Hermes Scythicus Or the Radical Affinities of the Greek and Latin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Succeeding Succession: Cosmic and Earthly Succession B.C.-17 A.D

Publication of this volume has been made possiblej REPEAT PERFORMANCES in partj through the generous support and enduring vision of WARREN G. MOON. Ovidian Repetition and the Metamorphoses Edited by LAUREL FULKERSON and TIM STOVER THE UNIVE RSITY OF WI S CON SIN PRE SS The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059 Contents uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden London WC2E SLU, United Kingdom eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2016 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Preface Allrights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical vii articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, transmitted in any format or by any means-digital, electronic, Introduction: Echoes of the Past 3 mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise-or conveyed via the LAUREL FULKERSON AND TIM STOVER Internetor a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rightsinquiries should be directed to rights@>uwpress.wisc.edu. 1 Nothing like the Sun: Repetition and Representation in Ovid's Phaethon Narrative 26 Printed in the United States of America ANDREW FELDHERR This book may be available in a digital edition. 2 Repeat after Me: The Loves ofVenus and Mars in Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ars amatoria 2 and Metamorphoses 4 47 BARBARA WElDEN BOYD Names: Fulkerson, Laurel, 1972- editor. 1 Stover, Tim, editor. Title: Repeat performances : Ovidian repetition and the Metamorphoses / 3 Ovid's Cycnus and Homer's Achilles Heel edited by Laurel Fulkerson and Tim Stover. PETER HESLIN Other titles: Wisconsin studies in classics. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Ritual Cleaning-Up of the City: from the Lupercalia to the Argei*

RITUAL CLEANING-UP OF THE CITY: FROM THE LUPERCALIA TO THE ARGEI* This paper is not an analysis of the fine aspects of ritual, myth and ety- mology. I do not intend to guess the exact meaning of Luperci and Argei, or why the former sacrificed a dog and the latter were bound hand and foot. What I want to examine is the role of the festivals of the Lupercalia and the Argei in the functioning of the Roman community. The best-informed among ancient writers were convinced that these were purification cere- monies. I assume that the ancients knew what they were talking about and propose, first, to establish the nature of the ritual cleanliness of the city, and second, see by what techniques the two festivals achieved that goal. What, in the perception of the Romans themselves, normally made their city unclean? What were the ordinary, repetitive sources of pollution in pre-Imperial Rome, before the concept of the cura Urbis was refined? The answer to this is provided by taboos and restrictions on certain sub- stances, and also certain activities, in the City. First, there is a rule from the Twelve Tables with Cicero’s curiously anachronistic comment: «hominem mortuum», inquit lex in duodecim, «in urbe ne sepelito neve urito», credo vel propter ignis periculum (De leg. II 58). Secondly, we have the edict of the praetor L. Sentius C.f., known from three inscrip- tions dating from the beginning of the first century BC1: L. Sentius C. f. pr(aetor) de sen(atus) sent(entia) loca terminanda coer(avit). -

Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? 2019

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Tomáš Lukáč Deadpool – Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Tomáš Lukáč 2 I would like to thank everyone who helped to bring this thesis to life, mainly to my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his patience, as well as to my parents, whose patience exceeded all reasonable expectations. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………...6 Tricksters across Cultures and How to Find Them ........................................................... 8 Loki and His Role in Norse Mythology .......................................................................... 21 Character of Deadpool .................................................................................................... 34 Comic Book History ................................................................................................... 34 History of the Character .............................................................................................. 35 Comic Book Deadpool ................................................................................................ 36 Films ............................................................................................................................ 43 Deadpool (2016) -

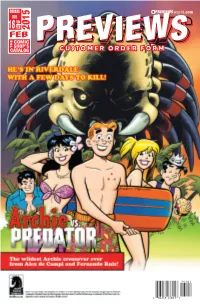

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

"A Mighty Maze! Without a Plan" Cosmological

"A MIGHTY MAZE! BUT NOT WITHOUT A PLAN" COSMOLOGICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF THE LABYRINTH Vahtang Hark Shervashidze, Master of Arts <Hons. l, Science and Technology Studies, 1989 A.H.D.G. Expa.tia.te free o'er all this scene of Man; A mighty maze! but not without a plan; A viId, where weeds and flowers promiscuous shoot j Or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit. Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, 1,5-8. I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my know ledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Vahtang Mark Shervashidze 1 ABSTRACT The history of the labyrinth in Western thought is intimately connected with the development of Christianity and the philosophical movements associated with it. Roughly speaking, the labyrinth has passed through three periods of development. First, there were the Minoan and Greek sources of the Theseus cycle, which are the foundation of 1abyrinth-1 ore. The Greeks also provided the analogical structure which allowed the labyrinth to expand its repertoire of metaphor beyond mythology into literature. Secondly, perhaps due to the renascence of classical literature in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the labyrinth enjoyed some popularity in France and Italy. Here we must distinguish between purely conceptual, literary labyrinths and the artifactual examples which dot cathedral and church floors across the lie de France and Italy. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA. -

Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and Was Thought of As the Personification of Cyclic Law, the Causal Power of Expansion, and the Angel of Miracles

Ζεύς The Angel of Cycles and Solutions will help us get back on track. In the old schools this angel was known as Jupiter (Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and was thought of as the personification of cyclic law, the Causal Power of expansion, and the angel of miracles. Price, John Randolph (2010-11-24). Angels Within Us: A Spiritual Guide to the Twenty-Two Angels That Govern Our Everyday Lives (p. 151). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Zeus 1 Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice [1] The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680 Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak Consort Hera and various others Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter Children Aeacus, Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Dardanus, Dionysus, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces [2] Roman equivalent Jupiter Zeus (Ancient Greek: Ζεύς, Zeús; Modern Greek: Δίας, Días; English pronunciation /ˈzjuːs/[3] or /ˈzuːs/) is the "Father of Gods and men" (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε, patḕr andrōn te theōn te)[4] who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.[5] He is known for his erotic escapades. -

Apoikia in the Black Sea: the History of Heraclea Pontica, Sinope, and Tios in the Archaic and Classical Periods

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2018 Apoikia in the Black Sea: The History of Heraclea Pontica, Sinope, and Tios in the Archaic and Classical Periods Austin M. Wojkiewicz University of Central Florida Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wojkiewicz, Austin M., "Apoikia in the Black Sea: The History of Heraclea Pontica, Sinope, and Tios in the Archaic and Classical Periods" (2018). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/324 APOIKIA IN THE BLACK SEA: THE HISTORY OF HERACLEA PONTICA, SINOPE, AND TIOS IN THE ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL PERIODS by AUSTIN M. WOJKIEWICZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts & Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term, 2018 Thesis Chair: Edward Dandrow ABSTRACT This study examines the influence of local and dominant Network Systems on the socio- economic development of the southern Black Sea colonies: Heraclea Pontica, Sinope, and Tios during the Archaic and Classical Period. I argue that archeological and literary evidence indicate that local (populations such as the Mariandynoi, Syrians, Caucones, Paphlagonians, and Tibarenians) and dominant external (including: Miletus, Megara/Boeotia, Athens, and Persia) socio-economic Network systems developed and shaped these three colonies, and helped explain their role in the overarching Black Sea Network.