Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rumba in the Jungle Soukous Und Congotronics Aus Kinshasa

1 SWR2 MusikGlobal Rumba in the Jungle Soukous und Congotronics aus Kinshasa Von Arian Fariborz Sendung: Dienstag, 29.01.2019, 23:03 Uhr Redaktion: Anette Sidhu-Ingenhoff Produktion: SWR 2019 SWR2 MusikGlobal können Sie auch im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de und auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App hören Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Die neue SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app 2 SWR 2 MusikGlobal Die "Rumba Congolaise" – Afrikas neuer "Buena Vista Social Club" Von Arian Fariborz Länge: ca. 58:00 Redaktion: Anette Sidhu Musik 1 Mbongwana Star: „Malukayi“, CD From Kinshasa, Track 6, Länge: 6:02, Label: World Circuit, LC-Nummer: 02339, bis ca. 10 sec. als Musikbett unter Sprecher 1 legen, dann ausspielen und ab ca. 3:30 mit nachfolgender Atmo (Matongé) verblenden Sprecher 1 Heute in SWR 2 MusikGlobal: Die "Rumba Congolaise" – Afrikas neuer "Buena Vista Social Club". -

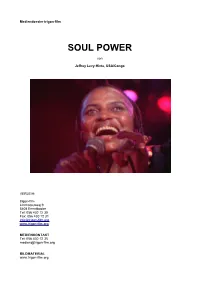

Pd Soul Power D

Mediendossier trigon-film SOUL POWER von Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, USA/Congo VERLEIH: trigon-film Limmatauweg 9 5408 Ennetbaden Tel: 056 430 12 30 Fax: 056 430 12 31 [email protected] www.trigon-film.org MEDIENKONTAKT Tel: 056 430 12 35 [email protected] BILDMATERIAL www.trigon-film.org MITWIRKENDE Regie: Jeffrey Levy-Hinte Kamera: Paul Goldsmith Kevin Keating Albert Maysles Roderick Young Montage: David Smith Produzenten: David Sonenberg, Leon Gast Produzenten Musikfestival Hugh Masekela, Stewart Levine Dauer: 93 Minuten Sprache/UT: Englisch/Französisch/d/f MUSIKER/ IN DER REIHENFOLGE IHRES ERSCHEINENS “Godfather of Soul” James Brown J.B.’s Bandleader & Trombonist Fred Wesley J.B.’s Saxophonist Maceo Parker Festival / Fight Promoter Don King “The Greatest” Muhammad Ali Concert Lighting Director Bill McManus Festival Coordinator Alan Pariser Festival Promoter Stewart Levine Festival Promoter Lloyd Price Investor Representative Keith Bradshaw The Spinners Henry Fambrough Billy Henderson Pervis Jackson Bobbie Smith Philippé Wynne “King of the Blues” B.B. King Singer/Songwriter Bill Withers Fania All-Stars Guitarist Yomo Toro “La Reina de la Salsa” Celia Cruz Fania All-Stairs Bandleader & Flautist Johnny Pacheco Trio Madjesi Mario Matadidi Mabele Loko Massengo "Djeskain" Saak "Sinatra" Sakoul, Festival Promoter Hugh Masakela Author & Editor George Plimpton Photographer Lynn Goldsmith Black Nationalist Stokely Carmichael a.k.a. “Kwame Ture” Ali’s Cornerman Drew “Bundini” Brown J.B.’s Singer and Bassist “Sweet" Charles Sherrell J.B.’s Dancers — “The Paybacks” David Butts Lola Love Saxophonist Manu Dibango Music Festival Emcee Lukuku OK Jazz Lead Singer François “Franco” Luambo Makiadi Singer Miriam Makeba Spinners and Sister Sledge Manager Buddy Allen Sister Sledge Debbie Sledge Joni Sledge Kathy Sledge Kim Sledge The Crusaders Kent Leon Brinkley Larry Carlton Wilton Felder Wayne Henderson Stix Hooper Joe Sample Fania All-Stars Conga Player Ray Barretto Fania All Stars Timbali Player Nicky Marrero Conga Musician Danny “Big Black” Ray Orchestre Afrisa Intern. -

Vernacular Resilience

Vernacular Resilience: An Approach to Studying Long- Term Social Practices and Cultural Repertoires of Resilience in Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of Congo Dieunedort Wandji, Jeremy Allouche and Gauthier Marchais About the STEPS Centre The ESRC STEPS (Social, Technological and Environmental Pathways to Sustainability) Centre carries out interdisciplinary global research uniting development studies with science and technology studies. Our pathways approach links theory, research methods and practice to highlight and open up the politics of sustainability. We focus on complex challenges like climate change, food systems, urbanisation and technology in which society and ecologies are entangled. Our work explores how to better understand these challenges and appreciate the range of potential responses to them. The STEPS Centre is hosted in the UK by the Institute of Development Studies and the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU) at the University of Sussex. Our main funding is from the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council. We work as part of a Global Consortium with hubs in Africa, China, Europe, Latin America, North America and South Asia. Our research projects, in many countries, engage with local problems and link them to wider concerns. Website: steps-centre.org Twitter: @stepscentre For more STEPS publications visit: steps-centre.org/publications This is one of a series of Working Papers from the STEPS Centre ISBN: 978-1-78118-793-7 DOI: 10.19088/STEPS.2021.001 © STEPS 2021 Vernacular Resilience: An Approach to Studying Long-Term Social Practices and Cultural Repertoires of Resilience in Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of Congo Dieunedort Wandji, Jeremy Allouche and Gauthier Marchais STEPS Working Paper 116 Correct citation: Wandji, D., Allouche, J. -

Londres Et Washington Ont Parlé. Sauf Surprise Improbable, Notre Pays Est Sauvé

i n t e r LEn PLUS fort TIragaE | LA PLUSt fortE VENTiE | LA PLUoS fortE A UDIEnNCE | DE to US aLES TEMPS l www.lesoftonline.net SINCE 1989 www.lesoft.be N°1207 | 1ÈRE ÉD. LUNDI 24 DÉCEMBCeRE 2012 | 24 PAGES €6 $7 CDF 4500 | FONDÉ À KI NSHASA futPAR TRYPHON KIN-KIEY MULUMBA la guerre de trop Londres et Washington ont parlé. Sauf surprise improbable, notre pays est sauvé Les Chefs de l’État rwandais Paul Kagame, congolais Joseph Kabila Kabange et ougandais Yoweri Museveni réunis à Kampala le 22 novembre 2012. DRÉSERVÉS. LE SOFT INTErnatIONAL EST UNE PUBLICatION DE DroIT ÉtrangER | AUTORISATION DE DIFFUSION EN R-dCongo M-CM/LMO/0321/MIN/08 DatÉ 13 JANVIER 2008 i n t e r n a t i o n a l www.lesoftonline.net SINCE 1989 www.lesoft.be La santé de Madiba inquiète e gouvernement par la majorité des Sud- l’hôpital depuis qu’il a été sud-africain Africains. Seuls les libéré de prison en 1990. restait muet services du président Nelson Mandela avait déjà dimanche au Jacob Zuma sont habilités été hospitalisé en janvier Lsujet de l’état de santé de à donner des informations 2011 pour une infection l’ancien président sud- sur l’état de santé du héros pulmonaire, probablement africain Nelson Mandela, de la lutte anti-apartheid. liée aux séquelles d’une laissant supposer qu’il La présidence n’a tuberculose contractée passera probablement pas donné beaucoup pendant son séjour à Noël à l’hôpital. d’indications sur la Robben Island où il a Admis dans un hôpital de gravité de l’état de santé passé 18 de ses 27 années Pretoria le 8 décembre, de Mandela ni de détails de captivité dans les Nelson Rolihlahla sur la nature du traitement geôles du régime raciste Mandela, dont le nom du qu’il suit. -

![Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021[ 165 ] 04:04:40PM Via Free Access LYE M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0022/downloaded-from-brill-com09-30-2021-165-04-04-40pm-via-free-access-lye-m-4740022.webp)

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021[ 165 ] 04:04:40PM Via Free Access LYE M

afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 165-171 LA LITTÉRATURE MUSICALE CONGOLAISE: LA FÊTE DES MOTS Lye M. Yoka Institut National des Arts (INA), Kinshasa, République Démoncratique du Congo Résumé Il existe bon nombre d’écrits sur la musique congolaise moderne, notamment sur le plan de l’histoire et de la sociologie. Mais pas d’écrits spécialisés sur la litteralité des textes des chansons en termes stylistique, parémiologique et thématique. Il faudrait en plus prendre en compte les sur- vivances tenaces des traditions orales avec cette culture épicée de l’ “éristique” qui est l’art de la dis- pute et de la palabre, assorti des artifices de la satire et de circonlocutions plus ou moins subversives. Finalement ce que les critiques “puristes” considèrent comme “paralittérature” (terme passablement dépréciatif!) c’est de la littérature en bonne et due forme. MOTS CLÉS : LITTÉRATURE MUSICALE, ODYSSÉE ET ÉPOPÉE DE LA RUMBA CONGOLAISE, CARACTÈRES TRANSPHRAS- TIQUE ET SYNTAGMATIQUE, TRAVESTISSEMENT DES PROFÉRATIONS THÉMATIQUES, RÉINVENTIONS PARÉMIOLOGIQUES Abstract Much has been written on modern Congolese music, particularly in terms of its history and sociology. However, there are no studies dedicated to the literary qualities of the song texts in stylistic, paremiological and thematic terms. In addition, when considering this body of music, the tenacious survival of oral traditions should be taken into account. Such traditions take in the vivid culture of the “eristic”, the art of dispute and energetic discussion, accompanied by satirical turns and more or less subversive circumlocutions. Finally, assert that what “purist” critics consider as “para-literature” (a rather deprecating term) is literature both in terms of its thematic and formal concerns. -

La Littérature Musicale Congolaise: La Fête Des Mots

afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 165-171 LA LITTÉRATURE MUSICALE CONGOLAISE: LA FÊTE DES MOTS Lye M. Yoka Institut National des Arts (INA), Kinshasa, République Démoncratique du Congo Résumé Il existe bon nombre d’écrits sur la musique congolaise moderne, notamment sur le plan de l’histoire et de la sociologie. Mais pas d’écrits spécialisés sur la litteralité des textes des chansons en termes stylistique, parémiologique et thématique. Il faudrait en plus prendre en compte les sur- vivances tenaces des traditions orales avec cette culture épicée de l’ “éristique” qui est l’art de la dis- pute et de la palabre, assorti des artifices de la satire et de circonlocutions plus ou moins subversives. Finalement ce que les critiques “puristes” considèrent comme “paralittérature” (terme passablement dépréciatif!) c’est de la littérature en bonne et due forme. MOTS CLÉS : LITTÉRATURE MUSICALE, ODYSSÉE ET ÉPOPÉE DE LA RUMBA CONGOLAISE, CARACTÈRES TRANSPHRAS- TIQUE ET SYNTAGMATIQUE, TRAVESTISSEMENT DES PROFÉRATIONS THÉMATIQUES, RÉINVENTIONS PARÉMIOLOGIQUES Abstract Much has been written on modern Congolese music, particularly in terms of its history and sociology. However, there are no studies dedicated to the literary qualities of the song texts in stylistic, paremiological and thematic terms. In addition, when considering this body of music, the tenacious survival of oral traditions should be taken into account. Such traditions take in the vivid culture of the “eristic”, the art of dispute and energetic discussion, accompanied by satirical turns and more or less subversive circumlocutions. Finally, assert that what “purist” critics consider as “para-literature” (a rather deprecating term) is literature both in terms of its thematic and formal concerns. -

Downbeat.Com June 2010 U.K. £3.50

.K. £3.50 .K. u downbeat.com June 2010 2010 June DownBeat ChiCk Corea // Bill Evans // wallaCe Roney // Bobby Broom // 33rd Annual StuDent Music AwarDs June 2010 June 2010 Volume 77 – Number 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser AdVertisiNg Sales Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] offices 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] customer serVice 877-904-5299 [email protected] coNtributors Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Marga- sak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Nor- man Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Go- logursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer Odell, Dan Ouellette, Ted -

Multimedia Suggested List

ANGOLA ARTIST Nastio Mosquito (1981 - ) - Specialty: Contemporary Artist ARUBA ARTIST Frederick Hendrick (Henry) Habibi (1940 - ) - Specialty: Poet, Literary Critic - Most of his poems are written in Papiamento AUSTRALIA ARTIST Gloria Petyarre (aka Gloria Pitjara) (1945 - ) - Specialty: Aboriginal artist. Her works are considered highly collectible; prices range from $2,000 - $30,000. AUTHORS Faith Bandler (1918 – 2015) - Specialty: Writer Mary Carmel Charles - Specialty: Writer Alexis Wright - Specialty: Writer Kate Howarth - Specialty: Writer Glenyse Ward - Specialty: Writer Fifty Shades of Brown: Sources for Building Ethnic-Centered Community Collections for New Americans of Color by Wilma Kakie Glover-Koomson 1 BARBADOS AUTHORS Austin Clarke (A.C.) (1934 - ) - Specialty: Novelist, Short Story, and Essayist - Bibliography: The Polished Hoe; Storm of Fortune; Survivors of the Crossing Kwadwo Agymah Kamau - Specialty: Writer - Bibliography: Pictures of a Dying Man; Flickering Shadows Karen Lord (1968 - ) - Specialty: Writer - Bibliography: Redemption in Indigo; The Best of All Possible Worlds Glenville Lovell (1955 - ) - Specialty: Writer, Dancer, and Playwright - Bibliography: Fire in the Canes; Song of Night; Mango Ripe! Mango Sweet (play) George Lamming (1927 - ) - Specialty: Novelist, Poet, and Essayist - Bibliography: In the Castle of My Skin; Natives of My Person; The Pleasures of Exile – Essays MUSIC/MUSICIANS/LABELS Arturo Tappin Rihanna (aka Robyn Rihanna Fenty) (1988 - ) - Specialty: Singer, Songwriter - Albums: Unapologetic; Talk that Talk; Loud; Good Girl Born Bad; Rated R Shontelle Layne (1985 - ) - Specialty: Singer BENIN ARTISTS Meschach Gaba (1961 - ) - Specialty: Artist (Contemporary African and Cultural), Sculptor - Bibliography: Meschac Gaba by Stephen Muller (August 2010) MUSIC/MUSICIANS/LABELS Angelique Kidjo Wally Badarou Fifty Shades of Brown: Sources for Building Ethnic-Centered Community Collections for New Americans of Color by Wilma Kakie Glover-Koomson 2 BRITAIN AUTHOR V.S. -

ETD Template

THE RECONTEXTUALIZATION OF AFRICAN MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES: A CASE STUDY OF UMOJA AFRICAN ARTS COMPANY by Anicet Mudimbenga Mundundu BA, Université Nationale du Zaire, 1981 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Anicet Mudimbenga Mundundu It was defended on 18 April, 2005 and approved by Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Ph.D., Professor of Music Dissertation Co-Chair Dr. Akin O. Euba, Ph.D., Professor of Music Dr. Matthew Rosenblum, Ph.D., Professor of Music Professor (Emeritus) J. H. Kwabena Nketia, Professor of Music Dissertation Co-Chair ii © Anicet M. Mundundu 2005 iii THE RECONTEXTUALIZATION OF AFRICAN MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES: A CASE STUDY OF UMOJA AFRICAN ARTS COMPANY Anicet M. Mundundu, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation is about the opportunities and challenges posed by the presentation and interpretation of African music performances by African immigrants in Western contexts in general and the United States in particular. The study focuses on the experience of the Umoja African Arts Company, a Pittsburgh based repertory dance ensemble that performs music and dance from various parts of Africa. Although much has been observed on the contribution of Africa to the development of the American music and dance experience, there is a growing interest among African scholars to question the relevance, impact and the analysis of the emerging efforts of new African immigrants in the promotion of African music in changing contexts overseas where creative individuals have to reconfigure new ways of interpreting and presenting cultural resources to diverse audiences. -

Various Golden Afrique (The Great Days of Rumba Congolaise and Early Soukous) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Golden Afrique (The Great Days Of Rumba Congolaise And Early Soukous) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Golden Afrique (The Great Days Of Rumba Congolaise And Early Soukous) Country: UK Released: 2013 Style: African, Rumba, Soukous MP3 version RAR size: 1616 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1489 mb WMA version RAR size: 1332 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 932 Other Formats: VQF RA DMF AC3 APE MMF MOD Tracklist Hide Credits –Franco Luambo Makiadi* & Sam 1-01 Coopération 12:08 Mangwana 1-02 –Nyboma* Doublé-Doublé 8:12 1-03 –Grand Kalle & African Jazz* Africa Mokili Mobimba 5:07 Indépendance Cha Cha Cha 1-04 –Grand Kalle & African Jazz* Bass Guitar – Brazzo*Guitar – Docteur 3:04 Nico*Voice – Roger Iziedi*, Vicky Longomba Siluwangi Wapi Accordeon 1-05 –Franco & O.K. Jazz* & Camille Feruzi 3:53 Accordion [Button] – Camille Feruzi 1-06 –Sam Mangwana Marabenta (Vamos Para O Campo) 7:48 1-07 –Les Bantous De La Capitale Machette 9:12 1-08 –Franco & O.K. Jazz* Lina 3:12 1-09 –Franco & O.K. Jazz* Tcha Tcha Tcha De Mi Amor 3:12 –Docteur Nico* & Orchestre African 1-10 Exhibition Dechaud 3:36 Fiesta* 1-11 –Docteur Nico* & Africa Fiesta Sukisa* Pauline 4:46 Bawayo Guitar [Electric] – Dizzy MandjekuSaxophone – 1-12 –Tiers Monde Coopération* 9:16 Empompo Deyess Loway*Vocals – Sam Mangwana 2-01 –Mose Fan Fan Pele Odija 7:49 Mambo Ry-Co 2-02 –Ry-Co Jazz* 3:59 Guitar – Jerry Malekani 2-03 –Camille Feruzi Cha Cha Cha Bay 2:59 2-04 –Léon Bukasa Bibi Yangu 3:07 2-05 –M'Pongo Love Ndaya 9:03 Bika Nzanga 2-06 –Le Likembé Géant 4:36 Conductor – André Nkouka –Tabu Ley Rochereau & Sam 2-07 Como Bacalao 2:50 Mangwana Mazé 2-08 –Tabu Ley Rochereau 10:34 Saxophone – Modero Mekanisi 2-09 –Manu Dibango Ekedy 2:50 2-10 –K.P. -

Composing Civil Society: Ethnographic Contingency, NGO Culture, and Music Production in Nairobi, Kenya Matthew Mcnamara Morin

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Composing Civil Society: Ethnographic Contingency, NGO Culture, and Music Production in Nairobi, Kenya Matthew McNamara Morin Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COMPOSING CIVIL SOCIETY: ETHNOGRAPHIC CONTINGENCY, NGO CULTURE, AND MUSIC PRODUCTION IN NAIROBI, KENYA By MATTHEW MCNAMARA MORIN A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2012 Copyright © 2012 Matthew McNamara Morin All Rights Reserved Matthew McNamara Morin defended this dissertation on November 6, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Frank Gunderson Professor Directing Dissertation Ralph Brower University Representative Michael B. Bakan Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my father, Charles Leon Morin. I miss our conversations more than ever these days. Through teaching, you made a positive difference in so many lives. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I thank my wife and soul mate, Shino Saito. From coursework to prospectus, to a working fieldwork honeymoon in Nairobi, through the seemingly endless writing process to which you contributed countless proofreads and edits, you were an integral contributor to anything good within this text. I am looking forward to the wonderful years ahead with our new family member, and I hope to show the same support for you that you have shown me. -

Joseph Kabasele

Joseph Kabasele - le Grand Kallé, tel qu'il était connu par ses collègues, ses fans, et même des chefs d'État - est au cœur même de la grande mosaïque que représente la musique populaire africaine. Sans lui, l'image de cette mosaïque serait méconnaissable. C'est pendant la période turbulente et euphorique qui a entouré l'indépendance du Congo, en 1960, que Kallé et son groupe de rumba, l'orchestre African Jazz, formé avec notamment des musiciens tels que Manu Dibango, Dr Nico et Tabu Ley Rochereau, eut le plus d'influence en Afrique. Depuis, leur musique s'est faite entendre dans le monde entier. Intégrant des enregistrements épuisés depuis des décennies ainsi que les morceaux les plus célèbres et les plus durables de Kabasele, ce double album s'accompagne d'un livret fort documenté et illustré de 104 pages qui nous fait découvrir l'homme, sa musique et son contexte comme jamais auparavant. Le Grand Kallé Le monde s'est largement servi au Congo, une région située au cœur même de l'Afrique, en lui prenant des esclaves, de l'ivoire et de la faune, du bois et du caoutchouc, des diamants et des métaux rares. La musique était la seule chose donnée et reçue avec un plaisir honnête. C'est en 1526 que le monde a entendu parler de musique congolaise pour la première fois, lorsque les Européens et les marchands d'esclaves africains ont commencé la traite du peuple congolais vers les Amériques. Au cours des trois siècles et demie qui suivirent, le trafic transatlantique déracina quatre millions d'hommes, de femmes et d'enfants de la région du Congo - soit deux fois plus que de toute autre partie de l'Afrique.