List Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12933 Black & Red Sponsor Guide – 2020.Indd

Black & Red Sponsorship Opportunities Saturday, January 25, 2020 | The Bushnell | Hartford, Connecticut Proceeds from the Black & Red to benefit the Digestive Disease Center at Hartford Hospital Sponsorship Deadline: Friday, December 13, 2019 2020 Black & Red Beneficiary Digestive Disease Center at Hartford Hospital An estimated 60 to 70 million people in the United States suffer from digestive disorders, which include a wide spectrum of conditions that affect the esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, and small and large intestine. The causes of these disorders range from infections, inflammatory conditions, to cancer. While some digestive disorders can be solved with simple lifestyle changes, chronic conditions like Crohn’s disease and life-threatening illnesses like colorectal and other gastrointestinal (GI) tract cancers require lifelong management, resulting in thousands of physician and emergency room visits in Connecticut annually. In the United States there are over 15 million emergency department visits and 3 million hospital admissions for patients with GI disease. Expenditures for GI diseases total $135.9 million annually—greater than for other common diseases such as heart disease. Hartford HealthCare is elevating excellence in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders that affect the GI tract with the advancement of the Digestive Disease Center at Hartford Hospital. In partnership with one of the largest gastroenterology practices in the nation, Connecticut GI, the Hartford Hospital Digestive Disease Center specializes in advanced diagnostic and therapeutic interventions to provide high-quality, leading-edge disease treatment. To ensure that patients with GI disorders receive the best possible experience, our physicians collaborate across multiple disciplines, including gastroenterology, surgery, nutrition, oncology, radiology, and pathology. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 19Th December, 2016 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 19th December, 2016 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA Starboy 1 The Weeknd | UMA starboy Rockabye The Weeknd ft. Daft Punk | UMA 2 Clean Bandit | WMA Say You Won't Let Go 3 James Arthur | SME Riding the year out at #1 on the Artist Top 50 is The Weeknd’s undeniable hit Starboy ft. Daft Punk. Black Beatles Overtaking Clean Bandit’s Rockabye ft. Sean Paul & Anne-Marie which now sits at #2, Starboy has 4 Rae Sremmurd | UMA stuck it out and finally taken the crown. Vying for #1 since the very first issue of the Australian Singles Scars to your beautiful Report and published Artist Top 50, Starboy’s peak at #1 isn’t as clear cut as previous chart toppers. 5 Alessia Cara | UMA Capsize The biggest push for Starboy has always come from Spotify. Now on its eighth week topping the 6 Frenship | SME streaming service’s Australian chart, the rest of the music platforms have finally followed suit.Starboy Don't Wanna Know 7 Maroon 5 | UMA holds its peak at #2 on the iTunes chart as well as the Hot 100. With no shared #1 across either Starvi n g platforms, it’s been given a rare opportunity to rise. 8 Hailee Steinfeld | UMA Last week’s #1, Rockabye, is still #1 on the iTunes chart and #2 on Spotify, but has dropped to #5 on after the afterparty 9 Charli XCX | WMA the Hot 100. It’s still unclear whether there will be one definitive ‘summer anthem’ that makes itself Catch 22 known over the Christmas break. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 13Th February, 2017 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 13th February, 2017 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA Shape of you 1 Ed Sheeran | WMA Shape of you Castle on the hill Ed Sheeran | WMA 2 Ed Sheeran | WMA Chameleon 3 PNAU | ETC/UMA Ed Sheeran’s Shape Of You and Castle On The Hill still occupy the Top 2 of the Artist Top 50, with adore Shape Of You still coming out ahead in their tug-of-war for a third week straight. This comes as no 4 Amy Shark | SME surprise however as the track still dominates the Hot 100, Spotify and iTunes charts. issues 5 Julia Michaels | UMA Dance duo PNAU make the first big move at #3 from #26 with hit Chameleon, taking a new peak. Stranger New peaks in the Top 5 are also seen from Amy Shark’s Adore at #4 from #29 and Julia Michael’s 6 Peking Duk | SME debut hit Issues at #5 from #16. paris 7 The Chainsmokers | SME The first and only debut in the Top 20 occurs right at the end of the lower bracket with Major Lazer’s now and later new single Run Up ft. PARTYNEXTDOOR & Nicki Minaj entering the chart at #20. 8 Sage The Gemini | WMA i don't wanna live forever 9 ZAYN & Taylor Swift | UMA cocoon 10 Milky Chance | UMA capsize #1 MOST ADDED TO RADIO 11 Frenship | SME fresh eyes You Say When 12 Andy Grammer | MUSH Illy ft. Marko Penn | ONETWO sexual 13 Neiked | UMA 14 Touch Australia hip-hop staple Illy is this week’s #1 Most Added To Radio with track You Say When ft. -

TIMES SQUARE NEW YEAR's EVE CONTACT: Rubenstein Kyle Sklerov

FROM: TIMES SQUARE NEW YEAR’S EVE CONTACT: Rubenstein Kyle Sklerov (212) 843-8486 or [email protected] Kristen Bothwell (212) 843-9227 or [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Multi-Platinum Pop Singer and Songwriter Andy Grammer to Headline Musical Lineup for Times Square New Year’s Eve Live, Commercial-Free Webcast and TV Pool Feed Grammer to Perform John Lennon’s “Imagine” and Hit Singles "Honey, I'm Good", "Good To Be Alive", "Smoke Clears" and "Fresh Eyes” Country Music Singer-Songwriter Lauren Alaina to Perform Her No. 1 Hits “Road Less Traveled” and “What Ifs” Plus Katy Perry’s “Firework” LA-Based Dance Crew Kinjaz to Perform Webcast Available to Embed for Digital Media Outlets, Bloggers, Social Media Editors, Webmasters, and More NEW YORK - December 18, 2017- Times Square Alliance and Countdown Entertainment, co-organizers of New Year’s Eve in Times Square, today announced that pop music sensation Andy Grammer will headline the live Times Square New Year’s Eve commercial-free webcast and TV pool feed. Country music singer-songwriter Lauren Alaina will also perform on the webcast and TV pool, which features an array of performances, interviews and original content from the center of the festivities in Times Square. In addition to the musical performances, Allison Hagendorf, Global Head of Rock at Spotify, network television host, and Live Announcer of the MTV Video Music Awards and MTV Movie Awards, will return for her sixth year as the Times Square New Year’s Eve Event Host. Jonathan Bennett, star of Mean Girls and host of Cake Wars, will return as the host of the Webcast for the second year. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Contact: Lori Russo, (202) 650-0727, [email protected] Alex Pribilovics, (703) 399-2905, [email protected] The Leukemia Ball, Presented by PhRMA, Celebrating 30th Anniversary, to Feature Blockbuster Entertainment from Comedian Jim Gaffigan and Pop Superstar Andy Grammer PhRMA Continues Long-Term Presenting Sponsorship December 12, 2016 (Washington, DC) – Celebrating its 30th year as one of the Washington area’s most prominent charity events, the Leukemia Ball, presented by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) will be held Saturday, March 11, 2017, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Since the first Leukemia Ball in 1987, the event has raised more than $52 million and continues to dedicate efforts to raising money for life-saving cancer research and patient programs funded by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS). PhRMA, the trade association representing the country’s leading innovative biopharmaceutical research companies, is continuing its presenting sponsorship. “PhRMA is proud to continue our partnership with LLS to further its mission of improving the outlook for cancer patients and their families, particularly in this milestone year for the Leukemia Ball,” said Stephen J. Ubl, president and chief executive officer, PhRMA. “Together, we are dedicated to finding new treatments and cures for cancer patients. Significant advances in recent years give us hope that we are closer than ever to a world without blood cancers.” Guests at the 2017 gala will enjoy entertainment from actor, New York Times bestselling author and Grammy nominated comedian Jim Gaffigan, known for his family-focused “clean” comedy. In 2015, Gaffigan became one of only ten comedians in history to sell out the famed Madison Square Garden arena for the finale of his "Contagious" tour, he opened for Pope Francis in front of more than one million people in Philadelphia, and his television show, "The Jim Gaffigan Show," debuted on TV Land to enormous ratings and reviews. -

Alive@Five and Wednesday Nite Live Begins This Week

For immediate release Contact: Annette Einhorn, 203/348-5285 [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORY: TO APPLY FOR MEDIA CREDENTIALS FOR FUTURE ALIVE@FIVE OR WEDNESDAY NITE LIVE 2019, ACCREDITED MEDIA MUST APPLY BY JULY 12 AT THE FOLLOWING LINK: DEADLINE HAS PASSED FOR THIS WEEK. http://stamford-downtown.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2019-ALIVE@FIVE-WNL-MEDIA- APPLICATION_FORM.pdf STAMFORD DOWNTOWN PRESENTS WEDNESDAY NITE LIVE SUMMER CONCERT SERIES (BEGINS JULY 10) ALIVE@FIVE (BEGINS THURSDAY, JULY 11) Wednesday Nite Live Concerts Wed., July 10 through August 7, 2019 Alive@Five Concerts Thursdays, July 11 through August 8, 2019 STAMFORD DOWNTOWN, Conn., July 8, 2019 – Two of the region’s hottest concert series, Morgan Stanley presents Wednesday Nite Live in partnership with BDO USA and City Carting & Recycling on the Dental365 Stage and Alive@Five in partnership with Reckson and BevMax on the Dental365 Stage and kick off on Wednesday, July 10 and Thursday, July 11 respectively in Columbus Park in Stamford Downtown. Morgan Stanley presents Wednesday Nite Live in partnership with BDO USA and City Carting & Recycling on the Dental365 Stage kicks off Wednesday, July 10 in Columbus Park in Stamford Downtown. The five-week long series runs Wednesdays, July 10 through August 7 in Columbus Park at 6:30 pm. All ages will be admitted to Wednesday Nite Live. $20 Entrance Fee, 12 and under free with paid adult. For more information and a complete list of rules and restricted items please visit: www.stamford-downtown.com/events July 10 Andy Grammer Multi-platinum selling pop artist Andy Grammer is all about inspiring and empowering the world by communicating his truths through his music. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Contact: Lori Russo, (202) 650-0727, [email protected] Alex Pribilovics, (703) 399-2905, [email protected] The Leukemia Ball, Presented by PhRMA, Celebrating 30th Anniversary, to Feature Blockbuster Entertainment from Comedian Jim Gaffigan and Pop Superstar Andy Grammer PhRMA Continues Long-Term Presenting Sponsorship December 12, 2017 (Washington, DC) – Celebrating its 30th year as one of the Washington area’s most prominent charity events, the Leukemia Ball, presented by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) will be held Saturday, March 11, 2017, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Since the first Leukemia Ball in 1987, the event has raised more than $52 million and continues to dedicate efforts to raising money for life-saving cancer research and patient programs funded by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS). PhRMA, the trade association representing the country’s leading innovative biopharmaceutical research companies, is continuing its presenting sponsorship. “PhRMA is proud to continue our partnership with LLS to further its mission of improving the outlook for cancer patients and their families, particularly in this milestone year for the Leukemia Ball,” said Stephen J. Ubl, president and chief executive officer, PhRMA. “Together, we are dedicated to finding new treatments and cures for cancer patients. Significant advances in recent years give us hope that we are closer than ever to a world without blood cancers.” Guests at the 2017 gala will enjoy entertainment from actor, New York Times bestselling author and Grammy nominated comedian Jim Gaffigan, known for his family-focused “clean” comedy. In 2015, Gaffigan became one of only ten comedians in history to sell out the famed Madison Square Garden arena for the finale of his "Contagious" tour, he opened for Pope Francis in front of more than one million people in Philadelphia, and his television show, "The Jim Gaffigan Show," debuted on TV Land to enormous ratings and reviews. -

Guns N' Roses Entity Partnership Citizenship California Composed Of: W

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA966168 Filing date: 04/10/2019 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Guns N' Roses Entity Partnership Citizenship California Composed Of: W. Axl Rose Saul Hudson Michael "Duff" McKagan Address c/o LL Management Group West, LLC 5950 Canoga Ave., Ste. 510 Woodland Hills, CA 91367 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- Jill M. Pietrini Esq. tion Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP 1901 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600 Los Angeles, CA 90067 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], MDan- [email protected], [email protected], RLHud- [email protected] 310-228-3700 Applicant Information Application No 87947921 Publication date 03/12/2019 Opposition Filing 04/10/2019 Opposition Peri- 04/11/2019 Date od Ends Applicant ALDI Inc. 1200 N. Kirk Road Batavia, IL 60510 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 029. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: cheese, namely, cheddar cheese Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act Section 2(d) False suggestion of a connection with persons, Trademark Act Section 2(a) living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or brings them into contempt, or disrep- ute Mark Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application/ Registra- NONE Application Date NONE tion No. -

Leonard Bernstein

JOHN WILLIAMS LAUREATE CONDUCTOR AMERICA’S FAVORITE ORCHESTRA CELEBRATES AN AMERICAN ICON AT 100 Leonard Bernstein Leonard Bernstein Centennial America’s favorite orchestra celebrates an American icon at 100—Leonard Bernstein! The Boston Pops is thrilled to embark on a season-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of the conductor and composer’s birth in 1918 in Lawrence, MA. Leonard Bernstein’s fifty year association with the BSO began in the summer of 1940, when he became a member of Serge Koussevitzky’s first conducting class at the new Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood and continued throughout the years as he headed up the orchestral and conducting programs at Tanglewood. This season’s concerts include a Centennial Tribute theme throughout featuring his wide variety of works including selections from Candide, West Side Story, On The Town, and many more! OPENING NIGHT AT POPS LEONARD BERNSTEIN DISNEY’S BROADWAY HITS ROCK THE POPS WITH Keith Lockhart, conductor WITH ANDY GRAMMER CENTENNIAL TRIBUTE Saturday, May 12, 3pm* ALFIE BOE Keith Lockhart, conductor Keith Lockhart, conductor Sunday, May 13, 3pm* Keith Lockhart, conductor Wednesday, May 9, 8pm Friday, May 11, 8pm Tuesday, May 15, 8pm For 20 years, Disney has astonished millions Multi-platinum selling pop artist Andy Saturday, May 12, 8pm Wednesday, May 16, 8pm Thursday, May 17, 8pm worldwide with theatrical productions Grammer joins the Pops to perform his series sponsor that both entertain and amaze. In an As we continue to expand our Pops Rock & Roll infectious and empowering -

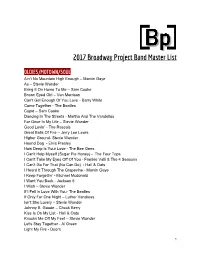

2017 Broadway Project Band Master List

2017 Broadway Project Band Master List OLDIES/MOTOWN/SOUL Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – Marvin Gaye As – Stevie Wonder Bring It On Home To Me – Sam Cooke Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Can't Get Enough Of You Love Barry White - Come Together - The Beatles Cupid – Sam Cooke Dancing In The Streets - Martha And The Vandellas For Once In My Life – Stevie Wonder Good Lovin' The Rascals - Great Balls Of Fire – Jerry Lee Lewis Higher Ground- Stevie Wonder Hound Dog - Elvis Presley How Deep Is Your Love - The Bee Gees I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie Honey) - The Four Tops I Can't Take My Eyes Off Of You - Frankie Valli & The 4 Seasons I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do) - Hall & Oats I Heard It Through The Grapevine - Marvin Gaye I Keep Forgettin’ - Michael Mcdonald I Want You Back - Jackson 5 I Wish – Stevie Wonder If I Fell in Love With You- The Beatles If Only For One Night – Luther Vandross Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder Johnny B. Goode – Chuck Berry Kiss Is On My List - Hall & Oats Knocks Me Off My Feet – Stevie Wonder Let's Stay Together - Al Green Light My Fire - Doors 1 Living In The City – Stevie Wonder Long Trains Running – Doobie Brothers Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett My Cherie Amour – Stevie Wonder My Girl Temptations - Oh What A Night – Frankie Valli Overjoyed – Stevie Wonder Poppas Got A Brand New Bag – James Brown Proud Mary – Tina Turner Respect - Aretha Rock Steady - Aretha Franklin Rosalita – Bruce Springsteen Runaround Sue – Dion Shout – The Isley Brothers Signed Sealed Delivered - Stevie Wonder Sir Duke – Stevie Wonder Sittin' -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 27Th March, 2017 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 27th March, 2017 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA shape of you 1 Ed Sheeran | WMA shape of you something just like this Ed Sheeran | WMA 2 The Chainsmokers & Coldp... castle on the hill 3 Ed Sheeran | WMA Ed Sheeran’s Shape Of You is dominant for another week on the Artist Top 50 while The chained to the rhythm Chainsmokers & Coldplay’s Something Just Like This doesn’t budge from #2. Away from the 4 Katy Perry | EMI expected Sheeran/Chainsmokers/Coldplay shootout at the top of the chart, Jon Bellion makes all time low serious gains with All Time Low at #5. 5 Jon Bellion | EMI i don't wanna live forever A new peak for the track, and for Bellion on the chart, it’s making the most of what has shaped up to 6 ZAYN & Taylor Swift | UMA be a slow burner of a promotion cycle. Released late last year, the track only started to get traction in slide 7 Calvin Harris | SME recent months. Since then it’s made its way across all of commercial radio with a healthy amount of green light spins on all fronts. Its performance on digital should be taken into account here too – the Australian 8 Lorde | UMA Spotify Chart shows Bellion cracking #13 from #21 and trending upwards, also taking #13 on the don't leave iTunes chart up from #14. 9 Snakehips | SME water under the bridge 10 Adele | RC/INERTIA Touch #1 MOST ADDED TO RADIO 11 Little Mix | SME scared to be lonely symphony 12 Martin Garrix | SME Clean Bandit ft. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 6Th February, 2017 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 6th February, 2017 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA Shape of you 1 Ed Sheeran | WMA Shape of you Castle on the hill Ed Sheeran | WMA 2 Ed Sheeran | WMA fresh eyes 3 Andy Grammer | MUSH Ed Sheeran’s Shape Of You still holds #1 on the Artist Top 50 after overtaking his other hit Castle On Stranger The Hill last week. With Sheeran keeping the Top 2, the first new movers make themselves known 4 Peking Duk | SME further down the Top 10. paris 5 The Chainsmokers | SME Taking #3 from #4 and earning a new peak is Andy Grammer’s Fresh Eyes. It leads ahead of Peking now and later Duk’s Stranger, now at #4 from #22, also a new peak, which in turn beats out The Chainsmokers’ Paris, 6 Sage The Gemini | WMA now at #5 from #20. Sage The Gemini’s Now And Later is the last of this trend in the Top 10, now at i don't wanna live forever 7 ZAYN & Taylor Swift | UMA #6 from #16 on its third week in the chart. 8 sexual Snakehips’ Don’t Leave cracks the Top 20 at #13 from #42, as does Little Mix’s Touch at #14 from #27, Neiked | UMA and Julia Michaels’ Issues at #16 from #29, its debut point. The last track to enter the top bracket is 24k Magic 9 Bruno Mars | WMA Machine Gun Kelly & Camila Cabello’s Bad Things at #19 from #21.