Moncerdac-41:Layout 1 3-01-2017 17:26 Pagina II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAN POLITICS DURING the JUGURTHINE WAR by PATRICIA EPPERSON WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State

ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR By PATRICIA EPPERSON ,WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1975 SEP Ji ·J75 ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR Thesis Approved: . Dean of the Graduate College 91648 ~31 ii PREFACE The Jugurthine War occurred within the transitional period of Roman politics between the Gracchi and the rise of military dictators~ The era of the Numidian conflict is significant, for during that inter val the equites gained political strength, and the Roman army was transformed into a personal, professional army which no longer served the state, but dedicated itself to its commander. The primary o~jec tive of this study is to illustrate the role that political events in Rome during the Jugurthine War played in transforming the Republic into the Principate. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Neil Hackett, for his patient guidance and scholarly assistance, and to also acknowledge the aid of the other members of my counnittee, Dr. George Jewsbury and Dr. Michael Smith, in preparing my final draft. Important financial aid to my degree came from the Dr. Courtney W. Shropshire Memorial Scholarship. The Muskogee Civitan Club offered my name to the Civitan International Scholarship Selection Committee, and I am grateful for their ass.istance. A note of thanks is given to the staff of the Oklahoma State Uni versity Library, especially Ms. Vicki Withers, for their overall assis tance, particularly in securing material from other libraries. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of ANCIENT ROME a Timeline from 753 BC to 337 AD, Looking at the Successive Kings, Politicians, and Emperors Who Ruled Rome’S Expanding Empire

Rome: A Virtual Tour of the Ancient City A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANCIENT ROME A timeline from 753 BC to 337 AD, looking at the successive kings, politicians, and emperors who ruled Rome’s expanding empire. 21st April, Rome's Romulus and Remus featured in legends of Rome's foundation; 753 BC mythological surviving accounts, differing in details, were left by Dionysius of foundation Halicarnassus, Livy, and Plutarch. Romulus and Remus were twin sons of the war god Mars, suckled and looked-after by a she-wolf after being thrown in the river Tiber by their great-uncle Amulius, the usurping king of Alba Longa, and drifting ashore. Raised after that by the shepherd Faustulus and his wife, the boys grew strong and were leaders of many daring adventures. Together they rose against Amulius, killed him, and founded their own city. They quarrelled over its site: Romulus killed Remus (who had preferred the Aventine) and founded his city, Rome, on the Palatine Hill. 753 – Reign of Kings From the reign of Romulus there were six subsequent kings from the 509 BC 8th until the mid-6th century BC. These kings are almost certainly legendary, but accounts of their reigns might contain broad historical truths. Roman monarchs were served by an advisory senate, but held supreme judicial, military, executive, and priestly power. The last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown and a republican constitution installed in his place. Ever afterwards Romans were suspicious of kingly authority - a fact that the later emperors had to bear in mind. 509 BC Formation of Tarquinius Superbus, the last king was expelled in 509 BC. -

Fractures: Political Identity in the Fall of the Roman Republic by Juan De

Fractures: Political Identity in the Fall of the Roman Republic by Juan De Dios Vela III, B.A. A Thesis In History Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Gary Edward Forsythe Chair of Committee Dr. John McDonald Howe Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School August, 2019 Copyright 2019, Juan De Dios Vela Texas Tech University, Juan De Dios Vela III, August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I: FOUNDATIONS..................................................................................... 13 Part one: Political Institutions ..................................................................................... 13 Part Two: Citizens, Latins, Colonies and the Social Web .................................... 23 Part Three: Magistrates and Local Control ........................................................... 26 Part Four: Patrons and Clients .................................................................................... 28 CHAPTER II: THE FIRST CRACKS ......................................................................... 32 The Gracchan Seditions ....................................................................................... 32 Impotent Interlopers ............................................................................................ -

1 Understanding Historical Change: Rome HIST 1220.R21, Summer

Understanding Historical Change: Rome HIST 1220.R21, Summer 2016 Adjunct Professor Matthew Keil, PhD TWR 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM Dealy Hall 202, Rose Hill Email: [email protected] [email protected] (preferred) Web: MagisterKeil.com Office Hours by appointment in Faculty Memorial Hall , 428D Course Overview and Scope Within the ever-fractious saga of European history, ancient Rome looms unchallenged as the continent’s greatest period of unity and stability. At its zenith in the second century AD, the Roman Empire stretched from Hadrian’s Wall in Northern England to the Euphrates River in Syria, and from the Black Sea in the East to the Atlantic Ocean in the West. So tremendous in fact was the achievement of Rome in creating and sustaining this enormous empire that the very notion of Rome has left an indelible mark on all subsequent nations which are bearers of Western civilization. European rulers as far apart in time as Charlemagne, Napoleon, and Hitler have all consciously sought to position their respective dominions in relation to the Roman exemplar, and indeed the historical precedent for this positioning was first laid by the immediate successors to Rome's empire, the "barbarian" tribes who laid it waste, yet who nevertheless often called themselves Romans; after them, and for most of its subsequent history, Europe has seen some form of the Holy Roman Empire. It was not just in Europe, however, but also on the continents of Africa and Asia that Roman subjects swore their obedience to a single political system, acquiesced to the jurisprudence of a single law-code, and sought entrance into a single, distinct cultural community, despite their own often deep linguistic, religious, and regional diversity. -

The Military Reforms of Gaius Marius in Their Social, Economic, and Political Context by Michael C. Gambino August, 2015 Directo

The Military Reforms of Gaius Marius in their Social, Economic, and Political Context By Michael C. Gambino August, 2015 Director of Thesis: Dr. Frank Romer Major Department: History Abstract The goal of this thesis is, as the title affirms, to understand the military reforms of Gaius Marius in their broader societal context. In this thesis, after a brief introduction (Chap. I), Chap. II analyzes the Roman manipular army, its formation, policies, and armament. Chapter III examines Roman society, politics, and economics during the second century B.C.E., with emphasis on the concentration of power and wealth, the legislative programs of Ti. And C. Gracchus, and the Italian allies’ growing demand for citizenship. Chap. IV discusses Roman military expansion from the Second Punic War down to 100 B.C.E., focusing on Roman military and foreign policy blunders, missteps, and mistakes in Celtiberian Spain, along with Rome’s servile wars and the problem of the Cimbri and Teutones. Chap. V then contextualizes the life of Gaius Marius and his sense of military strategy, while Chap VI assesses Marius’s military reforms in his lifetime and their immediate aftermath in the time of Sulla. There are four appendices on the ancient literary sources (App. I), Marian consequences in the Late Republic (App. II), the significance of the legionary eagle standard as shown during the early principate (App. III), and a listing of the consular Caecilii Metelli in the second and early first centuries B.C.E. (App. IV). The Marian military reforms changed the army from a semi-professional citizen militia into a more professionalized army made up of extensively trained recruits who served for longer consecutive terms and were personally bound to their commanders. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Distortions in the Historical Record Concerning Ager Publicus, Leges Agrariae, and the Gracchi Maria Therese Jeffrey Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2011-3 Distortions in the Historical Record Concerning Ager Publicus, Leges Agrariae, and the Gracchi Maria Therese Jeffrey Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey, Maria Therese, "Distortions in the Historical Record Concerning Ager Publicus, Leges Agrariae, and the Gracchi" (2011). Honors Bachelor of Arts. 22. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/22 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Distortions in the Historical Record Concerning Ager Publicus, Leges Agrariae, and the Gracchi Maria Jeffrey Introduction: Scholarship on the Gracchi is largely based on the accounts of Plutarch and Appian, historians who were far removed temporally from the Gracchi themselves. It is not known from which sources Plutarch and Appian derive their accounts, which presents problems for the modern historian aiming to determine historical fact. The ancient sources do not equip the modern historian to make many definitive claims about the Gracchan agrarian reform, much less about the motives of the Gracchi themselves. Looking to tales of earlier agrarian reform through other literary sources as well as exploring the types of land in question and the nature of the agrarian crisis through secondary sources also yields ambiguous results. -

The Lex Sempronia Agraria: a Soldier's Stipendum

THE LEX SEMPRONIA AGRARIA: A SOLDIER’S STIPENDUM by Raymond Richard Hill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Raymond Richard Hill ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Raymond Richard Hill Thesis Title: The Lex Sempronia Agraria: A Soldier’s Stipendum Date of Final Oral Examination: 16 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Raymond Richard Hill, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Lee Ann Turner, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION To Kessa for all of her love, patience, guidance and support. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Dr. Katherine Huntley for her hours spent proofing my work, providing insights and making suggestions on research materials. To Dr. Charles Matson Odahl who started this journey with me and first fired my curiosity about the Gracchi. To the history professors of Boise State University who helped me become a better scholar. v ABSTRACT This thesis examines mid-second century BCE Roman society to determine the forces at work that resulted in the passing of a radical piece of legislation known as the lex Sempronia agraria. -

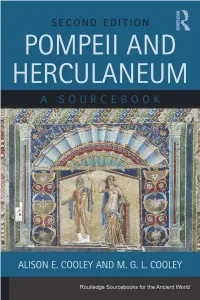

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

A Fork in the Road: the Catilinarian Conspiracy's Impact

A Fork in the Road: The Catilinarian Conspiracy‘s Impact on Cicero‘s relationships with Pompey, Crassus` and Caesar Jeffrey Larson History 499: Senior Thesis June 13, 2011 © Jeffrey Larson, 2011 1 But concerning friendship, all, to a man, think the same thing: those who have devoted themselves to public life; those who find their joy in science and philosophy; those who manage their own business free from public cares; and, finally, those who are wholly given up to sensual pleasures — all believe that without friendship life is no life at all. .1 The late Roman Republic was filled with crucial events which shaped not only the political environment of the Republic, but also altered the personal and political relationships of the individuals within that Republic. Four of the most powerful, and most discussed, characters of this time are Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BC – 43 BC), Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (106 BC – 48 BC), Marcus Licinius Crassus (c. 115 BC – 53 BC), and Gaius Julius Caesar (c. 100 BC – 44 BC). These men often crossed paths and some even had close friendships with each other. Other than Pompeius, better known as Pompey, all the aforementioned individuals were involved, or reportedly involved, in one event which had profound effects on the personal and political relationships of all four individuals. This event is known as the Catilinarian Conspiracy of 63 BC. The Catilinarian Conspiracy was a pivotal episode in the politics of the Late Roman Republic that damaged both the political and personal relationships of Cicero, Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar. Politics in the Roman Republic was dominated by a small number of members of the senatorial class.