Decolonizing Desires and Unsettling Musicology: a Settler's Personal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017 JUNO FAN CHOICE (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Belly Roc Nation*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Hedley Universal Justin Bieber Def Jam*Universal Ruth B Columbia*Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Wild Things Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal One Dance ft. Wizkid & Kyla Drake Cash Money*Universal Treat You Better Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Spirits The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal Starboy ft. Daft Punk The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY IDLA ASSOCIATED LABEL DISTRIBUTION) Dangerous Woman Ariana Grande Republic*Universal A Head Full of Dreams Coldplay Parlophone*Warner Made in the A.M. One Direction Sony ANTI Rihanna Westbury Road*Universal This is Acting Sia RCA*Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Encore un Soir Céline Dion Sony Views Drake Cash Money*Universal You Want It Darker Leonard Cohen Sony Illuminate Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Starboy The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal ARTIST OF THE YEAR Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Leonard Cohen Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR Arkells Arkells*Universal Billy Talent Warner Tegan and Sara Warner Bros. -

Canadian Journal of Archaeology Journal Canadien D'archéologie

Canadian Journal of Archaeology Journal Canadien d’Archéologie SPECIAL ISSUE: UNSETTLING ARCHAEOLOGY Guest Edited by Lisa Hodgetts and Laura Kelvin Volume 44, 2020 • Issue 1 Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie Editor-in-Chief/Rédacteur en chef Associate Editor/Rédacteur adjoint John Creese Frédéric Dussault Department of Sociology and Anthropology [[email protected]] North Dakota State University Copy Editor/Réviseure Dept. 2350, PO Box 6050, Aleksa Alaica Fargo, ND, USA 58108-6050 Department of Anthropology, Ph: (701) 231-7434 University of Toronto [[email protected]] [[email protected]] Editorial Assistant/Adjointe à la rédaction Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus Cheryl Takahashi Katherine Patton Takahashi Design Anthropology Building, University of Toronto 4358 Island Hwy. S. 19 Russell Street, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2 Courtenay, BC V9N 9R9 Ph: (416) 946-3589 Ph: (250) 650-3766; [[email protected]] [[email protected]] EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD / COMITÉ CONSULTATIF DE RÉDACTION • Arctic—Peter Dawson, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary • Subarctic—Scott Hamilton, Department of Anthropology, Lakehead University • Pacific Northwest—Alan McMillan, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University • Prairie Region—Jack Brink, Royal Alberta Museum, Edmonton • Ontario—Neal Ferris, Department of Anthropology, University of Western Ontario • Quebec—André Costopoulos, Department of Anthropology, McGill University • Atlantic—Michael -

2017 JUNO GALA Dinner & Award Winners

2017 JUNO GALA Dinner & Award Winners April 1, 2017 SINGLE OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY LIVE NATION CANADA) Hotel Paranoia Jazz Cartier Universal Spirits The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal DANCE RECORDING OF THE YEAR INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY IDLA Off the Ground ft. Shae Jacobs Bit Funk PhysiCal Presents*Universal ASSOCIATED LABEL DISTRIBUTION) A Head Full of DreaMs Coldplay Parlophone*Warner R&B/SOUL RECORDING OF THE YEAR Starboy The Weeknd The WeeknD XO*Universal ARTIST OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY TD) Leonard Cohen Sony REGGAE RECORDING OF THE YEAR Siren Exco Levi Reggaeville*Independent BREAKTHROUGH GROUP OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY FACTOR, THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, CANADA’S PRIVATE RADIO BROADCASTERS, INDIGENOUS MUSIC ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY AND RADIO STARMAKER FUND) ABORIGINAL PEOPLES TELEVISION NETWORK) The Dirty Nil Dine Alone*Universal Tiny Hands Quantum Tangle Coax*Independent ADULT ALTERNATIVE ALBUM OF THE YEAR CONTEMPORARY ROOTS ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY Secret Path Gord Downie Arts & Crafts*Universal NATIONAL ARTS CENTRE) Earthly Days William Prince InDepenDent ALTERNATIVE ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY LONG & MCQUADE) TRADITIONAL ROOTS ALBUM OF THE YEAR Touch July Talk Sleepless*Universal Secret Victory The East Pointers The East Pointers*Fontana North ROCK ALBUM OF THE YEAR BLUES ALBUM OF THE YEAR Man Machine PoeM The Tragically Hip THE InCorporateD*Universal Ride The One Paul ReddiCk Stony Plain*Warner VOCAL JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Bria Bria Skonberg Sony Hootenanny! Tim Neufeld & the Glory Boys InDepenDent JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR: SOLO WORLD MUSIC ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY CANADA Written in the Rocks Renee Rosnes Smoke Sessions*RED COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS) Okavango African Orchestra Okavango African Orchestra JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR: GROUP (SPONSORED BY STINGRAY MUSIC) InDepenDent Twenty Metalwood Cellar Live*MVD JACK RICHARDSON PRODUCER OF THE YEAR INSTRUMENTAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR A Tribe Called Red “R.E.D. -

Title: Song Analysis

Janine Pelletier, 2019 Werklund Graduate Title: Song Analysis - “We are the Halluci Nation” by A Tribe Called Red Subject: ELA 10, ELA 20, ELA 30 Time: 50 minutes Janine Pelletier was born in Calgary, Alberta. She has a life-long passion for literature and Indigenous studies, and strives to create inclusive, engaging learning activities with real world connections to enable her students to learn about the subject, themselves, and the world around them. Resources used and Song: “We Are the Halluci Nation” by A Tribe Called Red possible concerns Author/creator - A Tribe Called Red is an Indigenous DJ group out of and/or literature Ottawa, Canada made of 2 members, Bear Witness background and 2oolman. “They are part of a vital new generation of artists making a cultural and social impact in Canada alongside a renewed Aboriginal rights movement called Idle No More”. ("Press Kit - A Tribe Called Red", 2020). They have been producing music since 2008, and have a Juno win and a Polaris Music Prize short list appearance.. Their sound is a mix of modern hip-hop, traditional pow wow drums and vocals, blended with edgy electronic music production styles. - “The Halluci Nation [album] is a concept given to them by one of their idols, John Trudell, a renowned one-time leader in the American Indian Movement... it was written to include a broader audience of all races and backgrounds in promoting social justice. ("A Tribe Called Red The Halluci Nation Is Real", 2020) UPE course Literacy, Language, and Culture: connections (not - This lesson plan encourages students to view popular exhaustive) media as a text that can be analyzed to gain insight into different cultures. -

Music and Belonging / Musique Et Appartenance

Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance Joint meeting / Congrès mixte Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch Faculty of Music University of Toronto 25-27 May 2017 / 25-27 mai 2017 Welcome / Bienvenue The Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto is pleased to host the conference Canada 150: Music and Belonging / Musique et appartenance from May 25th to May 27th, 2017. This meeting brings together four Canadian scholarly societies devoted to music: CAML / ACBM (Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres / Association canadienne des bibliothèques, archives et centres de documentation musicaux), CSTM / SCTM (Canadian Society for Traditional Music / Société canadienne pour les traditions musicales), IASPM Canada (International Association for the Study of Popular Music, Canada Branch), and MusCan (Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes). We are expecting 300 people to attend the conference. As you will see in this program, there will be scholarly papers (ca. 200 of them), recitals, keynote speeches, workshops, an open mic session and a dance party – something for everyone. The multiple award winning Gryphon Trio will be giving a free recital for conference delegates on Friday evening, May 26th from 7:00 to 8:15 pm. Visitors also have the opportunity to take in many other Toronto events this weekend: music festivals by the Royal Conservatory of Music and CBC; concerts by Norah Jones, Rheostatics, The Weeknd, and the Toronto Symphony; a Toronto Blue Jays baseball game; the Inside Out LGBT Film Festival, and a host of other events at venues large and small across the city. -

Woloshyn.NAIMS Syllabus (Spring 2018)

NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS MUSIC SEMINAR (57-826) Class Meetings: Mondays and Wednesdays,10:30am-11:50am Room M157, CFA Instructor: Dr. Alexa Woloshyn (Call me Dr. Woloshyn or Prof. Woloshyn) Office: Room 160B, CFA Office Hours: Mondays/Wednesdays 3-5pm, or by appointment Telephone: 412-268-5451 Email: [email protected] Course Description: This course examines diverse Indigenous musical practices in North America, including powwow, round dance, intertribal flute music, and Inuit vocal games. We highlight the heterogeneity of Indigenous musical cultures both within specific practices and through the frequent engagement with non-Indigenous musical genres, such as the symphony, ballet, string quartet, and dubstep. This course pursues the understanding of diverse Indigenous musical practices through the lens of historical, socio-cultural Indigenous issues, such as cultural genocide and residential schools, sovereignty, identity, and decolonization. North American Indigenous Music Seminar challenges us as musicians and global citizens to engage with issues and musical practices not typically addressed in music studies. The diverse musical practices of Indigenous peoples in North America are an important cultural legacy, and this course equips us to examine a wide range of musical practices and issues. The course also requires us to build on critical listening and music analysis skills through application to both new (e.g., powwow) and familiar genres (e.g., symphony). This course will reinforce how music reflects and responds to the socio-cultural -

SSHRC and the Conscientious Community: Reflecting and Acting on Indigenous Research and Reconciliation in Response to TRC Call to Action 65

SSHRC think piece Franks October 2016 SSHRC and the Conscientious Community: reflecting and acting on Indigenous research and reconciliation in response to TRC Call to Action 65 Dr. Aaron Franks Mitacs-SSHRC Visiting Fellow in Indigenous Research and Reconciliation 1. Introduction The task of this short paper is to provide an informed, independent and critical perspective on the role of social sciences and humanities research in “advanc[ing] understanding of reconciliation” in Canada (TRC Call 65, 2015). Particular attention is given to the role of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) in shaping the discourse of reconciliation, and in supporting a research milieu and funding initiatives that reflect this vision. This paper is not a systematic review of existing initiatives, and certainly not a policy paper, official or otherwise. We are calling it a ‘think piece’, intended to push the edges of accepted thinking outward a bit, and I feel both privileged and daunted by the opportunity. While the paper was originally conceived by conference organizers to address “The Role of Research and Research Brokers in Reconciliation”, the focus has shifted to addressing the role of the social sciences and humanities in advancing understanding of reconciliation. 1.1. Paper outline The think-piece unfolds like this. You should know a bit about me, my positionality, and my relationship to SSHRC. And then how an ethic of decolonization frames my observations, deductions, my intuitions about practical action. In a short Section Two I name some of the contradictions we need to face to do this work, and then in Section Three I share a snapshot from the public discussion of reconciliation, in this case from a radio news program, and reflect on how the social sciences and humanities (with an admitted bias to the qualitative) can challenge, take apart and reconnect these discussions in important ways. -

Woloshyn CV (June 2019)

ALEXA WOLOSHYN Curriculum vitae School of Music Carnegie Mellon University 5000 Forbes Ave Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3815 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor in Musicology, Carnegie Mellon University, School of Music, 2016– Visiting Scholar, University of Toronto, Faculty of Music; Institute for Canadian Music, 2015– 2016 Visiting Instructor, Bowling Green State University (BGSU), College of Musical Arts, Department of Musicology/Composition/Theory, 2013–2015 Adjunct Instructor, University of Toronto, 2011–2013 Adjunct Instructor, University of Guelph, 2012 Adjunct Instructor, University of Western Ontario, 2011 EDUCATION PhD Musicology, Faculty of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 Dissertation: “The Recorded Voice and the Mediated Body in Contemporary Canadian Electroacoustic Music” MA Musicology, Department of Music Research & Composition, Don Wright Faculty of Music University of Western Ontario, 2007 BMus (History & Literature; French), Department of Music, University of Saskatchewan, 2005 SUPPLEMENTAL TRAINING Adult Mental Heath First Aid Certificate, valid 2018-2021 Online Instruction Certificate, George Brown Continuing Education, 2013 TATP Advanced University Teaching Preparation Certificate, Teaching Assistants’ Training Program (TATP), Centre for Teaching Support and Innovation (CTSI), University of Toronto, 2011 PUBLICATIONS (all single-authored unless otherwise noted) Refereed Journal Articles 2016 (2018) “A Tribe Called Red’s Halluci Nation: Sonifying Embodied Global Allegiances, Decolonization, and Indigenous Activism.” -

Polaris Music Prize Announces the 2017 Short List

POLARIS MUSIC PRIZE ANNOUNCES THE 2017 SHORT LIST TORONTO, ON – Thursday, July 13, 2017 The Polaris Music Prize, presented by CBC Music and produced by Blue Ant Media, today announced its 2017 Short List of 10 Canadian albums which will vie for the Polaris Music Prize being decided Sept. 18 in Toronto. The 2017 Short List was announced by CBC Radio 2 Morning host and Polaris juror Raina Douris. Douris will also host the Polaris Music Prize Gala, which will be held at The Carlu in Toronto and live-streamed at cbcmusic.ca/polaris and on CBC Music’s Facebook page and YouTube channel. 2017 Polaris Music Prize Short List: A Tribe Called Red – We Are The Halluci Nation BADBADNOTGOOD – IV Leonard Cohen – You Want It Darker Gord Downie – Secret Path Feist – Pleasure Lisa LeBlanc – Why You Wanna Leave, Runaway Queen? Lido Pimienta – La Papessa Tanya Tagaq – Retribution Leif Vollebekk – Twin Solitude Weaves – Weaves On CBC Radio 2 at 6 p.m. (6:30 p.m. NT) tonight, CBC Music will feature a special hour-long broadcast celebrating the Polaris Music Prize Short List on Drive with Rich Terfry. Tune in online or find your local CBC Radio 2 frequency at cbcmusic.ca/radio2, and visit cbcmusic.ca/polaris for more coverage. The eligibility period for the 2017 Polaris Music Prize runs from June 1, 2016 to May 31, 2017. An independent jury of music journalists, broadcasters and music bloggers from across Canada determines the Long List and Short List. Eleven people are selected from the larger jury pool to serve on the Grand Jury and they will convene the night of the gala to select the Polaris Music Prize winner. -

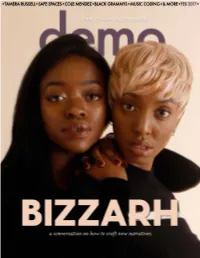

Tamera Russell•Safe Spaces•Cole Mendez•Black Grammys•Music Coding•& More•Feb 2017• Contents

•TAMERA RUSSELL•SAFE SPACES•COLE MENDEZ•BLACK GRAMMYS•MUSIC CODING•& MORE•FEB 2017• CONTENTS 04. 12. 26. 34. Staff Letters Looking Back Hand Over the Black Grammys Microphone 07. 13. 36. What Are You Life Under the 28. Weathering the Listening To? 6ix God Cole Mendez Modern Typhoon 08. 16. 29. 38. Educate, Create, Bizzarh Being South Asian Boy Better Know Cultivate Is A Blessing About Grime 22. 09. “Indie music is not 30. 40. New Sounds ‘white music’” Code Generation Best Albums of on Campus 2016 32. 24. Critiquing the 10. Thnks Fr Th 42. Spaces of Music Contributors Made of Soul: Msgny Criticism 02 Tamera Russell 03 masthead letters Melissa Vincent Stuart Oakes Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief I remember my introduction to demo vividly. After a chance meeting with this year’s In first year, four (and a half million) years ago (yes, I am old, and yes, I fear death), music coordinator, Aviva, in my first year, she did everything but drag me by the arm one of my professors narrativized that the graphic novel had blossomed as an artform to the first meeting, and I have had my feet firmly planted in thedemo community ever because no one paid any attention to it. If no one is paying attention, there are few since. Reminiscing on my experience has made me wonder not only how our writers rules. Demo can be read in much the same way: perched a little precariously on campus, stumbled into demo but exactly which of the magazine’s qualities keep them coming without the prestige of a literary journal but not quite cool enough to sit with the back. -

Of This Land, on This Land: Indigenous Artists Challenging the Racial Logics of Liberal Modernity Suzanne Morrissette a Disserta

OF THIS LAND, ON THIS LAND: INDIGENOUS ARTISTS CHALLENGING THE RACIAL LOGICS OF LIBERAL MODERNITY SUZANNE MORRISSETTE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO November 2017 © Suzanne Morrissette, 2017 ABSTRACT This dissertation discusses the role of Indigenous artists in illustrating and denaturalizing the systems of colonial thought that continue to constrain Indigenous peoples’ expressions of political agency. I argue that the works of select contemporary Indigenous artists challenge contemporary liberal settler society’s racial ideas of citizenship, belonging, and relationship to place through methods that involve diverse audiences in imagining more just and shared futures upon Indigenous lands. My examination of tendencies to frame Indigenous political expression as aggressive, anti-state, or anti-progress looks to literature on liberal thought, which describes concepts of freedom and equality manifested in the development of the social contract that has determined citizenship. I look at the ways that these concepts have been deployed historically to determine the value of Indigenous subjectivity and the supremacy of settler nations and institutions. In this sense, the artworks that I highlight engage critically with liberal thought, and also express Indigenous political thought in their own right. The analysis takes place in three parts: an examination of the history of ideas surrounding perceptions of Indigenous political presence; an investigation into the legacies of liberal thought now threatened by assertions of Indigenous political presence; and a study of the ways in which Indigenous people are misconstrued as violent even as they are the continued subjects of ongoing colonial violence. -

Indigenous Youth in Australia and Canada: a Modern Narrative of Settler/Colonial Relationships Through Indigenous Rap Music

Jonathon Potskin Indigenous Youth in Australia and Canada: a modern narrative of settler/colonial relationships through Indigenous rap music Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney July 2020 A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge; the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Signature* Jonathon Potskin 2 Acknowledgements I would like to firstly acknowledge the ancestors, the ancestors of the lands I mainly did my thinking and writing for this thesis, who are the ancestors of the Eora Nation. I would like to acknowledge my ancestors that help guide me in my journey throughout the earth. And for the present generations that are living amongst the lands of the Indigenous peoples I did my research on from western Australia’s Whadjuk Nyoongar people to the Gumbaynggirr people on the east coast of the continent, and in Canada being on the lands of the West Coast Salish people through the lands of the Cree, Blackfoot, Iroquois and Anishinabe of the great shield of Canada. This research is for the future, future generations of Indigenous youth around the world that are searching for their culture in modern times. Hip Hop in this research is representative of future cultures that influence and enhance a modern form of our ever-evolving cultures worldwide.