracteata Blooms: July - September Blooms: August - September Blooms: August - October Blooms: March - April Blooms: April - May Blooms: July - September Wildflowers and Grasses at -

Dotted Gayfeather Is a Good Addition to a Sunny Flower Garden Or a Prairie Planting for Its Long Lasting Purple Color in Late Summer and Early Fall

Plant Fact Sheet depending on the time of year collected. Although DOTTED widely distributed over the prairies, gayfeather is not mentioned widely as a food source of native people. GAYFEATHER The Lakota pulverized the roots of gayfeather and ate them to improve appetite. For heart pains they Liatris punctata Hook. powdered the entire plant and made a tea. The Plant Symbol = LIPU Blackfeet boiled the gayfeather root and applied it to swellings. They made a tea for stomach aches, but Contributed by: USDA NRCS Plant Materials Center sometimes just ate the root raw instead. The Pawnee Manhattan, Kansas boiled the root and leaves together and fed the tea to children with diarrhea. The Omaha powdered the root and applied it as a poultice for external inflammation. They also made a tea from the plant to treat abdominal troubles. The roots were also used as a folk medicine for sore throats and as a treatment for rattle snake bite. Horticultural: Gayfeather plants are becoming more popular for ornamental uses, especially fresh floral arrangements and winter bouquets. The inflorescences make good long lasting cut flowers. If spikes are picked at their prime and allowed to dry out of the sun, they will retain their color and can be used in dried plant arrangements. Dotted gayfeather is a good addition to a sunny flower garden or a prairie planting for its long lasting purple color in late summer and early fall. This species also offers promise for roadside and rest stop beautification projects in the Great Plains region. Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. -

Providing for Pollinators: Conserving and Integrating Natural Habitats to Support Pollinator Conservation Efforts

Providing for pollinators: conserving and integrating natural habitats to support pollinator conservation efforts by Jessica Nicole Butters B.A., Central College, 2017 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Entomology College of Agriculture KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2021 Approved by: Major Professor Tania Kim Copyright © Jessica Nicole Butters 2021. Abstract Pollinators have been in decline for at least the past four decades due to habitat loss from agricultural intensification. Natural pollinator habitat, such as tallgrass prairies, have shrunk to less than 10% of their original extent. Because over one-third of food crops are completely pollinator-dependent, we are under the threat of food instability if pollinator decline is not stabilized and improved. Additionally, little work has been done in terms of understanding how different land management strategies, such as fire rotations or native flower plantings, impact different groups of pollinators, such as bees and butterflies. In an effort to address these issues, I implemented a two-year study on the impact of conservation and ecological intensification strategies on pollinators. My objectives were to 1) understand how fire and grazing management on a prairie reserve impacts the pollinator community and 2) examine how land managers can attract and provide for pollinators in an agricultural setting through the implementation of perennial border crops. For my first objective, I found that bison grazing had positive effects on nearly all pollinators, from lepidopterans to ground-nesting bees, while different fire rotations had both positive and negative effects on pollinators through different pathways. -

Conservation Assessment for Iowa Moonwort (Botrychium Campestre)

Conservation Assessment for Iowa Moonwort (Botrychium campestre) Botrychium campestre. Drawing provided by USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2001 Prepared by: Steve Chadde & Greg Kudray for USDA Forest Service, Region 9 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Iowa Moonwort (Botrychium campestre) 2 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION/OBJECTIVES.............................................................. 4 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY .................................................. 5 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES .................................................................... 5 LIFE HISTORY........................................................................................... -

Chapter 1 Overview of Planning

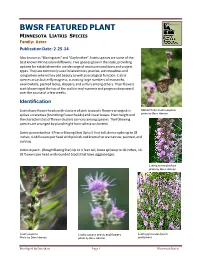

PO BWSR FEATURED PLANT MINNESOTA LIATRIS SPECIES Family: Aster Publication Date: 2-25-14 Also known as “Blazingstars” and “Gayfeather”, liatris species are some of the best known Minnesota wildflowers. Five species grow in the state, providing options for establishment in a wide range of moisture conditions and project types. They are commonly used in lakeshores, prairies, wet meadows and raingardens where they add beauty as well as ecological function. Liatris species act as butterfly magnets, attracting large numbers of monarchs, swallowtails, painted ladies, skippers, and sulfurs among others. Their flowers start blooming at the top of the stalk in mid-summer and progress downward over the course of a few weeks. Identification Liatris have flower heads with clusters of pink to purple flowers arranged in Monarch on Liatris aspera photo by Dave Hanson spikes or racemes (branching flower heads) and linear leaves. Plant height and the characteristics of flower clusters can vary among species. The following species are arranged by plant height from tallest to shortest. Liatris pycnostachya - (Prairie Blazing Star) Up to 5 feet tall, dense spike up to 18 inches, 4-18 flowers per head with pinkish-red bracts that are narrow, pointed, and curving. Liatris aspera - (Rough Blazing Star) Up to 4 feet tall, loose spike up to 18 inches, 16- 35 flowers per head with rounded bracts that have jagged edges. Liatris pycnostachya photo by Dave Hanson Liatris aspera Liatris aspera bracts and flowers Liatris pycnostachya in Photo by Dave Hanson photo by Dave Hanson containers Developed by Dan Shaw Page 1 Minnesota Liatris Liatris ligulistylis - (Northern Plains Blazing Star) Up to 3.5 feet tall, loose raceme up to 18 inches, 30-80 flowers per head with green to purplish bracts that have rounded tips. -

Foods Eaten by the Rocky Mountain

were reported as trace amounts were excluded. Factors such as relative plant abundance in relation to consumption were considered in assigning plants to use categories when such information was Foods Eaten by the available. An average ranking for each species was then determined on the basis Rocky Mountain Elk of all studies where it was found to contribute at least 1% of the diet. The following terminology is used throughout this report. Highly valuable plant-one avidly sought by elk and ROLAND C. KUFELD which made up a major part of the diet in food habits studies where encountered, or Highlight: Forty-eight food habits studies were combined to determine what plants which was consumed far in excess of its are normally eaten by Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus canadensis nelsoni), and the rela- vegetative composition. These had an tive value of these plants from a manager’s viewpoint based on the response elk have average ranking of 2.25 to 3.00. Valuable exhibited toward them. Plant species are classified as highly valuable, valuable, or least plants-one sought and readily eaten but valuable on the basis of their contribution to the diet in food habits studies where to a lesser extent than highly valuable they were recorded. A total of 159 forbs, 59 grasses, and 95 shrubs are listed as elk plants. Such plants made up a moderate forage and categorized according to relative value. part of the diet in food habits studies where encountered. Valuable plants had an average ranking of 1.50 to 2.24. Least Knowledge of the relative forage value elk food habits, and studies meeting the valuable plant-one eaten by elk but which of plants eaten by elk is basic to elk range following criteria were incorporated: (1) usually made up a minor part of the diet surveys, and to planning and evaluation Data must be original and derived from a in studies where encountered, or which of habitat improvement programs. -

Prescribed Fire and Cattle Grazing on an Elk Winter Range in Montana Author(S): Craig S

Prescribed Fire and Cattle Grazing on an Elk Winter Range in Montana Author(s): Craig S. Jourdonnais and Donald J. Bedunah Source: Wildlife Society Bulletin, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Autumn, 1990), pp. 232-240 Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Wildlife Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3782207 Accessed: 30-06-2015 23:20 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3782207?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and Wildlife Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Wildlife Society Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 166.7.157.176 on Tue, 30 Jun 2015 23:20:33 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Wildi. Soc. Bull. 18:232-240, 1990 PRESCRIBED FIRE AND CATTLE GRAZINGON AN ELK WINTER RANGEIN MONTANA CRAIG S. JOURDONNAIS,' School of Forestry, Universityof Montana, Missoula, MT 59812 DONALD J. BEDUNAH, School of Forestry, Universityof Montana, Missoula, MT 59812 The Sun RiverWildlife Management Area ityfor elk winteringon themanagement area, is a majorwinter range for elk (Cervuselaphus withoutreducing rough fescue production. -

2.5" Pot $3.50 4" Pot $6.00 Medium Tube $7.00 Large Tube $9.00 Quart $12

Pot Size Cost (per plant) 2.5" Pot $3.50 4" Pot $6.00 Medium tube $7.00 Large tube $9.00 Quart $12 Scientific Name Common Name Pot Size TREES Ohio Buckeye Aesculus glabra Large tube American Chestnut Castanea dentata Medium tube Northern Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Medium tube Common Persimmon Diospyros virginiana Medium tube Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Medium tube Black Cherry Prunus serotina Medium tube Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Medium tube Chestnut Oak Quercus montana Large tube Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii Medium tube Red Oak Quercus rubra Medium tube SHRUBS Black Chokeberry Aronia melanocarpa Quart Common Buttonbush Cephalanthus occidentalis Quart American Hazelnut Corylus americana Medium tube Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Quart SEDGES Plains Oval Sedge Carex brevior 2.5" Pot Cherokee sedge Carex cherokeensis 4" Pot Bristleaf Sedge Carex eburnea 4" Pot Palm Sedge Carex muskingumensis 2.5" Pot Plaintain Leafed sedge Carex plantaginea 4" Pot Rosy Sedge Carex rosea 2.5" Pot Long-beaked Sedge Carex sprengelii 2.5" Pot GRASSES Big Bluestem Andropogon gerardii 2.5" Pot Sideoats Grama Bouteloua curtipendula 2.5" Pot Blue Grama Bouteloua gracilis 2.5" Pot Sand Lovegrass Eragrostis trichodes 2.5" Pot Purple Tears Switchgrass Panicum virgatum 'Purple Tears' 4" Pot Ruby Ribbons Switchgrass Panicum virgatum Ruby Ribbons 4" Pot Summer Sunrise Switchgrass Panicum virgatum 'Summer sunrise' 4" Pot Indian Grass Sorghastrum nutans 2.5" Pot PERENNIALS Blue Giant Hyssop Agastache foeniculum 2.5" Pot Yellow Giant Hyssop Agastache nepetoides 2.5" Pot Purple Giant Hyssop Agastache scrophulariifolia 2.5" Pot Woman's Tobacco Antennaria plantaginifolia 2.5" Pot Swamp Milkweed Asclepias incarnata 2.5" Pot Butterfly Milkweed Asclepias tuberosa 2.5" Pot Canadian Milkvetch Astragalus canadensis 2.5" Pot Boltonia asteroides var. -

For Monarch Butterflies Why Monarchs? Why Oklahoma? Take Action!

WESTERN Oklahoma Plant List for Monarch Butterflies Why Monarchs? Why Oklahoma? Take Action! In the last decade, due to habitat loss and other Oklahoma is centrally located in the From Enid to Durant and Elk City to Tahlequah, factors, monarch butterfly populations have monarch migration flyway! now is the time (before it's too late) for us Okies to plummeted at an alarming rate. And they continue get our hands dirty and help the monarchs! to decline. Each spring, monarchs migrate north through Oklahoma and the Great Plains to Canada in Action 1 - Show your support by taking the pledge Since 1996, monarch colonies have declined 90%. search of milkweed plants on which to lay their to save the monarchs online at If all monarchs from the population high in the eggs. In the fall, they fly back through Oklahoma okiesformonarchs.org. mid-1990s were grouped onto football fields, the and the Great Plains south to Mexico to spend the area they covered has been reduced from 39 fields winter. Action 2 - Provide monarchs with habitat by to an area barely larger than one. planting milkweed and nectar plants on your In order for Monarchs to thrive, we Okies property. Did you know that Oklahoma has 26 Additionally, monarchs and other butterflies help must provide ample food, shelter and breeding different kinds of native milkweed plants and more polinate our crops. It is important to restore and grounds during both their migrations. than 79 monarch-friendly, native nectar plants? protect their habitat so we can continue to grow There's plenty to choose from! We made it easy our food. -

Ecological Checklist of the Missouri Flora for Floristic Quality Assessment

Ladd, D. and J.R. Thomas. 2015. Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora for Floristic Quality Assessment. Phytoneuron 2015-12: 1–274. Published 12 February 2015. ISSN 2153 733X ECOLOGICAL CHECKLIST OF THE MISSOURI FLORA FOR FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT DOUGLAS LADD The Nature Conservancy 2800 S. Brentwood Blvd. St. Louis, Missouri 63144 [email protected] JUSTIN R. THOMAS Institute of Botanical Training, LLC 111 County Road 3260 Salem, Missouri 65560 [email protected] ABSTRACT An annotated checklist of the 2,961 vascular taxa comprising the flora of Missouri is presented, with conservatism rankings for Floristic Quality Assessment. The list also provides standardized acronyms for each taxon and information on nativity, physiognomy, and wetness ratings. Annotated comments for selected taxa provide taxonomic, floristic, and ecological information, particularly for taxa not recognized in recent treatments of the Missouri flora. Synonymy crosswalks are provided for three references commonly used in Missouri. A discussion of the concept and application of Floristic Quality Assessment is presented. To accurately reflect ecological and taxonomic relationships, new combinations are validated for two distinct taxa, Dichanthelium ashei and D. werneri , and problems in application of infraspecific taxon names within Quercus shumardii are clarified. CONTENTS Introduction Species conservatism and floristic quality Application of Floristic Quality Assessment Checklist: Rationale and methods Nomenclature and taxonomic concepts Synonymy Acronyms Physiognomy, nativity, and wetness Summary of the Missouri flora Conclusion Annotated comments for checklist taxa Acknowledgements Literature Cited Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora Table 1. C values, physiognomy, and common names Table 2. Synonymy crosswalk Table 3. Wetness ratings and plant families INTRODUCTION This list was developed as part of a revised and expanded system for Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) in Missouri. -

3511320 Central Mixedgrass Prairie

LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting Model Biophysical Setting 3511320 Central Mixedgrass Prairie This BPS is lumped with: This BPS is split into multiple models: General Information Contributors (also see the Comments field) Date 1/10/2007 Modeler 1 Delbert M. [email protected] Reviewer Sam Fuhlendorf [email protected] Bassett du Modeler 2 Lee Elliott [email protected] Reviewer Modeler 3 Reviewer Vegetation Type Dominant Species Map Zone Model Zone BOBA3 Upland 35 Alaska Northern Plains SCSC Grassland/Herbaceous California N-Cent.Rockies General Model Sources NALE3 Great Basin Pacific Northwest Literature ERIN Great Lakes South Central Local Data BOGR2 Hawaii Southeast Expert Estimate BOCU Northeast S. Appalachians SONU2 Southwest PRGL2 Geographic Range This type historically occurs in western KS, western NE, eastern CO, northeastern NM, eastern TX panhandle into central TX, and along the western portion of OK proper. This BpS comprises the eastern half of MZ34 in ECOMAP sections 332F and 315C. This type occurs in the western half of MZ32 and in the northern half of MZ35 (west of Interstate-35). Biophysical Site Description This type occurs on sandy loam, loamey, or clayey upland sites of the southern Great Plains. In Texas and Oklahoma, elevations range from 915-275m (Wright and Bailey 1982). Precipitation ranges from 20-28in (Wright and Bailey 1982), although mixedgrass can occur on sites with up to 32in, and occurs mostly from May through September. Vegetation Description Historically, vegetation was generally dominated by midgrass, with some areas occupied by tallgrasses or short grasses, as an effect of grazing, edaphic and topographic conditions. (Species in order of dominance in boxes.) Dominant species include mostly midgrasses with some mix of tall and short grass - side oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), needlegrasses, little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Bothriochloa barbinodis, Nassella leucotricha and Eragrostis intermedia. -

Pityopsis Oligantha (Asteraceae) New to Texas

Holmes, W.C. and J.R. Singhurst. 2012. Pityopsis oligantha (Asteraceae) new to Texas. Phytoneuron 2012-110: 1–4. Published 5 December 2012. ISSN 2153 733X PITYOPSIS OLIGANTHA (ASTERACEAE) NEW TO TEXAS WALTER C. HOLMES Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas 76798-7388 [email protected] JASON R. SINGHURST Wildlife Diversity Program Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 [email protected] ABSTRACT Pityopsis oligantha , Large-flowered Goldenaster, is documented as new to Texas. The species was encoutered and collected in the West Gulf Coastal Plain Wetland Longleaf Pine Savannah of deep east Texas (Jasper County). KEY WORDS: Asteraceae, Pityopsis , Longleaf Pine savannah, Texas. In the Manual of the Vascular Plants of Texas, Correll and Johnston (1970) included Pityopsis oligantha (Chapm. ex Torr. & A. Gray) Small under the synonym Heterotheca oligantha (Chapm.) Harms within the treatment of that genus. They mentioned that the species was “not yet noted from Tex. but possibly to be encountered [italics inserted] in extreme e. cos.” Doubtless, the “record” of this species in the state originated here and was later included in Hatch et al. (1990) and Jones et al. (1997), both being checklists of the vascular plants of the state. It is not known why Correll and Johnson would consider the species as possibly occurring in Texas, for at that time (pre- 1970), the distribution of P. oligantha was known to be west Florida and adjacent Alabama and Georgia (Small 1933). The lack of a supporting specimen has resulted in the species no longer being included as a part of the Texas flora (Cronquist 1980; Turner et al.