The Ethereal System: Ambience As a New Musical Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Bibliographie Stockhausen 1952-2013 Engl

Stockhausen-Bibliography 1952-2013 [June 2013] The following bibliography alphabetically lists the authors who have written secondary literature about Karlheinz Stockhausen’s oeuvre: monographs, articles in books, periodicals and dictionaries, comprehensive works in which Stockhausen’s oeuvre is examined in detail. Reviews, contributions to concert programmes and publications in daily and weekly newspapers are only mentioned if they are considered to have reference value. Stockhausen’s own texts are not included, and conversations and interviews are only partly listed. Several works by the same author are listed consecutively in chronological order. When the name of the author was not available, the titel was listed alphabetically. This list includes the bibliographies that were published in Texte zur Musik, Vol. 6 (compiled by Chr. von Blumröder and H. Henck) and Vol. 10 (Chr. von Blumröder, R. Sengstock, D. Schwerdtfeger), and was supplemented and up-dated until 2013 (M. Luckas, I. Misch). Abkürzungen und Siglen / Abbreviations and Sigla AfMw. Archiv für Musikwissenschaft / Archive for Musicology Aufl. Auflage / printing Ausg. Ausgabe / edition Bd., Bde Band, Bände / volume, volumes Beitr. Beitrag / contribution BzAfMw. Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft / Supplementary booklets for the Archive for Musicology ders., dies. derselbe, dieselbe / the same DMT Dansk musiktidsskrift dt. deutsch / German eng. englisch / English erw. erweitert / supplemented Ffm. Frankfurt am Main / Frankfurt FP Feedback Papers frz. französisch / French H. Heft / booklet, issue Hbg Hamburg hg. herausgegeben / edited HmT Handwörterbuch der musikalischen Terminologie, hg. v. H. H. Eggebrecht, Wiesbaden 1972–1983, Stuttgart 1984–2006 / Hand Dictionary of Musical Terminology Ins. Institut / Institute jap. japanisch / Japanese Ldn London 1 ML Music and Letters MR The Music Review MT The Musical Times MuB Musik und Bildung Mw. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit N9.2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE ALL THE MUSE TI:AT FITS THE PITCH ISSUE NO. 10 JULY -AUGUST 1981 LeRoi, John CaIe, Stones, Blues, 3 Friends, Musso. Give the gift of music. OIfCharlie Parleer + PAGE 2 THE PENN:Y PITCH mJTU:li:~u-:~u"nU:lmmr;unmmmrnmmrnmmnunrnnlmnunPlIiunnunr'mlnll1urunnllmn broke. Their studio is above the Tomorrow studio. In conclusion, I l;'lish Wendy luck, because l~l~ lPIITC~1 I don't believe in legislating morals. Peace, love, dope, is from the Sex Machine a.k.a. (Dean, Dean) p.S. Put some more records in the $4.49 RELIGIOUS NAPOLEON group! 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Dear Warren: (Dear Sex Machine: Titles are being added to (816) 561-1580 I recently came across something the $4.49 list each month. And at the Moon I thought you might "Religion light Madness Sale (July 17), these records is excellent stuff keeping common will be $3.99! Also, it's good to learn that people quiet." --Napoleon Bonaparte the spirit of t_he late Chet Huntley still can Editor ..............• Charles Chance, Jr. (1769-1821). Keep up the good work. cup of coffee, even one vibrated Assistant Editors ...•. Rev. Frizzell Howard Drake Jay '"lctHUO':V_L,LJLe Canyon, Texas LOVE FINDS LeROI Contributing Writers and Illustrators: (Dear Mr. Drake: I think Warren would Dear Warren: Milton Morris, Sid Musso, DaVINK, Julia join us in saying, "Religion is like This is really a letter to Donk, Richard Van Cleave, Jim poultry-- you gotta pluck it and fry it LeRoi. -

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Sound 1973-78 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Borderline 1974-78 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. In the second half of the 1970s, Brian Eno, Larry Fast, Mickey Hart, Stomu Yamashta and many other musicians blurred the lines between rock and avantgarde. Brian Eno (34), ex-keyboardist for Roxy Music, changed the course of rock music at least three times. The experiment of fusing pop and electronics on Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy (sep 1974 - nov 1974) changed the very notion of what a "pop song" is. Eno took cheap melodies (the kind that are used at the music-hall, on television commercials, by nursery rhymes) and added a strong rhythmic base and counterpoint of synthesizer. The result was similar to the novelty numbers and the "bubblegum" music of the early 1960s, but it had the charisma of sheer post-modernist genius. Eno had invented meta-pop music: avantgarde music that employs elements of pop music. He continued the experiment on Another Green World (aug 1975 - sep 1975), but then changed its perspective on Before And After Science (? 1977 - dec 1977). Here Eno's catchy ditties acquired a sinister quality. -

Russell-Mills-Credits1

Russell Mills 1) Bob Marley: Dreams of Freedom (Ambient Dub translations of Bob Marley in Dub) by Bill Laswell 1997 Island Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance, image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings: Russell Mills 2) The Cocteau Twins: BBC Sessions 1999 Bella Union Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) 3) Gavin Bryars: The Sinking Of The Titanic / Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet 1998 Virgin Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 4) Gigi: Illuminated Audio 2003 Palm Pictures Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Jean Baptiste Mondino 5) Pharoah Sanders and Graham Haynes: With a Heartbeat - full digipak 2003 Gravity Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 6) Hector Zazou: Songs From The Cold Seas 1995 Sony/Columbia Art and design: Russell Mills and Dave Coppenhall (mc2) Design assistance: Maggi Smith and Michael Webster 7) Hugo Largo: Mettle 1989 Land Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance: Dave Coppenhall Photography: Adam Peacock 8) Lori Carson: The Finest Thing - digipak front and back 2004 Meta Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Lori Carson 9) Toru Takemitsu: Riverrun 1991 Virgin Classics Art & design: Russell Mills Cover -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

INTRODUCTION: BLUE NOTES TOWARD a NEW JAZZ DISCOURSE I. Authority and Authenticity in Jazz Historiography Most Books and Article

INTRODUCTION: BLUE NOTES TOWARD A NEW JAZZ DISCOURSE MARK OSTEEN, LOYOLA COLLEGE I. Authority and Authenticity in Jazz Historiography Most books and articles with "jazz" in the title are not simply about music. Instead, their authors generally use jazz music to investigate or promulgate ideas about politics or race (e.g., that jazz exemplifies democratic or American values,* or that jazz epitomizes the history of twentieth-century African Americans); to illustrate a philosophy of art (either a Modernist one or a Romantic one); or to celebrate the music as an expression of broader human traits such as conversa- tion, flexibility, and hybridity (here "improvisation" is generally the touchstone). These explorations of the broader cultural meanings of jazz constitute what is being touted as the New Jazz Studies. This proliferation of the meanings of "jazz" is not a bad thing, and in any case it is probably inevitable, for jazz has been employed as an emblem of every- thing but mere music almost since its inception. As Lawrence Levine demon- strates, in its formative years jazz—with its vitality, its sexual charge, its use of new technologies of reproduction, its sheer noisiness—was for many Americans a symbol of modernity itself (433). It was scandalous, lowdown, classless, obscene, but it was also joyous, irrepressible, and unpretentious. The music was a battlefield on which the forces seeking to preserve European high culture met the upstarts of popular culture who celebrated innovation, speed, and novelty. It 'Crouch writes: "the demands on and respect for the individual in the jazz band put democracy into aesthetic action" (161). -

Sonification As a Means to Generative Music Ian Baxter

Sonification as a means to generative music By: Ian Baxter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts & Humanities Department of Music January 2020 Abstract This thesis examines the use of sonification (the transformation of non-musical data into sound) as a means of creating generative music (algorithmic music which is evolving in real time and is of potentially infinite length). It consists of a portfolio of ten works where the possibilities of sonification as a strategy for creating generative works is examined. As well as exploring the viability of sonification as a compositional strategy toward infinite work, each work in the portfolio aims to explore the notion of how artistic coherency between data and resulting sound is achieved – rejecting the notion that sonification for artistic means leads to the arbitrary linking of data and sound. In the accompanying written commentary the definitions of sonification and generative music are considered, as both are somewhat contested terms requiring operationalisation to correctly contextualise my own work. Having arrived at these definitions each work in the portfolio is documented. For each work, the genesis of the work is considered, the technical composition and operation of the piece (a series of tutorial videos showing each work in operation supplements this section) and finally its position in the portfolio as a whole and relation to the research question is evaluated. The body of work is considered as a whole in relation to the notion of artistic coherency. This is separated into two main themes: the relationship between the underlying nature of the data and the compositional scheme and the coherency between the data and the soundworld generated by each piece. -

Eric Chasalow/Over the Edge New World Records 80440 in Art, One

Eric Chasalow/Over the Edge New World Records 80440 In art, one and one at times make three. In art for the ear, and particularly with acoustic in combination with electronically-created sounds, the listener tends to hear rather more than a lockstep summation of parts. And it's perhaps this phantom dimension that most intrigues the listener. Again perhaps, as in a difficult love affair, a resonance arises from the antipodal aspects of seeming incompatibility and obviously compelling attraction. One is therefore given to approach music so conceived as forever newly plowed ground. Odd, then, in terms of expectation, that the first electro-acoustic compositions incorporating magnetic tape appeared (as I write) just over forty years ago: New Grove cites Bruno Maderna's aptly titled Musica su due dimensione I, for flute and tape, and Edgard Varese's Deserts of 1950-54, for orchestra and tape, as among the earliest examples. Earlier still, in 1939, before the advent of magnetic tape, John Cage composed his Imaginary Landscape No. 1, for piano, Chinese cymbal, and two variable-speed turntables. Significant music marks the way as milestones, with regard particularly to this CD. Karlheinz Stockhausen's 1959-60 version of Kontakte, for tape, piano, and percussion; Milton Babbitt's 1963-64 Philomel, for soprano, recorded soprano, and synthesized tape; Babbitt's 1974 Reflections, for piano and synthesized tape; Roger Reynolds's Transfigured Wind IV from 1985, for flute, computer, and tape; and Mario Davidovsky's ten Synchronisms, for a variety of solo instruments, ensemble combinations, and tape. Eric Chasalow's choice to study with Davidovsky is significant. -

Informationen Als

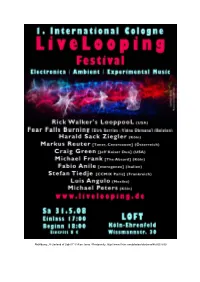

Abbildung: „A Garland of Light II“ © Alan Jaras / Reciprocity, http://www.flickr.com/photos/alanjaras/465037590 Pressemitteilung 1. Internationales Kölner LiveLooping - Festival 31. Mai 2008 im LOFT (Köln), Eintritt 8 Euro, Einlaß 17 Uhr, Beginn 18 Uhr Kontakt und Information: Michael Peters, [email protected], Tel. 02207-912144 Was ist denn „Livelooping“? Livelooping-Musiker sind meist Solo-Musiker, die digitale Loop-Geräte (im Prinzip Echogeräte mit u.U. sehr langer Laufzeit) benutzen, um sich selbst in Echtzeit zu „multiplizieren“, d.h. die live erzeugten Klänge zu wiederholen und zu komplexen Klangschichten aufzutürmen. Das können rhythmische Gebilde sein, aber auch dichte Wolken von Ambient-Klängen. Auch ganze Songstrukturen können live mit Loops aufgebaut und dann als Grundlage für Soli benutzt werden. Der erste Livelooper (damals noch mit Hilfe von Tonbandgeräten = Tape Loops) war der amerikanische Minimalist Terry Riley, der in den späten 60ern mit seinem psychedelischen Loop- Stück „A Rainbow in Curved Air“ und nächtelangen loop-basierten „All Night Flights“ weltbekannt wurde. Später brachte der Ambient-Musik-Erfinder Brian Eno, dessen erstes Ambient-Werk "Discreet Music" mit Tape Loops realisiert wurde, dem King-Crimson-Gitarristen Robert Fripp diese Technik bei. Fripp erzeugte dann in den späten 70ern mit seiner elektrischen Gitarre und seinem „Frippertronics“- Tonbandsystem ungewöhnliche Klanggebilde und machte die Möglichkeiten des Livelooping vor allem Gitarristen bewußt, die nach neuen musikalischen Wegen suchten. Seit den 80ern kann Livelooping mit Hilfe von analogen, später digitalen Loop-Delays erzeugt werden; es gibt mittlerweile eine reichhaltige Auswahl an einfachen und komplexen Loop-Geräten sowie an Software für das Livelooping aus dem Computer. Eine wachsende weltweite Community von Loop-Musikern diskutiert seit über 10 Jahren die technischen und musikalischen Aspekte des Livelooping auf der Loopers Delight-Internet-Mailingliste, und in Amerika, Europa und Japan finden regelmäßig Festivals für Loop-basierte Musik statt. -

Roedelius Bio Engl

ROEDELIUS: JARDIN AU FOU CD and Vinyl Release date: March 27th 2009 Cat No BB23 CD 927892/LP 927891 The essentials: ► Hans-Joachim Roedelius: born 1934; first record release in 1969 with Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Konrad Schnitzler), and active ever since as a solo artist and in various collaborations (amongst others with Moebius/Cluster, Moebius and Michael Rother/Harmonia, as well as with Brian Eno). One of the most prolific musicians of the German avant-garde and a key figure in the birth of Krautrock, synthesizer pop and ambient music. ► Jardin au Fou was first released on the French EGG label in 1979 ► produced by Peter Baumann (Tangerine Dream) ► liner notes by Asmus Tietchens ► CD features six bonus tracks: three remixes, three new tracks One of the most remarkable albums of the so-called Krautrock scene has to be Jardin au Fou by Hans-Joachim Roedelius (Cluster, Harmonia), issued in 1979. All the more noteworthy as it bore no resemblance whatsoever to what was expected of avant-garde electronica and displayed none of the typical Krautrock characteristics. Rhythm machine, sequencer and abstract sounds are conspicuous by their absence. Indeed, listeners were stunned by one of the most beautiful, charming, ethereal and peaceful albums in the history of German rock music. It was produced by Peter Baumann at his own Paragon Studios in 1978, a year after he left Tangerine Dream to concentrate on a solo career and production work. At the time, he was charged by the French label EGG with delivering three productions from the German electro/avant- garde/Krautrock cosmos. -

1973-Iceland.Pdf

-----=ca=rn=-.....z:-c, wrn=-:- --. n ===N::ll:-cI - .. • ~ en Place I Monday, June 18 I Tuesday, June 19 I Wednesday, Ju'!e 20 I I Thursday, June 21 I Friday, June 22 I Saturday, June 23 1 Sunday, June 24 10.00--12.00 10.00-12.00 10.00-12.00 Hotel General Assembly General Assembly General Assembly Loftleidir (if necessary) 14.00- 16.00 14.00-16.00 General Assembly General Assembly 12.00 Lvric Arts Trio Charpentier: --- The Symphony --- Nordic 17.00 17.00 22.00 House Norwegian Wood- Harpans Kraft Nonvegian jazz Wind Quintet from Sweden Bibalo, Berge, Salmenhaara, W elin, Mortensen, Nordheim - - -·- [_____ - 20.30 20.00 17.00 14.00 14.00 14.00 Miklatun Reception Tenidis, Kopelent TapeMusic Tape Music Tape Music Tape Music T6masson, Hall- Gilboa, Schurink grlmsson, Leifs Lambrecht, 20.00 20.00 17.00 Benhamou, Kim, Lyric Arts Trio German Trio Gaudeamus Tokunaga, Ishii, Doh!, Quartet Thommesen Zender, de Leeuw I Zimmermann, Raxach I Karkoschka, I Lutoslawski Haubenstock- Ramati, Hoffmann I I ---- --- -- - ' Exhibition of scores sent in by sections daily, at Miklatun --- - ISCM --- --- -- Hask6\abi6 21.00 Iceland Symphony Orchestra ThorarinssQn, Mallnes, Stevens, Endres, Gentilucci, Lachenmann, Krauze - - - - - -- -- -- ~ -- - State 17.00 Radio Icelandic Music on Tape - - - --- - --- -- Arnes Recital: Aitken/ Haraldsson I The President of the ISCM The President of the Icelandic Section In whatever way the 1973 Music Day may enter the history of It is a great pleasure for the Icelandic Section of the ISCM the ISCM, surely it will be remembered as the most Northern to receive the delegates of the sister organisations to the General point ever reached by the Society.