Deception with Technology Jeffrey T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threat Defense: Cyber Deception Approach and Education for Resilience in Hybrid Threats Model

S S symmetry Article Threat Defense: Cyber Deception Approach and Education for Resilience in Hybrid Threats Model William Steingartner 1,* , Darko Galinec 2 and Andrija Kozina 3 1 Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Technical University of Košice, Letná 9, 042 00 Košice, Slovakia 2 Department of Informatics and Computing, Zagreb University of Applied Sciences, Vrbik 8, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 3 Dr. Franjo Tudman¯ Croatian Defence Academy, 256b Ilica Street, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper aims to explore the cyber-deception-based approach and to design a novel conceptual model of hybrid threats that includes deception methods. Security programs primarily focus on prevention-based strategies aimed at stopping attackers from getting into the network. These programs attempt to use hardened perimeters and endpoint defenses by recognizing and blocking malicious activities to detect and stop attackers before they can get in. Most organizations implement such a strategy by fortifying their networks with defense-in-depth through layered prevention controls. Detection controls are usually placed to augment prevention at the perimeter, and not as consistently deployed for in-network threat detection. This architecture leaves detection gaps that are difficult to fill with existing security controls not specifically designed for that role. Rather than using prevention alone, a strategy that attackers have consistently succeeded against, defenders Citation: Steingartner, W.; are adopting a more balanced strategy that includes detection and response. Most organizations Galinec, D.; Kozina, A. Threat Defense: Cyber Deception Approach deploy an intrusion detection system (IDS) or next-generation firewall that picks up known attacks and Education for Resilience in or attempts to pattern match for identification. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Cues to Deception

Psychological Bulletin Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2003, Vol. 129, No. 1, 74–118 0033-2909/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.74 Cues to Deception Bella M. DePaulo James J. Lindsay University of Virginia University of Missouri—Columbia Brian E. Malone Laura Muhlenbruck, Kelly Charlton, and University of Virginia Harris Cooper University of Missouri—Columbia Do people behave differently when they are lying compared with when they are telling the truth? The combined results of 1,338 estimates of 158 cues to deception are reported. Results show that in some ways, liars are less forthcoming than truth tellers, and they tell less compelling tales. They also make a more negative impression and are more tense. Their stories include fewer ordinary imperfections and unusual contents. However, many behaviors showed no discernible links, or only weak links, to deceit. Cues to deception were more pronounced when people were motivated to succeed, especially when the motivations were identity relevant rather than monetary or material. Cues to deception were also stronger when lies were about transgressions. Do people behave in discernibly different ways when they are Zuckerman, DePaulo, & Rosenthal, 1986; Zuckerman & Driver, lying compared with when they are telling the truth? Practitioners 1985), but the number of additional estimates was small. Other and laypersons have been interested in this question for centuries reviews have been more comprehensive but not quantitative (see (Trovillo, 1939). The scientific search for behavioral cues to Vrij, 2000, for the most recent of these). In the present review, we deception is also longstanding and has become especially vigorous summarize quantitatively the results of more than 1,300 estimates in the past few decades. -

Rptr Bryant Edtr Rosen Americans at Risk

1 RPTR BRYANT EDTR ROSEN AMERICANS AT RISK: MANIPULATION AND DECEPTION IN THE DIGITAL AGE WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 8, 2020 House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Washington, D.C. The subcommittee met, pursuant to call, at 10:32 a.m., in Room 2123, Rayburn House Office Building, Hon. Jan Schakowsky [chairwoman of the subcommittee] presiding. Present: Representatives Schakowsky, Castor, Veasey, Kelly, O'Halleran, Lujan, Cardenas, Blunt Rochester, Soto, Matsui, McNerney, Dingell, Pallone (ex officio), Rodgers, Burgess, Latta, Guthrie, Bucshon, Hudson, Carter, and Walden (ex officio). Staff Present: Jeff Carroll, Staff Director; Evan Gilbert, Deputy Press Secretary; Lisa Goldman, Senior Counsel; Waverly Gordon, Deputy Chief Counsel; Tiffany Guarascio, 2 Deputy Staff Director; Alex Hoehn-Saric, Chief Counsel, Communications and Consumer Protection; Zach Kahan, Outreach and Member Service Coordinator; Joe Orlando, Staff Assistant; Alivia Roberts, Press Assistant; Chloe Rodriguez, Policy Analyst; Sydney Terry, Policy Coordinator; Anna Yu Professional Staff Member; Mike Bloomquist, Minority Staff Director; S.K. Bowen, Minority Press Assistant; William Clutterbuck, Minority Staff Assistant; Jordan Davis, Minority Senior Advisor; Tyler Greenberg, Minority Staff Assistant; Peter Kielty, Minority General Counsel; Ryan Long, Minority Deputy Staff Director; Mary Martin, Minority Chief Counsel, Energy & Environment & Climate Change; Brandon Mooney, Minority Deputy Chief Counsel, Energy; Brannon Rains, Minority Legislative Clerk; Zack Roday, Minority Communications Director; and Peter Spencer, Minority Senior Professional Staff Member, Environment & Climate Change. 3 Ms. Schakowsky. Good morning, everyone. The Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce will now come to order. We will begin with member statements, and I will begin by recognizing myself for 5 minutes. -

The Evolution and Psychology of Self-Deception

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2011) 34,1–56 doi:10.1017/S0140525X10001354 The evolution and psychology of self-deception William von Hippel School of Psychology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia [email protected] http://www.psy.uq.edu.au/directory/index.html?id¼1159 Robert Trivers Department of Anthropology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 [email protected] http://anthro.rutgers.edu/ index.php?option¼com_content&task¼view&id¼102&Itemid¼136 Abstract: In this article we argue that self-deception evolved to facilitate interpersonal deception by allowing people to avoid the cues to conscious deception that might reveal deceptive intent. Self-deception has two additional advantages: It eliminates the costly cognitive load that is typically associated with deceiving, and it can minimize retribution if the deception is discovered. Beyond its role in specific acts of deception, self-deceptive self-enhancement also allows people to display more confidence than is warranted, which has a host of social advantages. The question then arises of how the self can be both deceiver and deceived. We propose that this is achieved through dissociations of mental processes, including conscious versus unconscious memories, conscious versus unconscious attitudes, and automatic versus controlled processes. Given the variety of methods for deceiving others, it should come as no surprise that self-deception manifests itself in a number of different psychological processes, and we discuss various types of self-deception. We then discuss the interpersonal versus intrapersonal nature of self-deception before considering the levels of consciousness at which the self can be deceived. -

Lies, True Lies, and Conscious Deception 3 Not a Fixed Target

Police Quarterly OnlineFirst, published on November 17, 2008 as doi:10.1177/1098611108327315 Police Quarterly Volume XX Number X Month XXXX xx-xx © 2008 Sage Publications 10.1177/1098611108327315 Lies, True Lies, and http://pqx.sagepub.com hosted at Conscious Deception http://online.sagepub.com Police Officers and the Truth Geoffrey P. Alpert University of South Carolina Jeffrey J. Noble, Esq. Irvine, California Police Department Police officers often tell lies; they act in ways that are deceptive, they manipulative people and situations, they coerce citizens, and are dishonest. They are taught, encouraged, and often rewarded for their deceptive practices. Officers often lie to suspects about witnesses and evidence, and they are deceitful when attempting to learn about criminal activity. Most of these actions are sanctioned, legal, and expected. Although they are allowed to be dishonest in certain circumstances, they are also required to be trustworthy, honest, and maintain the highest level of integrity. The purpose of this article is to explore situations when officers can be dishonest, some reasons that help us understand the dishonesty, and circumstances where lies may lead to unintended consequences such as false confessions. The authors conclude with a discussion of how police agencies can manage the lies that officers tell and the consequences for the officers, organizations, and the criminal justice system. Keywords: police deception; lies; investigations; ethics o perform their job effectively, police officers lie. They use deception, manipu- Tlation, and coercion to obtain important information from suspects. Police offi- cers often tell those suspected of committing crimes that they possess physical evidence implicating the suspect when no such evidence exists. -

Kevin Mitnick and I Were Intensely Curious About the World and Eager to Prove Ourselves

Scanned by kineticstomp THE ART OF DECEPTION Controlling the Human Element of Security KEVIN D. MITNICK & William L. Simon Foreword by Steve Wozniak For Reba Vartanian, Shelly Jaffe, Chickie Leventhal, and Mitchell Mitnick, and for the late Alan Mitnick, Adam Mitnick, and Jack Biello For Arynne, Victoria, and David, Sheldon,Vincent, and Elena. Social Engineering Social Engineering uses influence and persuasion to deceive people by convincing them that the social engineer is someone he is not, or by manipulation. As a result, the social engineer is able to take advantage of people to obtain information with or without the use of technology. Contents Foreword Preface Introduction Part 1 Behind the Scenes Chapter 1 Security's Weakest Link Part 2 The Art of the Attacker Chapter 2 When Innocuous Information Isn't Chapter 3 The Direct Attack: Just Asking for it Chapter 4 Building Trust Chapter 5 "Let Me Help You" Chapter 6 "Can You Help Me?" Chapter 7 Phony Sites and Dangerous Attachments Chapter 8 Using Sympathy, Guilt and Intimidation Chapter 9 The Reverse Sting Part 3 Intruder Alert Chapter 10 Entering the Premises Chapter 11 Combining Technology and Social Engineering Chapter 12 Attacks on the Entry-Level Employee Chapter 13 Clever Cons Chapter 14 Industrial Espionage Part 4 Raising the Bar Chapter 15 Information Security Awareness and Training Chapter 16 Recommended Corporate Information Security Policies Security at a Glance Sources Acknowledgments Foreword We humans are born with an inner drive to explore the nature of our surroundings. As young men, both Kevin Mitnick and I were intensely curious about the world and eager to prove ourselves. -

Kw Əkwáləlwət

KwƏkwálƏlwƏt “the Maiden of Deception Pass” A very long time ago, there was a house of Samish people living SAY IT: here just above the beach where there are good springs. The people “Kwuh-kwal-uhl-wut” made their living by fishing from their cedar canoes, by digging up the kwłó’ol (camas) bulbs on the hillsides, and by gathering shellfish on the rocks and the beach. This is not a “totem pole”. Totem poles w w were made by Native peoples of the North One day, K Ək álƏlwƏt and her sister were gathering chitons Pacific Coast, such as the Tsimshian, Haida, from the rocks, right here on Rosario Beach, and filling up their woven and Tlingit of British Columbia and Alaska. baskets. KwƏkwálƏlwƏt was way out on the rocks when the tide began to A totem pole is a record of lineage (family A chiton is history). It uses a relatively standardized come in. She was startled, and a chiton slipped from her hands into like an oval vocabulary of animals and people. snail with a the water. She reached down under the water to get it back. But it jointed shell. Here in the Salish Sea (Puget Sound kept rolling down deeper and deeper, out of her grasp. Finally, what You may see chitons on and Georgia Strait), Coast Salish peoples her hand touched in the dark water was not a chiton but another hand. some of the w w carved or painted the doorways and large It held her tight. K Ək álƏlwƏt tried to pull her hand free, but she rocks in this cedar posts of their houses. -

Russian Strategic Intentions

APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Russian Strategic Intentions A Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) White Paper May 2019 Contributing Authors: Dr. John Arquilla (Naval Postgraduate School), Ms. Anna Borshchevskaya (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.), Mr. Pavel Devyatkin (The Arctic Institute), MAJ Adam Dyet (U.S. Army, J5-Policy USCENTCOM), Dr. R. Evan Ellis (U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute), Mr. Daniel J. Flynn (Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI)), Dr. Daniel Goure (Lexington Institute), Ms. Abigail C. Kamp (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Roger Kangas (National Defense University), Dr. Mark N. Katz (George Mason University, Schar School of Policy and Government), Dr. Barnett S. Koven (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Jeremy W. Lamoreaux (Brigham Young University- Idaho), Dr. Marlene Laruelle (George Washington University), Dr. Christopher Marsh (Special Operations Research Association), Dr. Robert Person (United States Military Academy, West Point), Mr. Roman “Comrade” Pyatkov (HAF/A3K CHECKMATE), Dr. John Schindler (The Locarno Group), Ms. Malin Severin (UK Ministry of Defence Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC)), Dr. Thomas Sherlock (United States Military Academy, West Point), Dr. Joseph Siegle (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University), Dr. Robert Spalding III (U.S. Air Force), Dr. Richard Weitz (Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Prefaces Provided By: RDML Jeffrey J. Czerewko (Joint Staff, J39), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Editor: Ms. -

Cases Against Doctors

Cases Against Doctors This is a listing of investigations of physician registrants in which DEA was involved that resulted in the arrest and prosecution of the registrant. Last Updated: October 12, 2017 Name: Abbey, Julian A., MD City, State: Saugus, MA Date of Arrest: 10/28/2005 Date of Conviction: 04/30/2008 Judicial Status: Pled Guilty Conviction: Possession with intent to distribute DEA Registration: Revoked 03/09/2007 Remarks: Julian A. Abbey, MD, age 47, of Saugus, MA, pled guilty to possession with intent to distribute controlled substances. Abbey was sentenced to five years probation. Name: ADAMS, Lawrence, MD City, State: Phillipsburg, PA Date of Arrest: 6/12/2007 Date of Conviction: 10/31/2008 Judicial Status: Jury Conviction Conviction: Prescribing outside accepted medical treatment principles; Criminal conspiracy to obtain possession of a controlled substance by misrepresentation or fraud; Dispensing/prescribing to a drug dependent person; Refusal or failure to keep required records; Willful dispensing of a controlled substance without proper labeling; Delivery of or possession with the intent to deliver a controlled substance; Criminal use of communication facility; and Criminal conspiracy to commit delivery of or possession with the intent to deliver a controlled substance DEA Registration: Retired 07/09/2009 Remarks: Lawrence Adams, MD, age 48, of Phillipsburg, PA, was found guilty in the Court of Common Pleas of Center County, Pennsylvania of 11 counts Prescribing Outside Accepted Medical Treatment Principles; four counts -

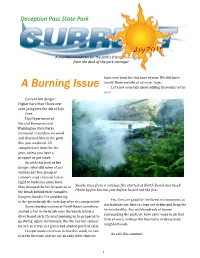

A Burning Issue Let's Not Even Talk About Adding Fireworks to the Mix! Current Fire Danger: Higher Here Than I Have Ever Seen Going Into the 4Th of July

Deception Pass State Park A monthly newsletter for the park’s friends and neighbors from the desk of the park manager have ever been for this time of year. We still have nearly three months of summer to go. A Burning Issue Let's not even talk about adding fireworks to the mix! Current fire danger: Higher here than I have ever seen going into the 4th of July. Ever. The Department of Natural Resources and Washington State Parks instituted a total ban on wood and charcoal fires in the park this past weekend. All campfires are done for the year, unless you have a propane or gas stove. So with this level of fire danger, what did some of our visitors do? One group of campers used charcoal late at night to barbecue some food, then dumped the hot briquettes in Smoke rises from a careless fire started at North Beach last week. Photo by Jan Kacian, just before he put out the fire. the brush behind their campsite. Rangers found a fire smoldering Yes, fires are good for the forest environment, as in the green brush the next day after the campers left. our habitats use fires to clean out debris and keep the Some clueless visitors at North Beach somehow forests healthy. But with hundreds of homes started a fire in the brush near the beach, which a surrounding the park, we have safer ways to do that diver found early the next morning as he prepared to kind of work, without the heartache of devastated go diving. -

A Theory of Deception and Then of Common Law Categories

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2007 A Theory of Deception and then of Common Law Categories Saul Levmore Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Saul Levmore, "A Theory of Deception and then of Common Law Categories," 85 Texas Law Review 1359 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Texas Law Review Volume 85, Number 6, May 2007 Articles A Theory of Deception and then of Common Law Categories Saul Levmore* I. Introduction Deception is a regular feature of matters that give rise to legal conflict, and yet we do not think of cases with deception or fraud as a common element as doctrinally related. I will suggest here that they can, in fact, usefully be thought of as a group. From that observation there follows the more abstract question of why judges have not thought of these cases as related. The common denominator of "deception" has not often motivated them to decide cases in ways that take into account decisions rendered in other deception cases. My aim here is to explain this sort of narrow judicial focus, or brand of "minimalism" as I will sometimes call it, and to argue that the reason for this selective minimalism is an important and unrecognized part of the common law process.