1. Aims 2. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alien and Invasive Species of Harmful Insects in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Alien and invasive species of harmful insects in Bosnia and Herzegovina Mirza Dautbašić1,*, Osman Mujezinović1 1 Faculty of Forestry University in Sarajevo, Chair of Forest Protection, Urban Greenery and Wildlife and Hunting. Zagrebačka 20, 71000 Sarajevo * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: An alien species – animal, plant or micro-organism – is one that has been introduced as a result of human activity to an area it could not have reached on its own. In cases where the foreign species expands in its new habitat, causing environmental and economic damage, then it is classified as invasive. The maturity of foreign species in the new area may also be influenced by climate changes. The detrimental effect of alien species is reflected in the reduction of biodiversity as well as plant vitality. A large number of alien species of insects are not harmful to plants in new habitats, but there are also those that cause catastrophic consequences to a significant extent. The aim of this paper is to present an overview of newly discovered species of insects in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The research area, for this work included forest and urban ecosystems in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina. For the purposes of this paper, an overview of the species found is provided: /HSWRJORVVXVRFFLGHQWDOLV Heidemann; (Hemiptera: Coreidae) - The western conifer seed bug, found at two sites in Central Bosnia, in 2013 and 2015; $UJHEHUEHULGLVSchrank; (Hymenoptera: Argidae) - The berberis sawfly, recorded in one locality (Central Bosnia), in 2015; -

Prioritising the Management of Invasive Non-Native Species

PRIORITISING THE MANAGEMENT OF INVASIVE NON-NATIVE SPECIES Olaf Booy Thesis submitted to the School of Natural and Environmental Sciences in fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University October 2019 Abstract Invasive non-native species (INNS) are a global threat to economies and biodiversity. With large numbers of species and limited resources, their management must be carefully prioritised; yet agreed methods to support prioritisation are lacking. Here, methods to support prioritisation based on species impacts, pathways of introduction and management feasibility were developed and tested. Results provide, for the first time, a comprehensive list of INNS in Great Britain (GB) based on the severity of their biodiversity impacts. This revealed that established vertebrates, aquatic species and non-European species caused greater impacts than other groups. These high impact groups increased as a proportion of all non-native species over time; yet overall the proportion of INNS in GB decreased. This was likely the result of lag in the detection of impact, suggesting that GB is suffering from invasion debt. Testing methods for ranking the importance of introduction pathways showed that methods incorporating impact, uncertainty and temporal trend performed better than methods based on counts of all species. Eradicating new and emerging species is one of the most effective management responses; however, practical methods to prioritise species based both on their risk and the feasibility of their eradication are lacking. A novel risk management method was developed and applied in GB and the EU to identify not only priority species for eradication and contingency planning, but also prevention and long term management. -

Leaf Beetle Larvae

Scottish Beetles BeesIntroduction and wasps to Leaf Beetles (Chrysomelidae) There are approximately 281 species of leaf beetles in the UK. This guide is an introduction to 17 species found in this family. It is intended to be used in combination with the beetle anatomy guide and survey and recording guides. Colourful and often metallic beetles, where the 3rd tarsi is heart shaped. Species in this family are 1-18mm and are oval or elongated oval shaped. The plants each beetle is found on are usually key to their identification. Many of the species of beetles found in Scotland need careful examination with a microscope to identify them. This guide is designed to introduce some of the leaf beetles you may find and give some key Dead nettle leaf beetle (Chrysolina fastuosa ) 5-6mm This leaf beetle is found on hemp nettle and dead nettle plants. It is beautifully coloured with its typically metallic green base and blue, red and gold banding. The elytra are densely punctured. Where to look - Found mainly in wetlands from March to December from the Central Belt to Aberdeenshire and Inverness © Ben Hamers © Ben Rosemary leaf beetle (Chrysolina americana ) 6-8mm The Rosemary beetle is a recent invasive non- native species introduced to the UK through the international plant trade. This beetle is metallic red/burgundy with green striping. There are lines of punctures typically following the green stripes. Where to look - Found in nurseries, gardens and parks. Feeds on lavender and rosemary in particular. There have been records in Edinburgh but this beetle is spreading. -

Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) in Cyprus - a Study Initiated from Social Media

Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e61349 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.9.e61349 Research Article First records of the pest leaf beetle Chrysolina (Chrysolinopsis) americana (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) in Cyprus - a study initiated from social media Michael Hadjiconstantis‡, Christos Zoumides§ ‡ Association for the Protection of Natural Heritage and Biodiversity of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus § Energy, Environment & Water Research Center, The Cyprus Institute, Nicosia, Cyprus Corresponding author: Michael Hadjiconstantis ([email protected]) Academic editor: Marianna Simões Received: 24 Nov 2020 | Accepted: 22 Jan 2021 | Published: 12 Feb 2021 Citation: Hadjiconstantis M, Zoumides C (2021) First records of the pest leaf beetle Chrysolina (Chrysolinopsis) americana (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) in Cyprus - a study initiated from social media. Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e61349. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.9.e61349 Abstract The leaf beetle Chrysolina (Chrysolinopsis) americana (Linnaeus, 1758), commonly known as the Rosemary beetle, is native to some parts of the Mediterranean region. In the last few decades, it has expanded its distribution to new regions in the North and Eastern Mediterranean basin. Chrysolina americana feeds on plants of the Lamiaceae family, such as Rosmarinus officinalis, Lavandula spp., Salvia spp., Thymus spp. and others. Chrysolina americana is considered a pest, as many of its host plants are of commercial importance and are often used as ornamentals in house gardens and green public spaces. In this work, we report the first occurrence of C. americana in Cyprus and we present its establishment, expansion and distribution across the Island, through recordings for the period 2015 – 2020. The study was initiated from a post on a Facebook group, where the species was noticed in Cyprus for the first time, indicating that social media and citizen science can be particularly helpful in biodiversity research. -

PRA Chrysolina Americana

CSL Pest Risk Analysis for Chrysolina americana CSL copyright, 2005 Pest Risk Analysis For Chrysolina americana STAGE 1: PRA INITIATION 1. What is the name of the pest? Chrysolina americana L. Coleoptera Chrysomelidae - Rosemary beetle synonym = Chrysomela americana Taeniochrysa americana 2. What is the reason for the PRA? This PRA was initiated after live specimens were found south London in May 2000. The PRA was completed on 31st May 2000. April 2002 update: A paper summarising previous findings and the distribution of this organism in London and the south-east of England concluded that it is now established in England (Salisbury, 2002). Information from Salisbury (2002) has been used to update the PRA of May 2000. Such information is shown as “April 2002 update”. 3. What is the PRA area? This PRA considers the UK as the PRA area. STAGE 2: PEST RISK ASSESSMENT 4. Does the pest occur in the PRA area or does it arrive regularly as a natural migrant? As at 31st May 2000: No. This beetle does not occur or arrive regularly as a natural migrant. It is native to southern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa (Balachowsky, 1963). April 2002 update: Yes, Chrysolina americana has established in the UK. Salisbury (2002) provides a distribution map of this pest in England. Most records are from the south-east of England, but there are also records from the Norwich area and south Yorkshire. 5. Is there any other reason to suspect that the pest is already established in the PRA area? As at 31st May 2000: No. -

High Risk Plants – RHS Shows

High Risk Plants – RHS Shows Last Revision: March 2019 Executive Summary New pests and diseases of plants (collectively referred to as pests) are introduced to the UK every year. Import and movement of plants for planting is a major pathway for the introduction and spread of these pests. In order to combat this, there are official regulations on movement of plants which depend on their species and origin. This document is intended to provide guidance to both exhibitors at RHS shows and to shows staff on plant health regulations and RHS plant health policy. It is intended to provide guidance on plants that represent a significant risk to UK plant health because of the pests that may be associated with them. Although it will be updated as new information becomes available it cannot provide an exhaustive list of all risks. The document does not provide guidance on plants that are pests in their own right due to their invasiveness, and whose movement is regulated by legislation, e.g. plants listed in Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) or in Commission Implementing Regulation 2017/1263. A list of plants on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife & Countryside Act (1981) is available here, and those controlled by Commission Implementing Regulation 2017/1263 are detailed here. This document provides guidance on import regulations but is NOT an exhaustive list of all requirements on imported plants. Plant health regulations are updated regularly. If you are sourcing plants from abroad for RHS shows, you should always check the latest plant health requirements with the APHA. -

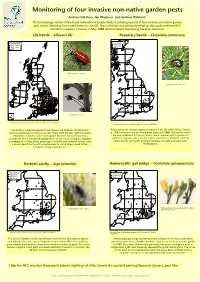

Monitoring of Four Invasive Non-Native Garden Pests

Monitoring of four invasive non-native garden pests Andrew Salisbury, Ian Waghorn and Andrew Halstead The Entomology section of the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) is collating records of four invasive non-native garden pest insects following their establishment in the UK. Data collection has previously relied on data gathered from RHS members’ enquiries, however in May 2008 internet- based monitoring has been launched. Lily beetle – Lilioceris lilii Rosemary beetle – Chrysolina americana First reported Firs t rec orded 1994-1999 1939-1989 2000-2004 1990-1999 2005- 2000+ Adult lily beetle (Photo R. Key) Rosemary beetle adult (RHS) Lily beetle larvae (RHS) Distribution of the Lily beetle in Britain and Ireland (December 2007). Produced using DMAP© Distribution of Rosemary beetle in Britain. (January 2008). Produced using DMAP© Lily beetle is a defoliating pest of lilies (Lilium) and fritillaries (Fritillaria) that Rosemary beetle was first reported outdoors in the UK at RHS Wisley Garden became established in Surrey in the late 1930s. Until the late 1980s the beetle in 1994, however it was not found there again until 2000. During that time it remained confined to south east England. However during the past two became established in London, and is now a common pest in gardens in decades the beetle has spread rapidly and it is now found throughout England, south east England, with scattered reports from the rest of Britain. Both the is widespread in Wales and is spreading in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Little adults and the grey grubs defoliate rosemary, lavender and some other is known about the threat this beetle poses to native Snake’s head fritillary related plants. -

Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the Guts of Insects Feeding on Plants: Prospects for Discovering Plant-Derived Antibiotics Katarzyna Ignasiak and Anthony Maxwell*

Ignasiak and Maxwell BMC Microbiology (2017) 17:223 DOI 10.1186/s12866-017-1133-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the guts of insects feeding on plants: prospects for discovering plant-derived antibiotics Katarzyna Ignasiak and Anthony Maxwell* Abstract Background: Although plants produce many secondary metabolites, currently none of these are commercial antibiotics. Insects feeding on specific plants can harbour bacterial strains resistant to known antibiotics suggesting that compounds in the plant have stimulated resistance development. We sought to determine whether the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in insect guts was a widespread phenomenon, and whether this could be used as a part of a strategy to identify antibacterial compounds from plants. Results: Six insect/plant pairs were selected and the insect gut bacteria were identified and assessed for antibiotic susceptibilities compared with type strains from culture collections. We found that the gut strains could be more or less susceptible to antibiotics than the type strains, or show no differences. Evidence of antibacterial activity was found in the plant extracts from five of the six plants, and, in one case Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar Periwinkle), compounds with antibacterial activity were identified. Conclusion: Bacterial strains isolated from insect guts show a range of susceptibilities to antibiotics suggesting a complex interplay between species in the insect gut microbiome. Extracts from selected plants can show antibacterial activity but it is not easy to isolate and identify the active components. We found that vindoline, present in Madagascar Periwinkle extracts, possessed moderate antibacterial activity. We suggest that plant-derived antibiotics are a realistic possibility given the advances in genomic and metabolomic methodologies. -

Swiss Herbal Note 7

Pflanzen Agroscope Transfer | Nr. 227/ 2018 Swiss Herbal Note 7 Rückblick auf 2017 in der Schweiz gemeldete Schädlinge auf Heil- und Gewürzpflanzen Juni 2018 Inhaltsverzeichnis Ziel 1 Longitarsus lycopi, L. ferrugineus. (Altise des menthes) 2 Rosmarinkäfer (Chrysolina americana) 6 Raupe auf Basilikum (Acronicta rumicis?) 8 Nachtschnecken (Weg-,Ackerschnecken) (Deroceras laeve ou Deroceras sp.) auf Stevia 9 Gartenlaubkäfer (Phyllopertha horticola). Bekämpfungsversuch auf Edelweiss 11 Dickmaulrüssler (Otiorhyncus sp.). Bekämpfungsversuch auf Alpenlein 13 Eine Wildbiene besucht Purpur-Sonnenhut (Echinacea purpurea) Autoren: Ziel Claude-Alain Carron Catherine Baroffio Bereitstellung von Informationen zu Schädlingen, die 2017 in der Estelle Schneider Schweiz Schäden bei Heil- und Gewürzpflanzen verursacht haben und das Aufzeigen von Strategien zu ihrer biologischen Bekämpfung. Swiss Herbal Note 7 Longitarsus lycopi, L. ferrugineus Kultur: Hauptkultur Pfefferminze (Mentha × piperita) Nebenkulturen: Mentha, Melissa, Thymus, Salvia, Hyssopus, Lippia,… Beobachtungen: Longitarsus stellte 2017 für die Minzenproduzenten das grösste Schädlingsproblem dar. In Ayent mussten 5000 m2 einer Kultur im 3. Standjahr wegen des zu starken Befalls nach der ersten Ernte zerstört werden. In Contoz/Sembrancher und in Bruson meldeten zwei andere Produzenten dieselben Probleme. Die Minzenkulturen wuchsen nach der ersten Ernte sehr schlecht nach, der Wiederaufwuchs war langsam und unregelmässig, 100% der Blätter waren von Longitarsus durchlöchert. Arbeiten 2017: Basierend -

Literature on the Chrysomelidae from CHRYSOMELA Newsletter, Numbers 1-41 October 1979 Through April 2001 May 18, 2001 (Rev

Literature on the Chrysomelidae From CHRYSOMELA Newsletter, numbers 1-41 October 1979 through April 2001 May 18, 2001 (rev. 1)—(2,635 citations) Terry N. Seeno, Editor The following citations appeared in the CHRYSOMELA process and rechecked for accuracy, the list undoubtedly newsletter beginning with the first issue published in 1979. contains errors. Revisions and additions are planned and will be numbered sequentially. Because the literature on leaf beetles is so expansive, these citations focus mainly on biosystematic references. They Adobe Acrobat® 4.0 was used to distill the list into a PDF were taken directly from the publication, reprint, or file, which is searchable using standard search procedures. author’s notes and not copied from other bibliographies. If you want to add to the literature in this bibliography, Even though great care was taken during the data entering please contact me. All contributors will be acknowledged. Abdullah, M. and A. Abdullah. 1968. Phyllobrotica decorata de Gratiana spadicea (Klug, 1829) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, DuPortei, a new sub-species of the Galerucinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomel- Cassidinae) em condições de laboratório. Rev. Bras. Entomol. idae) with a review of the species of Phyllobrotica in the Lyman 30(1):105-113, 7 figs., 2 tabs. Museum Collection. Entomol. Mon. Mag. 104(1244-1246):4-9, 32 figs. Alegre, C. and E. Petitpierre. 1982. Chromosomal findings on eight Abdullah, M. and A. Abdullah. 1969. Abnormal elytra, wings and species of European Cryptocephalus. Experientia 38:774-775, 11 figs. other structures in a female Trirhabda virgata (Chrysomelidae) with a summary of similar teratological observations in the Coleoptera. -

Shropshire Entomology Issue 1.Pdf

Shropshire Entomology – April 2010 (No.1) A bi-annual newsletter focussing upon the study of insects and other invertebrates in the county of Shropshire (V.C. 40) April 2010 (Vol. 1) Editor: Pete Boardman [email protected] ~ Welcome ~ I think these are indeed exciting times to be involved in entomology in Shropshire! We are building an impetus on the back of the first annual Shropshire Entomology Day held in February at Preston Montford Field Centre (a review of which will be published in the Shropshire Invertebrates Group (SIG) end of year review), and with the establishment of the Shropshire Environmental Data Network (SEDN) invertebrate database enabling an assessment of many species distributions for the first time in the county. On the back of these developments a number of people felt it might be a good idea to offer the opportunity to entomologists and naturalists to come together and detail notes and articles of interest relating to entomology in Shropshire. We are aiming to produce two newsletters circulated electronically through our local and regional networks each year in April and then in October. We hope that the style is informative and relaxed but accurate and enlightening . If you would like to continue to receive Shropshire Entomology or would like to contribute to future newsletters please contact me at the above email address. The deadline for submission for the second newsletter is Friday September 10th 2010 with a publication target of the beginning of October. A very big thank you to everyone who has contributed to this newsletter!! Please feel free to pass this on to anyone who you think might enjoy reading it. -

Contribution to the Knowledge of Sawfly Fauna (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) of the Low Tatras National Park in Central Slovakia Ladislav Roller - Karel Beneš - Stephan M

NATURAE TUTELA 10 57-72 UITOVSKY MIM li AS 'nix, CONTRIBUTION TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF SAWFLY FAUNA (HYMENOPTERA, SYMPHYTA) OF THE LOW TATRAS NATIONAL PARK IN CENTRAL SLOVAKIA LADISLAV ROLLER - KAREL BENEŠ - STEPHAN M. BLANK JAROSLAV HOLUŠA - EWALD JANSEN - M ALTE JÄNICKE- SIGBERT KALUZA - ALEXANDRA KEHL - INGA KEHR - MANFRED KRAUS - ANDREW D. LISTON - TOMMI NYMAN - HAIYAN NIE - HENRI SAVINA - ANDREAS TAEGER - MEICAI WEI L. Roller, K. Beneš, S. M. Blank, J. Iloluša, E. Jansen, M. Jänicke, S. Kaluza, A. Kehl, 1. Kehr, M. Kraus, A. D. Liston,T. Nyman, II. Nie, II. Savina, A. Taeger, M. Wei: Príspevok k poznaniu fauny hrubopásych (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) Národného parku Nízke Tatry Abstrakt: Počas deviateho medzinárodného pracovného stretnutia špecialistov na hrubopáse blanokrídlovce (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) v júni 2005 bol vykonaný ľaunistický prieskum hrubopásych na viacerých lokalitách Národného parku Nízke Tatry. Celkovo bolo zaznamenaných 200 druhov a osem čeľadí hrubopásych. Ďalších dvanásť taxónov nebolo identifikovaných do druhu. Dolerus altivolus, D. hibernicus, Eriocampa dorpatica, Euura hastatae, Fenella monilicornis, Nematus yokohamensis tavastiensis, Pachynematus clibrichellus. Phyllocolpa excavata, P. polita, P. ralieri, Pontania gallarum, P. virilis, Pristiphora breadalbanensis, P. coactula a Tenthredo ignobilis boli zistené na Slovensku po prvýkrát. Významný počet ľaunistický zaujímavých nálezov naznačuje vysokú zachovalosť študovaných prírodných stanovíšť v širšom okolí Demänovskej a Jánskej doliny, Svarína a v národnej prírodnej rezervácii Turková. Kľúčové slová: Hymenoptera, Symphyta, Národný park Nízke Tatry, ľaunistický výskum INTRODUCTION Sawflies are the primitive phytophagous hymenopterans (suborder Symphyta), represented in Europe by 1366 species (LISTON, 1995; TAEGER & BLANK, 2004; TAEGER et al., 2006). In Slovakia, about 650 species belonging to 13 families of the Symphyta should occur (ROLLER, 1999).