Aspects of the Traditional Gambling Game Known As Sho in Modern Lhasa — Religious and Gendered Worldviews Infusing the Tibetan Dice Game — 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

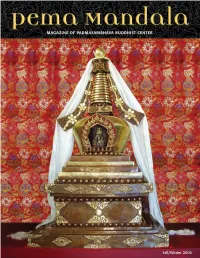

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong

Pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong The Written Tradition and Contemporary Practices among Amdo Tibetans ,#-7--a};-1 Zhuoma ( |) Thesis Submitted for the Degree of M. Phil in Tibetan Studies Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo Spring 2008 1 Summary This thesis focuses on pilgrimage (gnas skor) to Drakar Dreldzong, a Buddhist holy mountain (gnas ri) in a remote area of Amdo, Tibet, in the present day Qinghai Province in the western part of China. The mountain had long been a solitude hermitage and still is a popular pilgrimage site for Tibetan lamas and nearby laymen. Pilgrimage to holy mountains was, and still is, significant for the religious, cultural and literary life of Tibet, and even for today’s economic climate in Tibet. This thesis presents the traditional perceptions of the site reflected both in written texts, namely pilgrimage guides (gnas bshad), and in the contemporary practices of pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong. It specifically talks about an early pilgrimage guide (Guide A) written by a tantric practitioner in the early 17th century, and newly developed guides (Guides B, C and D), based on the 17th century one, edited and composed by contemporary Tibetan lay intellectuals and monks from Dreldzong Monastery. This monastery, which follows the Gelukba tradition, was established in 1923 at the foot of the mountain. The section about the early guide mainly introduces the historical framework of pilgrimage guides and provides an impression of the situation of the mountain in from the 17th to the 21st century. In particular, it translates the text and gives comments and analysis on the content. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

A Sorrowful Song to Palden Lhamo Kün-Kyab Tro

A SORROWFUL SONG TO PALDEN LHAMO KÜN-KYAB TRO- DREL A PRAISE BY HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA Expanse of great bliss, all-pervading, free from elaborations, with either angry or desirous forms related to those to be subdued. You overpower the whole apparent world, samsara and nirvana. Sole mother, lady victorious over the three worlds, please pay attention here and now! During numberless eons, By relying upon and accustoming yourself to the extensive conduct of the bodhisattvas, which others find difficult to follow, you obtained the power of the sublime vajra enlightenment; loving mother, you watch and don’t miss the [right] time. The winds of conceptuality dissolve into space. Vajra-dance of the mind that produces all the animate and inanimate world, as the sole friend yielding the pleasures of existence and peace, having conquered them all, you are well praised as the triumphant mother. By heroically guarding the Dharma and dharma- holders, with the four types of actions, flashing like lightning, You soar up openly, like the full moon in the midst of a garland of powerful Dharma protectors. When from the troublesome nature of this most degenerated time The hosts of evil omens — desire, anger, ignorance — increasingly rise, even then your power is unimpeded, sharp, swift and limitless. How wonderful! Longingly remembering you, O Goddess, from my heart, I confess my broken vows and satisfy all your pleasures. Having enthroned you as the supreme protector, greatest among the great, accomplish your appointed tasks with unflinching energy! Fierce protecting deities and your retinues who, in accordance with the instructions of the supreme siddha, the lotus-born vajra, and by the power of karma and prayers, have a close connection as guardians of Tibet, heighten your majesty and increase your powers! All beings in the country of Tibet, although destroyed by the enemy and tormented by unbearable suffering, abide in the constant hope of glorious freedom. -

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present OXFORD

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present Wolfson College 6 t h -7 t h May, 2016 OXFORD Welcome I am pleased to welcome you to the first International Conference on Spiti, which is being held at the Leonard Wolfson Auditorium on May 6 th and 7 th , 2016. The Spiti Valley is a remote Buddhist enclave in the Indian Himalayas. It is situated on the borders of the Tibetan world with which it shares strong cultural and historical ties. Often under-represented on both domestic and international levels, scholarly research on this subject – all disciplines taken together – has significantly increased over the past decade. The conference aims at bringing together researchers currently engaged in a dialogue with past and present issues pertaining to Spitian culture and society in all its aspects. It is designed to encourage interdisciplinary exchanges in order to explore new avenues and pave the way for future research. There are seven different panels that address the theme of this year’s conference, The Spiti Valley : Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present , from a variety of different disciplinary perspectives including, archaeology, history, linguistics, anthropology, architecture, and art conservation. I look forward to the exchange of ideas and intellectual debates that will develop over these two days. On this year’s edition, we are very pleased to have Professor Deborah Klimburg-Salter from the universities of Vienna and Harvard as our keynote speaker. Professor Klimburg-Salter will give us a keynote lecture entitled Through the black light - new technology opens a window on the 10th century . -

The Dalai Lama

THE INSTITUTION OF THE DALAI LAMA 1 THE DALAI LAMAS 1st Dalai Lama: Gendun Drub 8th Dalai Lama: Jampel Gyatso b. 1391 – d. 1474 b. 1758 – d. 1804 Enthroned: 1762 f. Gonpo Dorje – m. Jomo Namkyi f. Sonam Dargye - m. Phuntsok Wangmo Birth Place: Sakya, Tsang, Tibet Birth Place: Lhari Gang, Tsang 2nd Dalai Lama: Gendun Gyatso 9th Dalai Lama: Lungtok Gyatso b. 1476 – d. 1542 b. 1805 – d. 1815 Enthroned: 1487 Enthroned: 1810 f. Kunga Gyaltsen - m. Kunga Palmo f. Tenzin Choekyong Birth Place: Tsang Tanak, Tibet m. Dhondup Dolma Birth Place: Dan Chokhor, Kham 3rd Dalai Lama: Sonam Gyatso b. 1543 – d. 1588 10th Dalai Lama: Tsultrim Gyatso Enthroned: 1546 b. 1816 – d. 1837 f. Namgyal Drakpa – m. Pelzom Bhuti Enthroned: 1822 Birth Place: Tolung, Central Tibet f. Lobsang Drakpa – m. Namgyal Bhuti Birth Place: Lithang, Kham 4th Dalai Lama: Yonten Gyatso b. 1589 – d. 1617 11th Dalai Lama: Khedrub Gyatso Enthroned: 1601 b. 1838– d. 1855 f. Sumbur Secen Cugukur Enthroned 1842 m. Bighcogh Bikiji f. Tseten Dhondup – m. Yungdrung Bhuti Birth Place: Mongolia Birth Place: Gathar, Kham 5th Dalai Lama: 12th Dalai Lama: Trinley Gyatso Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso b. 1856 – d. 1875 b. 1617 – d. 1682 Enthroned: 1860 Enthroned: 1638 f. Phuntsok Tsewang – m. Tsering Yudon f. Dudul Rapten – m. Kunga Lhadze Birth Place: Lhoka Birth Place: Lhoka, Central Tibet 13th Dalai Lama: Thupten Gyatso 6th Dalai Lama: Tseyang Gyatso b. 1876 – d. 1933 b. 1683 – d. 1706 Enthroned: 1879 Enthroned: 1697 f. Kunga Rinchen – m. Lobsang Dolma f. Tashi Tenzin – m. Tsewang Lhamo Birth Place: Langdun, Central Tibet Birth Place: Mon Tawang, India 14th Dalai Lama: Tenzin Gyatso 7th Dalai Lama: Kalsang Gyatso b. -

The Three Sisters in the Ge-Sar Epic

THE THREE-SISTERS IN THE GE-SAR EPIC -Siegbert Hummel In its Mongolian version, as published by I. J. Schmidt in German translation 1, . as well as in the Kalmuk fragments which were made known as early as 1804/0 S by Benjamin Bergmann2 the Ge-sar saga repeatedly mentions three sisters who prompt his actions during his life on earth, who urge him on or rebuke him 3 Not only Ge-sar, but also the giant with whom he enters into combat and finally kills, has three maidens as sisters, and, as can be understood from the action, they are a kind of goddesses of fate who dwell in trees which are to be regarded as the seat ofthe vital-pow~r (Tib.: bla) of the monster, i.e. as socalled bla-gnas or bla-shing. Consequently the giant is brought to the point of ruin by the killing of the maidens and the destruction ot the trees4. \ The three sisters are in all respects to be distinguished from the well-known genii of man who are born together with him and who appear in' the Tibetan judgment of the dead where the good genius, a lha (Skt.: deva), enumerates the good deeds of the deceased by means of white pebbles, while the evil one, a demon (Tib.:' dre), counts the evil actions with black pebb1es S. Nor are the three sisters to be identified wilhthe personal guardian deities of the Tibetans, the 'go-ba'i-1ha, with whom they have certain traiits in common. The group of 'go ha'i -lha normally has five members. -

1 Revival of Indigenous Practices and Identity in 21St Century Inner Asia

Revival of Indigenous Practices and Identity in 21st Century Inner Asia Amalia H. Rubin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington 2015 Committee: Sara Curran Wolfram Latsch Program Authorize to Offer Degree: International Studies 1 © Copyright 2015 Amalia H. Rubin 2 University of Washington Abstract Revival of Indigenous Practices and Identity in 21st Century Inner Asia Amalia H Rubin Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sara Curran, Ph.D. Associate Professor of International Studies and Public Affairs Scholars and observers have noticed an emerging pattern in the world wherein communities that have suffered a period of cultural and religious repression, when faced with freedom, experience a sudden surge in certain aspects of cultural practice. The most interesting of these are the so-called “involuntary” practices, such as trance, and spontaneous spirit possession. Why is it that, in the period of freedom when many missionary groups, traditional and foreign, arrive to make claims on souls, we see a disproportionate resurgence of indigenous, non-missionary practices? And why especially those practices in which the practitioner has no conscious control? I aim to explore the significance of the revival of indigenous practices, both voluntary and involuntary, their connection to the assertion of cultural identity after a period of intense repression, and their significance to the formation of development and research approaches in such regions. In this paper, I will look at two examples of cultural revival: 3 Böö Mörgöl (commonly referred to as “Mongolian Shamanism” or “Tengerism”) in Ulaanbaatar, Republic of Mongolia, and the revival of Gesar cultural and religious practices in Kham, Tibet, primarily in Yushu, Qinghai province, China. -

Speech Given at Naumann Foundation Hamburg

Friedrich-Naumann-Foundation Hamburg, on March 26th 1999 Dalai Lama Dorje Shugden by Helmut Gassner Letzehof 6800 Feldkirch, Austria EMAIL: [email protected] 1 How a runaway Austrian gets to meet the Dalai Lama is a story most of us probably know from the wonderful account of "Seven Years in Tibet." But how a run-of-the-mill Austrian like myself got to meet the Dalai Lama is no doubt a tale of considerable less fascination. While I was studying electrical engineering at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich, I was introduced to a lady who had known Tibetan Lamas in India in the 1960's. She spoke of Lama Thubten Yeshe and Zopa Rinpoche time and again as well as of their teacher, Venerable Geshe Rabten, who was able to explain Buddhism with unequalled clarity and forcefulness and who really understood Westerners and their ideas. After Geshe Rabten escaped from Tibet, the Dalai Lama chose him and Lati Rinpoche from among a select group of candidates to become one of his advisers on philosophical issues. Upon the Dalai Lama's express wish, Geshe came to Switzerland as Abbot of Rikon Monastery, near Winterthur. After I graduated from the Institute of Technology, I moved to Rikon to learn Tibetan and to study Buddhist philosophy, debate and meditation under Geshe's guidance. In 1978, Geshe Rabten was invited by a group of Geshe Zopa, a Tibetan who teaches at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and to my great joy, I was allowed to accompany Geshe. At that conference there was another most impressive Lama from India, Zong Rinpoche, also giving teachings and initiations. -

Speech Delivered by His Holiness 14 Dalai Lama to the Second Gelug

Speech Delivered by His Holiness 14th Dalai Lama to the Second Gelug Conference (Dharamsala, June 12th 2000) We meet here today with Ganden Tri Rinpoche, the representative of Jamgön Gyelwa (Lama Tsong Khapa), chiefly gracing us with his presence. The abbots representing the three seats of Sera, Drepung, Ganden, as well as those of Tashi Lhunpo, Gyutö and Gyumei tantric colleges have joined us; as have abbots and former abbots who are here on behalf of the various other Gelug monasteries. It seems though that the Manali representative has not been able to join us though (laughter)1. Anyway as well as all of these guests I also have been able to attend this Gelug conference. The organisation of these international Gelug conferences and the general concern for the maintenance and promotion of the teaching is admirable. I would like to thank all of you for your concern and for having put in such hard work. Given the significance of this event, I would like to encourage everyone, for the space of these few days, to dispense with ostentatious posing and the empty formalities of ceremony. Let’s try to get to the heart of the matter. We have now gained quite a bit of experience. So let us utilise that to focus on what problems we face and give some thought to how we can improve things. Our consideration of these matters should be careful. I have high hopes that this will prove to be an open forum for the discussion of the important issues and will generally prove to be a success. -

The Tibetan Situation Today

The Tibetan Situation Today Surprising Hidden News Letter to the Dalai Lama of Tibet 12th April 2008 To the Dalai Lama of Tibet, We the Western Shugden Society ask you to accomplish four things: 1. To give freedom to practice Dorje Shugden to whoever wishes to rely upon this Deity. 2. To stop completely the discrimination between Shugden people and non-Shugden practitioners. 3. To allow all Shugden monks and nuns who have been expelled from their monasteries and nunneries to return to their monasteries and nun neries where they should receive the same material and spiritual rights as the non-Shugden practitioners. 4. That you tell in writing to the Tibetan community throughout the world that they should practically apply the above three points. Do you accept these four points? We require your answer by the 22 April 2008, signed and delivered by registered post to: Western Shugden Society c/o Dorje Shugden Devotees Society, House No 10, Old Tibetan Camp, Majnu Ka Tilla, Delhi-4 With a copy of your letter sent to the following email address: [email protected] Letter to the Dalai Lama of Tibet If we do not receive your answer by 22 April 2008, we will regard that you have not accepted. The Western Shugden Society cc Kashag Secretary, Parliamentary Secretary (Tibetan Parliament-in-exile), Dept. of Religion & Culture (Central Tibetan Administration), Assistant Com missioner (Representative for Tibetans) Letter to Sera Lachi, Sera Jey and Sera Mey April 9, 2008 To Sera Lachi, Sera Jey, and Sera Mey, We, the Western Shugden Society, are writing this letter to you concerning the six monks from Pomra Khangtsen that you have expelled on April 8th, 2008 based on wrong and false reasons. -

Reading the History of a Tibetan Mahakala Painting: the Nyingma Chod Mandala of Legs Ldan Nagpo Aghora in the Roy Al Ontario Museum

READING THE HISTORY OF A TIBETAN MAHAKALA PAINTING: THE NYINGMA CHOD MANDALA OF LEGS LDAN NAGPO AGHORA IN THE ROY AL ONTARIO MUSEUM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Aoife Richardson, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. John C. Huntington edby Dr. Susan Huntington dvisor Graduate Program in History of Art ABSTRACT This thesis presents a detailed study of a large Tibetan painting in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) that was collected in 1921 by an Irish fur trader named George Crofts. The painting represents a mandala, a Buddhist meditational diagram, centered on a fierce protector, or dharmapala, known as Mahakala or “Great Black Time” in Sanskrit. The more specific Tibetan form depicted, called Legs Idan Nagpo Aghora, or the “Excellent Black One who is Not Terrible,” is ironically named since the deity is himself very wrathful, as indicated by his bared fangs, bulging red eyes, and flaming hair. His surrounding mandala includes over 100 subsidiary figures, many of whom are indeed as terrifying in appearance as the central figure. There are three primary parts to this study. First, I discuss how the painting came to be in the museum, including the roles played by George Croft s, the collector and Charles Trick Currelly, the museum’s director, and the historical, political, and economic factors that brought about the ROM Himalayan collection. Through this historical focus, it can be seen that the painting is in fact part of a fascinating museological story, revealing details of the formation of the museum’s Asian collections during the tumultuous early Republican era in China.