National Council of Applied Economic Research Study on Agricultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resurgent Bihar

Resurgent Bihar June 2012 PHD RESEARCH BUREAU PHD CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY PHD House, 4/2 Siri Institutional Area, August Kranti Marg, New Delhi 110016 Phone: 91-11-26863801-04, 49545454, Fax: 91-11-26855450, 26863135 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.phdcci.in Resurgent Bihar DISCLAIMER Resurgent Bihar is prepared by PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry to study the economy of Bihar. This report may not be reproduced, wholly or partly in any material form, or modified, without prior approval from PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry. It may please be noted that this report is for guidance and information purposes only. Though Foreword due care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information to the best of the PHD Chamber's knowledge and belief, it is strongly recommended that the readers should seek Bihar is a treasure house of opportunities with immense potential arising out of specific professional advice before making any decisions. the rich mineral reserves and a large base of immensely talented rural human Sandip Somany resource. The state provides for a perfect mix of the traditional with the modern, Please note that the PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry does not take any responsibility for President making it an ideal platform for pilgrimage as well as rural tourism. outcome of decisions taken as a result of relying on the content of this report. PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry shall in no way, be liable for any direct or indirect damages that may arise due to any act or omission on the part of the Reader or User due to any reliance placed or Historically known as a low income economy with weak infrastructure and a guidance taken from any portion of this publication. -

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

Brief Industrial Profile of PURNEA District

P a g e | 1 G o v e r n m e n t o f I n d i a M in is t r y of M S M E Brief Industrial Profile of PURNEA District Carried out by MS ME - D e v e l opme nt I ns ti tute , M uz a ff a r pur (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone :-0621-2284425 Fax: 0621-2282486 e-mail:[email protected] Web- www.msmedimzfpur.bih.nic.in Page | 2 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 4 1.2 Topography 5-6 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 7 1.4 Forest 8 1.5 Administrative set up 8-9 2. District at a glance 9-14 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Purnia 14 3. Industrial Scenario Of Purnia 15 3.1 Industry at a Glance - 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 16 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 17 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 18 3.5 Major Exportable Item 18 3.6 Growth Trend 18 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 18 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 18 3.8.1 List of the units in –PURNEA ---- & near by Area 18 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 18 3.9.1 Coaching Industry 19 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 19 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 19 4. -

Service Sector Impact on Economic Growth of Bihar: an Econometric Investigation

Indian Journal of Agriculture Business Volume 6 Number 1, January - June 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21088/ijab.2454.7964.6120.2 Orignal Article Service Sector Impact on Economic Growth of Bihar: An Econometric Investigation Rinky Kumari How to cite this article: Rinky Kumari. Service Sector Impact on Economic Growth of Bihar: An Econometric Investigation. Indian Journal of Agriculture Business 2020;6(1):15–26. Author’s Af liation Abstract Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Patna University, Patna 800005, Bihar, India. The objective of this study is to examine the service sector impacts on economic growth of Bihar, since it plays an important role in contributing Coressponding Author: in Bihar’s GSDP. At the all India Level, services share has increased at a Rinky Kumari, Research Scholar, greater rate than industry after 2003-05 while in Bihar, services through Department of Economics, Patna University, Patna 800005, Bihar, India. have easily increased at a greater rate than agriculture. The economy of Bihar is largely service oriented, but it also has a significant agricultural E-mail: [email protected] base. This study discusses the nature of growth of services in Bihar and compare with the overall India level. This study also look into the sectoral contribution of services in Bihar and other important feature of the services led growth in the state. India has experience rapid change in the growth of service sector since 1990-91, to become the economy’s leading sector, during the same period services in Bihar have too up grown. The study also find that there are variations in growth and performance of different sub-sectors of services. -

Compendium of Best Practices on Anti Human Trafficking

Government of India COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS Acknowledgments ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ms. Ashita Mittal, Deputy Representative, UNODC, Regional Office for South Asia The Working Group of Project IND/ S16: Dr. Geeta Sekhon, Project Coordinator Ms. Swasti Rana, Project Associate Mr. Varghese John, Admin/ Finance Assistant UNODC is grateful to the team of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi for compiling this document: Ms. Bharti Ali, Co-Director Ms. Geeta Menon, Consultant UNODC acknowledges the support of: Dr. P M Nair, IPS Mr. K Koshy, Director General, Bureau of Police Research and Development Ms. Manjula Krishnan, Economic Advisor, Ministry of Women and Child Development Mr. NS Kalsi, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs Ms. Sumita Mukherjee, Director, Ministry of Home Affairs All contributors whose names are mentioned in the list appended IX COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS © UNODC, 2008 Year of Publication: 2008 A publication of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office for South Asia EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110 021 www.unodc.org/india Disclaimer This Compendium has been compiled by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights for Project IND/S16 of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily represent the official policy of the Government of India or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The designations used do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, frontiers or boundaries. -

About Katihar District Katihar District Is One Among 38 Districts of Bihar State ,India

About Katihar District Katihar District is one among 38 Districts of Bihar State ,India. Katihar District Administrative head quarter is Katihar. It is is Located 285 KM west towards State capital Patna . Katihar District population is 3068149. It is 14 th Largest District in the State by population. Geography and Climate Katihar District It is Located at Latitude-25.5, Longitude-87.5. Katihar District is sharing border with Bhagalpur District to the west , Purnia District to the North , Sahebganj District to the South , Maldah District to the South . It is sharing Border with Jharkhand State to the South , West Bengal State to the South . Katihar District occupies an area of approximately 3056 square kilometres. Its in the 37 meters to 31 meters elevation range.This District belongs to Hindi Belt India . Climate of Katihar District It is Hot in summer. Katihar District summer highest day temperature is in between 29 ° C to 44° C . Average temperatures of January is 16 ° C , February is 21 ° C , March is 27 ° C , April is 32 ° C , May is 33 ° C . DemoGraphics of Katihar District Maithili is the Local Language here. Also People Speaks Hindi, Urdu, Bengali And Surjapuri . Katihar District is divided into 16 Blocks , 238 Panchayats , 1174 Villages. Hasanganj Block is the Smallest Block by population with 42886 population. Kadwa Block is the Biggest Block by population with 268917 population. Major producing Items,Crops,Industries and Exports from Katihar District Basket, Jute, JuteItems, LeatherShoes, Makhana, MilkProduct, Rice are the major producing Items and Exports from here. Census 2011 of Katihar District Katihar district Total population is 3068149 according to census 2011.Males are 1601330 and Females are 1466819 .Literate people are 2029887 among total.Its total area is 3056 km². -

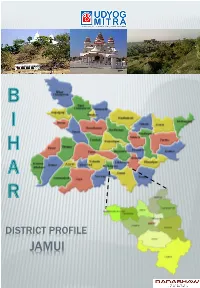

District Profile Jamui Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE JAMUI INTRODUCTION Jamui district is one of the thirty-eight administrative districts of Bihar. The district was formed on 21 February 1991, when it was separated from Munger district. Jamui district is a part of Munger Commissionery. Jamui district is surrounded by the districts of Munger, Nawada, Banka and Lakhisarai and districts Giridih and Deoghar of Jharkhand state. The major rivers flowing in the district are Kiul, Burnar, Sukhnar, Nagi, Nakti, Ulai, Anjan, Ajay and Bunbuni HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Jamui has a glorious history. Historical existence of Jamui has been observed during the Mahabharta period. Jamui was earlier known as Jambhiyaagram. The old name of Jamui has been traced as Jambhubani in a copper plate kept in Patna Musuem. According to Jainism, the 24th Tirthankar Lord Mahavir got divine knowledge in Jambhiyagram/ Jrimbhikgram situated on the bank of river Jambhiyagram Ujjhuvaliya/ Rijuvalika. Hindi translation of the words Jambhiya and Jrimbhikgram is Jamuhi which developed in the recent time as Jamui and the river Ujhuvaliya/ Rijuvalika changed to river Ulai . Jamui was ruled by the Gupta, Pala and Chandel rulers. Indpai is supposed to be the capital of Indradyumna, the last local king of Pala dynasty during the 12th century. It was earlier known as Indraprastha. Many archaeological evidences have been found at this place. Gidhaur, also known as Patsanda, is a small town in Jamui district. It was one of the 568 Princely States in India before the partition of British India in 1947. Kings of Chandel descent belonging to Mahoba of Bundelkhand region, ruled here for more than six centuries. -

Bihar. Area - 30.50 Ha (File No

Kamaljeet Singh, tns STATE LDVEL ENVIRONMI'NT Nlember Secretary IMPACT ASSESSMEN'I SEIAA" Bihar AUTHORITY, BIHAR LetterNo.- 299 Fatna,Dated- tsitoltg NOTICE A meeting of SEIAA shall be held on Wednesday & Thursday, l6th &. l7th October, 2019" All the F{onourable Members are requested to make it eonvenient to attend the meeting at the venue & time mentioned below: Day :- Wednesday & Thursday Date :- I6th & l7'h octob er,2ol9 Time :- 4:00 PM onward. Venue :- Chairman's Chamber 2nd Floor, Beltron Bhawan, Shastri Nagar, patna-23 Agenda t6-10-2019 (Wednesdav) o the followings:- 1. Sand Mining Project on Falgu river at Alipur Glrat of District- Gaya, State- Bihar, Area - 30.05 Ha (File No" - SIA/1(a)1323/16), Online propos:rl No.: -SAVBRIVIIN/I790212016). 2" Sand Mining Project on Shanti Nagar Ghat (Stretch2 of Block -l l) of District:- Gaya, State:- Bihar. Area - 30.50 Ha (File No. - SIA/l(a) l44l/17), Online Proposal No. : - s rA/B RA{IN I t7 9 2s I 20 | 6',). 3. Sand Mining Project on Bajitpur Ghat (Stretch 4, Block - 2) of District:- Gaya, State:- Bihar, Area - 30 Ha (File No. - SIA/l(a)/439117),, Online proposal No.:- SIA/BR/MIN/I7918/2016)" o 4" SHRI RAM JANAKI MEDICAL COLLEGE AND HOSPITAL, Village:- Narghoghi, Tehsil:- Sarairanian, District:- Samastipur, Bihar Total Plot Area:- 85,652 m2. Total Build-up Area:- 1,74,?titi ? l4 n1' (illl+ No. - slA/t(u)/b9J/l!r)" untino propooal No"r SIA,rBRiTvtISi I I 5 I riSiltf I e)" 5. Sand Mining Project on river Kiul at Kishanpur Sand Ghat of Lakhisarai rdistrict, Area - 23 Ha (Proposal No. -

United Nations Development Program

United Nations Development Program Consultancy 2014 / Report on “Deepening Financial Inclusion” Evidence from Two States December 2014 PREPARED BY SEWA BHARAT 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................................. 10 Two Pager Brief: Financial Literacy Based Financial Inclusion (A Sewa UNDP Initiative) .. 16 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 19 A. Backdrop .............................................................................................................................................. 19 B. Financial Literacy .................................................................................................................................. 19 Financial Literacy as a Tool to Inclusion: .................................................................................................. 19 Study Findings on Financial Literacy: ....................................................................................................... 20 Recommendations on Financial Literacy: ................................................................................................ 22 C. Financial Inclusion ................................................................................................................................ 24 The States:............................................................................................................................................... -

The Impact of Local Contract Teachers on Student Outcomes

Look no farther: The impact of local contract teachers on student outcomes Madhuri Agarwal∗ Ana Balc~aoReisy November 26, 2018 Abstract The increasing number of contract teachers in developing countries has led to concerns about its effect on teacher quality. Contract teachers are in general less trained and qualified. However, they are more likely to be hired from the local community which can positively affect student outcomes by reducing social distance or through better monitoring. This paper provides additional evidence on the difference in the impact of contract and regular civil service teachers looking at the effect of being a local teacher. Using a value-added estimation method, based on data from a unique survey in India, we find that there is not a significant difference in the overall performance of the two types of teacher. However, focusing on contract teachers as an identification strategy, we observe local teachers have a significant and positive impact (0.21 to 0.23 standard deviation) on student learning for grade 6. Keywords: teacher quality, contract teacher, local teacher, developing countries JEL Codes: I21,I28, J45 ∗[email protected] Nova School of Business and Economics, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Campus de Campolide 1099-032 LISBOA,Portugal [email protected] Nova School of Business and Economics, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Campus de Cam- polide 1099-032 LISBOA,Portugal We are grateful to Rukmini Banerji and Wilima Wadhwa for sharing the data and their constant support and guidance. We would like to thank Martina Viarengo and Chitra Jogani for their valuable suggestions during the 2018 Development Economics and Policy conference in Zurich and Eric Hanushek for impotant comments during the 4th LEER Conference on Education Economics, Leuven. -

Bodh Gaya 70-80

IPP217, v2 Social Assessment Including Social Inclusion A study in the selected districts of Bihar Public Disclosure Authorized (Phase II report) Public Disclosure Authorized Rajeshwar Mishra Public Disclosure Authorized ASIAN DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH INSTITUTE Public Disclosure Authorized PATNA OFFICE : BSIDC COLONY, OFF BORING PATLIPUTRA ROAD, PATNA - 800 013 PHONE : 2265649, 2267773, 2272745 FAX : 0612 - 2267102, E-MAIL : [email protected] RANCHI OFFICE : ROAD NO. 2, HOUSE NO. 219-C, ASHOK NAGAR, RANCHI- 834 002. TEL: 0651-2241509 1 2 PREFACE Following the completion of the first phase of the social assessment study and its sharing with the BRLP and World Bank team, on February 1, 2007 consultation at the BRLP office, we picked up the feedback and observations to be used for the second phase of study covering three more districts of Purnia, Muzaffarpur and Madhubani. Happily, the findings of the first phase of the study covering Nalanada,Gaya and Khagaria were widely appreciated and we decided to use the same approach and tools for the second phase as was used for the first phase. As per the ToR a detailed Tribal Development Project (TDP) was mandated for the district with substantial tribal population. Purnia happens to be the only district, among the three short listed districts, with substantial tribal (Santhal) population. Accordingly, we undertook and completed a TDP and shared the same with BRLP and the World Bank expert Ms.Vara Lakshnmi. The TDP was minutely analyzed and discussed with Vara, Archana and the ADRI team. Subsequently, the electronic version of the TDP has been finalized and submitted to Ms.Vara Lakshmi for expediting the processing of the same. -

Business Plan for Makhana Clusters in Bihar

Business Plan for Makhana Clusters in Bihar 1 INDEX BUSINESS PLAN FOR MAKHANA CLUSTERS IN BIHAR .................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 4 Botany ......................................................................................................................... 8 Distribution and Habitat ............................................................................................. 9 Nutritional Value ...................................................................................................... 10 Uses ........................................................................................................................... 10 Cultivation and Harvesting of Makhana................................................................... 10 Processing of Makhana............................................................................................. 11 OBJECTIVE ..................................................................................................................... 12 APPROACH & METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................... 13 MAKHANA SECTOR ........................................................................................................ 18 CLUSTER MAPPING.................................................................................................... 19 CLUSTER DIAGRAM ......................................................................................................