Henry Yu (University of British Columbia) and Elizabeth Sinn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Board Paper AAB/17/2019-20 (Annex C)

Heritage Appraisal of Tin Hau Temple Annex C and the adjoining buildings, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon Tin Hau Temple and the adjoining buildings (the “Temple Historical Compound”) in Yau Ma Tei are significant in the history of Kowloon as Interest a multi-functional place of worship, arbitration and study. The compound comprises five buildings, namely Tin Hau Temple (天后古 廟 ), Kung Sor (公所) (Communal Hall) (now Kwun Yam Lau She Tan 觀音樓社壇), Fook Tak Tsz (福德祠) (now Kwun Yam Temple 觀音 古廟) and the two Shu Yuen (書院) (Schools) (now a Shing Wong Temple 城隍廟 and exhibition centre). The Temple Compound is so well known that the neighbouring Temple Street is also named after it. It was initially administered by a temple management committee (天 后 廟 值 理 會 ) formed by local merchants and residents. Its management was officially delegated to Kwong Wah Hospital1 by the Chinese Temples Committee (華人廟宇 委 員 會 ) in 19282 . The operating surplus of the Temple Compound was not only used by Kwong Wah Hospital to build the new labour room and to repay Tung Wah Hospital’s previous loans, but also served to finance the charitable services of the later Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs). The Tin Hau Temple, which was the first building constructed within the compound, replaced an earlier Tin Hau Temple probably built in 1865 by the local community at around the junction of today’s Pak Hoi Street and Temple Street3. According to the inscription on the granite 1 Tung Wah Hospital, Kwong Wah Hospital and Tung Wah Eastern Hospital were amalgamated into a single entity, and the name “Tung Wah Group of Hospitals” (TWGHs) was adopted. -

The Plague of Hong Kong in 1894 Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Colonialism versus Nationalism: The Plague of Hong Kong in Title 1894 Author(s) Lee, PT The Journal of Northeast Asian History, 2013, v. 10 n. 1, p. 97- Citation 128 Issued Date 2013 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/185180 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License Colonialism versus Nationalism: The Plague of Hong Kong in 1894 Pui-Tak Lee Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong The Journal of Northeast Asian History Volume 10 Number 1 (Summer 2013), 97-128 Copyright © 2013 by the Northeast Asian History Foundation. All Rights Reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the Northeast Asian History Foundation. Colonialism versus Nationalism: The Plague of Hong Kong in 1894 Drawing upon different source materials, this paper examines the significance of the plague of Hong Kong in 1894 in two ways. Firstly, it shows the process by which the colonial power successfully implemented the public health policy in Hong Kong by collaborating with the local Chinese communities. Secondly, it demonstrates how the Chinese in Hong Kong responded to the colonial mandatory measures by resisting them or partially accepting them. This paper highlights the reactions of the Chinese towards the prevention measures implemented by the British, and the controversy about the effectiveness of Chinese and western medicine in safeguarding public health. Keywords: Hong Kong plague, colonialism, Aoyama-Kitasato-Yersin controversy, Tung Wah Hospital, Chinese and Western medicine Colonialism versus Nationalism: The Plague of Hong Kong in 1894 Pui-Tak Lee Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong I. -

List of Medical Equipment Required by Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (2010/2011)

List of Medical Equipment Required by Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (2010/2011) Tung Wah Hospital No. of Name of Quantity Unit cost No. Function patient-cases medical equipment required (HK$) served A1 High Definition To enhance the efficiency and accuracy of diagnosis 700/year 1 295,463 Colono Videoscope directly for examination of colon and sigmoid diseases as equipped with high definition CCD. A2 Choledocho To examine patients’ common bile duct and gall bladder 100/year 1 156,566 Videoscope system directly. A3 Flexible To investigate bladder and urethra of patients and be More than 1 153,162 Cystovideoscope capable of producing high quality magnified images 1,000/year which directly enhance the efficiency and accuracy of disease diagnosis as equipped with high resolution of CCD. A4 Haemodiaylsis To support life-of-end stage renal disease patients by More than 2 130,000 Machine removing uremic toxins and excessive fluid, and 1,000/year correcting serum electrolyte disorder. Every patient normally receives 2 to 3 treatments a week and each treatment lasts for 5 to 6 hours. A5 Ventilator To provide continuous respiratory support to critically ill For whole 2 130,000 and motor neuron disease patients. year A6 Nerve Monitor To give an audible interpretation of muscle activity 100/year 1 105,000 which is sensed by needle electrodes placed into the relevant muscle groups and to monitor facial nerve and recurrent laryngeal nerve for safe surgery for mastoid, parotid and thyroid diseases. A7 Manipulating To reduce operative time and to enhance the accuracy of 20/year 1 96,000 System for the fixation of fracture by allowing better exposure and Facial and manipulation of complex facial fracture, which can be Mandibular Fracture corrected with operative fixation, leading to early and Reconstruction recovery of patients and better functional outcomes. -

Hospital Authority Special Visiting Arrangement in Hospitals/Units with Non-Acute Settings Under Emergency Response Level Notes to Visitors

Hospital Authority Special Visiting Arrangement in Hospitals/Units with Non-acute Settings under Emergency Response Level Notes to Visitors 1. Hospital Authority implemented special visiting arrangement in four phases on 21 April 2021, 29 May 2021, 25 June 2021 and 23 July 2021 respectively (as appended table). Cluster Hospitals/Units with non-acute settings Cheshire Home, Chung Hom Kok Ruttonjee Hospital Hong Kong East Mixed Infirmary and Convalescent Wards Cluster Tung Wah Eastern Hospital Wong Chuk Hang Hospital Grantham Hospital MacLehose Medical Rehabilitation Centre Hong Kong West The Duchess of Kent Children’s Hospital at Sandy Bay Cluster Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Fung Yiu King Hospital Tung Wah Hospital Kowloon East Haven of Hope Hospital Cluster Hong Kong Buddhist Hospital Kowloon Central Kowloon Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Cluster Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Wong Tai Sin Hospital Caritas Medical Centre Developmental Disabilities Unit, Wai Yee Block Medical and Geriatrics/Orthopaedics Rehabilitation Wards and Palliative Care Ward, Wai Ming Block North Lantau Hospital Kowloon West Extended Care Wards Cluster Princess Margaret Hospital Lai King Building Yan Chai Hospital Orthopaedics and Traumatology Rehabilitation Ward and Medical Extended Care Unit (Rehabilitation and Infirmary Wards), Multi-services Complex New Territories Bradbury Hospice East Cluster Cheshire Home, Shatin North District Hospital 4B Convalescent Rehabilitation Ward Shatin Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Tai Po Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Pok Oi Hospital Tin Ka Ping Infirmary New Territories Siu Lam Hospital West Cluster Tuen Mun Hospital Rehabilitation Block (Except Day Wards) H1 Palliative Ward 2. Hospital staff will contact patients’ family members for explanation of special visiting arrangement and scheduling the visits. -

(Cap. 53) Antiquities and Monuments (Declaration of Monuments and Historical Buildings) (Consolidation) (Amendment) Notice 2020

File Ref.: DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/141 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) Antiquities and Monuments (Declaration of Monuments and Historical Buildings) (Consolidation) (Amendment) Notice 2020 INTRODUCTION After consultation with the Antiquities Advisory Board (“AAB”)1 and with the approval of the Chief Executive, the Secretary for Development (“SDEV”), in his capacity as the Antiquities Authority under the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) (the “Ordinance”), has decided to declare three historic items, i.e. the masonry bridge of Pok Fu Lam Reservoir (薄扶林水塘石橋), Tung Wah Coffin Home (東華義莊) and Tin Hau Temple and the adjoining buildings (天后古廟及其鄰接建築物), as monuments2 under section 3(1) of the Ordinance. 2. The declaration is made by the Antiquities and Monuments (Declaration of Monuments and Historical Buildings) (Consolidation) A (Amendment) Notice 2020 (the “Notice”) (Annex A), which will be published in the Gazette on 22 May 2020. 1 The Antiquities Advisory Board is a statutory body established under section 17 of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) to advise the Antiquities Authority on any matters relating to antiquities, proposed monuments or monuments or referred to it for consultation under sections 2A(1), 3(1) or 6(4) of the Ordinance. 2 Under section 2 of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53), “monument” (古蹟) means a place, building, site or structure which is declared to be a monument, historical building or archaeological or palaeontological site or structure. JUSTIFICATIONS Heritage Significance 3. The Antiquities and Monuments Office (“AMO”)3 has carried out research on and assessed the heritage significance of the three historic items set out in paragraph 1 above. -

Hospital Authority List of Medical Social Services Units (January 2019)

Hospital Authority List of Medical Social Services Units (January 2019) Name of Hospital Address Tel No. Fax No. 1. Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole 11 Chuen On Road, Tai Po, N.T. 2689 2020 2662 3152 Hospital (Non- psychiatric medical social service) 2. Bradbury Hospital 17 A Kung Kok Shan Road, 2645 8832 2762 1518 Shatin, N.T. 3. Caritas Medical Centre 111 Wing Hong Street, 3408 7709 2785 3192 Shamshuipo, Kowloon 4. Cheshire Home 128 Chung Hom Kok Road, 2899 1391 2813 8752 (Chung Hom Kok) Hong Kong 5. Cheshire Home (Shatin) 30 A Kung Kok Shan Road, 2636 7269 2636 7242 Shatin, N.T. 6. TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital 9 Sandy Bay Road, Hong Kong 2855 6236 2904 9021 7. Grantham Hospital 125 Wong Chuk Hang Road, 2518 2678 2580 7629 Aberdeen, Hong Kong 8. Haven of Hope Hospital 8 Haven of Hope Road, 2703 8227 2703 8230 Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon 9. Hong Kong Buddhist Hospital 10 Heng Lam Road, Lok Fu, 2339 6253 2339 6298 Kowloon 10. Kowloon Hospital Mezzanine Floor, Kowloon 3129 7806/ 3129 7838 (Ward 2B at Rehabilitation Hospital Rehabilitation Building, 3129 7831 Building ) 147A, Argyle Street, Kowloon 11. Kwong Wah Hospital 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 3517 2900 3517 2959 12. MacLehose Medical 7 Sha Wan Drive, 2872 7131 2872 7909 Rehabilitation Centre Pokfulam, Hong Kong Name of Hospital Address Tel No. Fax No. 13. Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital 118 Shatin Pass Road, 2354 2285 2324 8719 Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon 14. Pok Oi Hospital Au Tau, Yuen Long, N.T. 2486 8140 2486 8095 2486 8141 15. -

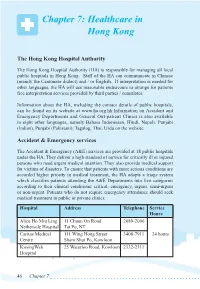

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong The Hong Kong Hospital Authority The Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA) is responsible for managing all local public hospitals in Hong Kong. Staff of the HA can communicate in Chinese (mainly the Cantonese dialect) and / or English. If interpretation is needed for other languages, the HA will use reasonable endeavours to arrange for patients free interpretation services provided by third parties / consulates. Information about the HA, including the contact details of public hospitals, can be found on its website at www.ha.org.hk.Information on Accident and Emergency Departments and General Out-patient Clinics is also available in eight other languages, namely Bahasa Indonesian, Hindi, Nepali, Punjabi (Indian), Punjabi (Pakistani), Tagalog, Thai, Urdu on the website. Accident & Emergency services The Accident & Emergency (A&E) services are provided at 18 public hospitals under the HA. They deliver a high standard of service for critically ill or injured persons who need urgent medical attention. They also provide medical support for victims of disasters. To ensure that patients with more serious conditions are accorded higher priority in medical treatment, the HA adopts a triage system which classifies patients attending the A&E Departments into five categories according to their clinical conditions: critical, emergency, urgent, semi-urgent or non-urgent. Patients who do not require emergency attendance should seek medical treatment in public or private clinics. Hospital Address Telephone Service Hours Alice Ho Miu Ling 11 Chuen On Road 2689-2000 Nethersole Hospital Tai Po, NT Caritas Medical 111 Wing Hong Street 3408-7911 24 hours Centre Sham Shui Po, Kowloon KwongWah 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 2332-2311 Hospital 46 Chapter 7 North District 9 Po Kin Road 2683-8888 Hospital Sheung Shui, NT North Lantau 1/F, 8 Chung Yan Road 3467-7000 Hospital Tung Chung, Lantau, N.T. -

Glossary of Place Names for the Chinese Australian Hometown Heritage Tour, March 2017

Glossary of place names for the Chinese Australian Hometown Heritage Tour, March 2017 Chinese English name or characters Mandarin (pinyin) Cantonese (Yale) ‘Chinese postal romanisation’ (traditional) HONG KONG Hong Kong 香港 Xiānggǎng Hēunggóng Tsim Sha Tsui (TST) 尖沙嘴 Jiānshāzuǐ Jīmsājéui Pokfulam 薄扶林 Bófúlín Bohkfùhlàhm Tung Wah Coffin Home 東華義莊 Dōnghuá yìzhuāng Dūngwah yihjōng Hong Kong China Ferry Terminal 中港碼頭 Zhōnggǎng mǎtóu Jūnggóng máhtàuh GUANGDONG Canton [province], Kwangtung 廣東 Guǎngdōng Gwóngdūng Canton [city], Kwangchow (Foo) 廣州(府) Guǎngzhōu(fǔ) Gwóngjāu(fú) Pearl River Delta 珠江三角洲 Zhūjiāng sānjiǎo zhōu Jyūgōng sāamgok jāu Sze Yap, See Yup, Four Counties 四邑 Sìyì Seiyāp Wuyi, Five Counties 五邑 Wǔyì Ńghyāp Sam Yap, Three Counties 三邑 Sānyì Sāamyāp JIANGMEN Kongmoon, Jiangmen 江門 Jiāngmén Gōngmùhn Jiangmen Port 江門港 Jiāngméngǎng Gōngmùhngóng Xi River, West River 西江 Xījiāng Sāigōng Jiāngmén Wǔyì Gōngmùhn Ńghyāp Wuyi Museum of Overseas Chinese, 江門五邑華僑 huàqiáo huàrén wahkìuh wahyàhn Jiangmen Museum 華人博物馆 bówùguǎn bokmahtgún Ńghyāp daaihhohk 五邑大學中國 Wǔyì dàxué Zhōngguó Wuyi University Overseas Chinese Jūnggwok kìuhhēung 僑鄉文化研究 qiáoxiāng wénhuà Culture Research Centre màhnfa yìhngau 中心 yánjiù zhōngxīn jūngsām Pengjiang 蓬江 Péngjiāng Fùhnggōng KAIPING Hoiping, Kaiping 開平 Kāipíng Hōipèhng Kaiping diaolou 開平碉樓 Kāipíng diāolóu Hōipèhng dīulàuh Tangkou 塘口 Tángkǒu Tòhngháu Cangdong 倉東 Cāngdōng Chōngdūng Cangdong Heritage Education Chōngdūng gāauyuhk 倉東教育基地 Cāngdōng jiàoyu jīdì Centre gēideih Li Yuan, Li Garden 立園 Lìyuán Laahpyùhn Glossary of place -

Zhang Da Fo Ye (Zhang Qishan)—Unknown 2

1 Grave Robbers’ Chronicles: The Mystic Nine Written by: Xu Lei Translated by: Tiffany X and Merebear Edited by: Merebear 2 Summary: During the Republic Era, the town of Changsha was guarded by nine families known as the “Old Nine Gates” (or the “Mystic Nine”). They were incredibly powerful families who wielded supreme power over everything in Changsha. In 1933, a mysterious train pulled into Changsha station. The leader of the Nine Gates, Zhang Qishan, was also the army commander of Changsha station and started to investigate with Qi Tiezui. They discovered a highly suspicious mine just outside of Changsha. 3 The Mystic Nine Vol. 1 4 Introduction: About the Mystic Nine The Mystic Nine refers to the nine tomb-robbing families in old Changsha, which are often mentioned in the tomb-robbing notes. They consist of the upper three clans, middle three clans, and lower three clans respectively. Upper Three Clans: 1. Zhang Da Fo Ye (Zhang Qishan)—unknown 2. Er Yuehong—has three sons and taught Chen Pi Ah Si and Xiao Hua 3. Banjie Li—Li Sidi (guess) Middle Three Clans: 4. Chen Pi Ah Si—Chen Wen-Jin 5. Old Dog Wu, Fifth Master Dog—Wu Yiqiong, Wu Erbai, Wu Sanxing— Wu Xie 6. Black Back the Sixth—the only one in the Nine Gates without any offspring Lower Three Clans: 7. Huo Xiangu, Madam Seven—Huo Ling—Huo Xiuxiu 8. Qimen Fortune Teller Qi Tiezui the Eighth—Qi Yu (guess) 9. Xiao Xiejiu—Xie Lianhuan (Xiao Hua’s uncle) and Xiao Hua’s father— Xie Yuchen/Xie Yuhua (aka, Xiao Hua) Those who participated in the archaeological activity in Xisha were Zhang Qiling, Li Sidi, Chen Wen-Jin, Wu Sanxing, Huo Ling, Qi Yu, and Xie Lianhuan, whose surnames are “Zhang, Li, Chen, Wu, Huo, Qi, and Xie”. -

Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital

Heritage Impact Assessment for Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR TUNG WAH MUSEUM In Respect of THE REDEVELOPMENT OF KWONG WAH HOSPITAL PREPARED FOR HOSPITAL AUTHORITY I TUNG WAH GROUP OF HOSPITALS I KWONG WAH HOSPITAL ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT SIMON KWAN & ASSOCIATES LTD. HERITAGE CONSERVATION CONSULTANT URBANAGE INTERNATIONAL LTD. May 2015 Heritage Impact Assessment for Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 1.2 Site Location 1.3 Objectives and Scope of Heritage Impact Assessment 1.4 Methodology 1.5 Acknowledgements 1.6 Definitions 2.0 HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL APPRAISAL 2.1 Historical Development 2.2 Founding of Kwong Wah Hospital 2.3 Redevelopment of 1950s-1960s 2.4 Conversion to Tung Wah Museum 2.5 Chronological Events 2.6 Architectural Appraisal 2.6.1 Study Area 2.6.2 General Description of the Existing Buildings 2.6.3 Tung Wah Museum 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE VALUE 3.1 Cultural Significance 3.2 Statement of Cultural Significance 3.3 Character Defining Elements 3.3.1 External Elements 3.3.2 Internal Elements Heritage Impact Assessment for Tung Wah Museum Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital 4.0 CONSERVATION POLICIES 4.1 Conservation Objectives 4.2 Conservation Principles 5.0 REDEVELOPMENT SCHEME 5.1 Design Options 5.2 Design Principles Adopted in Option 3C 5.3 Latest Proposed Scheme for the Redevelopment 6.0 ASSESSMENT OF IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES 6.1 Potential Impacts 6.2 Mitigation Measures 6.3 Enhancement -

List of the 1444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results

List of the 1,444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results (as at 9 Sept 2021) Page 1 Proposed Year of Construction / Remarks Number Name and Address 名稱及地址 Ownership Grading Restoration 備註 Grade 1 confirmed on 18 Dec 2009 Tsang Tai Uk, Sha Tin, N.T. 新界沙田曾大屋 1 Private Built 1847-1867 1 二○○九年十二月十八日確定為一級歷史建築 Combined with numbers 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with The Wai was built between Kat Hing Wai, Shrine, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍神廳 1 Private 1465 and 1487, the wall 2 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號3、4、5、6和7合併為一項, N.T. was 1662-1722. 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Entrance Gate, Kam Tin, 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 3 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍圍門 1 Private Yuen Long, N.T. was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、4、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northwest) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 4 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. (西北)及圍牆 was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、3、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northeast) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 5 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T.