Competition Policy and the British Bus Industry: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground

£5 when sold in paper format Available free by email upon application to: [email protected] An auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground Collectables Enamel signs & plates, maps, posters, badges, destination blinds, timetables, tickets & other relics th Saturday 25 February 2017 at 11.00 am (viewing from 9am) to be held at THE CROYDON PARK HOTEL (Windsor Suite) 7 Altyre Road, Croydon CR9 5AA (close to East Croydon rail and tram station) Live bidding online at www.the-saleroom.com (additional fee applies) TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Transport Auctions of London Ltd is hereinafter referred to as the Auctioneer and includes any person acting upon the Auctioneer's authority. 1. General Conditions of Sale a. All persons on the premises of, or at a venue hired or borrowed by, the Auctioneer are there at their own risk. b. Such persons shall have no claim against the Auctioneer in respect of any accident, injury or damage howsoever caused nor in respect of cancellation or postponement of the sale. c. The Auctioneer reserves the right of admission which will be by registration at the front desk. d. For security reasons, bags are not allowed in the viewing area and must be left at the front desk or cloakroom. e. Persons handling lots do so at their own risk and shall make good all loss or damage howsoever sustained, such estimate of cost to be assessed by the Auctioneer whose decision shall be final. 2. Catalogue a. The Auctioneer acts as agent only and shall not be responsible for any default on the part of a vendor or buyer. -

OFFICIAL TIMETABLE and MAP of BUS ROUTES - Summer Service, (First Issue)50 23/5/28''

LotNo Description Hammer 1 1928 East Surrey Traction Co Ltd ''OFFICIAL TIMETABLE AND MAP OF BUS ROUTES - Summer Service, (First Issue)50 23/5/28''. In good unmarked condition with some light wear and creasing to covers. [1] 2 London Transport fleetnumber BONNET PLATE and Registration NUMBER PLATE from AEC Regent RT 2906 (MLL80 653). The original bus with this number entered service at Alperton garage in 1952 and the final RT 2906 was withdrawn at Seven Kings garage in 1974, being scrapped the same year. Both plates are in ex-vehicle condition.[2] 3 London Underground ENAMEL ROUNDEL SIGN from King's Cross St Pancras Station. This is a medium-size sign950 measuring 51'' (131cm) across by 42'' (107cm) high, estimated to date from the 1980s/90s, and comes complete with brass frame. It has been mounted on board for display purposes. In excellent condition. [1] 4 Set of Green Line Coach leaflets bearing names of former independent companies comprising Route AW dated25 26-4-32 and 1-6-32 (both Bucks Expresses (Watford) Ltd), Route BG dated 5-8-32 (Skylark Motor Coach Co Ltd) and Route CF dated 24-8-32 (Regent Coach Service). All lightly used, the last has some stains. [4] 5 1930s LGOC/LPTB PANEL TIMETABLES comprising routes 79/115/620 (25-3-32), 494/194 (30.12.30), 113 (28.2.34),40 418/70B & 70D (25.4.34) and 81 (17-2-37). All with some wear/damage to varying degrees. [5] 6 London Transport 'Gibson' TICKET MACHINE no. 21391, a letter codes machine which appears to be in working250 order and prints a good ticket with 'London Transport' still on the plate. -

Combining Scheduled Commuter Services with Private Hire, Sightseeing and Tour Work: the London Experience by Derek Kenneth Robbins and Peter Royden White*

CEE INGS Twenty-sixth Annual Meeting Theme: "Markets and Management in an Era of Deregulation" November 13-15, 1985 Amelia Island Plantation Jacksonville, Florida Volume XXVI Number 1 1985 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH FORUM In conjunction with CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION 4 RESEARCH FORM 273 Combining Scheduled Commuter Services with Private Hire, Sightseeing and Tour Work: The London Experience By Derek Kenneth Robbins and Peter Royden White* ABSTRACT dent operators ran only 8% of stage carriage mileage but operated 91% of private hire and contract The Transport Act 1980 completely removed mileage and 86% of all excursions and tours quantity control for scheduled express services mileage.' The 1980 Transport Act removed the which carry passengers more than 30 miles meas- quantity controls for two of the types of operation, ured in a straight line. It also made road service namely scheduled express services and most excur- licenses easier to obtain for operators wishing to run sions and tours. However the quality controls were services over shorter distances by limiting the scope retained, in the case of vehicle maintenance and for objections. As a result of these legislative inspections being strengthened. The Act redefined changes a new type of service has emerged over the "scheduled express" services. Since 1930 they had last four years carrying long-distance commuters to been defined by the minimum fare charged and and from work in London. Vehicles used on such because of inflation many short distance services services would only be utilised for short periods came to be defined as "Express", despite raising the every weekday unless other work were also found minimum fare yardstick in both 1971 and 1976. -

Notices and Proceedings

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2158 PUBLICATION DATE: 20 September 2013 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 11 October 2013 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 04/10/2013 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk Copies of Notices and Proceedings can be inspected free of charge at the Office of the Traffic Commissioner in Leeds. -

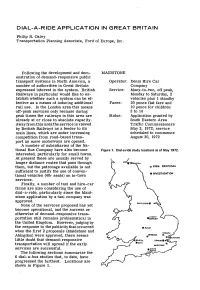

Dial-A-Ride Application in Great Britain

DIAL-A-RIDE APPLICATION IN GREAT BRITAIN Philip R. Oxley Transportation Planning Associate, Ford of Europe, Inc. Following the development and dem- MAIDSTONE onstration of demand-responsive public transport systems in North America, a Operator: Denis Hire Car number of authorities in Great Britain Company expressed interest in the system. British Service: Many-to-two, off peak, Railways in particular would like to es- Monday to Saturday, 2 tablish whether such a system can be ef- vehicles plus 1 standby fective as a means of inducing additional Fares: 20 pence flat fare and rail use. In the London area this means 10 pence for children off-peak services only because during 3 to 14 peak times the railways in this area are Status: Application granted by already at or close to absolute capacity. South Eastern Area Away from this areathe service is viewed Traffic Commissioners by British Railways as a feeder to its May 3, 1972; service main lines, which are under increasing scheduled to commence competition from road-based trans- August 30, 1972 port as more motorways are opened. A number of subsidiaries of the Na- tional Bus Company have also become Figure 1. Dial-a-ride study locations as of May 1972. interested, particularly for small towns. At present these are usually served by longer distance routes that pass through them, but the patronage available is not sufficient to justify the use of conven- S INVESTIGATIONPROPOSAL tional vehicles (40+ seats) on in-town services. Finally, a number of taxi and hire-car firms are also considering the use of dial-a-ride, particularly since the Maid- stone application by a taxi company was approved. -

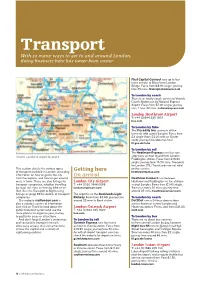

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Rules of the Library of the P.S.V. Circle

RULES OF THE LIBRARY OF THE P.S.V. CIRCLE Information The P.S.V. Circle Library has available for loan P.S.V. Circle publications which are no longer on sale. Such publications include old news sheets, fleet histories, fleet listings and also some Ian Allan publications. A deposit of £10 will be required from any member who wishes to borrow publication(s). This is refundable when publications are returned in good condition, subject to the rules below. The deposit may be retained by the Circle to cover anticipated future loans. RULES 1) Any member of the P.S.V. Circle may use the library provided that his membership subscription is not in arrear and that he has not been excluded by operation of rule 9. 2) The total number of publications which may be borrowed at any one time is four. 3) Members must quote their Circle membership number in all correspondence. 4) A deposit of £10 will be required. This sum may be forwarded by cheque or postal order payable to 'The P.S.V. Circle'. The deposit shall be £10 irrespective of the number of publications borrowed at any one time. 5) All borrowed publications shall be returned to the issuing librarian no later than one month of despatch to the member at the time of borrowing. 6) The library stock is kept by the Librarian and several Assistant Librarians. Requests may be made to borrow from multiple librarians. The initial request must be made to the Circle Librarian. 7) Members shall not mark Library stock in any way and shall be held responsible for returning publications to the Issuing Librarian in the same condition as received by them. -

Office of the Traffic Commissioners (West of England)

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WEST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2523 PUBLICATION DATE: 17 February 2015 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 10 March 2015 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (W est of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 03/03/2015 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e -mail. To use this service please send an e- mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage -commercial -vehicle -operator -licence -onl ine NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All post relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (W est of England) Jubilee House Croydon Street Bristol BS5 0DA The public counter at the Bristol office is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. -

See Our Midland Red Feature in Buses Magazine

IDENTITY PARADE Once the biggest bus company in the country, Midland Red projected a simple and highly effective brand image. Thirty-five years after this instantly recognisable operator was broken up, The MHD Partnership offers its bold suggestion of how it could have been branded today had events taken a different turn. TAKE IT AS RED idland Red — the applied its corporate poppy red from 1972 the existing name Birmingham & Midland and the following year the heart was ripped “Midland Red” has Motor Omnibus Company out of the business when most routes in become a shorter, M to give it its original name Birmingham and the Black Country were sold snappier and more — branded itself as ‘The Friendly Midland to West Midlands PTE. In 1981, NBC split the modern “red” with Red’ and was one of the great names of the remaining bus operations into four separate the new, improved regulated bus industry. companies, with further new subsidiaries taking identity following It grew rapidly to become the biggest on the coaches and central engineering works; suit. Created territorial bus company of all, stretching out today those remnants are run mainly by Arriva, using a bespoke, from Birmingham with a complex network First, Stagecoach and Rotala-owned Diamond. hand-drawn logo, of urban, interurban and rural routes across But suppose things had taken a different the lower case Warwickshire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, turn in 1973 and Midland Red survived wording is easy Shropshire, Staffordshire and Leicestershire. today. How might its buses be branded? That on the eye and It was part of the BET group until the was this month’s brief to our creative friends has a flow that National Bus Company came along in 1969. -

Review of Firstgroup Bus Undertakings in Bristol Provisional Decision

Review of FirstGroup bus undertakings in Bristol Provisional decision 9 June 2017 © Crown copyright 2017 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Website: www.gov.uk/cma Members of the Competition and Markets Authority who are conducting this review Simon Polito (Chair of the Group) Anne Lambert Sarah Chambers Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority Andrea Coscelli (acting Chief Executive) The Competition and Markets Authority has excluded from this published version of the provisional decision report information which the CMA considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Contents Page Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Provisional decision .............................................................................................. 4 Provisional decision.................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction and background ............................................................................... -

Scotland/Northern Ireland

Please send your reports, observations, and comments by Mail to: The PSV Circle, Unit 1R, Leroy House, 9 436 Essex Road, LONDON, N1 3QP by FAX to: 0870 051 9442 by email to: [email protected] SCOTLAND & NORTHERN IRELAND NEWS SHEET 850-9-333 NOVEMBER 2010 SCOTLAND MAJOR OPERATORS ARRIVA SCOTLAND WEST Limited (SW) (Arriva) Liveries c9/10: 2003 Arriva - 1417 (P807 DBS), 1441 (P831 KES). Subsequent histories 329 (R129 GNW), 330 (R130 GNW), 342 (R112 GNW), 350 (S350 PGA), 352 (S352 PGA), 353 (S353 PGA): Stafford Bus Centre, Cotes Heath (Q) 7/10 ex Arriva Northumbria (ND) 2661/57/60/2/9/3. 899 (C449 BKM, later LUI 5603): Beaverbus, Wigston (LE) 8/10 ex McDonald, Wigston (LE). BLUEBIRD BUSES Limited (SN) (Stagecoach) Vehicles in from Highland Country (SN) 52238 9/10 52238 M538 RSO Vo B10M-62 YV31M2F16SA042188 Pn 9412VUM2800 C51F 12/94 from Orkney Coaches (SN) 52429 9/10 52429 YSU 882 Vo B10M-62 YV31MA61XVC060874 Pn 9?12VUP8654 C50FT 5/98 (ex NFL 881, R872 RST) from Highland Country (SN) 53113 10/10 53113 SV 09 EGK Vo B12B YV3R8M92X9A134325 Pn 0912.3TMR8374 C49FLT 7/09 Vehicles re-registered 52137 K567 GSA Vo B10M-60 YV31MGC1XPA030781 Pn 9212VCM0824 to FSU 331 10/10 (ex 127 ASV, K567 GSA) 52141 K571 DFS Vo B10M-60 YV31MGC10PA030739 Pn 9212VCM0809 to FSU 797 10/10 54046 SV 08 GXL Vo B12BT YV3R8M9218A128248 Pn 0815TAR7877 to 448 GWL 10/10 Vehicle modifications 9/10: fitted LED destination displays - 22254 (GSU 950, ex V254 ESX), 22272 (X272 MTS) 10/10: fitted LED destination displays - 22802 (V802 DFV).