Recommendations for Euthanasia of Experimental Animals: Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analgesia and Sedation in Hospitalized Children

Analgesia and Sedation in Hospitalized Children By Elizabeth J. Beckman, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCCCP, BCPPS Reviewed by Julie Pingel, Pharm.D., BCPPS; and Brent A. Hall, Pharm.D., BCPPS LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Evaluate analgesics and sedative agents on the basis of drug mechanism of action, pharmacokinetic principles, adverse drug reactions, and administration considerations. 2. Design an evidence-based analgesic and/or sedative treatment and monitoring plan for the hospitalized child who is postoperative, acutely ill, or in need of prolonged sedation. 3. Design an analgesic and sedation treatment and monitoring plan to minimize hyperalgesia and delirium and optimize neurodevelopmental outcomes in children. INTRODUCTION ABBREVIATIONS IN THIS CHAPTER Pain, anxiety, fear, distress, and agitation are often experienced by GABA γ-Aminobutyric acid children undergoing medical treatment. Contributory factors may ICP Intracranial pressure include separation from parents, unfamiliar surroundings, sleep dis- PAD Pain, agitation, and delirium turbance, and invasive procedures. Children receive analgesia and PCA Patient-controlled analgesia sedatives to promote comfort, create a safe environment for patient PICU Pediatric ICU and caregiver, and increase patient tolerance to medical interven- PRIS Propofol-related infusion tions such as intravenous access placement or synchrony with syndrome mechanical ventilation. However, using these agents is not without Table of other common abbreviations. risk. Many of the agents used for analgesia and sedation are con- sidered high alert by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices because of their potential to cause significant patient harm, given their adverse effects and the development of tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms. Added layers of complexity include the ontogeny of the pediatric patient, ongoing disease processes, and presence of organ failure, which may alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of these medications. -

Euthanasia of Experimental Animals

EUTHANASIA OF EXPERIMENTAL ANIMALS • *• • • • • • • *•* EUROPEAN 1COMMISSIO N This document has been prepared for use within the Commission. It does not necessarily represent the Commission's official position. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int) Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1997 ISBN 92-827-9694-9 © European Communities, 1997 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Belgium European Commission EUTHANASIA OF EXPERIMENTAL ANIMALS Document EUTHANASIA OF EXPERIMENTAL ANIMALS Report prepared for the European Commission by Mrs Bryony Close Dr Keith Banister Dr Vera Baumans Dr Eva-Maria Bernoth Dr Niall Bromage Dr John Bunyan Professor Dr Wolff Erhardt Professor Paul Flecknell Dr Neville Gregory Professor Dr Hansjoachim Hackbarth Professor David Morton Mr Clifford Warwick EUTHANASIA OF EXPERIMENTAL ANIMALS CONTENTS Page Preface 1 Acknowledgements 2 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Objectives of euthanasia 3 1.2 Definition of terms 3 1.3 Signs of pain and distress 4 1.4 Recognition and confirmation of death 5 1.5 Personnel and training 5 1.6 Handling and restraint 6 1.7 Equipment 6 1.8 Carcass and waste disposal 6 2. General comments on methods of euthanasia 7 2.1 Acceptable methods of euthanasia 7 2.2 Methods acceptable for unconscious animals 15 2.3 Methods that are not acceptable for euthanasia 16 3. Methods of euthanasia for each species group 21 3.1 Fish 21 3.2 Amphibians 27 3.3 Reptiles 31 3.4 Birds 35 3.5 Rodents 41 3.6 Rabbits 47 3.7 Carnivores - dogs, cats, ferrets 53 3.8 Large mammals - pigs, sheep, goats, cattle, horses 57 3.9 Non-human primates 61 3.10 Other animals not commonly used for experiments 62 4. -

Diluted Isoflurane As a Suitable Alternative for Diethyl Ether for Rat Anaesthesia in Regular Toxicology Studies

FULL PAPER Laboratory Aminal Science Diluted Isoflurane as a Suitable Alternative for Diethyl ether for Rat Anaesthesia in Regular Toxicology Studies Toshiaki NAGATE1)*, Tomonobu CHINO1), Chizuru NISHIYAMA1), Daisuke OKUHARA1), Toru TAHARA1), Yoshimasa MARUYAMA1), Hiroko KASAHARA1), Kayoko TAKASHIMA1), Sayaka KOBAYASHI1), Yoshiyuki MOTOKAWA1), Shin-ichi MUTO1) and Junji KURODA1) 1)Toxicology Research Laboratory, R&D, Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 2320–1 Maki, Hotaka, Azumino-City, Nagano-Pref. 399–8305, Japan (Received 6 October 2006/Accepted 20 July 2007) ABSTRACT. Despite its explosive properties and toxicity to both animals and humans, diethyl ether is an agent long used in Japan in the anaesthesia jar method of rat anaesthetises. However, in response to a recent report from the Science Council of Japan condemning diethyl ether as acceptable practice, we searched for an alternative rat anaesthesia method that provided data continuous with pre-existing regular toxicology studies already conducted under diethyl ether anaesthesia. For this, we examined two candidates; 30% isoflurane diluted with propylene glycol and pentobarbitone. Whereas isoflurane is considered to be one of the representatives of modern volatile anaesthetics, the method of propylene glycol-diluted 30% isoflurane used in this study was our modification of a recently reported method revealed to have several advantages as an inhalation anaesthesia. Intraperitoneal pentobarbitone has long been accepted as a humane method in laboratory animal anaesthesiology. These 2 modalities were scrutinized in terms of consistency of haematology and blood chemistry with previous results using ether. We found that pentobarbitone required a much longer induction time than diethyl ether, which is suspected to be the cause of fluctuations in several haematological and blood chemical results. -

The Cardiorespiratory and Anesthetic Effects of Clinical and Supraclinical

THE CARDIORESPIRATORY AND ANESTHETIC EFFECTS OF CLINICAL AND SUPRA CLINICAL DOSES OF ALF AXALONE IN CYCLODEXTRAN IN CATS AND DOGS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura L. Nelson, B.S., D.V.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Professor Jonathan Dyce, Adviser Professor William W. Muir III Professor Shane Bateman If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants. lmac Ne1vton (1642-1727) Copyright by Laura L. Nelson 2007 11 ABSTRACT The anesthetic properties of steroid hormones were first identified in 1941, leading to the development of neurosteroids as clinical anesthetics. CT-1341 was developed in the early 1970’s, featuring a combination of two neurosteroids (alfaxalone and alphadolone) solubilized in Cremophor EL®, a polyethylated castor oil derivative that allows hydrophobic compounds to be carried in aqueous solution as micelles. Though also possessing anesthetic properties, alphadolone was included principally to improve the solubility of alfaxalone. CT-1341, marketed as Althesin® and Saffan®, was characterized by smooth anesthetic induction and recovery in many species, a wide therapeutic range, and no cumulative effects with repeated administration. Its cardiorespiratory effects in humans and cats were generally mild. However, it induced severe hypersensitivity reactions in dogs, with similar reactions occasionally occurring in cats and humans. The hypersensitivity reactions associated with this formulation were linked to Cremophor EL®, leading to the discontinuation of Althesin® and some other Cremophor®-containing anesthetics. More recently, alternate vehicles for hydrophobic drugs have been developed, including cyclodextrins. -

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block III Lectures 2013-14

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block III Lectures 2013‐14 66. Hypothalamic/pituitary Hormones ‐ Rana 67. Estrogens and Progesterone I ‐ Rana 68. Estrogens and Progesterone II ‐ Rana 69. Androgens ‐ Rana 70. Thyroid/Anti‐Thyroid Drugs – Patel 71. Calcium Metabolism – Patel 72. Adrenocorticosterioids and Antagonists – Clipstone 73. Diabetes Drugs I – Clipstone 74. Diabetes Drugs II ‐ Clipstone Pharmacology & Therapeutics Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones, March 20, 2014 Lecture Ajay Rana, Ph.D. Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones Date: Thursday, March 20, 2014-8:30 AM Reading Assignment: Katzung, Chapter 37 Key Concepts and Learning Objectives To review the physiology of neuroendocrine regulation To discuss the use neuroendocrine agents for the treatment of representative neuroendocrine disorders: growth hormone deficiency/excess, infertility, hyperprolactinemia Drugs discussed Growth Hormone Deficiency: . Recombinant hGH . Synthetic GHRH, Recombinant IGF-1 Growth Hormone Excess: . Somatostatin analogue . GH receptor antagonist . Dopamine receptor agonist Infertility and other endocrine related disorders: . Human menopausal and recombinant gonadotropins . GnRH agonists as activators . GnRH agonists as inhibitors . GnRH receptor antagonists Hyperprolactinemia: . Dopamine receptor agonists 1 Pharmacology & Therapeutics Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones, March 20, 2014 Lecture Ajay Rana, Ph.D. 1. Overview of Neuroendocrine Systems The neuroendocrine -

Pharmacokinetics of Ovarian Steroids in Sprague-Dawley Rats After Acute Exposure to 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo- P-Dioxin (TCDD)

Vol. 3, No. 2 131 ORIGINAL PAPER Pharmacokinetics of ovarian steroids in Sprague-Dawley rats after acute exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo- p-dioxin (TCDD) Brian K. Petroff 1,2,3 and Kemmy M. Mizinga4 2Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology,Physiology, 3Center for Reproductive Sciences, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160. 4Department of Pharmacology,Pharmacology, University of Health Sciences, Kansas City,City, MO 64106 Received: 3 June 2003; accepted: 28 June 2003 SUMMARY 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) induces abnormalities in ste- roid-dependent processes such as mammary cell proliferation, gonadotropin release and maintenance of pregnancy. In the current study, the effects of TCDD on the pharmacokinetics of 17ß-estradiol and progesterone were examined. Adult Sprague-Dawley rats were ovariectomized and pretreated with TCDD (15 µg/kg p.o.) or vehicle. A single bolus of 17ß-estradiol (E2, 0.3 µmol/kg i.v.) or progesterone (P4, 6 µmol/kg i.v.) was administered 24 hours after TCDD and blood was collected serially from 0-72 hours post- injection. Intravenous E2 and P4 in DMSO vehicle had elimination half-lives of approximately 10 and 11 hours, respectively. TCDD had no signifi cant effect on the pharmacokinetic parameters of P4. The elimination constant 1Corresponding author: Center for Reproductive Sciences, Department of Molecular and Integra- tive Physiology, University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2003 by the Society for Biology of Reproduction 132 TCDD and ovarian steroid pharmacokinetics and clearance of E2 were decreased by TCDD while the elimination half-life, volume of distribution and area under the time*concentration curve were not altered signifi cantly. -

Clinical Anesthesia and Analgesia in Fish

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 1-2012 Clinical Anesthesia and Analgesia in Fish Lynne U. Sneddon University of Liverpool Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_vsm Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Veterinary Toxicology and Pharmacology Commons Recommended Citation Sneddon, L. U. (2012). Clinical anesthesia and analgesia in fish. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 21(1), 32-43. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clinical Anesthesia and Analgesia in Fish Lynne U. Sneddon University of Liverpool KEYWORDS Analgesics, anesthetic drugs, fish, local anesthetics, opioids, NSAIDs ABSTRACT Fish have become a popular experimental model and companion animal, and are also farmed and caught for food. Thus, surgical and invasive procedures in this animal group are common, and this review will focus on the anesthesia and analgesia of fish. A variety of anesthetic agents are commonly applied to fish via immersion. Correct dosing can result in effective anesthesia for acute procedures as well as loss of consciousness for surgical interventions. Dose and anesthetic agent vary between species of fish and are further confounded by a variety of physiological parameters (e.g., body weight, physiological stress) as well as environmental conditions (e.g., water temperature). Combination anesthesia, where 2 anesthetic agents are used, has been effective for fish but is not routinely used because of a lack of experimental validation. Analgesia is a relatively underexplored issue in regards to fish medicine. -

IV Induction Agents

Intravenous drugs used for the induction of anaesthesia Dr Tom Lupton, Specialist Registrar in Anaesthesia Dr Oliver Pratt, Consultant Anaesthetist Salford Royal Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK Key questions This tutorial reviews the basic pharmacology of common intravenous (IV) anaesthetic drugs. By the end of the tutorial, you should be able to decide on the most appropriate drug to use in the situations below and for what reason: 1. A patient with intestinal obstruction requires an emergency laparotomy. 2. A patient with a history of throat cancer, showing marked stridor and signs of respiratory distress, requires a tracheostomy. 3. A patient requiring a burn dressing change. 4. A patient with a history of heart failure requires a general anaesthetic. 5. A dehydrated hypovolaemic patient requires an emergency general anaesthetic. 6. A patient with porphyria comes for an inguinal hernia repair and is requesting a general anaesthetic. 7. A patient requires sedation on the intensive care unit. 8. Anaesthesia in the prehospital environment. What are IV induction drugs? These are drugs that, when given intravenously in an appropriate dose, cause a rapid loss of consciousness. This is often described as occurring within “one arm-brain circulation time” that is simply the time taken for the drug to travel from the site of injection (usually the arm) to the brain, where they have their effect. They are used: • To induce anaesthesia prior to other drugs being given to maintain anaesthesia. • As the sole drug for short procedures. • To maintain anaesthesia for longer procedures by intravenous infusion. • To provide sedation. The concept of intravenous anaesthesia was born in 1932, when Wesse and Schrapff published their report into the use of hexobarbitone, the first rapidly acting intravenous drug. -

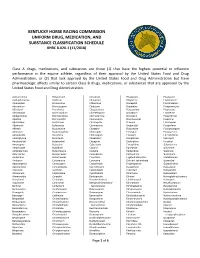

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

The Effectiveness of Ketamine As an Anesthetic for Fish (Rainbow Trout – Oncorhynchus Mykiss)

Research Article Oceanogr Fish Open Access J Volume 13 Issue 1 - January 2021 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Mohammedsaeed Ganjoor DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2021.13.555852 The Effectiveness of Ketamine as an Anesthetic for Fish (Rainbow Trout – Oncorhynchus mykiss) Mohammedsaeed Ganjoor*, Maysam Salahi-ardekani, Sajad Nazari, Javad Mahdavi, Esmail Kazemi and Mohsen Mohammadpour Genetic and Breeding Research Centre for Cold Water Fishes (ShahidMotahary Cold-water Fishes Center), Iranian Fisheries Science Research Institute, Iran Submission: November 03, 2020; Published: January 12, 2021 Corresponding author: Mohammedsaeed Ganjoor, Genetic and Breeding Research Centre for Cold Water Fishes (ShahidMotahary Cold-water Fishes Center), Iranian Fisheries Science Research Institute, Agricultural Research Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Yasuj, IRAN Email: [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract Ketamine was evaluated as water-soluble anesthetics drug for a species of fish, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish (size ~20 - ~240 anesthesiagr.) were exposed duration to (stage1 a 100-ppm to 3) concentrationand recovery duration of Ketamine was recorded.solution (dissolved Also, surveillance in water), was they evaluated were arranged after recovery. in 4 treatments Ketamine wasbased effective on their to weight range (Treatment-1= 22.8±3.4 g; Treatment-2= 51.7±4.4 g; Treatment-3= 69.8±5.2 g and Treatment-4= 243.8±20.7 g). Elapsed time for cause anesthesia in the fish as 100 ppm concentration. 10 fishes of each treatment (%100) were anesthetized and were induced in stageIII-Plane3 of anesthesia within 2-3 min after exposure to anesthetic solution (Treatment-1= 110.3±3.5 seconds; Treatment-2= 140.0±5.9 sec; Treatment-3= 180.0±5.8 sec and Treatment-4= 190.0±5.8 sec). -

Drug Interaction in Anaesthesia a Review

DRUG INTERACTION IN ANAESTHESIA A REVIEW M. M. GHONEIM, M.B., B.CH., F.F.A.R.C.S. = RECENTLY, THE P~OBLE.',~s and hazards associated with the interaction between drugs have received widespread attention. The potential for the interaction has certainly increased in recent years. It has been demonstrated that the average patient will receive eight different drugs during one hospitalization. 1 In many in- stances, one drug may profoundly modify the action of another. In such drug inter- actions the effect of one may be prevented, or its action may be intensified. Though sometimes beneficial, drug interactions are most often recognized when they in- crease mortality or morbidity. They form around 19-22 per cent of causes of adverse drug reactionsd There are a number of good general reviews on drug interac- tions, ~-6 but there are not many which are concerned primarily with the practice of anaesthesia. 7,8 The anaesthetist uses a wide variety of pharmacologically active drugs which may interact with one another or with other drugs the patient is receiving. The multitudes of possible interactions limit the possibility of reviewing each individual drug interaction. This also entails a lot of repetition and would not keep pace with the number of new drugs introduced into the market every month. Our aim is elucidation of the principles and mechanisms involved with examples which are of interest to the anaesthetist. Several mechanisms of interaction are recognized. 1. A direct physical or chemical interaction A familiar example is the neutralization of heparin with protamine. This is an example, also, of a useful drug interaction. -

Plasma Progesterone Concentrations and Ovarian Histology in Prairie Deermice (Peromyscus Maniculatus Bairdii) from Experimental Laboratory Populations

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1973 Plasma Progesterone Concentrations and Ovarian Histology in Prairie Deermice (Peromyscus maniculatus Bairdii) from Experimental Laboratory Populations Barry Douglas Albertson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, and the Endocrinology Commons Recommended Citation Albertson, Barry Douglas, "Plasma Progesterone Concentrations and Ovarian Histology in Prairie Deermice (Peromyscus maniculatus Bairdii) from Experimental Laboratory Populations" (1973). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624808. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7nsc-4k85 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLASMA PPDGESTEPONE CDNCCNTPATIONS AND OVARIAN HISTOLOGY I ’ IN PRAIRIE DEERMICE (PE.RCITYSCUS MANIOJLATUS RAIRDII) FROM EXPERIMENTAL LABORATORY POPULATIONS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Barry Douglas Albertson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts t (XATl-L, P. 0 iLiis X]Author Approved, July, 1973 (S- v u . EricOik L. Bradley, Ph. D. C. RicnardTTferriiah, Ph. ■W)D. fl&itjh (- f- Robert E. u. Black, Phi D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr.