Cultural Identity, Racialization, and Being Cuban in the Bronx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITA September 2019

CLARENCE LUSANE, PH.D. CURRICULUM VITA September 2019 254 Madison Street, NW Washington, DC 20011 (202) 806-9383 office (202) 641-0791 cell [email protected] or [email protected] CAREER ACCOMPLISHMENTS • Former Chair, Department of Political Science – Howard University (2015-2019) • Tenured Full Professor • Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Relations – American University (1997-2015) • Political Researcher and Writer • Public Policy Consultant • Former Commissioner – District of Columbia Commission on African American Affairs SUMMARY OF ACHIEVEMENTS AND SKILLS • Author of eight books and contributor to 20 books • Published more than 100 journal, magazine, and news articles • Professional consultant to the U.S. Department of State, Congressional Black Caucus, Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, World Council of Churches and other U.S. government, private and non-profit organizations and agencies • Recipient of prestigious British Council Atlantic Fellowship in Public Policy • Lecturer on international affairs, global racism, electoral politics, and other issues at over 40 colleges and universities including Yale, Harvard, Howard, Columbia, Georgetown, University of Chicago, and University of California-Berkeley • Lectured in over 60 countries including Bosnia-Herzegovina, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Cuba, England, France, Guadeloupe, Hungary, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Rwanda, Scotland, South Africa, South Korea, and Ukraine • Broad international, national, and local organizing experience with political organizations and community-based Non-Governmental Organizations • International election observer in Haiti and Democratic Republic of the Congo WORK/EMPLOYMENT Howard University, Department of Political Science, Washington, DC. July 2019 to present: Professor Teach undergraduate and graduate courses in the areas of Black Politics, Comparative Politics, and International Relations. -

The Mortara Center for International Studies Walsh School of Foreign Service Georgetown University Annual Report 2017 - 2018 About the Center

The Mortara Center for International Studies Walsh School of Foreign Service Georgetown University Annual Report 2017 - 2018 About the Center Officially opened in January 2003, the Mortara Center for International Studies was founded through the generosity of the late Mr. Michael P. Mortara, his wife, Mrs. Virginia Mortara, and friends and colleagues. The Mortara family envisioned a center of scholarly inquiry at the School of Foreign Service that would embody the mission of the School and its focus on the intersection of theory and practice in international affairs. Mission Statement The Mortara Center for International Studies seeks to advance schlarship and inform policy by combining the expertise of scholars and experience of international affairs practitioners to illuminate the fundamental forces - political, economic and cultural - that shape international relations. To realize this mission, the Center: • organizes and cosponsors lectures, workshops and conferences • provides support for research and publications • generates communities of research 1 LetterLetter fromfrom thethe DirectorDirector Dear Friends of the Mortara Center, Over the past year, the Mortara Center has con- tinued to promote and energize faculty and student research at the School of Foreign Service. Focusing on pressing global problems from climate change to financial crisis to mitigating violence in post-conflict states, the Center has hosted hundreds of events, con- vened working groups, and supported deep student mentorship experiences through the Mortara Under- graduate Research Fellowship program. For the 2017-2018 annual report, I would like to draw your attention to two exceptional programs, which exemplify the extraordinary work happening at Mortara and the School. The Center was honored to host the launch of the Mortara Distinguished Professor of Diplomacy Madeleine Albright’s book Fascism: A Warning. -

Volume 19.1 National Political Science Review Caribbeanization of Black Politics May 16 2018

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 Yvette Clarke U.S. Representative (D.-MA) CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Associate Managing Editor Julia Jordan-Zachery Providence College Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon D. Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Augusta University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, St. Louis Niambi Carter—Howard University Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Marion Brown—Brown University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Nyron Crawford—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Heath Fogg-Davis—Temple University H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Christina Rivers—DePaul University Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Neil Roberts—Williams College Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Fatemeh Shafiei—Spelman College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

Institutional Decolonization: Toward a Comprehensive Black Politics

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 20.1 INSTITUTIONAL DECOLONIZATION: TOWARD A COMPREHENSIVE BLACK POLITICS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 20.1 INSTITUTIONAL DECOLONIZATION: TOWARD A COMPREHENSIVE BLACK POLITICS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS National Political Science Review | ii THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon D. Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Oklahoma State University EDITORIAL RESEARCH ASSISTANTS Lisa Beard Armand Demirchyan LaShonda Carter Amber Gordon Ashley Daniels Deshanda Edwards EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, Niambi Carter—Howard University St. Louis Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Marion Orr—Brown University Nyron Crawford—Temple University Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Heath Fogg Davis—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Christina Rivers—DePaul University Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Neil Roberts—Williams College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

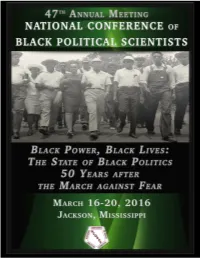

NCOBPS 2016 Program

1 2 Dear Conference Attendees and Supporters: On behalf of the leadership of the National Conference of Black Political Scientists (NCOBPS), I welcome you to the 47th Annual Meeting of this beloved association. For nearly 50 years, NCOBPS has been an intellectual home and a vibrant forum for Black political scientists and other scholars who have seen it as our mission to use various forms of political and policy analysis so to enlighten, empower, and to serve Global Black communities. True to the vision of our founders and elders, our mission remains that of a ‘growing organization in the struggle for the liberation of African peoples.’ This mission is no less relevant today than it was nearly 50 years ago given that Global Black communities still confront an unnerving number of barriers to racial, political, and economic justice as intersected by other forms of oppression. The theme of this 47th Annual Meeting is “Black Power, Black Lives: 50 Years After the March Against Fear.” It pays tribute to a heroic activism, rooted in Mississippi soil, which countered white supremacy and demanded the full recognition of African Americans’ humanity and citizenship rights. This local struggle also continues. While you are here in Jackson, Mississippi, one of the activist headquarters and continuing battlefields for human rights equality, enjoy yourself (eat some catfish, listen to some blues music, and see the sights) but of course take full advantage of all of what our brilliant conference organizers and local arrangements committee have provided. We extend our great thanks for their extreme dedication and hard work! We also extend a warm greeting to all of our guests and a heart-felt thanks to all of our co-sponsors and local partners. -

Caribbeanization of Black Politics Sharon D

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 Yvette Clarke U.S. Representative (D.-MA) CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Associate Managing Editor Julia Jordan-Zachery Providence College Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Augusta University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, St. Louis Niambi Carter—Howard University Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Marion Brown—Brown University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Nyron Crawford—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Heath Fogg-Davis—Temple University H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Christina Rivers—DePaul University Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Neil Roberts—Williams College Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Fatemeh Shafiei—Spelman College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" Was a "War on Blacks" Kenneth B

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2002 Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" Was a "War on Blacks" Kenneth B. Nunn University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth B. Nunn, Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" Was a "War on Blacks," 6 J. Gender Race & Just. 381 (2002), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/107 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" was a "War on Blacks" Kenneth B. Nunn* INTRODUCTION The War on Drugs I has had a devastating effect on African American communities nationwide. Throughout the drug war, African Americans have been disproportionately investigated, detained, searched, arrested and charged with the use, possession and sale of illegal drugs.2 Vast numbers of African Americans have been jailed and imprisoned pursuant to the nation's tough drug trafficking laws, implemented as part of the War on Drugs.3 Indeed, in some * Professor of Law, University of Florida, Levin College of Law. -

(In)Visible Black Europe: Race, Rights & Politics

THE STATE OF (IN)VISIBLE BLACK EUROPE: RACE, RIGHTS & POLITICS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 29, 2008 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 110–2–10] ( Available via http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63–749 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:41 Dec 19, 2012 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\WORK\042908.TXT KATIE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida, BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland, Chairman Co-Chairman LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin New York CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut MIKE McINTYRE, North Carolina HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York HILDA L. SOLIS, California JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts G.K. BUTTERFIELD, North Carolina SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GORDON SMITH, Oregon ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MIKE PENCE, Indiana EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS David J. Kramer, Department of State VACANT, Department of Defense David Bohigian, Department of Commerce (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:41 Dec 19, 2012 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\WORK\042908.TXT KATIE THE STATE OF (IN)VISIBLE BLACK EUROPE: RACE, RIGHTS & POLITICS APRIL 29, 2008 COMMISSIONERS Page Hon. -

'Hitler's Black Victims: the Historical Experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi Era'

H-German Lennox on Lusane, 'Hitler's Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi Era' Review published on Monday, November 1, 2004 Clarence Lusane. Hitler's Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi Era. New York and London: Routledge, 2003. 320 pp. $100.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-415-93121-2; $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-415-93295-0. Reviewed by Sara Lennox (Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Massachusetts, Amherst) Published on H-German (November, 2004) In making the analytical category "race" central to his investigation of Hitler's black victims, Clarence Lusane situates his book within an important new area of German Studies scholarship. Since the 1984 creative writing course taught at Berlin's Freie Universität by African-American poet Audre Lorde, who discovered a number of native-German-speaking women of color among her students and asked, "Who are you," "Afro-Germans" (or "Afro-Deutsche," a term coined in connection with Lorde's course) have taken the initiative to define themselves as a politically and culturally significant group in Germany. They have also been the subjects of a growing number of scholarly studies investigating the past and present experiences of the black populations of Germany. Certainly the initial catalyst for the Afro-German movement was the 1986 Frauenverlag volume that grew immediately out of Lorde's seminar, Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte (published in 1992 in English translation as Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out). -

Clarence Lusane ACES Cases, No. 2005.2

POLICING RACE AND TERRORISM IN THE UK: CLOSING THE RACIAL JUSTICE GAP By Clarence Lusane American Consortium on European Union Studies (ACES) EU Center of Excellence Washington, D.C. ACES Cases, No. 2005.2 Stephen J. Silvia, American University, editor Clarence Lusane is an Associate Professor at American University’s School of International Service. His current research interests are in international race politics, human rights, and electoral politics. He teaches courses in comparative race relations, modern social movements, comparative politics of African and the Caribbean, black political theory and political behavior, and drug policy and the social impact of drug abuse and trafficking. His most recent book is Hitler’s Black Victims: The Experiences of Afro-Germans, Africans, Afro-Europeans and African Americans During the Nazi Era (Routledge, Spring 2002). His other books include Race in the Global Era: African Americans at the Millennium (1997); No Easy Victories (1997), a history of black elected officials; African Americans at the Crossroads: The Restructuring of Black Leadership and the 1992 Elections (1994); The Struggle for Equal Education (1992); and Pipe Dream Blues: Racism and the War on Drugs (1991). Dr. Lusane is currently completing a book regarding Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice and their role in the construction of U.S. foreign policy. Copies of the case can be downloaded free of charge, and information on other cases in this series can be found, at the ACES website: www.american.edu/aces/cases.htm Copyright © 2005 American Consortium on European Union Studies Clarence Lusane Page 1 ACES CASES 2005/2 PC [Police Constable] Pulling: “A dog that’s born in a barn is still a dog, a Paki born in Britain is still a f****** Paki.” PC Hall: “I’ll stop him cos he’s a Paki. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 438 383 UD 033 353 AUTHOR Spriggs, William, Ed. TITLE The State of Black America, 1999: The Impact of Color-Consciousness in the United States. INSTITUTION National Urban League, Inc., New York, NY. ISBN ISBN-0-914758-98-5 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM National Urban League, Publications Dept., 120 Wall Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY ($24.95). Tel: 212-558-5316; Fax: 212-344-5189; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.nul.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Accountability; *Affirmative Action; *Blacks; Economic Factors; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Racial Attitudes; Urban Problems IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; Europe ABSTRACT The economic state of black America has never been healthier, vet persistent racial gaps leave African American unemployment at levels more typical of recession for whits in the United States. By challenging the predominant use of race, this compilation refocuses attention on the effects of discrimination and on the lost term "institutional racism." In so doing, it helps maintain the defense of affirmative action. These essays reinforce the position that race is not a biological category but a social category, one that becomes a marker for creating or denying access to wealth. The essays are: (1) "The Cancer Gap: Research Needs of African Americans" (Brian D. Smedley); (2) "Family Environment and Intergenerational Well-Being: Some Preliminary Results" (Patrick L. Mason); (3) "The State of Black Europe" (Clarence Lusane); (4) "Color-Blind Redistricting and the Efficacy of Black Representation" (Ronald Walters); (5) "Unfinished Business: African-American Political Economy during the Age of 'Color-Blind' Politics" (Rhonda M. -

Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" Was a "War on Blacks"

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2002 Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" Was a "War on Blacks" Kenneth B. Nunn University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth B. Nunn, Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" Was a "War on Blacks," 6 J. Gender Race & Just. 381 (2002), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/ 107 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the "War on Drugs" was a "War on Blacks" Kenneth B. Nunn* INTRODUCTION The War on Drugs I has had a devastating effect on African American communities nationwide. Throughout the drug war, African Americans have been disproportionately investigated, detained, searched, arrested and charged with the use, possession and sale of illegal drugs.2 Vast numbers of African Americans have been jailed and imprisoned pursuant to the nation's tough drug trafficking laws, implemented as part of the War on Drugs.3 Indeed, in some * Professor of Law, University of Florida, Levin College of Law.