Board Paper AAB/17/2019-20 (Annex B)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Yu (University of British Columbia) and Elizabeth Sinn

Crossing Seas Editors: Henry Yu (University of British Columbia) and Elizabeth Sinn (University of Hong Kong) The Crossing Seas series brings together books that investigate Chinese migration from the migrants’ perspective. As migrants traveled from one destination to another throughout their lifetime, they created and maintained layers of different networks. Along the way these migrants also dispersed, recreated, and adapted their cultural practices. To study these different networks, the series publishes books in disciplines such as history, women’s studies, geography, cultural anthropology, and archaeology, and prominently features publications informed by interdisci- plinary approaches that focus on multiple aspects of the migration processes. Books in the series: Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949 Edited by John Fitzgerald and Hon-ming Yip Returning Home with Glory: Chinese Villagers around the Pacific, 1849 to 1949 Michael Williams Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949 Edited by John Fitzgerald and Hon-ming Yip Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong https://hkupress.hku.hk © 2020 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8528-26-4 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover image: Local Chinese participate in fund-raising festival in colonial Australia. “Beechworth Carnival: The Procession of Chinese.” Engraver unknown. -

(Cap. 53) Antiquities and Monuments (Declaration of Monuments and Historical Buildings) (Consolidation) (Amendment) Notice 2020

File Ref.: DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/141 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) Antiquities and Monuments (Declaration of Monuments and Historical Buildings) (Consolidation) (Amendment) Notice 2020 INTRODUCTION After consultation with the Antiquities Advisory Board (“AAB”)1 and with the approval of the Chief Executive, the Secretary for Development (“SDEV”), in his capacity as the Antiquities Authority under the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) (the “Ordinance”), has decided to declare three historic items, i.e. the masonry bridge of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir (薄扶林水塘石橋), Tung Wah Coffin Home (東華義莊) and Tin Hau Temple and the adjoining buildings (天后古廟及其鄰接建築物), as monuments2 under section 3(1) of the Ordinance. 2. The declaration is made by the Antiquities and Monuments (Declaration of Monuments and Historical Buildings) (Consolidation) A (Amendment) Notice 2020 (the “Notice”) (Annex A), which will be published in the Gazette on 22 May 2020. 1 The Antiquities Advisory Board is a statutory body established under section 17 of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) to advise the Antiquities Authority on any matters relating to antiquities, proposed monuments or monuments or referred to it for consultation under sections 2A(1), 3(1) or 6(4) of the Ordinance. 2 Under section 2 of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53), “monument” (古蹟) means a place, building, site or structure which is declared to be a monument, historical building or archaeological or palaeontological site or structure. JUSTIFICATIONS Heritage Significance 3. The Antiquities and Monuments Office (“AMO”)3 has carried out research on and assessed the heritage significance of the three historic items set out in paragraph 1 above. -

Glossary of Place Names for the Chinese Australian Hometown Heritage Tour, March 2017

Glossary of place names for the Chinese Australian Hometown Heritage Tour, March 2017 Chinese English name or characters Mandarin (pinyin) Cantonese (Yale) ‘Chinese postal romanisation’ (traditional) HONG KONG Hong Kong 香港 Xiānggǎng Hēunggóng Tsim Sha Tsui (TST) 尖沙嘴 Jiānshāzuǐ Jīmsājéui Pokfulam 薄扶林 Bófúlín Bohkfùhlàhm Tung Wah Coffin Home 東華義莊 Dōnghuá yìzhuāng Dūngwah yihjōng Hong Kong China Ferry Terminal 中港碼頭 Zhōnggǎng mǎtóu Jūnggóng máhtàuh GUANGDONG Canton [province], Kwangtung 廣東 Guǎngdōng Gwóngdūng Canton [city], Kwangchow (Foo) 廣州(府) Guǎngzhōu(fǔ) Gwóngjāu(fú) Pearl River Delta 珠江三角洲 Zhūjiāng sānjiǎo zhōu Jyūgōng sāamgok jāu Sze Yap, See Yup, Four Counties 四邑 Sìyì Seiyāp Wuyi, Five Counties 五邑 Wǔyì Ńghyāp Sam Yap, Three Counties 三邑 Sānyì Sāamyāp JIANGMEN Kongmoon, Jiangmen 江門 Jiāngmén Gōngmùhn Jiangmen Port 江門港 Jiāngméngǎng Gōngmùhngóng Xi River, West River 西江 Xījiāng Sāigōng Jiāngmén Wǔyì Gōngmùhn Ńghyāp Wuyi Museum of Overseas Chinese, 江門五邑華僑 huàqiáo huàrén wahkìuh wahyàhn Jiangmen Museum 華人博物馆 bówùguǎn bokmahtgún Ńghyāp daaihhohk 五邑大學中國 Wǔyì dàxué Zhōngguó Wuyi University Overseas Chinese Jūnggwok kìuhhēung 僑鄉文化研究 qiáoxiāng wénhuà Culture Research Centre màhnfa yìhngau 中心 yánjiù zhōngxīn jūngsām Pengjiang 蓬江 Péngjiāng Fùhnggōng KAIPING Hoiping, Kaiping 開平 Kāipíng Hōipèhng Kaiping diaolou 開平碉樓 Kāipíng diāolóu Hōipèhng dīulàuh Tangkou 塘口 Tángkǒu Tòhngháu Cangdong 倉東 Cāngdōng Chōngdūng Cangdong Heritage Education Chōngdūng gāauyuhk 倉東教育基地 Cāngdōng jiàoyu jīdì Centre gēideih Li Yuan, Li Garden 立園 Lìyuán Laahpyùhn Glossary of place -

Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital

Heritage Impact Assessment for Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR TUNG WAH MUSEUM In Respect of THE REDEVELOPMENT OF KWONG WAH HOSPITAL PREPARED FOR HOSPITAL AUTHORITY I TUNG WAH GROUP OF HOSPITALS I KWONG WAH HOSPITAL ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT SIMON KWAN & ASSOCIATES LTD. HERITAGE CONSERVATION CONSULTANT URBANAGE INTERNATIONAL LTD. May 2015 Heritage Impact Assessment for Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 1.2 Site Location 1.3 Objectives and Scope of Heritage Impact Assessment 1.4 Methodology 1.5 Acknowledgements 1.6 Definitions 2.0 HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL APPRAISAL 2.1 Historical Development 2.2 Founding of Kwong Wah Hospital 2.3 Redevelopment of 1950s-1960s 2.4 Conversion to Tung Wah Museum 2.5 Chronological Events 2.6 Architectural Appraisal 2.6.1 Study Area 2.6.2 General Description of the Existing Buildings 2.6.3 Tung Wah Museum 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE VALUE 3.1 Cultural Significance 3.2 Statement of Cultural Significance 3.3 Character Defining Elements 3.3.1 External Elements 3.3.2 Internal Elements Heritage Impact Assessment for Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital 4.0 CONSERVATION POLICIES 4.1 Conservation Objectives 4.2 Conservation Principles 5.0 REDEVELOPMENT SCHEME 5.1 Design Options 5.2 Design Principles Adopted in Option 3C 5.3 Latest Proposed Scheme for the Redevelopment 6.0 ASSESSMENT OF IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES 6.1 Potential Impacts 6.2 Mitigation Measures 6.3 Enhancement -

List of the 1444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results

List of the 1,444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results (as at 9 Sept 2021) Page 1 Proposed Year of Construction / Remarks Number Name and Address 名稱及地址 Ownership Grading Restoration 備註 Grade 1 confirmed on 18 Dec 2009 Tsang Tai Uk, Sha Tin, N.T. 新界沙田曾大屋 1 Private Built 1847-1867 1 二○○九年十二月十八日確定為一級歷史建築 Combined with numbers 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with The Wai was built between Kat Hing Wai, Shrine, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍神廳 1 Private 1465 and 1487, the wall 2 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號3、4、5、6和7合併為一項, N.T. was 1662-1722. 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Entrance Gate, Kam Tin, 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 3 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍圍門 1 Private Yuen Long, N.T. was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、4、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northwest) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 4 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. (西北)及圍牆 was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、3、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northeast) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 5 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. -

活化@Heritage Issue No. 71

Issue No.71 June 2020 薄扶林水塘石橋、東華義莊和油麻地天后古廟及其鄰接 建築物列為法定古蹟 The Masonry Bridge of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir, the Tung Wah Coffin Home, and Tin Hau Temple and the Adjoining Buildings in Yau Ma Tei Declared as Monuments 府於2020年5月22日宣布將位於薄扶林水 he Government announced the declaration of the masonry bridge of Pok Fu Lam 政塘內的石橋、大口環道的東華義莊和油麻 TReservoir, the Tung Wah Coffin Home on Sandy Bay Road, and Tin Hau Temple and 地的天后古廟及其鄰接建築物列為法定古蹟。現 the adjoining buildings in Yau Ma Tei as monuments on 22 May 2020. This brings the 時香港法定古蹟數目增加至126項。 number of declared monuments in Hong Kong to 126. 薄扶林水塘是香港首個公共水塘,於1860年建 Pok Fu Lam Reservoir is the first public reservoir in Hong Kong; its construction 造,至1863年年底開始供水。現列為法定古蹟 commenced in 1860 and water supplies began at the end of 1863. The masonry bridge, 的石橋是薄扶林水塘現存最古老的歷史構築物之 the newly declared monument, is one of the oldest surviving historic structures of Pok 一。這座石橋與另外四條位於薄扶林水塘道並已 Fu Lam Reservoir. This bridge, together with the other four masonry bridges on Pok 於2009年列為法定古蹟的石橋,不但為水塘其 Fu Lam Reservoir Road that were declared monuments in 2009, provide not only an 他水務設施提供不可或缺的連接,亦為維修保養 indispensable linkage with the reservoir's other waterworks facilities, but also access 及遊人提供所需的通道。 for maintenance and visitations. 東華義莊於1899年建立,前身相信是位於堅尼 Tung Wah Coffin Home was established in 1899. It is believed that the predecessor 地城牛房附近的義莊,由上環文武廟於1875年 of the Tung Wah Coffin Home was a coffin home near the slaughterhouse in Kennedy 出資建成,後來交由東華醫院管理。1899年, Town established in 1875 with funds from the Man Mo Temple in Sheung Wan. The 政府批出大口環一幅土地重建義莊,正式命名為 management of the coffin home was later handed over to Tung Wah Hospital. -

The Evolution of Chinese Graves at Burnaby's Ocean View Cemetery: from Stigmatized Purlieu to Political Adaptations and Cultural Identity

The Evolution of Chinese Graves at Burnaby's Ocean View Cemetery: From Stigmatized Purlieu to Political Adaptations and Cultural Identity by Maurice Conrad Guibord B.A. (Archaeology), University of Calgary, 1981 B.A. (Hons., Translation), University of Ottawa, 1977 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Maurice Conrad Guibord 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2013 Approval Name: Maurice Conrad Guibord Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title of Thesis: The Evolution of Chinese Graves at Burnaby's Ocean View Cemetery: From Stigmatized Purlieu to Political Adaptations and Cultural Identity Examining Committee: Chair: Roxanne Panchasi Graduate Chair, Associate Professor Nicolas Kenny Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor Jeremy Brown Supervisor Assistant Professor David Chuenyen Lai External Examiner Professor Department of Geography University of Victoria Date Defended/Approved: September 19, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement iv Abstract This thesis analyzes the practice of racism against the Chinese community in Vancouver-area cemeteries, and how it was modified by trans-Pacific political and cultural forces. It shows how, at Burnaby's Ocean View cemetery, the Chinese community moved away from segregation in the burial place and progressed to burial designs that responded to its cultural and religious needs. It analyzes the abandonment by some Chinese immigrants of their tradition of disinterment and repatriation to China, when they chose to be buried there rather than at Vancouver's Mountain View cemetery. It also argues that the Chinese community of the Lower Mainland modified its own burial traditions in a manner different from anywhere else in B.C., as a result of the wave of immigrants from Hong Kong in the 1980s-90s. -

Decolonizing My Hong Kong Identity As a Settler in Canada: an Expressive Arts-Based Inquiry

Creative Arts Educ Ther (2020) 6(2):153–170 DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2020/6/22 Decolonizing my Hong Kong Identity as a Settler in Canada: An Expressive Arts-based Inquiry 表達藝術本位研究: 從加拿大遷佔者到香港去殖民化身份認同 Gracelynn Chung-yan Lau Queen’s University, Canada Abstract This paper documents an intermodel arts-based inquiry through engaging in expressive arts ther- apy. The author responded to reflexive questions: Who am I as a Hong Kong Chinese Canadian in the indigenous-colonial context of the 21st century? How can I carry my own decolonization through the arts? Carried out in Hong Kong and Ontario, Canada, this inquiry explored indigene- ity, settler colonialism, personal and collective history, and family memories. Keywords: settler colonialism, decolonize identity, expressive arts-based inquiry, Indigenous-settler rela- tions, cultural healing 摘要 作者以表達藝術治療的方法論進行藝術本位研究 (art-based inquiry),探討自身作為加 拿大遷佔者(settler) 與香港去殖民化的身份認同,在「原住民 – 殖民者」(indigenous- colonial) 的脈絡下反思加拿大香港移民身份,探討如何透過表達藝術治療深化去殖民 化的身份認同。本文記錄作者在香港及加拿安大略省為期三個月的藝術本位研究過程, 思考原住民性、遷佔殖民主義、個人與集體歷史,以及家族記憶。 關鍵詞: 遷佔殖民主義,身份去殖民化,表達藝術本位研究,原住民—遷佔者關係,文化療癒 Introduction This inquiry sprang from questioning my positionality as a Hong Kong Chinese Canadian in the indigenous-colonial context of the 21st century Canada, and what are my responsibilities as a researcher working with indigenous peoples in British Columbia. I started out searching for an appropriate indigenous research methodology that I could work from to carry out my doctoral research project. But when reading indigenous pedagogies and methodologies, I realized that the emerging indigenous research paradigms are a collective endeavor of many indigenous scholars, who frame research through their own ontological and epistemological foundations and methods, with the intention of creating space for more indigenous scholars to thrive in the Western dominant academic setting. -

Board Paper AAB/17/2019-20

Circulation Deadline BOARD PAPER on 12 March 2020 AAB/17/2019-20 MEMORANDUM FOR THE ANTIQUITIES ADVISORY BOARD DECLARATION OF THREE HISTORIC ITEMS AS MONUMENTS PURPOSE This paper seeks Members’ advice on the proposal to declare the following three items as monuments under section 3(1) of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) (the “Ordinance”): (a) Masonry Bridge of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir (薄扶林水塘石橋), Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong; (b) Tung Wah Coffin Home (東華義莊), Sandy Bay Road, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong; and (c) Tin Hau Temple and the adjoining buildings, Yau Ma Tei (油麻地天 后古廟及其鄰接建築物), Kowloon. HERITAGE VALUE Masonry Bridge of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir 2. Pok Fu Lam Reservoir is the first public reservoir in Hong Kong. The construction of the reservoir commenced in 1860 and water supplies to the city began at the end of 1863. Several extensions were undertaken between 1866 and 1877. Prior to the construction of Tai Tam Reservoir in the 1880s, Pok Fu Lam Reservoir was the only reservoir providing fresh water supplies to the Central and Western Districts. 3. The Masonry Bridge is one of the oldest surviving historic structures of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir. The bridge is situated at the east end of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir and carries Pok Fu Lam Reservoir Road, which runs along the northern 2 side of the reservoir. It spans the mouth of one of the feeder streams that run off the surrounding hillsides. The bridge is built of granite and features an elegant semi-circular arch. It is neatly finished with granite copings with chamfered margins and reticulated surfaces. -

From Canton, Hong Kong, to Victoria and Barkerville

Kwong Lee & Company and Early Trans-Pacific Trade: From Canton, Hong Kong, to Victoria and Barkerville Tzu-I Chung* The gold seekers were harbingers of modernity, and one had to be rather modern in 1850 to be untroubled by the world they seem to foreshadow, to be sure that a society dominated by self-interested, wealth-seeking men would be worth living in.1 he nineteenth-century gold rushes played a key role not only in shaping British Columbia but also in starting “the Pacific century” and transforming the Pacific from a peripheral zone Tinto “a nexus of world trade.”2 Gold seekers from many parts of Europe, the Americas, and Asia followed the gold trail around the Pacific Rim. Even if few gold seekers became wealthy, the increased supply of gold stimulated global trade and investment and brought profits to some merchants engaged in the trans-Pacific trade.3 The gold rush initiated the first major Chinese settlement in what is now British Columbia. After the news of gold in the Fraser Canyon broke in 1858 and Billy Barker struck gold in the Cariboo in 1862, Victoria, New Westminster, * Special thanks to Judy Campbell, Ying-ying Chen, Bill Quackenbush, Mandy Kilsby, everyone at the Barkerville Symposium in June 2012, including special issue editor Jacqueline Holler, Lily Chow, Robert Griffin, David Chuenyan Lai, Elizabeth Sinn, Lorne Hammond, Chuimei Ho, Ben Bronson, and Henry Yu, the anonymous reviewers, and the staff at Barkerville Historic Town, the Royal BC Museum, and the British Columbia Archives (hereafter bca). Much deep appreciation to Richard Mackie, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. -

Coffin Home 15/11

! !"#$%&'()*+,-!./012-34. !"#$%&'()*+,-./012/34 5678 !"#$%&'()*+,-./01234567890( !"#$%&'()*+,-./01234567 !" = !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456 !"#$%&'()*+,-./012*345!6"78 !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:; ! "#$%&'()*+,-.*/0#123456-7 !"#$%&'()*+,-./!012345 !67, ! !"# !"#$%&&'()*+,*-"#./012342 !"#$%&'()*+,-./01 2345678!" !"#$%&'()*+,-$%./01234567 !"#$%&'()*+,#-./%012345%67 !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123"4567 !"#$"%& !" !"#$%&'()*+,-./012345678 !"#$%&'()*+,-./!012*345678 !"#$%&'()*+,-./012345678&9: !"#$%&'()*+,-./01234 56789: !"#$%&'()*+,-./012345678 !"#$%&'()*+,-./012345/67$8 !"#$%&'()!* !"#$%&'()*+,-./01234%&5 !"#$%&'()*+, ==qÜÉ=kÉï=e~ää ! !"#$%&'()*+,-$./*01234567$892 ! ! !"#"$%&' !"#$%&' !"#$%&'( !"#$%&'()*+&'&,*-%./01!23456789 !" !"#$%&'()*+,-./01234565789:;/< !"#$%&' ()*+, -./012345678&9:;< !""#$%&'()#$*+""#,-./0123456789: !"#$!% &'()*+,-./012 !" !"#$%!"&'()*+,-.!"//012&345%67 !"#$%&'()*+,-./01-.2345567&89:; !"#$%&$'()*+,-./0123456789:;< !"#$ !"# !"#$%&&'%() !"#$% !"#$%&'()*+,-./0 12345.62789: !"#$%&'()*+,- ./012345$6789::;< !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<1=> !"#$%&'()*+,-&./01"234567"89:; !"#$%&'() !*+,-./01234562789:; !"#$%&'()* +,#-./00123-456 !"#$%&'()*"+,-./0123456)*7806 !"#$%&'(")*+,-./01#$%&234567&89 !"#$%&'()*+,-./012'(3456789:;<= !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789&':56% !"#$%&'() *+,-./012345678459(:6+ !"#$%&'()*+,-./012345675895:;<= !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>? !"#$%&'()*+,-./012, !34"567 !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@AB !" ==eçå=C=káåÖ=oççãë ==Comments from the adjudicators !"# The Antiquities -

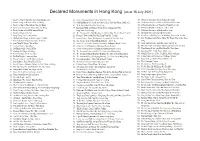

Declared Monuments in Hong Kong As at 22 May 2020

Declared Monuments in Hong Kong (as at 16 July 2021) 1. Rock Carving at Big Wave Bay, Hong Kong Island 45. Former Kowloon British School, Tsim Sha Tsui 87. 6 Historic Structures of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir 2. Rock Carving on Kau Sai Chau, Sai Kung 46. Main Building of St. Stephen's Girls' College, Lyttelton Road, Mid-Levels 88. 22 Historic Structures of Tai Tam Group of Reservoirs 3. Rock Carving on Tung Lung Chau, Sai Kung 47. Yi Tai Study Hall, Kam Tin, Yuen Long 89. 3 Historic Structures of Wong Nai Chung Reservoir 4. Rock Inscription at Joss House Bay, Sai Kung 48. Enclosing Walls and Corner Watch Towers of Kun Lung Wai, 90. 4 Historic Structures of Aberdeen Reservoir 5. Rock Carving at Shek Pik, Lantau Island Lung Yeuk Tau, Fanling 91. 5 Historic Structures of Kowloon Reservoir 6. Rock Carvings on Po Toi 49. The Exterior of the Main Building, the Helena May, Garden Road, Central 92. Memorial Stone of Shing Mun Reservoir 7. Tung Chung Fort, Lantau Island 50. Entrance Tower of Ma Wat Wai, Lung Yeuk Tau, Fanling 93. Residence of Ip Ting-sz at Lin Ma Hang Tsuen, Sha Tau Kok 8. Duddell Street Steps and Gas Lamps, Central 51. Former Marine Police Headquarters Compound, Tsim Sha Tsui 94. Yan Tun Kong Study Hall at Hang Tau Tsuen, Ping Shan, Yuen 9. Tung Lung Fort, Tung Lung Chau, Sai Kung 52. Gate Lodge of the Former Mountain Lodge, the Peak Long 10. Sam Tung Uk Village, Tsuen Wan 53. Former Central Police Station Compound, Hollywood Road, Central 95.