Ultraroyalism in Toulouse Higgs, David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

France Safety (Safe Operating Mode) Water Damage

IMPEL - French Ministry of Sustainable Development - DGPR / SRT / BARPI - DREAL Champagne-Ardenne N° 43784 Flooding strikes a solvent recycling factory Natural hazards 7 May 2014 Rising waters Flood Buchères (Aube) Response / Emergency France Safety (safe operating mode) Water damage THE FACILITIES INVOLVED The site: ARR operator Chemical plant specialised in producing alcohol and recycling solvents, located in Buchères (Aube-10) Installed approximately 500 metres from the SEINE River in Buchères within the Aude Department, 5 km southeast of the city of Troyes, the company was affiliated with a French sugar manufacturing group possessing several plants across France. The Buchères site was specialised in: producing agricultural alcohol, regenerating alcohols and solvents, distilling vineyard co-products, and drying sewage sludge. The company had been authorised to store over 22,000 tonnes of flammable liquids, 9,000 tonnes of untreated wastes (including 500 tonnes of methanol), and 13,500 tonnes of treated wastes, in addition to producing 95,000 tonnes/year of regenerated solvents. For this reason, the site, located in a zone primarily dedicated to industrial activities, was ascribed an upper-tier SEVESO classification. The distillery, which relied on sugar beets, began operations in 1946. An alcohol regeneration activity was set up in 1996 that included workshops for regenerating residual alcohol originating from the perfume industry, pharmaceutical applications and fine chemicals production, along with several dehydration stations. Following the company's 2000 buyout by a French sugar manufacturing group, its solvent regeneration capacity, which represents the site's most important current activity, was expanded. In 2012, the site invested in a 15 MW biomass boiler. -

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

247 Communes Soumise À Zones IAHP 23/04/2021 14:00 ABIDOS

247 communes soumise à zones IAHP 23/04/2021 14:00 Situation Date indicative ZP Commune N° Insee Type de zone stabilisée ou remise en place coalescente évolutive palmipèdes ABIDOS 64003 ZS Stabilisée ABITAIN 64004 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 ABOS 64005 ZS Stabilisée ANDREIN 64022 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 ANOS 64027 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 ARANCOU 64031 ZS Évolutive ARAUJUZON 64032 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 ARAUX 64033 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 ARBERATS-SILLEGUE 64034 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 ARBOUET-SUSSAUTE 64036 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 ARGAGNON 64042 ZS Stabilisée ARGELOS 64043 ZS Stabilisée ARGET 64044 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 ARNOS 64048 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 ARRAUTE-CHARRITTE 64051 ZS Évolutive ARRICAU-BORDES 64052 ZS Stabilisée 11/05/2021 ARROS-DE-NAY 64054 ZS Stabilisée 17/05/2021 ARROSES 64056 ZS Stabilisée 11/05/2021 ARTHEZ-D'ASSON 64058 ZS Stabilisée 17/05/2021 ARTHEZ-DE-BEARN 64057 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 ARTIX 64061 ZS Stabilisée ARUDY 64062 ZS Stabilisée 17/05/2021 ARZACQ-ARRAZIGUET 64063 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 ASSON 64068 ZS Stabilisée 17/05/2021 ASTE-BEON 64069 ZS Stabilisée 17/05/2021 ASTIS 64070 ZS Stabilisée ATHOS-ASPIS 64071 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 AUBIN 64073 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 AUBOUS 64074 ZS Stabilisée 11/05/2021 AUDAUX 64075 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 AUGA 64077 ZSR Stabilisée 13/05/2021 AURIAC 64078 ZS Stabilisée AURIONS-IDERNES 64079 ZS Stabilisée 11/05/2021 AUTERRIVE 64082 ZS Évolutive AUTEVIELLE-ST-MARTIN-BIDEREN 64083 ZS Stabilisée 14/05/2021 AYDIE 64084 ZS Stabilisée 11/05/2021 AYDIUS 64085 ZS -

Infected Areas As on 26 January 1989 — Zones Infectées an 26 Janvier 1989 for Criteria Used in Compiling This List, See No

Wkty Epidem Rec No 4 - 27 January 1989 - 26 - Relevé éptdém hebd . N°4 - 27 janvier 1989 (Continued from page 23) (Suite de la page 23) YELLOW FEVER FIÈVRE JAUNE T r in id a d a n d T o b a g o (18 janvier 1989). — Further to the T r i n i t é - e t -T o b a g o (18 janvier 1989). — A la suite du rapport report of yellow fever virus isolation from mosquitos,* 1 the Min concernant l’isolement du virus de la fièvre jaune sur des moustiques,1 le istry of Health advises that there are no human cases and that the Ministère de la Santé fait connaître qu’il n’y a pas de cas humains et que risk to persons in urban areas is epidemiologically minimal at this le risque couru par des personnes habitant en zone urbaine est actuel time. lement minime. Vaccination Vaccination A valid certificate of yellow fever vaccination is N O T required Il n’est PAS exigé de certificat de vaccination anuamarile pour l’en for entry into Trinidad and Tobago except for persons arriving trée à la Trinité-et-Tobago, sauf lorsque le voyageur vient d’une zone from infected areas. (This is a standing position which has infectée. (C’est là une politique permanente qui n ’a pas varié depuis remained unchanged over the last S years.) Sans.) On the other hand, vaccination against yellow fever is recom D’autre part, la vaccination antiamarile est recommandée aux per mended for those persons coming to Trinidad and Tobago who sonnes qui, arrivant à la Trinité-et-Tobago, risquent de se rendre dans may enter forested areas during their stay ; who may be required des zones de -

Échappées Belles En Haute-Garonne

ÉCHAPPÉES BELLES EN HAUTE-GARONNE Actualité Proximité Sorties Portrait N° 149+ supplément été JUIN / JUILLET / AOÛT 2018 HAUTE-GARONNE MAGAZINE MA HAUTE-GARONNE N°149 22 PRÈS DE CHEZ VOUS 34 DÉCRYPTAGE JUIN / JUILLET / AOÛT 2018 36 EXPRESSIONS POLITIQUES PUBLICATION DU CONSEIL DÉPARTEMENTAL DE LA HAUTE-GARONNE 1, boulevard de la Marquette 31090 Toulouse Cedex 9 Tél. : 05 34 33 32 31 Antenne de Saint-Gaudens 1, espace Pégot 31800 Saint-Gaudens Tél. : 05 62 00 25 00 Mail : [email protected] Site : haute-garonne.fr - Directeur de la publication GEORGES MÉRIC - Coordination FRANÇOIS BOURSIER - Rédaction en chef AURÉLIE RENNE - Ont participé à ce numéro PASCAL ALQUIER, ARTHUR DIAS, ÉMILIE GILMER, L’ACTU ÉLODIE PAGÈS, MARIEN REGNAULT ET BÉNÉDICTE SOULA - 04 LE ZAPPING Photos 10 À LA UNE SHANNON AOUATAH, LOÏC BEL, THOMAS BIARNEIX, AURÉLIEN FERREIRA, RÉMY GABALDA, ALIS MIREBEAU, ALEXANDRE OLLIER, FLORIAN RACACHÉ, HÉLÈNE RESSAYRES ET ROMAIN SAADA, SAUF FOTOLIA OU MENTION SPÉCIALE - Conception graphique et mise en page LE DOSSIER CORINNE MASSA ET STUDIO OGHAM 14 ECHAPPÉES BELLES - Impression EN HAUTE-GARONNE AGIR GRAPHIC BP 52 207 - 53022 Laval cedex 9 www.agir-graphic.fr - Numéro ISSN 2116-2956 La reproduction même partielle de tout document publié dans ce journal est interdite sans autorisation 683 000 exemplaires Publication gratuite NOUS CONTACTER [email protected] NOUS LIRE haute-garonne.fr/magazine NOUS ÉCOUTER haute-garonne.fr/magazineaudio NOUS VOIR youtube.com/31hautegaronne SUIVEZ-NOUS MES LOISIRS 38 CULTURE ET PATRIMOINE 44 L’AGENDA DES SORTIES 47 TEMPS LIBRE 48 LE PORTRAIT TROIS QUESTIONS À GEORGES MÉRIC PRÉSIDENT DU CONSEIL DÉPARTEMENTAL DE LA HAUTE-GARONNE Depuis trois ans, pourquoi le Conseil départemental Qu’en est-il du soutien aux sites majeurs de Haute- de la Haute-Garonne fait-il du tourisme une de ses Garonne ? priorités ? Aurignac, Laréole, Montmaurin, Saint-Bertrand-de- GEORGES MÉRIC : Le tourisme est un formidable Comminges / Valcabrère, la forêt de Buzet représentent levier pour renforcer l’attractivité, créer des activités des enjeux forts. -

Macroeconomic Features of the French Revolution Author(S): Thomas J

Macroeconomic Features of the French Revolution Author(s): Thomas J. Sargent and François R. Velde Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 103, No. 3 (Jun., 1995), pp. 474-518 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2138696 . Accessed: 12/04/2013 15:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Political Economy. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.199.207.139 on Fri, 12 Apr 2013 15:49:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Macroeconomic Features of the French Revolution Thomas J. Sargent University of Chicago and Hoover Institution, Stanford University Frangois R. Velde Johns Hopkins University This paper describes aspects of the French Revolution from the perspective of theories about money and government budget con- straints. We describe how unpleasant fiscal arithmetic gripped the Old Regime, how the Estates General responded to reorganize France'sfiscal affairs, and how fiscal exigencies impelled the Revo- lution into a procession of monetary experiments ending in hyper- inflation. -

About Fanjeaux, France Perched on the Crest of a Hill in Southwestern

About Fanjeaux, France Perched on the crest of a hill in Southwestern France, Fanjeaux is a peaceful agricultural community that traces its origins back to the Romans. According to local legend, a Roman temple to Jupiter was located where the parish church now stands. Thus the name of the town proudly reflects its Roman heritage– Fanum (temple) Jovis (Jupiter). It is hard to imagine that this sleepy little town with only 900 inhabitants was a busy commercial and social center of 3,000 people during the time of Saint Dominic. When he arrived on foot with the Bishop of Osma in 1206, Fanjeaux’s narrow streets must have been filled with peddlers, pilgrims, farmers and even soldiers. The women would gather to wash their clothes on the stones at the edge of a spring where a washing place still stands today. The church we see today had not yet been built. According to the inscription on a stone on the south facing outer wall, the church was constructed between 1278 and 1281, after Saint Dominic’s death. You should take a walk to see the church after dark when its octagonal bell tower and stone spire, crowned with an orb, are illuminated by warm orange lights. This thick-walled, rectangular stone church is an example of the local Romanesque style and has an early Gothic front portal or door (the rounded Romanesque arch is slightly pointed at the top). The interior of the church was modernized in the 18th century and is Baroque in style, but the church still houses unusual reliquaries and statues from the 13th through 16th centuries. -

The Dragonfly Fauna of the Aude Department (France): Contribution of the ECOO 2014 Post-Congress Field Trip

Tome 32, fascicule 1, juin 2016 9 The dragonfly fauna of the Aude department (France): contribution of the ECOO 2014 post-congress field trip Par Jean ICHTER 1, Régis KRIEG-JACQUIER 2 & Geert DE KNIJF 3 1 11, rue Michelet, F-94200 Ivry-sur-Seine, France; [email protected] 2 18, rue de la Maconne, F-73000 Barberaz, France; [email protected] 3 Research Institute for Nature and Forest, Rue de Clinique 25, B-1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] Received 8 October 2015 / Revised and accepted 10 mai 2016 Keywords: ATLAS ,AUDE DEPARTMENT ,ECOO 2014, EUROPEAN CONGRESS ON ODONATOLOGY ,FRANCE ,LANGUEDOC -R OUSSILLON ,ODONATA , COENAGRION MERCURIALE ,GOMPHUS FLAVIPES ,GOMPHUS GRASLINII , GOMPHUS SIMILLIMUS ,ONYCHOGOMPHUS UNCATUS , CORDULEGASTER BIDENTATA ,MACROMIA SPLENDENS ,OXYGASTRA CURTISII ,TRITHEMIS ANNULATA . Mots-clés : A TLAS ,AUDE (11), CONGRÈS EUROPÉEN D 'ODONATOLOGIE ,ECOO 2014, FRANCE , L ANGUEDOC -R OUSSILLON ,ODONATES , COENAGRION MERCURIALE ,GOMPHUS FLAVIPES ,GOMPHUS GRASLINII ,GOMPHUS SIMILLIMUS , ONYCHOGOMPHUS UNCATUS ,CORDULEGASTER BIDENTATA ,M ACROMIA SPLENDENS ,OXYGASTRA CURTISII ,TRITHEMIS ANNULATA . Summary – After the third European Congress of Odonatology (ECOO) which took place from 11 to 17 July in Montpellier (France), 21 odonatologists from six countries participated in the week-long field trip that was organised in the Aude department. This area was chosen as it is under- surveyed and offered the participants the possibility to discover the Languedoc-Roussillon region and the dragonfly fauna of southern France. In summary, 43 sites were investigated involving 385 records and 45 dragonfly species. These records could be added to the regional database. No less than five species mentioned in the Habitats Directive ( Coenagrion mercuriale , Gomphus flavipes , G. -

4.8 Cu. Ft. History the French Revolution Pamphlets Collec

French Revolution Pamphlets Collection 544 Items, 1779-1815 16 Boxes; 4.8 cu. ft. History The French Revolution Pamphlets Collection was purchased in 1973 from Mrs. Frances Reynolds. It was originally acquired by Ball State University to assist an increasing number of history and French students in their research and studies. It was also purchased in the hopes that Ball State’s Ph.D. program in History would be approved in the same year. It was meant to be a foundation for research in the field of modern Europe. At the time of acquisition, Dr. Richard Wires, chairman of the Department of History, wrote in support of the purchase, stating "… we have an increasing number of students who do work in this period for History and French credit and such source material is extremely valuable for their research and studies." Though the Ph.D. program never came to fruition, the French Revolution Pamphlet Collection remains an important resource for students and researchers. The effects of the French Revolution were far reaching and global. The resulting wars propelled Britain to global dominance. France’s navy was in shambles and its empire lost. Spain and Holland were broken as imperial powers. Radical ideas on rights, citizenship, and role of the state developed. The revolution heavily influenced conceptions of liberty and democracy. It also promoted nationalism and citizenship. Many historians consider the French Revolution as the beginning of Modern Europe. The example of the American Revolution and the growth of new ideas amongst the Bourgeoisie began to stir up revolutionary ideas among the French. -

Pleasure and Peril: Shaping Children's Reading in the Early Twentieth Century

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2006 Pleasure and Peril: Shaping Children's Reading in the Early Twentieth Century Wendy Korwin College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Korwin, Wendy, "Pleasure and Peril: Shaping Children's Reading in the Early Twentieth Century" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626508. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-n1yh-kj07 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLEASURE AND PERIL: Shaping Children’s Reading in the Early Twentieth Century A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Wendy Korwin 2006 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Wjmdy Korwin Approved by the Committee, April 2006 Leisa Meyer, Chair rey Gundaker For Fluffy and Huckleberry TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments v List of Figures vi Abstract vii Introduction 2 Chapter I. Prescriptive Literature and the Reproduction of Reading 9 Chapter II. Public Libraries and Consumer Lessons 33 Notes 76 Bibliography 82 Vita 90 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank just about everyone who spent time with me and with my writing over the last year and a half. -

Lignes Régulières

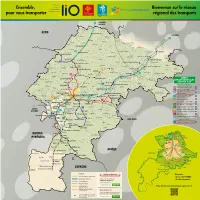

Ensemble, Bienvenue sur le réseau pour vous transporter régional des transports SAMATAN TOULOUSE Boissède Molas GERS TOULOUSE Puymaurin Ambax Sénarens Riolas Nénigan D 17 Pouy-de-Touges Lunax Saint-Frajou Gratens Péguilhan Fabas 365 Castelnau-Picampeau Polastron Latte-Vigordane Lussan-Adeilhac Le Fousseret Lacaugne Eoux Castéra-Vignoles Francon Rieux-Volvestre Boussan Latrape 342 Mondavezan Nizan-Gesse Lespugue 391 D 62 Bax Castagnac Sarrecave Marignac-Laspeyres Goutevernisse Canens Sarremezan 380 Montesquieu-Volvestre 344 Peyrouzet D 8 Larroque Saint- LIGNES Christaud Gouzens Cazaril-Tamboures DÉPARTEMENTALES Montclar-de-Comminges Saint-Plancard Larcan SECTEUR SUD Auzas Le Plan D 5 320 Lécussan Lignes régulières Sédeilhac Sepx Montberaud Ausseing 342 L’ISLE-EN-DODON - SAINT-GAUDENS Le Cuing Lahitère 344 BOULOGNE - SAINT-GAUDENS Franquevielle Landorthe 365 BOULOGNE - L'ISLE-EN-DODON - Montbrun-Bocage SAMATAN - TOULOUSE Les Tourreilles 379 LAVELANET - MAURAN - CAZÈRES 394 D 817 379 SAINT-GAUDENS 397 380 CAZÈRES - NOÉ - TOULOUSE D 117 391 ALAN - AURIGNAC - SAINT-GAUDENS Touille 392 MONCAUP - ASPET - SAINT-GAUDENS His 393 392 Ganties MELLES - SAINT-BÉAT - SAINT-GAUDENS TARBES D 9 Rouède 394 LUCHON - MONTRÉJEAU - SAINT-GAUDENS N 125 398 BAYONNE 395 LES(Val d’Aran) - BARBAZAN - SAINT-GAUDENS Castelbiague Estadens 397 MANE - SAINT-GAUDENS Saleich 398 MONTRÉJEAU - BARBAZAN - SAINT-GAUDENS Chein-Dessus SEPTEMBRE 2019 - CD31/19/7/42845 395 393 Urau Francazal SAINT-GIRONS Navette SNCF D 5 Arbas 320 AURIGNAC - SAINT-MARTORY - BOUSSENS SNCF Fougaron -

If There Is No Conversation, We'll Be Back

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons November 2015 11-17-2015 The aiD ly Gamecock, Tuesday, November 17, 2015 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_nov Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, Tuesday, November 17, 2015" (2015). November. 7. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_nov/7 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2015 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in November by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEWS 1 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2015 VOL. 106, NO. 42 ● SINCE 1908 Rivalry week begins Brittany Franceschina @BRITTA_FRAN Clemson-Carolina Rivalry Week kicked off this Monday with the 31st annual Carolina Clemson Blood Drive as well as the CarolinaCan Food Drive. Both of these events give students the opportunity to not only give back to the community, but to beat Clemson. The Carolina-Clemson Blood Drive, going on from Nov. 16 to 20 at various locations around campus, Madison MacDonald / THE DAILY GAMECOCK encourages students to donate Third-year biochemistry and molecular biology student Alkeiver Cannon (center) voiced her concerns Monday with @USC2020Vision. blood through the Red Cross. In the past the Carolina Greek Programming Board organized it, but it is now transforming ‘If there is no conversation, into a student organization. The Blood Drive in association with the Red Cross also aims to educate students we’ll be back’ on the importance of donating blood.