Review of Atlas of the New West: Portrait of a Changing Region Edited by William Riebsame with Maps by James Robb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Far West Region

CHAPTER FIVE Far West Region California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Nevada, Idaho, Pacific Islands North 0 100 200 Kilometers 0 100 200 Miles WASHINGTON OREGON IDAHO NEVADA ALASKA CALIFORNIA HAWAII United States Territories AMERICAN SAMOA GUAM Faces and Places of Cooperative Conservation 113 COOPERATIVE CONSERVATION CASE STUDY California Tribal Partnerships PHOTO BY KEN WILSON Traditional Native American Values Support Forest Management Location: California Project Summary: A unique blend of traditional Native American practices and today’s science preserves native customs and contributes to forest health. Children practice indigenous basket weaving techniques at a camp in California that sustains traditional cultural practices. Resource Challenge working with weavers, volunteers manage forests for future Over thousands of years, native peoples learned to manage the land, basketry materials, thinning heavy fuels and building fi re breaks using practices such as controlled burns to create a healthy landscape. to prepare for Forest Service controlled burns. More than 500 The USDA Forest Service in California is consulting and collaborating participants have volunteered 2,800 hours, saving $25,000 in with tribes on more than 50 projects. Several are government-to- taxpayer dollars. The National Advisory Council on Historic government agreements, with both entities pledging to cooperatively Preservation and the Governor of California have both awarded protect and restore the ecological health of land. Restoring and the project for enhancing traditional forest management in sustaining culturally important plants and re-introducing fi re as a tool California. for forest renewal are two of the primary objectives. • The Maidu Cultural Development Group Stewardship Project (MCDG) Examples of Key Partners is integrating traditional land practices with modern resource USDA Forest Service, Karuk Indigenous Weavers, California Indian management on 2,100 acres of the Plumas National Forest. -

States & Capitals

United States West Region States & Capitals Maps & Flashcards This product contains 3 maps of the West Region of the United States. Study guide map labeled with the states and capitals (which can also be used as an answer key) Blank map with a word bank of the states and capitals Blank map without word bank Also included are 3 different versions of flashcards to study states and/or capitals. State shaded within the region on the front with state name on the back State name and outline on the front with capital on the back State outline on the front with state name and capital on the back To create flashcards: print, fold along solid line, cut on dotted lines. I glue the folded halves together, and then laminate for longevity. West: Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming Correlates to Massachusetts History & Social Science Learning Standard 4.10 I hope you find this product useful in your classroom. If you have any questions or comments, please contact me at [email protected]. 2013-2014 Copyright Mrs LeFave Name Date West States & Capitals Map Study Guide ALASKA Juneau * WASHINGTON *Olympia *Helena *Salem MONTANA OREGON *Boise IDAHO WYOMING Cheyenne Sacramento * * * *Carson City Salt Lake City *Denver NEVADA UTAH COLORADO CALIFORNIA * Honolulu HAWAII 2013-2014 Copyright Mrs LeFave Name Date West States & Capitals Map ALASKA Boise CALIFORNIA Carson City COLORADO Cheyenne HAWAII Denver IDAHO Helena MONTANA Honolulu NEVADA Juneau OREGON Olympia UTAH Sacramento WASHINGTON Salem -

TRICARE West Region Provider Handbook Will Assist You in Delivering TRICARE Benefits and Services

TRICARE® West Region Provider Handbook Your guide to TRICARE programs, policies and procedures January 1–December 31, 2019 Last updated: July 1, 2019 An Important Note about TRICARE Program Information This TRICARE West Region Provider Handbook will assist you in delivering TRICARE benefits and services. At the time of publication, July 1, 2019, the information in this handbook is current. It is important to remember that TRICARE policies and benefits are governed by public law, federal regulation and the Government’s amendments to Health Net Federal Services, LLC’s (HNFS’) managed care support (MCS) contract. Changes to TRICARE programs are continually made as public law, federal regulation and HNFS’ MCS contract are amended. For up-to-date information, visit www.tricare-west.com. Contracted TRICARE providers are obligated to abide by the rules, procedures, policies and program requirements as specified in this TRICARE West Region Provider Handbook, which is a summary of the TRICARE regulations and manual requirements related to the program. TRICARE regulations are available on the Defense Health Agency (DHA) website at www.tricare.mil. If there are any discrepancies between the TRICARE West Region Provider Handbook and TRICARE manuals (Manuals), the Manuals take precedence. Using This TRICARE West Region Provider Handbook This TRICARE West Region Provider Handbook has been developed to provide you and your staff with important information about TRICARE, emphasizing key operational aspects of the program and program options. This handbook will assist you in coordinating care for TRICARE beneficiaries. It contains information about specific TRICARE programs, policies and procedures. TRICARE program changes and updates may be communicated periodically through TRICARE Provider News and the online publications. -

The Winter Season December 1, 1990-February 28, 1991

STANDARDABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE REGIONALREPORTS Abbreviations used in placenames: THE In mostregions, place names given in •talictype are counties. WINTER Other abbreviations: Cr Creek SEASON Ft. Fort Hwy Highway I Island or Isle December1, 1990-February28, 1991 Is. Islands or Isles Jct. Junction km kilometer(s) AtlanticProvinces Region 244 TexasRegion 290 L Lake Ian A. McLaren GregW. Lasleyand Chuck Sexton mi mile(s) QuebecRegion 247 Mt. Mountain or Mount YvesAubry, Michel Gosselin, Idaho/ Mts. Mountains and Richard Yank Western Montana Region 294 N.F. National Forest ThomasH. Rogers 249 N.M. National Monument New England Blair Nikula MountainWest Region 296 N.P. National Park HughE. Kingety N.W.R. NationalWildlife Refuge Hudson-DelawareRegion 253 P P. Provincial Park WilliamJ. Boyle,Jr., SouthwestRegion 299 Pen. Peninsula Robert O. Paxton, and Arizona:David Stejskal Pt. Point (not Port) David A. Culter andGary H. Rosenberg New Mexico: R. River MiddleAtlantic Coast Region 258 Sartor O. Williams III Ref. Refuge HenryT. Armistead andJohn P. Hubbard Res. Reservoir(not Reservation) S P. State Park Sonthern Atlantic AlaskaRegion 394 262 W.M.A. WildlifeManagement Area CoastRegion T.G. Tobish,Jr. and (Fall 1990 Report) M.E. Isleib HarryE. LeGrand,Jr. Abbreviations used in the British Columbia/ names of birds: Florida Region 265 Yukon Region 306 Am. American JohnC. Ogden Chris Siddle Corn. Common 309 E. Eastern OntarioRegion 268 Oregon/WashingtonRegion Ron D. Weir (Fall 1990 Report) Eur. Europeanor Eurasian Bill Tweit and David Fix Mt. Mountain AppalachianRegion 272 N. Northern GeorgeA. Hall Oregon/WashingtonRegion 312 S. Southern Bill Tweit andJim Johnson W. Western Western Great Lakes Region 274 DavidJ. -

Nonstop-Denver

Nonstop-Denver Directo Denver America’s favorite connecting hub... where the Rocky Mountains meet the world. 1 2 Perfectly Positioned Nonstop destinations served from DEN To Fairbanks To Anchorage Edmonton Vancouver Calgary Bellingham Saskatoon Regina Seattle Winnipeg Spokane Kalispell Great Falls Williston Pasco Missoula Minot Portland Devils Lake Helena Bismarck Dickinson Jamestown Eugene Bozeman Billings Fargo Redmond Medford Cody Sheridan Minneapolis Traverse City Boise Reykjavik Idaho Falls Gillette Boston Sun Valley Jackson Rapid City Toronto Pierre Madison Grand Casper Providence Riverton Sioux Falls Rapids Denver International Airport is located in the geographic center of Milwaukee Detroit Hartford Chadron Cedar Rapids New York-JFK & LGA Alliance Sioux City Chicago-ORD & MDW Cleveland Newark Rock Springs Des Moines Laramie Scottsbluff Pittsburgh Philadelphia the United States and is a critical link for business and leisure travelers Sacramento Salt Lake City Cheyenne Moline Akron/Canton Reno North Platte Omaha Harrisburg Wilmington Oakland Steamboat Springs Kearney Peoria Vail McCook Lincoln Columbus Baltimore San Francisco Mammoth Aspen Bloomington Indianapolis Dayton Washington IAD around the world. San Jose Grand Cincinnati -DCA Junction Gunnison DENVER Fresno Colorado Hays Kansas City St. George Montrose Springs Newport News Telluride St. Louis Las Vegas Pueblo Louisville • 5th busiest commercial passenger airport in U.S. Tokyo Bakersfield Page Cortez Dodge City Durango Alamosa Wichita Farmington Raleigh/Durham Santa Barbara -

2012 WFTDA West Playoffs Hospitality Guide

WFTDA 2012 West Region Playoffs Hospitality Guide September 21 - 23, Richmond CA Craneway Pavilion Hosted by B.ay A.rea D.erby Girls Craneway Pavilion Where we skate 1414 Harbour Way South, Richmond, CA 94804 craneway.com Craneway Pavilion is a 45,000 sq ft world- class, sustainably designed event, concert and production facility set on 25 waterfront acres that provide an awe-inspiring panorama of the Bay and the San Francisco skyline. Originally a Ford Motors Assembly Plant, the venue is now on the National Register of Historic Places while offering state-of-the-art amenities – and of course, a landing pad for those of you who plan to arrive by helicopter. Parking There is an attended lot across from the venue for $10/day. Additionally, there are a couple hundred free spots on the street available after 5pm on Friday and all day on the weekend. Security There will be hired security personnel and volunteer security staff from the B.ay A.rea D.erby Girls to attend to crowd control and general security matters. Nonetheless, you are advised not to leave valuables unattended as neither WFTDA, B.ay A.rea D.erby Girls nor the Craneway Pavilion can be responsible for loss, damage or theft of your belongings. Any property you bring to the event is at your own risk. Food and Beverage The Craneway Pavilion has a full restaurant on-site, the BoilerHouse Restaurant, but allows for independent food vendors to come into the venue to provide concessions. The B.ay A.rea D.erby Girls have arranged for food trucks and vendors to come to the venue for the tournament, with such local favorites like Donna’s Tamales, Fist of Flour Pizza, and Liba Falafel. -

Changing Compensation Costs in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area

For Release: Tuesday, August 03, 2021 21-1451-SAN WESTERN INFORMATION OFFICE: San Francisco, Calif. Technical information: (415) 625-2270 [email protected] www.bls.gov/regions/west Media contact: (415) 625-2270 Changing Compensation Costs in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area – June 2021 Compensation costs for private industry workers increased 4.5 percent in the Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA Combined Statistical Area (CSA) for the year ended June 2021, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Regional Commissioner Chris Rosenlund noted that one year ago, Los Angeles experienced an annual gain of 3.5 percent in compensation costs. (See chart 1 and table 1.) .) Locally, wages and salaries, the largest component of compensation costs, advanced at a 5.4-percent pace for the 12-month period ended June 2021. (See chart 2.) Nationwide, compensation costs increased 3.1 percent and wages and salaries rose 3.5 percent over the same period. Chart 1. Twelve-month percent changes in total compensation for private industry workers in the United States and Los Angeles, not seasonally adjusted Quarter Los Angeles United States Jun 2019....................................................................................................... 3.4 2.6 Sep ............................................................................................................... 3.7 2.7 Dec ............................................................................................................... 3.4 2.7 Mar .............................................................................................................. -

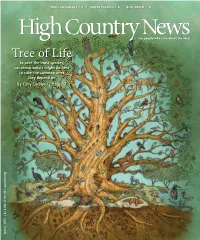

Tree of Life to Save the Most Species, Conservationists Might Do Best to Save the Common Ones They Depend on by Cally Carswell | Page 12 June 8, 2015 | $5 | Vol

TOXIC CHEMICALS | 5 | WATER LEASING | 6 | BULL TROUT | 8 High Country ForN people whoews care about the West Tree of Life To save the most species, conservationists might do best to save the common ones they depend on By Cally Carswell | Page 12 June 8, 2015 | $5 | Vol. 47 No. 10 | www.hcn.org 10 No. 47 | $5 Vol. June 8, 2015 CONTENTS Editor’s note The precious common Imagine a white burqa crossed with a beekeeper’s suit. At the end of one arm protrudes a pterodactyl-esque puppet head with a long bill, a blazing red pate and cheeks streaked a vivid black. But its golden eyes are flat and unmoving, like those of a specimen in a museum diorama. If you’re a whooping crane chick raised in captivity at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Laurel, Maryland, this is the costume worn by the human pretending to be your mom. Because your species numbered around 20 in 1941, scientists carefully selected your biological parents to avoid genetic problems. Once you hatch, your surrogate “crane” teaches you, by example, to eat crane kibble, and to swim in a pool and dash across the grass so that your legbones develop correctly. When you’re old enough, she teaches you to follow an ultralight aircraft on your first migratory flight to Piñon pines on a ridge in Sunset Crater Volcano National Florida’s Gulf Coast. She shapes you, in essence, to Monument, where Northern Arizona University scientists are an approximation of wildness, hoping that you will studying genetic diversity in plants. -

Changing Compensation Costs in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area

For Release: Tuesday, November 03, 2020 20-2071-SAN WESTERN INFORMATION OFFICE: San Francisco, Calif. Technical information: (415) 625-2270 [email protected] www.bls.gov/regions/west Media contact: (415) 625-2270 Changing Compensation Costs in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area – September 2020 Total compensation costs for private industry workers increased 3.3 percent in the Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, Ariz. metropolitan area for the year ended September 2020, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Assistant Commissioner for Regional Operations Richard Holden noted that one year ago, Phoenix experienced an annual gain of 3.6 percent in compensation costs. Locally, wages and salaries, the largest component of compensation costs, advanced at a 3.8-percent pace for the 12-month period ended September 2020. Nationwide, total compensation costs increased 2.4 percent and wages and salaries rose 2.7 percent from September 2019 to September 2020. (See chart 1 and table 1.) Phoenix is 1 of 15 metropolitan areas in the United States and 1 of 4 areas in the West region of the country for which locality compensation cost data are now available. Among these 15 largest areas, over-the-year percentage changes in the cost of compensation ranged from 3.6 percent in Washington to 1.5 percent in Miami in September 2020; for wages and salaries, San Jose registered the largest increase (4.0 percent) while Miami registered the smallest (1.6 percent). (See chart 2.) The annual increase in compensation costs in Phoenix was 3.3 percent in September 2020, compared to changes that ranged from 3.5 to 2.6 percent in the three other metropolitan areas in the West (Los Angeles, San Jose, and Seattle). -

CURRENT Aafs.Pdf

AREA DEFINITIONS USED BY FY2015 ANNUAL ADJUSTMENT FACTORS ALABAMA (SOUTH) All Counties in Alabama use the South Region AAF. ALASKA (WEST) CPI AREAS: BOROUGHS Anchorage, AK MSA Metropolitan Area Components: Anchorage, AK HMFA Anchorage Matanuska-Susitna Borough, AK HMFA Matanuska-Susitna All other Boroughs use the West Region AAF. ARIZONA (WEST) CPI AREAS: COUNTIES Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ MSA Maricopa, Pinal All other Counties use the West Region AAF. ARKANSAS (SOUTH) All Counties in Arkansas use the South Region AAF. CALIFORNIA (WEST) CPI AREAS: COUNTIES Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA MSA Metropolitan Area Components: Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA HMFA Los Angeles Orange County, CA HMFA: Orange Napa, CA MSA Napa Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA MSA Ventura Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA MSA: Riverside, San Bernardino San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA MSA: San Diego San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA MSA Metropolitan Area Components: Oakland-Fremont, CA HMFA Alameda, Contra Costa San Francisco, CA HMFA Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo. San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA MSA Metropolitan Area Components: San Benito County, CA HMFA San Benito San Jose-Sunnydale-Santa Clara, CA HMFA Santa Clara Santa Cruz-Watsonville, CA MSA: Santa Cruz Santa Rosa-Petaluma, CA MSA: Sonoma Vallejo-Fairfield, CA MSA: Solano All other Counties in California use the West Region AAF. 11 AREA DEFINITIONS USED BY FY2015 ANNUAL ADJUSTMENT FACTORS TENNESSEE (SOUTH) All Counties in Tennessee use the South Region AAF. TEXAS (SOUTH) CPI AREAS: COUNTIES Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX MSA Metropolitan Area Components: Dallas, TX HMFA: Collin, Dallas, Delta, Denton, Ellis, Hunt, Kaufman, Rockwall. -

Space, Nation, and the Triumph of Region: a View of the World from Houston

Space, Nation, and the Triumph of Region: A View of the World from Houston Cameron Blevins For this article’s accompanying online component, see Cameron Blevins, “Min- ing and Mapping the Production of Space,” http://spatialhistory.stanford.edu/ viewoftheworld. On a rainy spring evening in 1898 the Texas newspaper editor Rienzi Johnston found himself in Chicago’s Grand Pacifc Hotel for the annual banquet of the Associated Press (ap). Johnston and eighty-seven fellow editors from across the country dined alongside two full-size printing presses built out of fowers and candy while seated at tables ar- ranged to form the initials ap. Over little-neck clams and roast snipe they listened to a series of speeches on the defning issues of the day. A prominent lawyer defended the As- sociated Press and its powerful national news syndicate from charges of monopoly, while a string of boisterous toasts celebrated the recent outbreak of war between the United States and Spain. In a ft of patriotism, one southern editor rose from his chair to declare that three decades removed from a bloody civil war, “Our People: they know no North, no South, no East, no West.” Johnston was no stranger to national integration. Tis editor of a midsize regional paper served as Texas’s delegate to the Democratic National Committee, briefy flled a vacated seat in the U.S. Senate, and was a rising leader within the ap’s ranks. Johnston moved comfortably in a web of national associations and afli- ations that extended well beyond his ofce in Houston and the carefully arranged tables of the Chicago banquet hall.1 Cameron Blevins is a doctoral candidate in history at Stanford University. -

July/August 98 Vol

THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Slain NPS Ranger Mourned, 2 Memorial Fund for Kolodski Children PEOPLE Endangered Joseph Kolodski Legacy LAND She was denigrated by some as an emotional woman whose exposé caused unnecessary alarm during the Cold War and whose polemic earned the unmitigated hostility of the agri-chemical industry. But Rachel Carson, who found her literary voice as a Fish and Wildlife Service science editor, WATERWATER was honored by the nation and the world for changing the course of environmental history. &July/August 98 Vol. 5, No. 6 Why, then, is her legacy being lost? 16-17 SCIENCE & STEWARDSHIP Environmental & Human Health: USGS brings science to bear on public health problems caused by evironmental degradation,12 El Niño’s Wake: Hit by the weather event of the century, NPS units pull together to repair damage, 10 Spectacled Eiders: FWS biologists remain puzzled by endangered duck’s continued decline in the Bering Sea ecosystem, 21 Black Hills Birding: Reclamation research pact with American Birding Association to develop 21 public birding sites in West, 29 WORKING WITH AMERICA Environmental Justice: Office of Environmental Policy and Compliance helps disadvantaged communities develop healthier environments and living conditions, 5 National Lakes: States and local jurisdictions seek greater role in recreation study of federal lakes, 8 Teeing off for Minorities: BLM and the World Golf Federation promote opportunity in golf industry for minorities, urban youth, 22 Native American Fish & Wildlife: San Carlos Apache