Macintyre-Masters-Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leo Brouwer 251 Roberto Valera 260 Harold Gramatges 263 Argeliers León 272 Carlos Fariñas 277

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE GEOGRAFÍA E HISTORIA Departamento de Arte III (Contemporáneo) TENDENCIAS DE LO NACIONAL EN LA CREACIÓN INSTRUMENTAL CUBANA CONTEMPORÁNEA MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Marta Rodríguez Cuervo Bajo la dirección del Doctor: Emilio Casares Rodicio Madrid, 2002 ISBN: 84-669-1985-6 TESIS DOCTORAL TENDENCIAS DE LO NACIONAL EN LA CREACIÓN INSTRUMENTAL CUBANA CONTEMPORÁNEA (1947 – 1980). MARTA RODRÍGUEZ CUERVO UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID. 2001 – 2002 TESIS DOCTORAL TENDENCIAS DE LO NACIONAL EN LA CREACIÓN INSTRUMENTAL CUBANA CONTEMPORÁNEA (1947 – 1980). MARTA RODRÍGUEZ CUERVO DIRECTOR DE TESIS: DR. EMILIO CASARES RODICIO DEPARTAMENTO ARTE III CONTEMPORÁNEO UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID. MADRID, OCTUBRE DE 2001 TENDENCIAS DE LO NACIONAL EN LA CREACIÓN INSTRUMENTAL CUBANA CONTEMPORÁNEA (1947 – 1980). ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE • Agradecimientos 6 • Prólogo Hacia un enfoque crítico de la obra instrumental cubana contemporánea 8 • Capítulo I De la fuente al intelecto Introducción 18 Elementos fundamentales de comunicación de la música cubana de antecedente hispano-europeo más próximos al músico culto 20 Anexo 29 Elementos fundamentales de comunicación de la música cubana de antecedente africano más próximos al músico culto 32 Elementos fundamentales de comunicación de la contradanza bailable cubana y el danzón más próximos al músico culto 41 Elementos fundamentales de comunicación del complejo del son más próximos al músico culto 49 • Capítulo II Trayecto de lo cubano en un espacio -

Cuba Restaurant | Delivery & Catering Menu

Served with Ceviche Seafd & Fish chips! Aetizers (served with chips) SALMON MIRAMAR 19 Sandwiches EMPANADAS HABANERAS CEVICHE 15 pan-seared salmon fillet, shrimp, SANDWICH CUBANO 10 shrimp, scallops, calamari, avocado, roasted pork, ham, pickles, swiss cheese, 2 for $ 6 / 3 for $9 coconut rice, lobster sauce cilantro, red onion, jalapeño, mustard, pressed cuban bread Choice of: spinach-manchego cheese, sweet peppers, citrus juices beef picadillo or shredded chicken, CAMARONES ENCHILADOS 18 served with tomatillo salsa LOMO ASADO 10 braised shrimp in tomato creole sauce, pork tenderloin, mustard, tomato, avocado onions, peppers, thyme PAPAS RELLENAS 7 Salads LOMO DE CERDO 10 two crispy potato balls with beef picadillo Add chicken 5 | shrimp 7 | skirt steak 8 pork tenderloin, sauteed onions, or cheese served with tomato salsa BACALAO GRATINADO 22 ENSALADA DE CUBA 10 fresh cod fish gratin, aioli & pisto green peppers, tartar saue CHORIZO AL JEREZ 10 mixed green salad, avocado, CALAMARI 15 sautéed spanish chorizo, parsley, cherry tomatoes, red onions, PULPO A LA PLANCHA 22 balsamic vinaigrette crispy calamari, cherry tomatoes, onions, aioli sherry wine reduction and garlic bread grilled octopus, roasted potatoes & aioli PULPO 10 CALAMARES CON TAMARINDO 9 grilled octopus, spanish chorizo, patatas, crispy calamari, sweet plantains, onions, herbs aioli cherry tomato, tamarind vinaigrette TOSTONES RELLENOS 9 Meat green plantains stuffed with shrimp, Soups sofrito sauce BISTEC DE PALOMILLA 22 Chicken grilled-pounded sirloin steak, sautéed SOPA -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

Cuban Music Teaching Unit

Thesis Advisor: Frank Martignetti THE MUSIC AND DANCE OF CUBA: by Melissa Salguero Music Education Program Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Elementary Education in the School of Education University of Bridgeport 2015 © 2015 by Melissa Salguero Salguero 2 Abstract (Table of Contents) This unit is designed for 5th grade students. There are 7 lessons in this unit. Concept areas of rhythm, melody, form, and timbre are used throughout the unit. Skills developed over the 7 lessons are singing, moving, listening, playing instruments, reading/writing music notation, and creating original music. Lesson plans are intended for class periods of approximately 45-50 minutes. Teachers will need to adapt the lessons to fit their school’s resources and the particular needs of their students. This unit focuses on two distinct genres of Cuban music: Son and Danzón. Through a variety of activities students will learn the distinct sound, form, dance, rhythms and instrumentation that help define these two genres. Students will also learn about how historical events have shaped Cuban music. Salguero 3 Table of Contents: Abstract……………………………………………..…………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………….……………………………4 Research…………………………………………..……………………………5 The Cuban Musical Heritage……………….……………………………5 The Discovery of Cuba…….……………………………………………..5 Indigenous Music…...…………………………………………………….6 European Influences……………………………………………….……..6 African Influences………………………………………………………...7 Historical Influences……………………….……………………………..7 -

Documentación Técnica Salsa Cubana SLSC

Documentación técnica Salsa cubana SLSC as raíces de la salsa pueden del nuevo ritmo al que llamaban «son». El remontarse a los antepasados antecedente más directo pues, de la salsa es Lafricanos que fueron enviados al el son cubano que a su vez es una Caribe por los españoles como esclavos. En combinación de distintas influencias África, es muy común encontrar gente europeas y africanas, aunque se nombra tocando música con instrumentos como la frecuentemente, y de manera genérica, conga y la pandereta, instrumentos que como madre de la salsa a la música también son usados comúnmente en la tradicional cubana. Los primeros pasos de música salsa. La confusión que se suele este baile, pues, se desarrollaron en el producir sobre la nomenclatura de la música Casino Deportivo de La Habana y otros afro-caribeña tiene que ver más con salones de baile de la capital cubana a estrategias de mercado que con diferencias finales de los años cincuenta, de ahí el musicales. nombre que tiene en Cuba: casino, aunque originalmente se le llamó el baile del Casino. Se dice que era, en primera instancia, una expresión de baile exclusivo de esclavos que no podían dar pasos muy grandes por culpa de las cadenas que estaban sujetas a sus tobillos para impedir que escapasen. Por ese motivo, cuando los esclavos se reunían por las noches para bailar, sólo les quedaba una solución para hacer que el baile fuera más interesante, y era aumentar la velocidad del ritmo a la vez que hacían los pasos mucho más cortos. Para un esclavo, el baile era como una luz de esperanza en su cruda existencia y, aunque no se sabe si esta referencia histórica es del todo cierta, las letras amargas y las dulces melodías de temas como «El Preso» y «Rebelión» así lo hacen pensar. -

Primera Aproximación a La Habanera En Cataluña*

PRIMERA APROXIMACIÓN A LA HABANERA EN CATALUÑA* Xavier Febrés El ritmo de la habanera fue creado en Cuba en el siglo XIX por compositores cubanos. Se trataba de la adaptación con ritmos de influencia negra de un viejo baile de moda europeo, la country-dance o contradanza inglesa. Acto seguido se popula- rizaría en Cataluña, vehiculado por el caudaloso corriente de la zarzuela, como una de las distintas formas musicales <<deida y vuelta), que se multiplicaban entre Espa- ña y las colonias americanas. Una vez extinguido el protagonismo social de la zarzuela, la práctica de la habanera se desdibujaría en Cuba, mientras mantenía una singular vitalidad en la metrópoli como canto coral o como canción de taberna, hasta convertirse en Catalu- ña en <<unode los fenómenos modernos más notables de tradicionalización),, según apunta el profesor Joaquim Molas en la Historia de la Literatura Catalana1. Es preciso tener en cuenta de entrada que los lenguajes musicales no suelen presentarse en estado puro, con un origen y una evolución delimitados al detalle. Son generalmente fruto de trayectorias complejas, de entrecruzamientos de influencias, de mezclas no siempre claramente definibles. La primera música europea de salón llegada a las colonias americanas estaba formada por branles francesas, gavotas, valses, gallardas, pavanas, zarabandas, chaconas. La segunda tanda fue la del minueto, la bourré, la giga, el fandango y la famosa contradanza. La <<criollización),de la contradanza operada en Cuba por mú- * Traducción al castellano de la ponencia presentada el 18 de octubre de 1990 en las IV Jornadas Catalano-Americanas, organizadas en Barcelona por la Comissió Catalunya-América92. -

Son Patin Linear Style Salsa, Basics Isolation (On1) Elements of Rumba

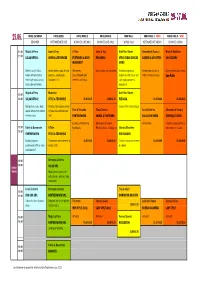

25.06. HOTEL KATARINA HOTEL EDEN HOTEL PARK 1 HOTEL PARK 2 MMC HALL ADRIS HALL 1 - NEW! ADRIS HALL 2 - NEW! BEGINNER INTERMMEDIATE LINE ADVANCED LINE (ON1) ADVANCED LINE (ON2) WORLD SALA INTERMMEDIATE CUBAN ADVANCED CUBAN 11:00 Matjaž & Petra Jorjet & Troy U-Tribe Jorjet & Troy Ariel Rios Robert Alexander & Yunaisy Mario & Madeline 11:50 SALSA INTRO 1 SHINES & TECHNIQUE FOOTWORK & BODY PACHANGA AFRO-CUBAN DANCES DANZON & SON INTRO SON CUBANO MOVEMENT INTRO What is salsa? Salsa Simple shines, body & hand Afro shines. Basics steps and variations.History background, Introductory classes in Clave, rhythm, basic steps history. Introduction in postures, simple body Salsa footwork with importance for dance and Cuban national dances. Son Patin linear style salsa, basics isolation (On1) elements of rumba. style, body posture & steps, demonstration. movement Matjaž & Petra Mambata Ariel Rios Robert 12:00 12:50 SALSA INTRO 2 STYLE & TECHNIQUE 11.00-12.20 11.00-12.20 ELEGGUA 11.00-12.20 11.00-12.20 Bod posture, cross body Fluidity, style & body control Dance of the orisha Elegua lead & simple turn pattern in linear salsa partnerwork Fran & Veronika Tito & Tamara Israel Gutierrez Alexander & Yunaisy in linear salsa (On1) PARTNERWORK SHINES & FOOTWORK SALSA CON TIMBA TECHNIQUE WORK Leading and following Working on technique. Partnerwork Footwork, body posture & 13:00 Fabris & Rosemarie U-Tribe techniques PR style shines - building up Mario & Madeline movements in Casino 13:50 PARTNERWORK STYLE & TECHNIQUE from simple to advanced SON CUBANO Building up your Partnerwork with elements of 12.40-14.00 12.40-14.00 Tornillos variations for men 12.40-14.00 12.40-14.00 partnerwork. -

Redalyc."Somos Cubanos!"

Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música E-ISSN: 1697-0101 [email protected] Sociedad de Etnomusicología España Froelicher, Patrick "Somos Cubanos!" - timba cubana and the construction of national identity in Cuban popular music Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música, núm. 9, diciembre, 2005, p. 0 Sociedad de Etnomusicología Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82200903 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Somos Cubanos! Revista Transcultural de Música Transcultural Music Review #9 (2005) ISSN:1697-0101 “Somos Cubanos!“ – timba cubana and the construction of national identity in Cuban popular music Patrick Froelicher Abstract The complex processes that led to the emergence of salsa as an expression of a “Latin” identity for Spanish-speaking people in New York City constitute the background before which the Cuban timba discourse has to be seen. Timba, I argue, is the consequent continuation of the Cuban “anti-salsa-discourse” from the 1980s, which regarded salsa basically as a commercial label for Cuban music played by non-Cuban musicians. I interpret timba as an attempt by Cuban musicians to distinguish themselves from the international Salsa scene. This distinction is aspired by regular references to the contemporary changes in Cuban society after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Thus, the timba is a “child” of the socialist Cuban music landscape as well as a product of the rapidly changing Cuban society of the 1990s. -

Conexión Cubana Currently One the Best of Son Cubano Groups Cuba

Conexión Cubana Currently one the best of Son Cubano groups Cuba has to offer! They have been touring worldwide for many years and they are currently one of the most desirable aspiring son cubano ensembles. In Cuba, everyone knows them: but “Conexión Cubana” is loved by top-class Cuban musicians too, with its musical joy and wide variety of ideas. It’s that exuberant vivacity coupled with son cubano that makes this band so successful. Head of the band Nicolás Sirgado is one of the most popular composers and arrangers from Habana. Countless albums – and numerous TV productions – bear his name. Now, with his own project “Conexión Cubana” he is both leader and bass player. After five European concert tours together with Luis Frank under the name of “Soneros de Verdad”, he is finally joined by legendary singer William Borrego Rodriguez. In the past he worked with great artists like Pancho Amat, Silvio Rodriguez, Pablo Milanes, Diego “El Cigalo”, Barbarito Torres or Andy Montañez, and he is one of Cuba’s truly great singers. Cd’s (former Soneros De Verdad) 2001 “a Buena Vista” 2003 “Present Rubalcaba” 2004 “El Run Run de los Soneros” 2004 “Present Pio Leiva” 2007 “Rubalcaba Pio Leiva y Luis Frank” 2010 “Present Musica Cubana” 2012 “2012″ 2013 “Present Rubalcaba y Cesar Pedroso” 2013 “Present Mayito Rivera” 2013 “Un Dos Tres Soneros” 2014 “Amarrate” 2014 “Present Lazaro” 2015 “Viva Cuba Libre!” 2019 – new CD is comming up! Conexion Cubana Info Style: Latin, Buena Vista, World, Jazz Origin: Cuba Based in: Cuba Travel party: 9 (7 musicians & 2 crew) Line-up: William Borrego Rodriguez/ Vocal, Trombone Lázaro Dilout / Trumpet, Vocal Nicolás Sirgado / Bass, Vocal Sergio Veranes / Piano, Vocal Querol Aldana / Guitar / Tres, Vocal Vivo Barrera / Percussion Fabián Sirgado / Congas, Vocal . -

Join Us for a Once in a Lifetime Experience in Cuba!

Join us for a once in a lifetime experience in Cuba! Study Abroad May 2016: Havana, Cuba MUEN 1151 Chamber Singers: Cuban Singing, Dancing and Drumming Instructor: Dr. Mark Marotto (LSC-Montgomery) Learn how Cuban music brings together African and Hispanic traditions of singing, dance and drumming. During your time in Havana you will experience Cuba’s rich musical heritage first-hand, learning the style, instruments, and performance practices specific to Cuban music. You will share performances with Cuban musicians and attend master classes taught by Cuban music and dance teachers. Through conversations and people-to-people exchange, you will gain a deeper understanding of the daily lives of the Cuban people and the critically important role of the arts in their society. Trip Outline: May 16-19: Preparation at LSC-Montgomery Campus (rehearsals and discussions to prepare for the trip) May 19-26: Experience Cuba! (exchanges, performances, master classes, lessons, rehearsals, conversations, guided exploration) May 27: Home Concert at LSC-Montgomery Campus (share what you’ve learned with friends and family) Lone Star College has partnered with MetaMovements Cultural Connections to create a custom travel experience to Cuba. Who We Are & What We Do: MetaMovements is an entrepreneurial Artist Collective dedicated to using the arts as a tool for positive transformation. In addition to teaching, performing, and leading community arts projects, we also host cultural tours that bring people together for unique, uplifting experiences in Cuba, the U.S., and other locations. Our director has deep personal ties to Cuba, and for over 20 years has consulted on authentic exchanges and cultural programs between Cuban & U.S. -

The Dynamics of Salsiology in Comtemporary Germany

THE DYNAMICS OF SALSIOLOGY IN CONTEMPORARY GERMANY: RECONSTRUCTING GERMAN CULTURAL IDENTITY THROUGH SALSA MUSIC AND DANCE Eddy Magaliel Enríquez Arana A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2007 Committee: Dr. Christina Guenther, Advisor Dr. Francisco Cabanillas, Advisor Dr. Valeria Grinberg Pla Dr. Geoffrey Howes © 2006 Eddy M. Enríquez Arana All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Christina Guenther, Advisor Dr. Francisco Cabanillas, Advisor This thesis explores the significance of the consumption of salsa music and dance in the Federal Republic of Germany and its impact on the construction and reconstruction of German and Latin American cultural identity. The discipline of cultural studies has much to learn from the Latin American presence in and their contributions to the establishment of the salsa institution in the Federal Republic. The thesis discusses the level of German involvement in the creation of a transnational music and dance culture traditionally associated with the Spanish-speaking world exclusively. iv To all my friends, peers and family who support me in my love for the German language and salsa music. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Ernesto Delgado of the Romance Languages Department for guiding and encouraging me in the conceptualization of the topic of this writing project; to Dr. Christina Guenther of the German section whose untiring and superb academic counseling oriented not only my scholarly development but also my skills as a writer, and instilled in me confidence and drive to excel in the study of cultures and languages; to Dr. -

Guía Didáctica Para El Acompañamiento Del Son Cubano En La Guitarra

Guía didáctica para el acompañamiento del son cubano en la guitarra Monografía presentada para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Música Salomón Ochoa Gracia Código: 2014175026 Asesor: Marius Díaz Moreno Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Departamento De Educación Musical Facultad de Bellas Artes Licenciatura En Música Bogotá D. C. 2020 Resumen El presente trabajo toma como punto de partida el estudio del son cubano, centrándose en los elementos caracterizadores de esta música, especialmente los que conciernen a la guitarra. Sin embargo, también son abordadas algunas visiones musicológicas relevantes dentro del género así como el componente histórico. Por otra parte se realiza el análisis de piezas musicales interpretadas en guitarra las cuales son presentadas junto a su respectiva transcripción. El trabajo concluye con la presentación de una guía didáctica del son cubano aplicada a la guitarra, la cual aborda todos los elementos expuestos durante el desarrollo de la monografía. Abstract This work takes as a starting point the study of the Cuban son, focusing on the characteristic elements of this music, especially those that concern the guitar. However, some relevant musicological visions within the genre are also addressed, as well as the historical component. On the other hand, the analysis of musical pieces performed on guitar is performed, which are presented together with their respective transcription. The work concludes with the presentation of a didactic guide of the Cuban son applied to the guitar, which addresses all the elements exposed during the development of the monograph. Tabla de Contenido INTRODUCCIÓN .............................................................................................................. 1 1. ASPECTOS GENERALES DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN 4 1.1 Descripción del problema ............................................................................................