Reformist Politicians Drive Basel Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFRICA RISK CONSULTING Ghana Monthly Briefing December 2020

AFRICA RISK CONSULTING Ghana Monthly Briefing December 2020 Ghana Summary 17 December 2020 President Nana Addo Akufo-Addo (2017-present) secures a second four-year term in a tight presidential election but without a majority in parliament and his opponent, former President John Mahama (2012-2017), refusing to concede defeat. Economists are divided in opinion on how the current uncertain political environment will impact economic activity and local and foreign investment in the country. The election was largely peaceful but marred by patches of violence during counting and collation of results, with six recorded election-related deaths. Akufo Addo wins re-election, opposition claims fraud Ghana’s Electoral Commission (EC) announced on 9 December that President Nana Akufo-Addo (2017-present) of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) had secured 51.59% of the valid votes cast in presidential polls held on 7 December, beating his opponent and predecessor, former President John Mahama (2012-2017) of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) who obtained 47.366%.1 Mahama has rejected the election results, describing them as “fraudulent”, and has vowed to take up a legal battle. ARC’s sources in Ghana say there is a tense atmosphere in the country as the nation awaits the next move by the opposition NDC – although the election was largely peaceful. The two major parties failed to gain an absolute majority in the country’s 275-seat parliament, with the NDC wiping out of the NPP’s 63-seat majority. The ECC announced on 17 December that the NDC won the remaining seat to be counted in the legislative elections, Sene West, matching the ruling party’s tally and creating a hung parliament. -

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

Download Date 28/09/2021 19:08:59

Ghana: From fragility to resilience? Understanding the formation of a new political settlement from a critical political economy perspective Item Type Thesis Authors Ruppel, Julia Franziska Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 28/09/2021 19:08:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/15062 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. GHANA: FROM FRAGILITY TO RESILIENCE? J.F. RUPPEL PHD 2015 Ghana: From fragility to resilience? Understanding the formation of a new political settlement from a critical political economy perspective Julia Franziska RUPPEL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities University of Bradford 2015 GHANA: FROM FRAGILITY TO RESILIENCE? UNDERSTANDING THE FORMATION OF A NEW POLITICAL SETTLEMENT FROM A CRITICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY PERSPECTIVE Julia Franziska RUPPEL ABSTRACT Keywords: Critical political economy; electoral politics; Ghana; political settle- ment; power relations; social change; statebuilding and state formation During the late 1970s Ghana was described as a collapsed and failed state. In contrast, today it is hailed internationally as beacon of democracy and stability in West Africa. -

The Rural Banker Issue 4 Q4, 2018

THE RURAL BANKER ISSUE 4 Q4, 2018 FEATURED BANKS Bongo Builsa Fiaseman BIENNIAL GENERAL MEETING HELD AT BOLGATANGA Comfort Owusu The first female Executive Director of the Association of Rural Banks EDUCARE PLAN The perfect support for your child’s education! @PhoenixLifeSocial Issue The Rural Banker 4 CONTENTS 15 The genesis of Rural Banking in Ghana. 12 HOW BONGO RURAL BANK IS CHANGING LIVES IN 18 PROFITS ARE SOARING AT BUILSA COMMUNITY OnJuly9, 1976,the first Rural Bank was born THE UPPER EAST REGION BANK, MAKING IT AN INDUSTRY BENCHMARK at Agona Nyakrom. Dr Sam Dufu was the first Chairman of the Board of Directors... Bongo Rural Bank Hayatudeen Awudu 37 Upper East Regional Minister woos (BORBA) Limited, is one Ibrahim became investors. of the most progressive General Manager of The Regional Minister made the call during and thriving Rural Banks Builsa Community Bank the 20th Biennial General Meeting of the in the Upper East Region. (Bucobank) in 2012. Association of Rural Banks ARB-Ghana... Established at Bongo in Hayat as he is affectionately 2009, it presently has called, joined Bucobank on three Mobilization Centres July 1, 2005 initially as a 38 Quotes from the Chapter Presidents. at Namoo, Soe, and The Rural Banker interacted with Chief Clerk. He rose Zorkor, all in the Upper through the ranks to some Chapter Presidents of the East Region... Association of Rural Banks (ARB) on the position of General the sidelines of the recently held... Manager. 45 Procrastination: a scientific guide on how to stop it. Procrastination is a challenge we have all faced at one point or another. -

Market Review 1St Quarter, 2017 Pent Assets

Market Review 1st Quarter, 2017 Pent Assets Economy The first quarter (Q1) of 2017 was an eventful one with The currency also lost 3.7 percent and 3.9 percent to activities including the swearing-in ceremony of the British Pound and Euro, respectively. Ghana’s new government as well as reading of the Interbank Foreign Exchange government’s first budget statement. The budget, Q1 Change (%) YTD Chg. (%) which primarily signals expansionary fiscal policy, seeks USD/GHS 4.3173 -2.7% (DPN) -2.7% (DPN) to grow gross domestic product (GDP) to 6.3 percent GBP/GHS 5.3964 -3.7% (DPN) -3.7% (DPN) and reduce overall fiscal deficit to 6.5 percent of GDP EUR/GHS 4.6164 -3.9% (DPN) -3.9% (DPN) in 2017 through tax cuts. Ghana’s GDP and overall fiscal deficit stood at 3.6 percent and 10.3 percent respectively in 2016, according to provisional figures. Treasury Securities Market Development of yields on government of Ghana The quarter also saw a monetary policy boost to treasury securities was generally mixed. The yield on growth. The Bank of Ghana through its Monetary 91-day treasury bill rose 108 basis points during the Policy Committee lowered the benchmark policy rate quarter to close at 17.51 percent, yield on 182-day bill by 200 basis points to 23.5 percent. The bank’s fell by to 45 basis points to 17.19 percent and yield on decision was primarily influenced by improved inflation 1-year treasury note fell by 200 basis points to 19.00 outlook and growth concerns. -

EDITION 411.Cdr

EDITION. Et0411 MONDAY 11 JUN. - SUNDAY 17 JUN. 2018 MiDA rolls out Energy Efficiency activities under Compact II EDITION: Et0411 MONDAY 11 JUN. - SUNDAY 17 JUN. 2018. Reliable Indepth Informative GHC 2.00 / US$ 1.00 he Millennium Development initiatives seek to address the Authority (MiDA), Ghana, is constraints to the supply of adequate Mobile money now biggest Ts e t t o r o l l o u t v a r i o u s and reliable power, while the EEDSM programmes under its Energy project would signicantly reduce E f c i e n c y a n d D e m a n d S i d e peak demand, ensure adequate non-cash payment platform Management (EEDSM) project, all supply for all and reduce investments aimed at ensuring energy efciency needed in expensive additional ...more mobile money payments and conservation. generation facilities. The EEDSM Project, a component The EEDSM, one of the six projects under the Ghana Power Compact, making up the Compact II, is expected than cheques, debit cards etc. also known as Compact II, has been t o i m p l e m e n t s e v e r a l p o l i c y By Elorm Desewu 2017. The number of mobile increase to 23,947,437 in designed to directly support Ghana's initiatives and programmes that money accounts increased to December 2017 compared with sector strategic objectives to achieve would ensure energy efciency and he latest report on 23.9 million in 2017 compared 19,735,098 in December of the power supply sufciency, including conservation among Ghanaians. -

FCAB Africa the Launch of a Multinational Collaboration July 15, 2021

FCAB Africa The Launch of a Multinational Collaboration July 15, 2021 AN EVENT OF THE 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Consortium for Social Development Hosted by the University of Johannesburg Livestream the FCAB Africa launch event! https://twitter.com/i/broadcasts/1gqxvolDdeWKB https://www.facebook.com/csda.uj/live_videos/ https://unc.zoom.us/j/92755730932 Contact Dr. David Ansong Dr. Moses Okumu Center for Social Development School of Social Work School of Social Work Washington University University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] csd.wustl.edu/FCABAfrica An Overview of FCAB Africa Financial Capability and Asset Building in Africa (FCAB Africa) is a strategic partnership among a diverse set of university researchers, social-work and human-service practitioners, financial-service providers, policymakers, and donors. The initiative aims to increase financial capability and asset holding in order to improve financial stability and security of socially and financially marginalized populations in Africa, thereby strengthening their social and economic well-being. The initiative will achieve this goal by equipping frontline human-service practitioners with basic financial knowledge and skills for their work with marginalized populations. Social workers, community-development practitioners, health-care providers, teachers, counselors, and other human- service professionals regularly serve such populations, which may benefit from financial guidance and coaching. The initiative will also work with financial-service providers to create a comprehensive financial-development program delivered through existing services, including fintech. The FCAB Africa initiative is led by Dr. David Ansong (School of Social Work, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) and Dr. -

Special Report on Unibank

Ethiopia: Abiy Ahmed’s big gamble South Sudan: Another chance at peace AfricThe pan-Africana magazinew of achoice tch Ghana Travesty of justice How dirty politics killed uniBank to bring Kwabena Duffuor down Ken Ofori-Atta Ghana’s economic ‘magician’ who got away with fraud Coronavirus pandemic Africa takes a hit JUNE/JULY 2020 United States: $6.00 l Canada: C$6.50 l UK: £5.00 l Euro Zone: €5.50 l South Africa: R50.00 l Nigeria: N1000 l Ethiopia: Br100.0 l Kenya: KShs350 l Ghana: GH¢12.00 Special RepoRt Ghana TRAVESTY OF JUSTICE How dirty politics killed uniBank Special RepoRt uniBank The tragedy of uniBank ... and the targeting of Dr. Kwabena Duffuor A branch of uniBank Ghana which was closed down by the government on August 1, 2018. ot many people know about the dirty behind- Ministry of Finance regarding these actions. In that bombshell the-scenes politics that led to the collapse letter, Ofori Atta’s subordinates were instructed to keep its in August 2018 of one of Ghana’s largest contents “under wraps” – but it leaked nonetheless. indigenous banks, uniBank. A bank that had What is worse: The government could have saved uniBank if it been going strong for the previous 16 years, wanted, but clearly chose not to. uniBank’s troubles began only 7 months Without even using taxpayers’ resources, the government could after President Nana Akufo-Addo came to have stopped uniBank from going under by simply paying the bank power in 2017. Just a year later the bank about GH¢1.0bn that the government and its related entities was dead, killed through an orchestrated and combined action by already owed uniBank. -

Bank of Ghana Annual Report 2009

BANK OF GHANA ANNUAL REPORT 2009 2009 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS PAGE SECTION II FOREWORD BY THE GOVERNOR IV MANAGEMENT OF THE BANK V ORGANISATIONAL CHART 01 1.0 Governance 29 5.0 Internal Developments 1.1 The Board of Directors 5.1 Overview 1.2 Committees of the Board 5.2 Centre for Training and Professional 1.3 Reconstitution of the Board Development 1.4 Appointment of the Advisory Panel 5.3 Human Resource Activities 1.5 The Monetary Policy Committee 5.4 Regional Operations 5.5 Collateral Registry 05 2.0 Developments in The Global Economy 5.6 Sporting Activities 2.1 World Output Growth 2.2 Unemployment 31 6.0 External Relations 2.3 General Price Level 6.1 Overview 2.4 Monetary Policy Stance and Interest Rates 6.2 International Monetary Fund 2.5 Foreign Exchange Market Developments and the World Bank 2.6 Commodities Market 6.3 West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ) 2.7 Developments in Major Capital Markets 6.4 West African Monetary Agency (WAMA) 2.8 Outlook for 2010 6.5 West African Institute of Financial and Economic Management 09 3.0 Developments in the Ghanaian Economy 6.7 African Export-Import Bank 3.1 Overview (AFREXIMBANK) 3.2 Monetary Policy 6.8 Visit by the Governor of 3.3 Monetary Developments the Central Bank of Nigeria 3.4 Interest Rates Developments 3.5 Price Developments 37 7.0 Financial Statements 3.6 Real Sector Performance Corporate Information 3.7 Fiscal Developments Report of the Directors 3.8 External Sector Developments Independent Auditor’s Report 3.9 External Debt Statements of Financial Position 3.10 Stock Market Developments -

The Political Economy of Bank Regulation in Developing Countries OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/02/20, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/02/20, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/02/20, SPi The Political Economy of Bank Regulation in Developing Countries OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/02/20, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/02/20, SPi The Political Economy of Bank Regulation in Developing Countries Risk and Reputation Edited by EMILY JONES 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/02/20, SPi 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2020 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2020 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947029 ISBN 978–0–19–884199–9 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198841999.003.0001 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. -

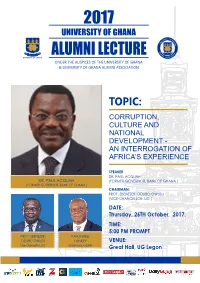

Please Click Here to Access the Event Brochure

2017 UNIVERSITY OF GHANA ALUMNI LECTURE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA & UNIVERSITY OF GHANA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION TOPIC: CORRUPTION, CULTURE AND NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT - AN INTERROGATION OF AFRICA’S EXPERIENCE SPEAKER DR. PAUL ACQUAH DR. PAUL ACQUAH (FORMER GOVERNOR, BANK OF GHANA ) ( FORMER GOVERNOR, BANK OF GHANA ) CHAIRMAN: PROF. EBENEZER ODURO OWUSU (VICE-CHANCELLOR, UG ) DATE: Thursday, 26TH October, 2017. TIME: 5:00 PM PROMPT PROF. EBENEZER PAA KWESI ODURO OWUSU YANKEY VENUE: Vice-Chancellor, UG Chairman, UGAA Great Hall, UG Legon DR. PAUL AMOAFO ACQUAH 2017 ALUMNI LECTURE 1 PROFILE DR. PAUL AMOAFO ACQUAH Dr. Paul Amoafo Acquah is a former Governor of the Bank of Ghana. He served for two four-year terms ending September 2009 and as the Chairman of the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee. He was Chairman of the Committee of Governors of the Central Banks of Ecowas Member States from 2005 to 2008 under the Regional Monetary Integration and Cooperation arrangement. He served as a member of the Principles Consulting Group for the Principles of Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring in Emerging Markets established under the Institute of International Finance (IFF), Washington, DC. He was also a member of an expert group of External Advisors appointed for the study on structural policy issues for the 2014 Triennial Review of Surveillance (IMF). Prior to his appointment as Governor, Dr. Acquah was Deputy Director in the African Department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He exercised responsibility for, and general oversight of operational work on African countries, including policy advice and program design, and relations with institutions and donors and creditors. -

WEEKLY FINANCIAL MARKET REPORT SUMMARY from 27TH- 31St MARCH, 2017

WEEKLY FINANCIAL MARKET REPORT SUMMARY FROM 27TH- 31st MARCH, 2017 TEL: +233(0) 302798704/ 307034122 EMAIL: [email protected] MACROECONOMIC INDICATORS NEWS HEADLINES BOG REDUCES POLICY RATE TO 23.5% Index 2016 Close (%) Previous (%) Current (%) Change (%) The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of Ghana has reduced the Inflation(CPI) 15.40 13.30 13.20 -0.10 policy rate to 23.5%. This represents a 200 basis point reduction from the Policy Rate 25.50 25.50 23.50 -2.00 previous figure of 25.5%. Governor of the Central bank, Dr. Abdul Nashiru Issahaku disclosed this at the press briefing to conclude the second MPC meeting for 2017. Dr. Issahaku cited the declining inflation among others as MACROECONOMIC TARGETS FOR 2017 reasons for the drop in the policy rate. This is the second time that the MPC has reduced the policy rate after keeping it unchanged at 26% for a greater Index (%) part of 2016. The policy rate is the rate at which commercial banks borrow Overall Real GDP(Including Oil) Growth 6.30 from the central bank for onward lending to their customers. Non- Oil Real GDP Growth 4.20 http://citibusinessnews.com/ An End of Year Inflation Target 11.20 BOG GOVERNOR RESIGNS The Central Bank Governor, Dr. Abdul Nashiru Issahaku has resigned. Sources have gathered his resignation took effect from the 1st of April, 2017. GOG TREASURY BILL RATES It’s unclear what led to his resignation but the Governor is reported to have Fixed Income Previous Week (%) Current Week (%) Change (%) cited personal reasons for the move.