Messages, Signs, and Meanings: a Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication Theory, 3Rdedition by Marcel Danesi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Seventeenth-Century Doublet from Scotland

Edinburgh Research Explorer A Seventeenth-Century Doublet from Scotland Citation for published version: Wilcox, D, Payne, S, Pardoe, T & Mikhaila, N 2011, 'A Seventeenth-Century Doublet from Scotland', Costume, vol. 2011, no. 45, pp. 39-62. https://doi.org/10.1179/174963011X12978768537537 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1179/174963011X12978768537537 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Costume Publisher Rights Statement: © Wilcox, D., Payne, S., Pardoe, T., & Mikhaila, N. (2011). A Seventeenth-Century Doublet from Scotland. Costume , 2011(45), 39-62 doi: 10.1179/174963011X12978768537537 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 © Wilcox, D., Payne, S., Pardoe, T., & Mikhaila, N. (2011). A Seventeenth-Century Doublet from Scotland. Costume , 2011(45), 39-62 doi: 10.1179/174963011X12978768537537 A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY DOUBLET FROM SCOTLAND By SUSAN PAYNE, DAVID WILCOX, TUULA PARDOE AND NINYA MIKHAILA. In December 2004 a local family donated a cream silk slashed doublet to Perth Museum and Art Gallery.i Stylistically the doublet is given a date between 1620 and 1630 but the family story is that it was a gift to one of their ancestors about the time of the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Replica Styles from 1795–1929

Replica Styles from 1795–1929 AVENDERS L REEN GHistoric Clothing $2.00 AVENDERS L REEN GHistoric Clothing Replica Styles from 1795–1929 Published by Lavender’s Green © 2010 Lavender’s Green January 2010 About Our Historic Clothing To our customers ... Lavender’s Green makes clothing for people who reenact the past. You will meet the public with confidence, knowing that you present an ac- curate picture of your historic era. If you volunteer at historic sites or participate in festivals, home tours, or other historic-based activities, you’ll find that the right clothing—comfortable, well made, and accu- rate in details—will add so much to the event. Use this catalog as a guide in planning your period clothing. For most time periods, we show a work dress, or “house dress.” These would have been worn for everyday by servants, shop girls, and farm wives across America. We also show at least one Sunday gown or “best” dress, which a middle-class woman would save for church, weddings, parties, photos, and special events. Throughout the catalog you will see drawings of hats and bonnets. Each one is individually designed and hand-made; please ask for a bid on a hat to wear with your new clothing. Although we do not show children’s clothing on most of these pages, we can design and make authentic clothing for your young people for any of these time periods. Generally, these prices will be 40% less than the similar adult styles. The prices given are for a semi-custom garment with a dressmaker- quality finish. -

Medieval Roslin – What Did People Wear?

Fact Sheet 4 Medieval Roslin – What did people wear? Roslin is in the lowlands of Scotland, so you would not see Highland dress here in the Middle Ages. No kilts or clan tartans. Very little fabric has survived from these times, so how do we find out what people did wear? We can get some information from bodies found preserved in peat bogs. A bit gruesome, but that has given us clothing, bags and personal items. We can also look at illustrated manuscripts and paintings. We must remember that the artist is perhaps making everyone look richer and brighter and the people being painted would have their best clothes on! We can also look at household accounts and records, as they often have detailed descriptions. So over the years, we have built up This rich noblewoman wears a patterned satin dress some knowledge. and a expensive headdress,1460. If you were rich, you could have all sorts of wonderful clothes. Soldiers returning from the crusades brought back amazing fabrics and dyes from the East. Trade routes were created and soon fine silks, satins, damasks, brocades and velvets were readily available – if you could afford them! Did you know? Clothing was a sign of your status and there • Headdresses could be very were “sumptuary laws“ saying what you could elaborate. Some were shaped and could not wear. Only the wives or daughters like hearts, butterflies and even of nobles were allowed to wear velvet, satin, church steeples! sable or ermine. Expensive head dresses or veils were banned for lower class women. -

Storage Treasure Auction House (CLICK HERE to OPEN AUCTION)

09/28/21 04:44:04 Storage Treasure Auction House (CLICK HERE TO OPEN AUCTION) Auction Opens: Tue, Nov 27 5:00am PT Auction Closes: Thu, Dec 6 2:00pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0500 18k Sapphire .38ct 2Diamond .12ct ring (size 9) 0533 Watches 0501 925 Ring size 6 1/2 0534 Watches 0502 925 Chain 0535 Watches 0503 925 Chain 0536 Watches 0504 925 Bracelet 0537 Watches 0505 925 Tiffany company Braceltes 0538 Watch 0506 925 Ring size 7 1/4 0539 Watch 0507 925 Necklace Charms 0540 Watches 0508 925 Chain 0541 Watches 0509 925 Silver Lot 0542 Kenneth Cole Watch 0510 925 Chain 0543 Watches 0511 925 Silver Lot 0544 Pocket Watch (needs repair) 0512 925 Necklace 0545 Pocket Watch 0513 10K Gold Ring Size 7 1/4 0546 Earrings 0514 London Blue Topaz Gemstone 2.42ct 0547 Earrings 0515 Vanity Fair Watch 0548 Earrings 0516 Geneva Watch 0549 Earrings 0517 Watches 0550 Earrings 0518 Jordin Watch 0551 Earrings 0519 Fossil Watch 0552 Earrings 0520 Watches 0553 Necklace 0521 Watches & Face 0554 Necklaces 0522 Necklace 0555 Necklace Charms 0523 Watches 0556 Necklace 0524 Kenneth Cole Watch 0557 Necklaces 0525 Pennington Watch 0558 Belly Dancing Jewelry 0526 Watch 0559 Bracelet 0527 Watches 0560 Horseshoe Necklace 0528 Watches 0561 Beaded Necklaces 0529 Watch Parts 0562 Mixed Jewelry 0530 Watches 0563 Necklace 0531 Watch 0564 Earrings 0532 Watch 0565 Chains 1/6 09/28/21 04:44:04 Lot Title Lot Title 0566 Necklace 0609 Chains 0567 Necklace 0610 Necklace 0568 Necklace 0611 Necklace 0569 Necklace 0612 Bracelets 0570 Necklace 0613 Necklace With Black Hills gold Charms 0571 -

The Bread-Winners

READWINN'^t' -\ ^^?^!lr^^ <^.li i^w LaXi Digitized by the Internet Arcinive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/breadwinnerssociOOhayj THE BREAD-WINNERS 21 Social Sttttra NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE Ck)p7right, 1883, by The Century Company. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, by HARPER & BROTHERS, In the Oflace of the Librarian of Congress, at "Washingtoa All righit teterved. THE BREAD-WINNEUS. A MORNING CALL. A French clock on the mantel-piece, framed of brass and crystal, wliicli betrayed its inner structure as tlie transparent sides of some insects betray tlieir vital processes, struck ten with the mellow and lingering clangor of a distant cathedral bell. A gentleman, who was seated in front of the lire read- ing a newspaper, looked up at the clock to see what hour it was, to save himself the trouble of counting the slow, musical strokes. The eyes he raised were light gray, with a blue glint of steel in them, shaded by lashes as black as jet. The hair was also as black as hair can be, and was parted near the middle of his forehead. It was inclined to curl, but had not the length required by this inclination. The dark brown mustache was the only ornament the razor had spared on the wholesome face, the outline of which was clear and keen. The face suited the hands—it had the refinement and gentle- ness of one delicately bred, and the vigorous lines and color of one equally at home in field and court; 6 THE BREAD-WINNERS. -

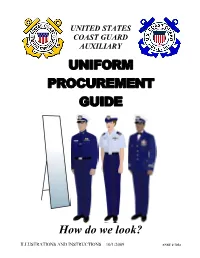

Uniform Procurement Guide

UNITED STATES COAST GUARD AUXILIARY UNIFORM PROCUREMENT GUIDE How do we look? ILLUSTRATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS – 10/1/2009 ANSC # 7053 RECORD OF CHANGES # DATE CHANGE PAGE 1. Insert “USCG AUXILIARY TUNIC OVERBLOUSE” information page with size chart. 19 2. Insert the Tunic order form page. 20 3. Replace phone and fax numbers with “TOLL FREE: (800) 296-9690 FAX: (877) 296-9690 and 26 1 7/2006 PHONE: (636) 685-1000”. Insert the text “ALL WEATHER PARKA I” above the image of the AWP. 4. Insert the NEW ALL WEATHER II OUTERWEAR SYSTEM information page. 27 5. Insert the RECEIPT FOR CLOTHING AND SMALL STORES form page. 28 1. Insert additional All Weather Parka I information. 26 2 11/2006 2. Insert All Weather Parka II picture. 27 1. Replace pages 14-17 with updated information. 14-17 3 3/2007 2. Insert UDC Standard Order Form 18 1. Change ODU Unisex shoes to “Safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes***” 4 4/2007 6, 8 2. Add a footnote for safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes 5 2/2008 1. Remove ODU from Lighthouse Uniform Company Inventory 25 1. Reefer and overcoat eliminated as outerwear but can be worn until unserviceable 6-10 6 3/2008 2. Remove PFD from the list of uniform items that may be worn informally 19 3. Update description of USCG Auxiliary Tunic Over Blouse Option for Women 21 1. Remove “Long”, “Alpha” and “Bravo” terminology from Tropical Blue and Service Dress Blue 7 6/4/2009 All uniforms 1. Sew on vendors for purchase of new Black “A” and Aux Op authorized 32 8 10/2009 2. -

Attire Tailoring Fine Formal Hire

Attire Tailoring fine formal hire www.attiretailoring.co.uk Here at Attire Tailoring we know more than anybody that it is so imperative to look and feel your outright best on this huge day. Getting everybody in co-ordinating outfits is simple with our broad hirewear assortment, accessible in pretty much every size. With top of the line formal outfits and coordinating accessories, you’ll discover all that you need to put your best self forward, with costs from just £35 per outfit. View our wide scope of styles and shading palettes on the web and build your look using our intelligent Outfit Builder. With our totally online service you can arrange everthing without the need to visit a store . With our online service, we’ll send you the style of your choice for a two day trial in your own home, months before the wedding. Plan your wedding rapidly and where needed with our online assistance. With over 20 years of hirewear experience everything you need is taken care of. The choice is yours... Hire is the flexible choice. It doesn’t matter if it’s 1 or 100 guests, we have the sizes to fit the whole party - even the little ones! Hire is the convenient choice. Your wedding party can be located any- where in the UK and we’ll make sure all outfits are delivered up to a full week before the function date. Travelling to the UK from abroad? We deliver to hotels too! Hire is the sustainable/ethical choice. Renting is recylcing. Go on! book your fitting atwww.attire-tailoring.co.uk *The Try On service is only available on selected months. -

Hollands (800) 232-1918 2012 Fine Western Jewelry Since 1936 Fax (325) 653-3963

RETAIL (325) 655-3135 PRICELIST HOLLANDS (800) 232-1918 2012 FINE WESTERN JEWELRY SINCE 1936 FAX (325) 653-3963 Page 2&3 SPUR JEWELRY Regular Junior Spurette Necklace Spurette Earrings 1 3/8" tall 1" tall 5/8" tall 5/8" tall R-P-A $185 J-P-A $185 SN-P-A $160 SE-P-A $ 320 R-P-B 230 J-P-B 230 SN-P-B 190 SE-P-B 380 R-P-C 260 J-P-C 260 SN-P-C 215 SE-P-C 415 R-HC-A 215 J-HC-A 215 SN-HC-A 175 SE-HC-A 350 R-HC-B 260 J-HC-B 260 SN-HC-B 205 SE-HC-B 410 R-HC-C 290 J-HC-C 290 SN-HC-C 230 SE-HC-C 460 R-GO-A 270 J-GO-A 270 SN-GO-A 230 SE-GO-A 460 R-GO-B 320 J-GO-B 320 SN-GO-B 260 SE-GO-B 520 R-GO-C 350 J-GO-C 350 SN-GO-C 290 SE-GO-C 580 R-G-A 1100 J-G-A 900 SN-G-A 625 SE-G-A 1250 R-G-B 1250 J-G-B 1050 SN-G-B 725 SE-G-B 1450 R-G-C 1250 J-G-C 1050 SN-G-C 725 SE-G-C 1450 Spur necklace is price above plus chain. Spur necklace is price above plus chain. Spurette pin is price of spurette necklace plus $35.00. Cufflinks are price above multiplied by two. -

JEWELLERY TREND REPORT 3 2 NDCJEWELLERY TREND REPORT 2021 Natural Diamonds Are Everlasting

TREND REPORT ew l y 2021 STATEMENT J CUFFS SHOULDER DUSTERS GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY GEOMETRIC DESIGNS PRESENTED BY THE NEW HEIRLOOM CONTENTS 2 THE STYLE COLLECTIVE 4 INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 8 STATEMENT CUFFS IN AN UNPREDICTABLE YEAR, we all learnt to 12 LARGER THAN LIFE fi nd our peace. We seek happiness in the little By Anaita Shroff Adajania things, embark upon meaningful journeys, and hold hope for a sense of stability. This 16 SHOULDER DUSTERS is also why we gravitate towards natural diamonds–strong and enduring, they give us 20 THE STONE AGE reason to celebrate, and allow us to express our love and affection. Mostly, though, they By Sarah Royce-Greensill offer inspiration. 22 GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY Our fi rst-ever Trend Report showcases natural diamonds like you have never seen 26 HIS & HERS before. Yet, they continue to retain their inherent value and appeal, one that ensures By Bibhu Mohapatra they stay relevant for future generations. We put together a Style Collective and had 28 GEOMETRIC DESIGNS numerous conversations—with nuance and perspective, these freewheeling discussions with eight tastemakers made way for the defi nitive jewellery 32 SHAPESHIFTER trends for 2021. That they range from statement cuffs to geometric designs By Katerina Perez only illustrates the versatility of their central stone, the diamond. Natural diamonds have always been at the forefront of fashion, symbolic of 36 THE NEW HEIRLOOM timelessness and emotion. Whether worn as an accessory or an ally, diamonds not only impress but express how we feel and who we are. This report is a 41 THE PRIDE OF BARODA product of love and labour, and I hope it inspires you to wear your personality, By HH Maharani Radhikaraje and most importantly, have fun with jewellery. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear Through the Ages FCC TP V2 930 3/5/04 3:55 PM Page 3

FCC_TP_V2_930 3/5/04 3:55 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V2_930 3/5/04 3:55 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 2: Early Cultures Across2 the Globe SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos.