Charles Dodgson, Adopted Member of the Macdonald Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unpublished Letters by George Macdonald

Defining Death as “More Life”: Unpublished Letters by George MacDonald Glenn Edward Sadler Who lives, he dies; who dies, he is alive. Phantastes ch. XIII ost readers of George MacDonald’s fiction, especially of his faerieM romances and fairytales, will recall his penetrating treatment of the subject of death and dying. A classic passage occurs, for example, at the conclusion of The Golden Key, when the Old Man of the Sea finally asks Mossy the ultimate question: [end of page 4] “You have tasted death now,” said the Old Man. “Is it good?” “It is good,” said Mossy. “It is better than life.” “No,” said the Old Man: “it is only more life.”1 Equally moving, in spite of its sentimentality, is the ending of At the Back of the North Wind, which depicts graphically Diamond’s dream-in- sleep death. Similarly, there is the ethereal death of the king, who becomes a sacrifice of “flaming red roses,” viewed by Curdie, at the end ofThe Princess and Curdie. As a writer of parables and fairytales, George MacDonald is at his best when he is seeing death through the eyes of a child. Through the eyes of his fictional children—Mossy, Diamond and Curdie—MacDonald envisions his cardinal belief in the cosmic role of the child, who as a redemptive figure participates in and exemplifies universal love and immortality. Mossy and Tangle become agents of life-giving renewal. Diamond is a source of lasting love. And Curdie is a symbol of universal victory over evil. In each case it is the process of dying-into-life (“more life”) that is MacDonald’s major concern: it is a theme which is to be found in everything he wrote. -

North Wind: a Journal of George Macdonald Studies

North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 39 Article 6 1-1-2020 A Personal Reflection on Colin Manlove and Stephen Prickett John Pennington Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Pennington, John (2020) "A Personal Reflection on Colin Manlove and Stephen Prickett," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 39 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol39/iss1/6 This In Memoriam is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Personal Reflection on Colin Manlove and Stephen Prickett John Pennington At the end of George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind, the narrator enters Diamond’s bedroom and sees the young boy seemingly asleep on his bed. The narrator states: “I saw at once how it was . I knew that he had gone to the back of the north wind” (298). With utter certitude, I’m sure that Colin and Stephen are also at the back of the north wind. My career as an academic in literature is indebted to Colin and Stephen, for they paved the way for serious academic study of George MacDonald, hardly a household name outside of the devoted readers of fantasy, fairy tales, and theology when I started my PhD program in the mid- 1980’s. -

Alice in Wonderland

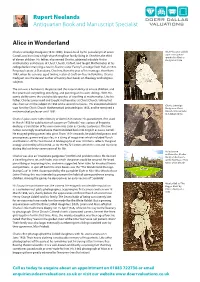

Rupert Neelands Antiquarian Book and Manuscript Specialist Alice in Wonderland Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), known to all by his pseudonym of Lewis Alice Pleasance Liddell, Carroll, was born into a high-church Anglican family living in Cheshire, the third aged seven, photo- graphed by Charles of eleven children. His father, also named Charles, obtained a double first in Dodgson in 1860 mathematics and classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and taught Mathematics at his college before marrying a cousin, Frances Jane “Fanny” Lutwidge from Hull, in 1827. Perpetual curate at Daresbury, Cheshire, from the year of his marriage, then from 1843, when his son was aged twelve, rector at Croft-on-Tees in Yorkshire, Charles Dodgson was the devout author of twenty-four books on theology and religious subjects. The son was a humourist. He possessed the natural ability to amuse children, and first practised storytelling, versifying, and punning on his own siblings. With this comic ability came the unshakeable gravitas of excelling at mathematics. Like his father, Charles junior read and taught mathematics at Christ Church, taking first class honours in the subject in 1854 and a second in classics. His exceptional talent Charles Lutwidge won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, and he remained a Dodgson at Christ mathematical professor until 1881. Church 1856-60 (John Rich Album, NPG) Charles’s jokes were rather literary or donnish in nature. His pseudonym, first used in March 1856 for publication of a poem on “Solitude”, was a piece of linguistic drollery, a translation of his own name into Latin as Carolus Ludovicus. -

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian David L. Neuhouser Mathematics Department Taylor University Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), better known as Lewis Carroll, is best known as the creative and imaginative author of the Alice stories, but he was also a mathematician at Christ Church College, Oxford University and a devout Christian. His mathematics, especially mathematical logic, contributed much to the charming “nonsense” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. However, his Christian thought is not evident in those books. In fact, they contain many parodies of morality poems for children. As a result of reading just these books, one might conclude that he was not even interested in morality. But to those who knew him personally, he seemed to be a rather pious, stodgy person. Also, he wrote essays and letters in defense of morality and Christianity as well as books and articles on mathematics. His writings on morality showed little of his literary imagination and his writings on mathematics give no indication of his Christianity. Only in Sylvie and Bruno and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded did Dodgson attempt to bring his literary creativity, mathematics, and Christianity all together in one artistic creation. This paper will attempt to answer the following questions. What motivated him to make this attempt and how successful was it? The Alice stories were the first really successful children’s stories which did not have obvious moral teachings. They were just for fun. However he wrote articles and letters against “indecent literature,” joking about sacred things, and immorality in plays. Some projects that he planned but never completed were: selections from the Bible to be memorized, selections from the Bible with pictures for children, and selections from Shakespeare with inappropriate content for young girls deleted. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

If Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll)

If Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) had not written Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he’d probably be remembered as a pioneer photographer. But his Oxford ‘day job’ was as Lecturer in Mathematics at Christ Church. What mathematics did he do? C L Dodgson Dodgson time-line 1832 Born in Daresbury, Cheshire 1843 Moves to Croft Rectory, Yorkshire ( ) 1844–49 At Richmond and Rugby Schools Lewis Carroll 1850 Matriculates at Oxford University 1851 Studies at Christ Church, Oxford 1852 Nominated a ‘Student’ at Christ Church Oxford 1854 Long Vacation at Whitby studying with ‘Bat’ Price First Class in Mathematics in his Finals Examinations mathematician 1856 Mathematical Lecturer at Christ Church Adopts the pseudonym Lewis Carroll “What I look like when I’m lecturing. The merest sketch, you will allow – Develops an interest in photography yet still I think there’s something grand 1860 Notes on the First Two Books of Euclid In the expression of the brow 1861 The Formulae of Plane Trigonometry and in the action of the hand.” 1862 Boat trip to Godstow with the C L Dodgson Liddell sisters 1865 The Dynamics of a Parti-cle Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 1866 ‘Condensation of Determinants’ read to the Royal Society 1867 An Elementary Treatise on Determinants 1868 The Fifth Book of Euclid 1871 Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There 1873 A Discussion of the Various Methods of Procedure in Conducting Elections 1876 The Hunting of the Snark 1879 Euclid and his Modern Rivals 1881 Resigns Mathematical Lecturership 1882 Euclid, Books I, II 1883 Lawn Tennis Tournaments 1884 The Principles of Parliamentary Representation 1885 A Tangled Tale 1886 The Game of Logic 1888 Curiosa Mathematica, I. -

Lewis Carroll, George Macdonald and Charles Dickens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository FANTASTICAL REFLECTIONS: LEWIS CARROLL, GEORGE MACDONALD AND CHARLES DICKENS By HAYLEY HANNAH FLYNN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines the presence and importance of the fantastical in literature of the Victorian period, a time most frequently associated with rationality. A variety of cultural sources, including popular entertainment, optical technology and the fairy tale, show the extent of the impact the fantastical has on the period and provides further insight into its origins. Lewis Carroll, George MacDonald and Charles Dickens, who each present very different style of writing, provide similar insight into the impact of the fantastical on literature of the period. By examining the similarities and influences that exist between these three authors and other cultural sources of the fantastical a clear pattern can be seen, demonstrating the origins and use of the fantastical in Victorian literature and providing a new stance from which it should be viewed. -

Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll’S and George Macdonald’S Nonsense Literature Adam Walker

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St. Norbert College North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies Volume 37 Article 2 1-1-2018 Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll’s and George MacDonald’s Nonsense Literature Adam Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind Recommended Citation Walker, Adam (2018) "Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll’s and George MacDonald’s Nonsense Literature," North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies: Vol. 37 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol37/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order: Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll's and George MacDonald's Nonsense Literature Adam Walker Introduction “Nonsense criticism, as it currently exists,” writes Josephine Gabelman in her new book A Theology of Nonsense (2016), “is essentially a secular enterprise. It is philosophical and psychoanalytical, philological and mathematical; it may be studied from a historical or cultural perspective, but apparently not a religious one” (162). Past scholarship has, in fact, not only avoided a serious consideration of theology regarding nonsense literature, but some scholars have gone so far as to insist that nonsense literature lacks any sense of the religious at all. -

Clarence Bicknell and George Macdonald: Figureheads of Society in Bordighera

Clarence Bicknell and George Macdonald: Figureheads of Society in Bordighera By Susie Bicknell February 2015 George MacDonald and Clarence Bicknell both settled in Bordighera in 1878. George was already an established literary personality with a large family and little money. Clarence was unknown with no particular vocation except as a priest, a bachelor (which he remained) and with enough private means to support himself. Within a few years, they had established themselves as pivots of society in Bordighera. However, it is strange not to know how much contact they had with each other, considering how much they had in common as stalwarts of Bordighera. They both had stints as priests. Reacting possibly to his Unitarian upbringing, Clarence, when he left Cambridge, favoured a return to a more Catholic orientated Anglican Church. Ordained in 1866, Clarence was a curate in a tough parish in Walworth, Surrey and then from 1873 spent six years on and off at Stoke on Tern with the rather mysterious “Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit” created by Roland Corbett which pursued High Church Anglo-Catholicism. But by the late 70s, the Brotherhood must have lost its allure for Clarence, and he travelled considerably, going as far afield as Morocco and possibly New Zealand. He ended up in Bordighera in 1878 invited by the Fanshawe family and became chaplain to the Anglican church there. Eighteen years older than Clarence, Scotsman George MacDonald also started with a religious calling. He left Aberdeen to study Congregationalism at Highbury Independent Theological College. After three years, he became pastor in 1850 at a Congregational Church in Arundel, Sussex. -

George Macdonald and E.T.A. Hoffmann

George MacDonald and E.T.A. Hoffmann Raphael Shaberman he influence of the German Romantic writers of the latter 18th and earlyT 19th centuries on the work of George MacDonald has long been acknowledged, not least by MacDonald himself. The most important of these was Novalis: George MacDonald’s first book was a small collection of translations from Novalis, an interest which MacDonald maintained until the end of his creative life. This reflected MacDonald’s mystical side. However, as to the construction of his fantasies and fairy tales, the influence of Hoffmann was considerable, and it is doubtful whether they would have taken the form they did had it not been for Hoffmann’s example. Though well-known in his own day—and not only in his native Germany—Hoffmann is today remembered for a handful of his tales, the inspirer of the ballets “Nutcracker” and “Coppelia,” and Offenbach’s opera “Tales of Hoffmann.” Thus he remains largely unread, as to his greater output, and unrecognised for the pioneer he was. Indeed he is often mistaken for Heinrich Hoffmann, author of the notorious “Struwwelpeter,” or even for Professor Hoffmann, the conjurer. His achievements in music were many-sided; he was one of the earliest and finest of music critics, he influenced Schumann, who named one of his suites for piano “Kreisleriana” (“Johannes Kreisler” was a pseudonym of Hoffmann). He was also a conductor, teacher, composer, producer of opera, designer and painter of scenery, etc. His opera “Undine” is a nice link with MacDonald, for the story on which it was based was the latter’s favourite fairy tale: the author, Fonqué, was known to Hoffmann. -

In.T-Ro"D :U'g Ti-O N

.IN.T-RO "D :U'G TI-O N "No! No! The-a'd ventures-, first," sajd'tlie Gryphon in .an impatient: tone: ."ex- planations, take'such a dreadful time.":('The'L6bster-Quadrille')'". •-. -. ' "Even a joke should Have some meaning- -and a child's'more important than a'joke, I hope." {'Queen Alice'}1 .. i: Tlie Child, Nonsense and Meaning '"The'adventures'..first'".,\says Carroll's' Gryphon; \vitli,his^dread of 'explanations', arid. aU1. readers: know;, this-is'.the'right orderuYet rritro^' duction's'incvitably "come before,adventures.and'intrbdu'crions.tend .to mean explanations:-Lbts of-things'happen:the.^\Tong.,way .rouh'd in' these .texts -?;1"Sentence-first —^"erdic^afterivards'i'i'-sliouts the. Queen of Hearts3'—.so:readerS'vWho'.share: the.Gryplion's:priorities^ can al\vays: read the introduction-after th'e:stories,"or:not at;all/You simplytfollow the instructions of.the King of.Hearts: "'Begin-at'the-bcgirining'..'-. ..and go on;tilTy6urcbme.io the-endr.then stop'".3. ••LJ-.: ..._ ..; ; .• . .;-.:i. : Yet,Cafrolls:herd)iie,'atLthc hearfbf,tHese:adventuresj :s, very.much concerned with'.'questions-of 'mean ing:: iVheii sKe 'dreamily: finds her way tb'the other side of.the looking-glass, one~:of the;first things she encounters "Is a. poem:'call ed:'Jabben,vocky.>.':After.-.reading ."it, '.Alice remarks '"It seems very/pretty.1.-/.'-but it's-rather hard to ^understand!'." '"Somehowit-'fills-my:head:.\vith;ideas''',^he reflects; '"only 1''don't exactly 'la'iow what they>are!".!1 " : ..•L-jiurT't ,- -.'- . ..iL:-. .••-.. -/'v,.- In this-Tespectfthe'nonsensical.mirrbr-poem;'Jabber\vock;'>.stands'asv a.mirror:of the classic literary,double-act.o£whicKJt is.'part: All readers- Q{ Alice's Adventures.in'.Wondcrlimd 'and~Tliroiigh''the--Lookwg-'Clas$, those.