Orienting the Coppolas: a New Approach to U.S. Film Imperialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filmempfehlungsliste Der Medienwissenschaft Universität Bonn

Filmempfehlungsliste Medienwissenschaft Bonn 1. Spielfilme Klassiker der Filmgeschichte Titel Signatur (MeWi-Videothek) LE VOYAGE DANS LA LUNE (Die Reise zum Mond, R. : D 710.3 George Meliès, F 1902) DIE AUSTERNPRINZESSIN (R.: Ernst Lubitsch, D 1919) D 429.2 DAS CABINET DES DOKTOR CALIGARI (R. : Robert Wiene, D D 637.1, D 3.1, 1920) D 1144.1 C 15.1 NOSFERATU - EINE SYNFONIE DES GRAUENS (R.: Friedrich D 34.1 Wilhelm Murnau, D 1922) PANZERKREUZER POTEMKIN (R.: Sergej Eisenstein, UdSSR D 193.1, D 193.1, D 2312.1 1925) STREIK (R.: Sergej Eisenstein, UdSSR 1925) D 870.1 METROPOLIS (R.: Fritz Lang, D 1927) D 435.1, D 511.1 DER BLAUE ENGEL (R.: Josef von Sternberg, D 1930) D 6.1, D 6.2 LITTLE CAESAR (Der kleine Caesar, R.: Mervyn LeRoy, - USA 1931) M – EINE STADT SUCHT EINEN MÖRDER (R.: Fritz Lang, D D 435.2 1931) FRANKENSTEIN (R.: James Whale, USA 1931) D 392.1 IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (Es geschah in einer Nacht, R.: D 1016.1 Frank Capra, USA 1934) THE AWFUL TRUTH (Die schreckliche Wahrheit, R.: Leo D 2231.1 McCarey, USA 1937) LE QUAI DES BRUMES (Hafen im Nebel, R.: Marcel Carné, F D 817.1 1938) LA BETE HUMAINE (Bestie Mensch, R.: Jean Renoir, F 1938) D 67 BRINGING UP BABY (Leoparden küsst man nicht, R.: Howard D 2215.1 Hawks, USA 1938) THE WIZARD OF OZ (R.: Victor Fleming, USA 1939) D 599.1 NINOTCHKA (R.: Ernst Lubitsch, USA 1939) E 34.1 GONE WITH THE WIND (Vom Winde verweht, R.: Victor - Fleming, USA 1939) THE GREAT DICTATOR (Der große Diktator, R.: Charlie D 182.1 Chaplin, USA 1940) THE MALTESE FALCON (Die Spur des Falken, R.: John D 8.1 Filmempfehlungsliste Medienwissenschaft Bonn Huston, USA 1941) CITIZEN KANE (R.: Orson Welles, USA 1941) D 547.1 CASABLANCA (R.: Michael Curtiz, USA 1942) D 18., D 1576.1 TO BE OR NOT TO BE (Sein oder Nichtsein, R.: Ernst Lubitsch, USA 1942) DOUBLE INDEMNITY (Frau ohne Gewissen, R. -

8 Zł Kino Pod Baranami

bilety po 8 zł 1 3. WAKACYJNY FESTIWAL FILMOWY 28 czerwca - 29 sierpnia 2019 Kino Pod Baranami www.kinopodbaranami.pl bilety po 8 zł TYDZIEŃ 1: 28 czerwca - 4 lipca | 1st WEEK: June 28 - July 4 FILMY, KTÓRE CIĘ ODPRĘŻĄ | THE FILMS WHICH WILL CHILL YOU OUT 28.06 29.06 30.06 1.07 2.07 3.07 4.07 ARTYSTA | THE ARTIST (Michel Hazanavicius) FR 2011, 110' EN 17.00 19.00 15.00 CÓRKA TRENERA | A COACH'S DAUGHTER (Łukasz Grzegorzek) PL 2018, 96' PL 17.15 15.00 22.05 DESZCZOWA PIOSENKA | SINGIN' IN THE RAIN (Stanley Donen, Gene Kelly) US 1952, 103' EN 20.00 14.00 18.00 GENTLEMAN Z REWOLWEREM | THE OLD MAN & THE GUN (David Lowery) US 2018, 93' EN 15.00 19.15 16.00 JESTEM TAKA PIĘKNA! | I FEEL PRETTY (Abby Kohn, Marc Silverstein) US 2018, 110' EN 19.00 17.00 15.00 KSIĘGARNIA Z MARZENIAMI | THE BOOKSHOP (Isabel Coixet) GB/ES/DE 2018, 113' EN 19.00 15.00 17.00 LATO | LETO (Kirył Serebrennikow) RU/FR 2018, 129' RU/EN 15.00 22.15 19.00 MOJE WIELKIE WŁOSKIE GEJOWSKIE WESELE | PUOI BACIARE LO SPOSO (A. Genovesi) IT 2017, 98’ IT 16.00 14.00 22.00 NIEDOBRANI | LONG SHOT (Jonathan Levine) US 2019, 125' EN 22.00 17.45 16.00 OCEAN'S 8 | OCEAN'S 8 (Gary Ross) US 2019, 110' EN 16.00 22.15 20.00 PARYŻ MOŻE POCZEKAĆ | PARIS CAN WAIT (Eleanor Coppola) US 2016, 92' EN 15.00 16.00 19.15 POZYCJA OBOWIĄZKOWA | BOOK CLUB (Bill Holderman) US 2018, 113' EN 17.45 14.00 20.00 RAMEN. -

Customizable • Ease of Access • Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS • COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY A division of www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically for organizations such as Public Libraries, Recreation Centres, Schools and many more A Licence with Criterion-on-Demand includes 24/7 Access If you already have an annual Public Performance Licence from Criterion Pictures, you can add Criterion-on-Demand. Inquire Today 1-800-565-1996 or [email protected] A division of LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Children’s Films • Fox National Geographic • Animated Favourites • Warner Brothers • Classics • Paramount Pictures • Blockbuster Films • eOne • Documentaries • Elevation Pictures • Biographies • Mongrel Media • Literary Adaptations • MK2-Mile End • Academy Award Winners, and many more... etc. KEY FEATURES • Over 3,300 Feature Films and Documentaries, many available in French • Unlimited 24/7 Access with No Hidden Fees • Complete with Public Performance Rights for Communal Screenings • Huge Selection of Animated and Family Films • Access via IP Authentication • Features both “Current” and Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy to Use” Search Engine CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15,000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • *Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the -

The National Film Preserve Ltd. Presents the This Festival Is Dedicated To

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE THIS FESTIVAL IS DEDICATED TO Stanley Kauffmann 1916–2013 Peter O’Toole 1932–2013 THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE Julie Huntsinger | Directors Tom Luddy Kim Morgan | Guest Directors Guy Maddin Gary Meyer | Senior Curator Mara Fortes | Curator Kirsten Laursen | Chief of Staff Brandt Garber | Production Manager Karen Schwartzman | SVP, Partnerships Erika Moss Gordon | VP, Filmanthropy & Education Melissa DeMicco | Development Manager Joanna Lyons | Events Manager Bärbel Hacke | Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell | VP, Publicity Justin Bradshaw | Media Manager Jannette Angelle Bivona | Executive Assistant Marc McDonald | Theater Operations Manager Lucy Lerner | SHOWCorps Manager Erica Gioga | Housing/Travel Manager Beth Calderello | Operations Manager Chapin Cutler | Technical Director Ross Krantz | Technical Wizard Barbara Grassia | Projection and Inspection Annette Insdorf | Moderator Mark Danner | Resident Curators Pierre Rissient Peter Sellars Paolo Cherchi Usai Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Chief Writer Larry Gross (LG) Prized Program Contributors Sheerly Avni (SA), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Jesse Dubus (JD), Geoff Dyer (GD), Gian Luca Farinelli (GLF), Mara Fortes (MF), Scott Foundas (SF), Guy Maddin (GM), Leonard Maltin (LM), Jonathan Marlow (JM), Todd McCarthy (TM), Gary Meyer (GaM), Kim Morgan (KM), Errol Morris (EM), David Thomson (DT), Peter von Bagh (PvB) Tribute Curator Short Films Curators Student Prints Curator Chris Robinson Jonathan Marlow Gregory Nava and Bill Pence 1 Guest Directors Sponsored by Audible.com The National Film Preserve, Ltd. Each year, Telluride’s Guest Director serves as a key collaborator in the A Colorado 501(c)(3) nonprofit, tax-exempt educational corporation Festival’s programming decisions, bringing new ideas and overlooked films. -

16Th ANNUAL TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES EPIC

16th ANNUAL TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES EPIC BACK-TO-BACK SCREENINGS OF THE GODFATHER AND THE GODFATHER PART II TO CLOSE FESTIVAL, ALONG WITH EXCITING GALAS AND SPECIAL SCREENINGS Announced Galas Include: Sean “DIddy” Combs’ Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop: The Bad Boy Story, The Circle starrIng Tom Hanks and Emma Watson, and the TrIbeca/ESPN Sports Gala Mike and the Mad Dog along wIth SpecIal AnnIversary ScreenIngs of Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine, QuentIn TarantIno’s Reservoir Dogs, and Disney’s Aladdin New York, NY [March 8, 2017] – Unprecedented screenings and once-in-a-lifetime experiences, including the reunion of talent and creators from iconic films and musical acts, will be showcased at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival, presented by AT&T. The 16th edition of the annual cultural festival today announced the program’s Closing Night, Galas, Special Screenings, as well as the titles premiering under the Tribeca/ESPN Sports Film Festival banner. The Tribeca Film Festival takes place from April 19 to April 30 and opens with the world premiere of the feature documentary Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives at Radio City Music Hall, followed by a special concert featuring performances by Aretha Franklin, Jennifer Hudson, Earth, Wind & Fire, and more. To close the Festival, Tribeca will celebrate the 45th anniversary of The Godfather’s theatrical release with an epic screening of the legendary crime saga’s first two parts. The Godfather and The Godfather Part II will play back-to-back at Radio City Music Hall on Saturday, April 29, followed by a once-in-a- lifetime panel discussion with Academy Award®-winning director FrancIs Ford Coppola and actors Al PacIno, James Caan, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, TalIa ShIre, and Robert De NIro. -

Cinema-Booklet-Web.Pdf

1 AN ORIGINAL EXHIBITION BY THE MUSEO ITALO AMERICANO MADE POSSIBLE BY A GRANT FROM THE WRITTEN BY Joseph McBride CO-CURATED BY Joseph McBride & Mary Serventi Steiner ASSISTANT CURATORS Bianca Friundi & Mark Schiavenza GRAPHIC DESIGN Julie Giles SPECIAL THANKS TO American Zoetrope Courtney Garcia Anahid Nazarian Fox Carney Michael Gortz Guy Perego Anne Coco Matt Itelson San Francisco State University Katherine Colridge-Rodriguez Tamara Khalaf Faye Thompson Roy Conli The Margaret Herrick Library Silvia Turchin Roman Coppola of the Academy of Motion Walt Disney Animation Joe Dante Picture Arts and Sciences Research Library Lily Dierkes Irene Mecchi Mary Walsh Susan Filippo James Mockoski SEPTEMBER 18, 2015 MARCH 17, 2016 THROUGH THROUGH MARCH 6, 2016 SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 Fort Mason Center 442 Flint Street Rudolph Valentino and Hungarian 2 Marina Blvd., Bldg. C Reno, NV 89501 actress Vilma Banky in The Son San Francisco, CA 94123 775.333.0313 of the Sheik (1926). Courtesy of United Artists/Photofest. 415.673.2200 www.arteitaliausa.com OPPOSITE: Exhibit author and www.sfmuseo.org Thursdays through co-curator Joseph McBride (left) Tuesdays through Sundays 12 – 4 pm Sundays 12 – 5 pm with Frank Capra, 1985. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures. 2 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Italian American Cinema: From Capra to the Coppolas 6 FOUNDATIONS: THE PIONEERS The Long Early Journey 9 A Landmark Film: The Italian 10 “Capraesque” 11 The Latin Lover of the Roaring Twenties 12 Capra’s Contemporaries 13 Banking on the Movies 13 Little Rico & Big Tony 14 From Ellis Island to the Suburbs 15 FROM THE STUDIOS TO THE STREETS: 1940s–1960s Crooning, Acting, and Rat-Packing 17 The Musical Man 18 Funnymen 19 One of a Kind 20 Whaddya Wanna Do Tonight, Marty? 21 Imported from Italy 22 The Western All’italiana 23 A Woman of Many Parts 24 Into the Mainstream 25 ANIMATED PEOPLE The Golden Age – The Modern Era 26 THE MODERN ERA: 1970 TO TODAY Everybody Is Italian 29 Wiseguys, Palookas, & Buffoons 30 A Valentino for the Seventies 32 Director Frank Capra (seated), 1927. -

Paris Can Wait

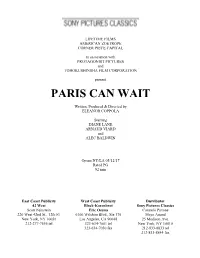

LIFETIME FILMS AMERICAN ZOETROPE CORNER PIECE CAPITAL In association with PROTAGONIST PICTURES and TOHOKUSHINSHA FILM CORPORATION present PARIS CAN WAIT Written, Produced & Directed by ELEANOR COPPOLA Starring DIANE LANE ARNAUD VIARD and ALEC BALDWIN Opens NY/LA 05/12/17 Rated PG 92 min East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor 42 West Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Scott Feinstein Eric Osuna Carmelo Pirrone 220 West 42nd St., 12th Fl. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Ste 170 Maya Anand New York, NY 10036 Los Angeles, CA 90048 25 Madison Ave. 212-277-7555 tel 323-634-7001 tel New York, NY 10010 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8833 tel 212-833-8844 fax CAST Anne Lockwood Diane LANE Jacques Clement Arnaud VIARD Michael Lockwood Alec BALDWIN Martine Elise TIELROOY Carole Elodie NAVARRE Mechanic Serge ONTENIENTE Philippe Pierre CUQ Musée Des Tissus Guard Cédric MONNET Concierge Aurore CLEMENT Suzanne Davia NELSON Alexandra Eleanor LAMBERT FILMMAKERS Written, Produced and Directed by ELEANOR COPPOLA Produced by FRED ROOS Executive Producers MICHAEL ZAKIN LISA HAMILTON DALY TANYA LOPEZ ROB SHARENOW MOLLY THOMPSON Director of Photography CRYSTEL FOURNIER, AFC Production Designer ANNE SEIBEL, ADC Costume Designer MILENA CANONERO Editor Glen Scantlebury Sound Designer RICHARD BEGGS Music by LAURA KARPMAN Synopses LOG LINE A devoted American wife (Diane Lane) with a workaholic inattentive husband (Alec Baldwin) takes an unexpected journey from Cannes to Paris with a charming Frenchman (Arnaud Viard) that reawakens her sense of self and joie de vivre. LONG SYNOPSIS Eleanor Coppola’s narrative directorial and screenwriting debut stars Academy Award® nominee Diane Lane as a Hollywood producer’s wife who unexpectedly takes a trip through France, which reawakens her sense of self and her joie de vivre. -

The Joys of Teaching Literature

THE JOYS OF TEACHING LITERATURE VOLUME 10: September 2019-August 2020 Sara Martín Alegre Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2020 Contents 2 September 2019 / ‘READ, READ, READ AND THEN WHAT?’: GOOD QUESTION… ........ 1 9 September 2019 / THE DANCE OF TIME: ONE STEP FORWARD, THREE SIDEWAYS, ALWAYS RUNNING BEHIND .............................................................................................. 3 17 September 2019 / WHEN DID THE FUTURE DIE? SCATTERED THOUGHTS ON PALEOFUTURISM AND UTOPIA ........................................................................................ 6 24 September 2019 / TIME AND J.B. PRIESTLEY: I HAVE BEEN HERE BEFORE ................. 9 1 October 2019 / LIKE WRITING A MUSICAL SCORE: THE UNACKNOWLEDGED TASK OF THE SCREENWRITER ....................................................................................................... 12 8 October 2019 / A VISIT TO THE LIBRARY: THE SAD LOOK OF YELLOWING BOOKS ..... 16 22 October 2019 / LUNCH WITH A WRITER: NECESSARY ENCOUNTERS ....................... 19 29 October 2019 / WHAT AN UGLY IMAGINATION IS ABOUT (TRYING TO MAKE SENSE OF MY OWN IDEAS) ........................................................................................................ 21 4 November 2019 / IN SEARCH OF CHIVALRY: WALTER SCOTT’S IVANHOE .................. 24 12 November 2019 / THE COMPLEX MATTER OF CULTURAL APPROPRIATION (WITH THOUGHTS ON THE NATIVE AMERICAN CASE) .............................................................. 28 19 -

1 the Feeling of Falling: a Student Filmmaker's

1 The Feeling of Falling: A Student Filmmaker’s Approach to Short Narrative Filmmaking ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film ______________________________________ by Jordan Sommerlad April, 2013 2 “Making a film is like a stagecoach ride in the old west. When you start, you are hoping for a pleasant trip. By the halfway point, you just hope to survive.” -Francois Truffaut- When Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez finished directing The Blair Witch Project on a micro-budget of $60,000, they returned the camcorder they bought from Circuit City in order to stretch their money as far as possible. Kevin Smith shot his film Clerks at the convenience store he worked at for $27,000 by maxing out credit cards and begging family and friends for extra cash. Robert Rodriguez paid for his first $7000 feature, El Mariachi, by subjecting himself to experimental drug tests for extra cash. My film, The Feeling of Falling, was initially intended to be a tribute to the struggles, anxieties, and downright insanity of these filmmakers who had nothing to lose and everything to gain. For nearly five months, I wrote a script about a horror film gone wrong. My story was stuck in what is called “development hell,” a period in which scripts struggle to emerge from the haze and get the stamp of approval from the powers that be. But my screenplay was never fully finished, and the words on the page were for all practical purposes, impossible to film. -

True Films 3.0

TRUE FILMS 3.0 This is the golden age of documentaries. Inexpensive equipment, new methods of distribution, and a very eager audi- ence have all launched a renaissance in non-fiction film making and viewing. The very best of these non-fiction films are as entertaining as the best Hol- lywood blockbusters. Because they are true, their storylines seem fresh with authentic plot twists, real characters, and truth stranger than fiction. Most true films are solidly informative, and a few are genuinely useful like a tool. The rise of documentaries and true cinema is felt not only in movie theaters, but on network TV and cable channels as well. Reality TV, non-fiction stations like the History Channel or Discovery, and BBC imports have increased the choices in true films tremendously. There’s no time to watch them all, and little guidance to what’s great. In this book I offer 200+ great true films. I define true films as documentaries, educational films, instructional how-to’s, and what the British call factuals – a non-fiction visual account. These 200 are the best non-fiction films I’ve found for general interest. I’ve watched all these films more than once. Sometimes thrice. I haven’t had TV for 20 years, so I’ve concentrated my viewing time on documentaries and true films. I run a little website (www.truefilms.com) where I solicit suggestions of great stuff. What am I looking for in a great true film? • It must be factual. • It must surprise me, but not preach to me. -

Rome Film Fest October 18 | 27 2007 LA STORIA DEL CINEMA

Rome Film Fest October 18 | 27 2007 LA STORIA DEL CINEMA IN CINEMA MON AMOURAMOUR L’INTERMINABILE PASSIONE TRA BNL E IL GRANDE CINEMA cinema.bnl.it BNL MAIN PARTNER di “Cinema. Festa Internazionale di Roma” Roma, 18 - 27 ottobre Founding Members Advisory Board General Manager Comune di Roma Tullio Kezich Francesca Via Camera di Commercio di Roma President Regione Lazio Artistic Direction Provincia di Roma Paolo Bertetto Maria Teresa Cavina Fondazione Musica per Roma Gianni Canova Cinema 2007 Teresa Cavina and New Cinema Network Foundation Committee Giuseppe Cereda Piera Detassis Andrea Mondello Stefano Della Casa Première President Piera Detassis Gianluca Giannelli Giorgio De Vincenti Alice in the City Board of Directors Carlo Freccero Giorgio Gosetti Goffredo Bettini Gianluca Giannelli Cinema 2007 e CINEMA President Giorgio Gosetti The Business Street Franco La Polla Gaia Morrione Counsellors Marie-Pierre Macia Eventi Speciali Andrea Mondello Antonio Monda Mario Sesti MON AMOUR Carlo Fuortes Renato Nicolini Extra Vanni Piccolo Auditors Mario Sesti Daniela Lambardi Giorgio Van Straten President Staff Auditors Gianfranco Piccini Giovanni Sapia Supply Auditors Demetrio Minuto Antonella Greco WWW.AAMS.IT I GIOCHI PUBBLICI FINANZIANO LO SPORT, L'ARTE E LA CULTURA. CON I GIOCHI DI AAMS SI DEVOLVONO FONDI PER LO SPORT, L'ARTE E LA CULTURA. QUEST'ANNO AAMS È PARTNER DI "CINEMA. FESTA INTERNAZIONALE DI ROMA” E ASSEGNA IL PREMIO PER IL MIGLIOR FILM E IL PREMIO DEL PUBBLICO “ALICE NELLA CITTÀ”. VIENI A SCOPRIRE AAMS ALL'AUDITORIUM PARCO DELLA MUSICA. "CINEMA. FESTA INTERNAZIONALE DI ROMA - SOSTIENE LA FAO E LA SUA LOTTA CONTRO LA FAME” / “ROME FILM FEST - SUPPORTS FAO AND ITS FIGHT AGAINST HUNGER”. -

Graves-Thesis

THE ESTRANGED WORLD: THE GROTESQUE IN SOFIA COPPOLA’S YOUNG GIRLS TRILOGY by Stephanie A. Graves A thesis submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Middle Tennessee State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Dr. David Lavery, Chair Dr. Robert Holtzclaw I dedicate this work to my amazing coterie of friends and academic companions, Lisa Williams, Nancy Roche, and Jessica Szalacinski, whose interest in this project and tireless support has meant the world to me. I’d also like to dedicate this thesis to my family: Sarah Chamlee, who has always made me feel that what I’ve been working on was interesting; Roy and Mary Beth Chamlee, who have gifted me with their love and welcomed me into their family; my mother, Ann Graves, who has been a steadfast cheerleader and source of love and inspiration as well as a model of strength; and to my beloved husband, Zeb Chamlee, for his endless support, for all the meals he cooked and dishes he washed while I was indisposed with this project, and for his unyielding love and friendship. Thanks, y’all. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to Dr. Marion Hollings, who first suggested that I was well suited to academic endeavors. Her guidance and instruction have been invaluable. Many thanks also to Dr. Allen Hibbard, who taught me how to engage with critical theory in a forthright and fearless manner. I am particularly grateful to Dr. Robert Holtzclaw for serving as my reader; his insights and encouragement certainly improved my work.