Thomas David Anderson – Watcher of the Skies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Meeting Announcement Upcoming Star Parties And

CVAS Executive Committee Pres – Bruce Horrocks Night Sky Network Coordinator – [email protected] Garrett Smith – [email protected] Vice Pres- James Somers Past President – Dell Vance (435) 938-8328 [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer- Janice Bradshaw Public Relations – Lyle Johnson - [email protected] [email protected] Secretary – Wendell Waters (435) 213-9230 Webmaster, Librarian – Tom Westre [email protected] [email protected] Vol. 7 Number 6 February 2020 www.cvas-utahskies.org The President’s Corner Meeting Announcement By Bruce Horrocks – CVAS President Our next meeting will be held on Wed. I don’t know about most of you, but I for February 26th at 7 pm in the Lake Bonneville Room one would be glad to at least see a bit of sun and of the Logan City Library. Our presenter will be clear skies at least once this winter. I believe there Wendell Waters, and his presentation is called was just a couple of nights in the last 2 months that “Charles Messier and the ‘Not-Comet’ Catalogue”. I was able to get out and do some observing and so I The meeting is free and open to the public. am hoping to see some clear skies this spring. I Light refreshments will be served. COME AND have watched all the documentaries I can stand on JOIN US!! Netflix, so I am running out of other nighttime activities to do and I really want to get out and test my new little 72mm telescope. Upcoming Star Parties and CVAS Events We made a change to our club fees at our last meeting and if you happened to have missed We have four STEM Nights coming up in that I will just quickly explain it to you now. -

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

The State of Anthro–Earth

The Rosette Gazette Volume 22,, IssueIssue 7 Newsletter of the Rose City Astronomers July, 2010 RCA JULY 19 GENERAL MEETING The State Of Anthro–Earth THE STATE OF ANTHRO-EARTH: A Visitor From Far, Far Away Reviews the Status of Our Planet In This Issue: A Talk (in Earth-English) By Richard Brenne 1….General Meeting Enrico Fermi famously wondered why we hadn't heard from any other planetary 2….Club Officers civilizations, and Richard Brenne, who we'd always suspected was probably from another planet, thinks he might know the answer. Carl Sagan thought it was likely …...Magazines because those on other planets blew themselves up with nuclear weapons, but Richard …...RCA Library thinks its more likely that burning fossil fuels changed the climates and collapsed the 3….Local Happenings civilizations of those we might otherwise have heard from. Only someone from another planet could discuss this most serious topic with Richard's trademark humor 4…. Telescope (in a previous life he was an award-winning screenwriter - on which planet we're not Transformation sure) and bemused detachment. 5….Special Interest Groups Richard Brenne teaches a NASA-sponsored Global Climate Change class, serves on 6….Star Party Scene the American Meteorological Society's Committee to Communicate Climate Change, has written and produced documentaries about climate change since 1992, and has 7.…Observers Corner produced and moderated 50 hours of panel discussions about climate change with 18...RCA Board Minutes many of the world's top climate change scientists. Richard writes for the blog "Climate Progress" and his forthcoming book is titled "Anthro-Earth", his new name 20...Calendars for his adopted planet. -

Una Aproximación Física Al Universo Local De Nebadon

4 1 0 2 local Nebadon de Santiago RodríguezSantiago Hernández Una aproximación física al universo (160.1) 14:5.11 La curiosidad — el espíritu de investigación, el estímulo del descubrimiento, el impulso a la exploración — forma parte de la dotación innata y divina de las criaturas evolutivas del espacio. Tabla de contenido 1.-Descripción científica de nuestro entorno cósmico. ............................................................................. 3 1.1 Lo que nuestros ojos ven. ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Lo que la ciencia establece ............................................................................................................... 4 2.-Descripción del LU de nuestro entorno cósmico. ................................................................................ 10 2.1 Universo Maestro ........................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Gran Universo. Nivel Espacial Superunivesal ................................................................................. 13 2.3 Orvonton. El Séptimo Superuniverso. ............................................................................................ 14 2.4 En el interior de Orvonton. En la Vía Láctea. ................................................................................. 18 2.5 En el interior de Orvonton. Splandon el 5º Sector Mayor ............................................................ 19 -

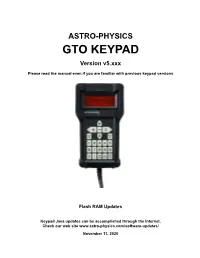

GTO Keypad Manual, V5.001

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v5.xxx Please read the manual even if you are familiar with previous keypad versions Flash RAM Updates Keypad Java updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com/software-updates/ November 11, 2020 ASTRO-PHYSICS KEYPAD MANUAL FOR MACH2GTO Version 5.xxx November 11, 2020 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 4 REQUIREMENTS 5 What Mount Control Box Do I Need? 5 Can I Upgrade My Present Keypad? 5 GTO KEYPAD 6 Layout and Buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent Display 6 N-S-E-W Directional Buttons 6 STOP Button 6 <PREV and NEXT> Buttons 7 Number Buttons 7 GOTO Button 7 ± Button 7 MENU / ESC Button 7 RECAL and NEXT> Buttons Pressed Simultaneously 7 ENT Button 7 Retractable Hanger 7 Keypad Protector 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad Battery for 512K Memory Boards 8 Cleaning Red Keypad Display 8 Temperature Ratings 8 Environmental Recommendation 8 GETTING STARTED – DO THIS AT HOME, IF POSSIBLE 9 Set Up your Mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather Basic Information 9 Enter Your Location, Time and Date 9 Set Up Your Mount in the Field 10 Polar Alignment 10 Mach2GTO Daytime Alignment Routine 10 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR NEW SETUPS OR SETUP IN NEW LOCATION 11 Assemble Your Mount 11 Startup Sequence 11 Location 11 Select Existing Location 11 Set Up New Location 11 Date and Time 12 Additional Information 12 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR MOUNTS USED AT THE SAME LOCATION WITHOUT A COMPUTER 13 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR COMPUTER CONTROLLED MOUNTS 14 1 OBJECTS MENU – HAVE SOME FUN! -

![Arxiv:2006.10868V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut D’Estudis Espacials De Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`A2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3592/arxiv-2006-10868v2-astro-ph-sr-9-apr-2021-spain-and-institut-d-estudis-espacials-de-catalunya-ieec-c-gran-capit-a2-4-e-08034-2-serenelli-weiss-aerts-et-al-1213592.webp)

Arxiv:2006.10868V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut D’Estudis Espacials De Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`A2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts Et Al

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Weighing stars from birth to death: mass determination methods across the HRD Aldo Serenelli · Achim Weiss · Conny Aerts · George C. Angelou · David Baroch · Nate Bastian · Paul G. Beck · Maria Bergemann · Joachim M. Bestenlehner · Ian Czekala · Nancy Elias-Rosa · Ana Escorza · Vincent Van Eylen · Diane K. Feuillet · Davide Gandolfi · Mark Gieles · L´eoGirardi · Yveline Lebreton · Nicolas Lodieu · Marie Martig · Marcelo M. Miller Bertolami · Joey S.G. Mombarg · Juan Carlos Morales · Andr´esMoya · Benard Nsamba · KreˇsimirPavlovski · May G. Pedersen · Ignasi Ribas · Fabian R.N. Schneider · Victor Silva Aguirre · Keivan G. Stassun · Eline Tolstoy · Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay · Konstanze Zwintz Received: date / Accepted: date A. Serenelli Institute of Space Sciences (ICE, CSIC), Carrer de Can Magrans S/N, Bellaterra, E- 08193, Spain and Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), Carrer Gran Capita 2, Barcelona, E-08034, Spain E-mail: [email protected] A. Weiss Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching bei M¨unchen, D-85741, Germany C. Aerts Institute of Astronomy, Department of Physics & Astronomy, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium and Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, Radboud University Nijmegen, Heyendaalseweg 135, 6525 AJ Nijmegen, the Netherlands G.C. Angelou Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching bei M¨unchen, D-85741, Germany D. Baroch J. C. Morales I. Ribas Institute of· Space Sciences· (ICE, CSIC), Carrer de Can Magrans S/N, Bellaterra, E-08193, arXiv:2006.10868v2 [astro-ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`a2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts et al. -

Why Do Hydrogen and Helium Migrate from Some Planets and Smaller

Why do Hydrogen and Helium Migrate from Some Planets and Smaller Objects? Author Weitter Duckss Independent Researcher, Zadar, Croatia mail: [email protected] Project: https://www.svemir-ipaksevrti.com/ Abstract This article analyzes the processes through measuring the material incoming from the outer space onto Earth, through migrating of hydrogen and helium from our atmosphere and from other objects and through inability to detect the radioactive effects on stars and objects with melted interiorities. Habitable periods on such objects are determined through the processes. 1. Introduction The goal of the article is to give arguments, based on the existing data bases, that a constant growth of space objects, as well as their rotation and tidal forces, cause their warming up and radiation emissions, therefore making radioactive processes of fission and fusion – which are not detected on stars and other objects anyway – unnecessary. The article gives evidence of hydrogen and helium migrating towards the objects that have more mass and of temperature levels of stars being directly related to their chemical compositions and the objects in their orbits. The argumentation to support a habitable period will be derived from the natural processes of constant growth and matter gathering. 2. Why there is no radioactive emission, derived from the processes of fission and fusion, inside stars? All data bases indicate that astronomic research (or, evidence) support the existence of a constant (monotonous), omnipresent, slow gathering of matter. The processes are "more accelerated" in such part of the Universe where there is more matter gathered (in the form of nebulae, molecular clouds, etc.) during a long period of time, but gathering takes place constantly in the whole volume of the Universe as well. -

Desert Skies Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association

Desert Skies Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association Volume LIII, Number 12 December, 2007 Happy Holidays! ♦ TAAA Holiday Party ♦ Object of the Month ♦ School star parties ♦ Constellation of the month ♦ TAAA Dark Site Update Desert Skies: December, 2007 2 Volume LIII, Number 12 Cover Photo: Sunset over Kitt Peak. Taken by Dean Ketelsen using a Canon 20DA. TAAA Web Page: http://www.tucsonastronomy.org TAAA Phone Number: (520) 792-6414 Office/Position Name Phone E-mail Address President Bill Lofquist 297-6653 [email protected] Vice President Ken Shaver 762-5094 [email protected] Secretary Steve Marten 307-5237 [email protected] Treasurer Terri Lappin 977-1290 [email protected] Member-at-Large George Barber 822-2392 [email protected] Member-at-Large Keith Schlottman 290-5883 [email protected] Member-at-Large Teresa Plymate 883-9113 [email protected] Chief Observer Wayne Johnson 586-2244 [email protected] AL Correspondent (ALCor) Nick de Mesa 797-6614 [email protected] Astro-Imaging SIG Steve Peterson 762-8211 [email protected] Computers in Astronomy SIG Roger Tanner 574-3876 [email protected] Beginners SIG JD Metzger 760-8248 [email protected] Newsletter Editor George Barber 822-2392 [email protected] School Star Party Scheduling Coordinator Paul Moss 240-2084 [email protected] School Star Party Volunteer Coordinator Claude Plymate 883-9113 [email protected] -

Research and Scientific Support Department 2003 – 2004

COVER 7/11/05 4:55 PM Page 1 SP-1288 SP-1288 Research and Scientific Research Report on the activities of the Support Department Research and Scientific Support Department 2003 – 2004 Contact: ESA Publications Division c/o ESTEC, PO Box 299, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands Tel. (31) 71 565 3400 - Fax (31) 71 565 5433 Sec1.qxd 7/11/05 5:09 PM Page 1 SP-1288 June 2005 Report on the activities of the Research and Scientific Support Department 2003 – 2004 Scientific Editor A. Gimenez Sec1.qxd 7/11/05 5:09 PM Page 2 2 ESA SP-1288 Report on the Activities of the Research and Scientific Support Department from 2003 to 2004 ISBN 92-9092-963-4 ISSN 0379-6566 Scientific Editor A. Gimenez Editor A. Wilson Published and distributed by ESA Publications Division Copyright © 2005 European Space Agency Price €30 Sec1.qxd 7/11/05 5:09 PM Page 3 3 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 5 4. Other Activities 95 1.1 Report Overview 5 4.1 Symposia and Workshops organised 95 by RSSD 1.2 The Role, Structure and Staffing of RSSD 5 and SCI-A 4.2 ESA Technology Programmes 101 1.3 Department Outlook 8 4.3 Coordination and Other Supporting 102 Activities 2. Research Activities 11 Annex 1: Manpower Deployment 107 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 High-Energy Astrophysics 14 Annex 2: Publications 113 (separated into refereed and 2.3 Optical/UV Astrophysics 19 non-refereed literature) 2.4 Infrared/Sub-millimetre Astrophysics 22 2.5 Solar Physics 26 Annex 3: Seminars and Colloquia 149 2.6 Heliospheric Physics/Space Plasma Studies 31 2.7 Comparative Planetology and Astrobiology 35 Annex 4: Acronyms 153 2.8 Minor Bodies 39 2.9 Fundamental Physics 43 2.10 Research Activities in SCI-A 45 3. -

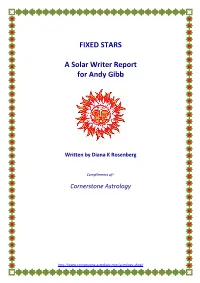

Fixed Stars Report

FIXED STARS A Solar Writer Report for Andy Gibb Written by Diana K Rosenberg Compliments of:- Cornerstone Astrology http://www.cornerstone-astrology.com/astrology-shop/ Table of Contents · Chart Wheel · Introduction · Fixed Stars · The Tropical And Sidereal Zodiacs · About this Report · Abbreviations · Sources · Your Starsets · Conclusion http://www.cornerstone-astrology.com/astrology-shop/ Page 1 Chart Wheel Andy Gibb 49' 44' 29°‡ Male 18°ˆ 00° 5 Mar 1958 22' À ‡ 6:30 am UT +0:00 ‰ ¾ ɽ 44' Manchester 05° 04°02° 24° 01° ‡ ‡ 53°N30' 46' ˆ ‡ 33'16' 002°W15' ‰ 56' Œ 10' Tropical ¼ Œ Œ 24° 21° 9 8 Placidus ‰ 10 » 13' 04° 11 Š ‘‘ 42' 7 ’ ¶ á ’ …07° 12 ” 05' ” ‘ 06° Ï 29° 29' … 29° Œ45' … 00° Á àà Š à „ 24' ‘ 24' 11' á 6 14°‹ á ¸ 28' Œ14' 15°‹ 1 “ „08° º 5 ¿ 4 2 3 Œ 46' 16' ƒ Ý 24° 02° 22' Ê ƒ 00° 05° Ý 44' 44' 18°‚ 29°Ý 49' http://www.cornerstone-astrology.com/astrology-shop/ Page 2 Astrological Summary Chart Point Positions: Andy Gibb Planet Sign Position House Comment The Moon Virgo 7°Vi05' 7th The Sun Pisces 14°Pi11' 1st Mercury Pisces 15°Pi28' 1st Venus Aquarius 4°Aq42' 12th Mars Capricorn 21°Cp13' 11th Jupiter Scorpio 1°Sc10' 8th Saturn Sagittarius 24°Sg56' 10th Uranus Leo 8°Le14' 6th Neptune Scorpio 4°Sc33' 8th Pluto Virgo 0°Vi45' 7th The North Node Scorpio 2°Sc16' 8th The South Node Taurus 2°Ta16' 2nd The Ascendant Aquarius 29°Aq24' 1st The Midheaven Sagittarius 18°Sg44' 10th The Part of Fortune Virgo 6°Vi29' 7th http://www.cornerstone-astrology.com/astrology-shop/ Page 3 Chart Point Aspects Planet Aspect Planet Orb App/Sep The Moon -

Extrasolar Planet Detection and Characterization with the KELT-North Transit Survey

Extrasolar Planet Detection and Characterization With the KELT-North Transit Survey DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas G. Beatty Graduate Program in Astronomy The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor B. Scott Gaudi, Advisor Professor Andrew P. Gould Professor Marc H. Pinsonneault Copyright by Thomas G. Beatty 2014 Abstract My dissertation focuses on the detection and characterization of new transiting extrasolar planets from the KELT-North survey, along with a examination of the processes underlying the astrophysical errors in the type of radial velocity measurements necessary to measure exoplanetary masses. Since 2006, the KELT- North transit survey has been collecting wide-angle precision photometry for 20% of the sky using a set of target selection, lightcurve processing, and candidate identification protocols I developed over the winter of 2010-2011. Since our initial set of planet candidates were generated in April 2011, KELT-North has discovered seven new transiting planets, two of which are among the five brightest transiting hot Jupiter systems discovered via a ground-based photometric survey. This highlights one of the main goals of the KELT-North survey: to discover new transiting systems orbiting bright, V< 10, host stars. These systems offer us the best targets for the precision ground- and space-based follow-up observations necessary to measure exoplanetary atmospheres. In September 2012 I demonstrated the atmospheric science enabled by the new KELT planets by observing the secondary eclipses of the brown dwarf KELT-1b with the Spitzer Space Telescope.