The Gillanderses”, Published in West Highland Notes & Queries, Ser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAFT Pitch and Facility Strategy

Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 2.METHODOLOGY 10 3. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY – PITCH SPORTS 16 4. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY – OTHER OUTDOOR SPORTS AND ACTIVITIES 33 5. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY - INDOOR FACILITIES 41 6.CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Appendices 1 STUDY CONSULTEES 2 STRATEGY CONTEXT 3 METHODOLOGY IN DETAIL 4 DEMAND AUDIT TABLE 5 SUPPLY AUDIT TABLE 6 PPM MODEL ANALYSIS 7 MAPS Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Maps Map 1 All Playing Pitch Sites Map 2 All Playing Pitch Sites by Pitch Type Map 3 All Playing Pitch Sites by Pitch Quality Map 4 All Swimming Pools Map 5 All Sports Halls Map 6 All Fitness Suites Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Executive Summary Strategic Leisure, part of the Scott Wilson Group, was commissioned by Orkney Islands Council (OIC) in December 2010 to develop a Sports Facilities and Pitch Strategy. This report details the findings of the research and assessment undertaken and the recommendations made on the basis of this evidence. The recommendations provide the strategy for the future provision of sports pitches, indoor and outdoor sports facilities, guide management and operation and provide a framework for funding and investment decisions. Aims, Objectives and Strategic Scope The aim of the study is to produce a robust, well-evidenced and achievable Sports Facility and Pitch Strategy for OIC, which takes account of the demand for, and provision of, indoor and outdoor sport and leisure facilities that are readily available for community activities, with an accompanying Playing Pitch Strategy. -

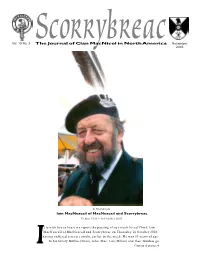

Scorrybreac Page A

Vol. 19 No. 3 The Journal of Clan MacNicol in North America November Scorrybreac 2003 In Memoriam Iain MacNeacail of MacNeacail and Scorrybreac 19 June 1921 – 15 October 2003 t is with heavy heart we report the passing of our much loved Chief, Iain MacNeacail of MacNeacail and Scorrybreac on Thursday 16 October 2003, having suffered a severe stroke earlier in the week. He was 83 years of age. To his family Bobbie (Allan), John, Mac, Lisa (Dillon) and their families go III Continued on page 4 Scorrybreac From The President his is an exceptional time in the life of our Clan. planning our first ever annual Our beloved Chief Scorrybreac has passed on, gathering in Texas to be held in leaving his family and all of us bereft. He was the late spring of 2004. Prepara- TTtruly the father of the modern Clan, having presided tions for the 2004 Skye Inter- over its revival and return to a glory not known for several national Gathering are proceed- centuries. We give thanks for the lives of Scorrybreac and ing apace under the management Pam, for their warmth, their humanity, and their dedica- of David Nicolson, Jan Nicolson tion to the Clan. Together, they represented us so well and other Scottish members. We Jeremy Nicholson around the world and evoked such admiration and respect expect a major turn-out in Portree from all those they met. People of all walks of life were for the weekend of October 14. John, our new Chief, will touched by their kindness, solicitude and good humor. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Hammond Burke Nicholson, Jr

US $10.00 VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2 DecemberScorrybreac 2007 The Journal of Clan MacNicol of North America Hammond Burke Nicholson, Jr. June 14, 1917 —June 27, 2007 BARON OF BALVENIE, CHIEFTAIN IN CLAN MACNICOL AND CHAIRMAN, THE HIGHLAND CLAN MACNEACAIL FEDERATION Obituary from the 1 August 2007 Issue of The Scotsman He helped pioneer the Coca-Cola business in Europe, in Edinburgh: and was Senior Vice President of the company in Atlanta, Georgia. He developed the brand in Europe, HAMMOND Burke Nicholson Jr., who has died in his and became a major player in the long standing 91st year, was a senior executive of the Coca-Cola Corporation corporate war with rival Pepsi-Cola. who became a significant benefactor in Scottish cultural life. (OBITUARY, CONTINUES ON PAGE 5) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2 Feature OBITUARY OF BURKE NICHOLSON OF BALVENIE ..........................................1 from the 1 August 2007 Issue of The Scotsman in Edinburgh TRIBUTES TO BURKE NICHOLSON OF BALVENIE ...........................................5 Murray Nicolson, John Nicoll Announcements WEDDING .......................................................................................................................8 Chief’s Son and Heir Weds Floridian Fiancée RENEWALS ....................................................................................................................15 Last Chance for 2007 Renewal and Membership Certificate NEW WEBSITE IN THE WEST ..................................................................................21 NEW CLAN BADGE -

Traditions of the Macaulays of Lewis. 367

.TRADITION THF SO E MACAULAY3 36 LEWISF SO . VII. TRADITION E MACAULAYTH F SO . LEWISF L SO . CAPTY W B . .F . THOMAS, R.N., F.S.A. SCOT. INTRODUCTION. Clae Th n Aulay phonetia , c spellin e Gaelith f go c Claim Amhlaeibli, takes its name from Amhlaebh, which is the Gaelic form of the Scandinavian 6ldfr; in Anglo-Saxon written Auluf, and in English Olave, Olay, Ola.1 There are thirty Olafar registered in the Icelandic Land-book, and, the name having been introduce e Northmeth e y Irishdb th o t n, there ear thirty-five noticed in the " Annals of the Four Masters."2 11te 12td th han hn I centuries, when surnames originatet no thef i , d ydi , were at least becoming more general, the original source of a name is, in the west of Scotland, no proof of race ; or rather, between the purely Norse colony in Shetland and the Orkneys, and the Gael in Scotland and Ireland, there had arisen a mixture of the two peoples who were appropriately called Gall-Gael, equivalen o sayint t g they were Norse-Celt r Celtio s c Northmen. Thus, Gille-Brighde (Gaelic) is succeeded by Somerled (Norse); of the five sons of the latter, two, Malcolm and Angus, have Gaelic names havo tw ;e Norse, Reginal fifte th Olafd h d an bear an ; sa Gaelic name, Dubhgall,3 which implies that the bearer is a Dane. Even in sone th Orknef Havar sf o o o Hakoe ydtw ar Thorsteind n an e thirth t d bu , is Dufniall, i.e., Donald.4 Of the Icelandic settlers, Becan (Gaelic) may 1 " Olafr," m. -

SB-4207-January-NA.Pdf

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 42 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 42 36 36 NumberNumber Number 711 11 TheThe The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international ScottishScottish Scottish newspaper newspaper May January May 2013 2013 2019 Up Helly Aa Lighting up Shetland’s dark winter with Viking fun » Pg 16 2019 - A Year in Piping » Pg 19 US Barcodes A Literary Inn ............................ » Pg 8 The Bards Discover Scotland’s Starry Nights ................................ » Pg 9 Scotland: What’s New for 2019 ............................. » Pg 12 Family 7 25286 844598 0 1 The Immortal Memory ........ » Pg 29 » Pg 25 7 25286 844598 0 9 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 42 - Number 7 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Marrickville South, Starting the year Sean Cairney NSW, 2204 Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF Jim Stoddart [email protected] Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot The National Piping Centre North American Office: off Scottish style PO Box 6880 David McVey Cathedral you were a Doonie, with From Scotland to the world, Burns Angus Whitson Hudson, FL 34674 Lady Fiona MacGregor [email protected] Uppies being those born to the south, Suppers will celebrate this great Eric Bryan or you play on the side that your literary figure from Africa to America. -

The Nicolsons”, Published in West Highland Notes & Queries, Ser

“1467 MS: The Nicolsons”, published in West Highland Notes & Queries, ser. 4, no. 7 (July. 2018), pp. 3–18 1467 MS: The Nicolsons The Nicolsons have been described as ‘the leading family in the Outer Hebrides towards the end of the Norse period’, but any consideration of their history must also take account of the MacLeods.1 The MacLeods do not appear on record until 1343, when David II granted two thirds of Glenelg to Malcolm son of Tormod MacLeod of Dunvegan, and some lands in Assynt to Torquil MacLeod of Lewis;2 nor do they appear in the 1467 MS, which the late John Bannerman described as ‘genealogies of the important clan chiefs who recognised the authority of the Lords of the Isles c. 1400’.3 According to Bannerman’s yardstick, either the MacLeods had failed to recognise the authority of the lords of the Isles by 1400, or they were simply not yet important enough to be included. History shows that they took the place of the Nicolsons, who are not only included in the manuscript, but given generous space in the fourth column (NLS Adv. ms 72.1.1, f. 1rd27–33) between the Mathesons and Gillanderses, both of whom are given much less. It seems that the process of change was far from over by 1400. The circumstances were these. From c. 900 to 1266 Skye and Lewis belonged to the Norse kingdom of Man and the Isles. During the last century of this 366- year period, from c. 1156, the Norse-Gaelic warrior Somerled and his descendants held the central part of the kingdom, including Bute, Kintyre, Islay, Mull and all the islands as far north as Uist, Barra, Rum, Eigg, Muck and Canna. -

History of the Macleods with Genealogies of the Principal

*? 1 /mIB4» » ' Q oc i. &;::$ 23 j • or v HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS. INVERNESS: PRINTED AT THE "SCOTTISH HIGHLANDER" OFFICE. HISTORY TP MACLEODS WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. Scot., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY AND GENEALOGIES OF THE CLAN MACKENZIE"; "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERON'S;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS ; " "THE " PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER ; " THE HISTORICAL TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLANDS;" "THE HISTORY " OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" " THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE IN 1882-83;" ETC., ETC. MURUS AHENEUS. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXXIX. J iBRARY J TO LACHLAN MACDONALD, ESQUIRE OF SKAEBOST, THE BEST LANDLORD IN THE HIGHLANDS. THIS HISTORY OF HIS MOTHER'S CLAN (Ann Macleod of Gesto) IS INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/historyofmacleodOOmack PREFACE. -:o:- This volume completes my fifth Clan History, written and published during the last ten years, making altogether some two thousand two hundred and fifty pages of a class of literary work which, in every line, requires the most scrupulous and careful verification. This is in addition to about the same number, dealing with the traditions^ superstitions, general history, and social condition of the Highlands, and mostly prepared after business hours in the course of an active private and public life, including my editorial labours in connection with the Celtic Maga- zine and the Scottish Highlander. This is far more than has ever been written by any author born north of the Grampians and whatever may be said ; about the quality of these productions, two agreeable facts may be stated regarding them. -

CLAN MAP Final

Shetland Orkney Western Isles Rousay Shapinsay Scotland Orkney Islands Stronsay Northern. Ireland Republic of Hoy Ireland England Wales £ Castle of Mey £ Sinclair and Girnigoe Morrison Sinclair s Mackay e l Lewis Oliphant s Gunn I MacLeod S U T H E R L MACLEOD A N D MacKenzie n Dunrobin£ r e Harris MacDonnell t R O s S MacLeod S Spynie e £ North Munro Brodie W Uist Z I Brodie £ Innes Cumming MacDonald E N Leod £ C K Cawdor £ Rose Keith A Huntly £ Urquhart B Culloden 1746 £ Benbecula £Dunvegan M £ Fyvie MacLeod Fraser INVERNESS Balvenie MacDonald N Chisolm MacKintosh O Leslie £Urquhart D Kildrummy South MacKinnon £ Grant £ Eilean Donan R Skene Uist Grant O £ Skye MacRae Craigievar£ Fraser G Forbes ABERDEEN FraserClan Chattan Menzies £ MacLeod Crathes £ Drum Braemar MacDonald MacDonnell £Balmoral Barra MacNeil £ Burnett MacDonald of Rum of Keppoch Keith Clan Ranald Farquharson £ Dunnottar C A Stewart MacDonnell of GlenM Garry Macpherson Lindsay Edzell Eigg £ E R £ Inverlochy O £ Barclay Tioram £ N Blair B Killicrankie 1689 Graham MacIain MacLean MacDonald Robertson Murray Coll MacInnes Stewart Ogilvie £ Glamis MacLean Stalker£ MacKinnon P B E L L Menzies Carnegie A M £ C Ruthven Claypotts Tiree Staffa £ £ DUNDEE Mull Duart Dunstaffnage Murray PERTH Hay £ MacNab £ MacLean Kilchurn Huntingtower Iona MacGregor £ £ MacDougall Drummond Rollo MacDuff St. Andrews Inveraray£ MacFarlane Drummond Lindsay £Kellie Sherriffmuir 1715B £Campbell £ £ BuchananGraham Doune Leven £ Falkland Stirling£ MacFie Campbell STIRLING Colonsay MacLachlan ErskineBruce -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. -

Inverness Gaelic Society

Inverness Gaelic Society Collection Last Updated Jan 2020 Title Author Call Number Burt's letters from the north of Scotland : with facsimiles of the original engravings (Burt, Edward), d. 1755 941.2 An English Irish dictionary, intended for the use of schools : containing upwards of eight thousand(Connellan, English Thaddeus),words, with d. their 1854 corresponding explanation491.623 in Irish The martial achievements of the Scots nation : being an account of the lives, characters and memorableAbercromby, actions, Patrick of such Scotsmen as have signaliz'd941.1 themselves by the sword at home and abroad and a survey of the military transactions wherein Scotland or Scotsmen have been remarkably concern'd from thefirst establishment of the Scots monarchy to this present time Officers and graduates of University & King's College, Aberdeen MVD-MDCCCLX Aberdeen. University and King's College 378.41235 The Welsh language 1961-1981 : an interpretative atlas Aitchison, J. W. 491.66 Scottish fiddlers and their music Alburger, Mary Anne 787.109411 Place-names of Aberdeenshire Alexander, William M. 929.4 Burn on the hill : the story of the first 'Compleat Munroist' Allan, Elizabeth B.BUR The Bridal Caölchairn; and other poems Allan, John Carter, afetrwards Allan (John Hay) calling808.81 himself John Sobiestki Stolberg Stuart Earail dhurachdach do pheacaich neo-iompaichte Alleine, Joseph 234.5 Earail Dhurachdach do pheacaich neo-iompaichte Alleine, Joseph 234.5 Leabhar-pocaid an naoimh : no guth Dhe anns na Geallaibh Alleine, Joseph 248.4 My little town of Cromarty : the history of a northern Scottish town Alston, David, 1952- 941.156 An Chomhdhail Cheilteach Inbhir Nis 1993 : The Celtic Congress Inverness 1993 An Chomhdhail Cheilteach (1993 : Scotland) 891.63 Orain-aon-neach : Leabhar XXI. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver ....