Download the Country Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Development of the Communication Regulatory

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Adin Sadic March 2006 2 This thesis entitled HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 by ADIN SADIC has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the College of Communication by __________________________________________ Gregory Newton Associate Professor of Telecommunications __________________________________________ Gregory Shepherd Interim Dean, College of Communication 3 SADIC, ADIN. M.A. March 2006. Communication Studies History and Development of the Communication Regulatory Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1998 – 2005 (247 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gregory Newton During the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) over 250,000 people were killed, and countless others were injured and lost loved ones. Almost half of the B&H population was forced from their homes. The ethnic map of the country was changed drastically and overall damage was estimated at US $100 billion. Experts agree that misuse of the media was largely responsible for the events that triggered the war and kept it going despite all attempts at peace. This study examines and follows the efforts of the international community to regulate the broadcast media environment in postwar B&H. One of the greatest challenges for the international community in B&H was the elimination of hate language in the media. There was constant resistance from the local ethnocentric political parties in the establishment of the independent media regulatory body and implementation of new standards. -

Skopje, 2021 ANALYSIS: Media Freedom and Journalists’ Safety in RNM Through the Prism of Existing Legal Solutions – HOW to REACH BETTER SOLUTIONS? IMPRESUM

BALKAN CIVIL SOCIETY DEVELOPMENT NETWORK Skopje, 2021 ANALYSIS: Media freedom and journalists’ safety in RNM through the prism of existing legal solutions – HOW TO REACH BETTER SOLUTIONS? IMPRESUM Title Analysis: Media freedom and journalists’ safety in RNM through the prism of existing legal solutions – How to reach better solutions? Publisher Association of Journalists of Macedonia Project Promoting dialogue between journalists’ associations and Western Balkan parliaments for stronger civil society sector English translation Kristina Naceva Graphic design Grafotrejd doo Skopje Print Grafotrejd doo Skopje Circulation 25 Disclaimer This document is prepared within the Project “Protecting Civic Space – Regional Civil Society Development Hub” financed by Sida and implemented by BCSDN. The content of this document, and the information and views presented do not represent the official positions and opinions of Sida and BCSDN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this document lies entirely with the author(s). Skopje, 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction..................................................... 7 2. Criminal Code ................................................... 9 2.1. Ineffective legal solutions and institutional constraints.......10 3. Media regulation – freedom and independence of audiovisual media ...........................................17 3.1. Law on AVMS – state advertising threat to editorial policy.....17 3.2. Violated financial independence is violation of thefreedom of MRT ........................................................19 -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

A Medical Emergency Trafficking Pharmaceuticals from Tunisia to Libya

This project is funded by the European Union Issue 11 | March 2020 A medical emergency Trafficking pharmaceuticals from Tunisia to Libya Jihane Ben Yahia Summary Significant quantities of authentic medicines are being smuggled into Libya from neighbouring Tunisia by organised crime networks starting in Tunisia’s main medicine hubs: the Central Pharmacy, hospitals and private pharmacies. Their successful enterprise is due to weak links in the control and management of the supply chain of authorised medicines, a situation exacerbated since the 2011 revolution in Tunisia and aided by the current conflict in Libya. From April to Septemer 2018 ENACT’s Regional Organised Crime Observatory (ROCO) for North Africa investigated the problem and this paper explores its complexities and suggests some solutions. Key points • Structural deficiencies in the control of the medicine supply chain in Tunisia have allowed criminal organisations to exploit the system. • The demand in Libya has been met specifically by Tunisia, which produces large quantities of high-quality drugs and is home to well-established international pharmaceutical companies. • The violence resulting from the conflict in Libya has left thousands in need of constant medical care, creating a demand for smuggled medicines. • While medicines have always been smuggled between the two countries, the humanitarian situation in Libya has amplified the problem. • Links with various new armed groups, themselves in need of medicines, have shifted centuries of smuggling practices. RESEARCH PAPER Background representatives of civil society organisations (CSOs) and smugglers. Early in 2018 health professionals in Tunisia reported shortages of more than 220 medicines,1 a situation Research into any aspect of transnational organised confirmed by the Tunisia Central Pharmacy (PCT), the crime encounters limitations as the necessary information public body with a monopoly on the importation and is, by definition, hidden. -

A New Paradigm: Perspectives on the Changing Mediterranean

A New Paradigm: Perspectives on the Changing Mediterranean Edited by Sasha Toperich and Andy Mullins Center for Transatlantic Relations Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University 1 Sasha Toperich and Andy Mullins, A New Paradigm: Perspectives on the Changing Mediterranean Washington, DC: Center for Transatlantic Relations, 2014 © Center for Transatlantic Relations, 2014 Center for Transatlantic Relations The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies The Johns Hopkins University 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 525 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 663 – 5880 Fax: (202) 663 – 5879 Email: [email protected] http://transatlantic.sais-jhu.edu ISBN 13: 9780989029483 Cover illustration by Peggy Irvine 2 A New Paradigm: Perspectives on the Changing Mediterranean Sasha Toperich and Andy Mullins, Editors Acknowledgements Preface Daniel Hamilton Introduction Sasha Toperich and Andy Mullins Regional Integration and Cooperation in North Africa Tunisia’s Awakening Economy: A Trilateral Vision to Incentivize Reforms Ghazi Ben Ahmed Libya Deserves Better Ghazi Ben Ahmed and Amel Awni Dajani An Alternative for Improving Human Security in the Middle East and North Africa Aylin Ünver Noi North Africa Awakening: New Hopes for Faster Inclusive Growth Ghazi Ben Ahmed and Slim Othmani Post-Arab Spring Security Challenges and Responses Libya: The Major Security Concern in Africa? Olivier Guitta The Arab Spring and Egypt’s Open Season against Women Emily Dyer Comparative Transitions: The Arab Spring in Local -

Macedonian Radio Television in Need of New Professional Standards

Macedonian Radio Television in Need of New Professional Standards Macedonian Radio Television in Need of New Professional Standards Dragan Sekulovski Introduction The functions of public service broadcasting in the Republic of North Macedonia (RNM) are performed by the Macedonian Radio Television (MRT)1 as stipulated in the Law on Audio- and Audio-Visual Media Services (LAAVMS). The Republic of North Macedonia is the founder of the MRT pursuant to the same Law and it operates as a public enterprise in accordance with the provision and conditions stipulated by law and the relevant implementing bylaws. According to applicable legislation the MRT is a public broadcasting service that operates independently of any government body, other public legal entities or business undertakings and must pursue an impartial editorial and business policy. 7KH057KDVWKHWDVNRISURGXFLQJDQGEURDGFDVWLQJFRQWHQWLQWKHȴHOGVRI information, education, science, culture and art, documentary and feature programmes, and music and entertainment content in Macedonian and in the languages of other non-majority communities. The MRT is also required to produce content for people with disabilities and special needs (news and special programmes for viewers with impaired hearing). Through radio and TV satellite and/or via the internet, the MRT broadcasts 24-hour content that LVDYDLODEOHWRYLHZHUVDQGOLVWHQHUVLQ(XURSHDQGEH\RQG7KHDɝUPDWLRQ and nurturing of traditions, the spiritual and cultural heritage and values of all ethnic communities, as well as the preservation of the cultural and national identity are part of the essential mission of the MRT. The MRT is a highly atypical broadcasting service in Europe because its programmes are broadcast LQQLQHGLHUHQWODQJXDJHV7KXVLQDGGLWLRQWR0DFHGRQLDQWKH057SURGXFHV content in Albanian, Turkish, Serbian, Roma, Vlach and Bosnian. -

Download the Report

National Approaches to Extremism TUNISIA Tasnim Chirchi, Intissar Kherigi, Khaoula Ghribi The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, under Grant Agreement no. 870772 This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870772 Consortium Members CONNEKT COUNTRY REPORTS Published by the European Institute of the Mediterranean D3.2 COUNTRY REPORTS ON NATIONAL APPROACHES TO EXTREMISM Framing Violent Extremism in the MENA region and the Balkans TUNISIA Tasnim Chirchi, Director, Jasmine Foundation for Research and Communication Intissar Kherigi, Director of Programs, Jasmine Foundation for Research and Communication Khaoula Ghribi, Researcher, Jasmine Foundation for Research and Communication This publication is part of the WP3 of the project, lead by the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) Editors: Corinne Torrekens and Daphné de le Vingne Reviewers: Lurdes Vidal and Jordi Moreras Editorial team: Mariona Rico and Elvira García Layout: Núria Esparza December 2020 This publication reflects only the views of the author(s); the European Commission and Research Executive Agency are not responsible for any information it contains. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or the European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMed). Framing Violent Extremism in the MENA region and the Balkans Tunisia Overview1 COUNTRY PROFILE Government system During the period between Tunisia’s independence in 1956 and the 2011 Revolution, the Tunisian political system was a republican presidential system based on a single ruling party (the Neo-Destour Party, during Bourguiba’s period, and the Democratic and Constitutional Rally (RCD) party under Ben Ali’s era). -

Political Thought 57.Indb

POLITICAL THOUGHT YEAR 17, NO 57, JUNE, SKOPJE 2019 Publisher: Konrad Adenauer Foundati on, Republic of North Macedonia Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Skopje Founders: Dr. Gjorge Ivanov, Andreas Klein M.A. Politi čka misla - Editorial Board: Johannes D. Rey Konrad Adenauer Foundati on, Germany Nenad Marković Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Politi cal Science Department, Faculty of Law “Iusti nianus I”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Ivan Damjanovski Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Politi cal Science Department, Faculty of Law “Iusti nianus I”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Hans-Rimbert Hemmer Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Giessen, Germany Claire Gordon London School of Economy and Politi cal Science, England Robert Hislope Politi cal Science Department, Union College, USA Ana Matan-Todorcevska Faculty of Politi cal Science, Zagreb University, Croati a Predrag Cveti čanin University of Niš, Republic of Serbia Vladimir Misev OSCE Offi ce for Democrati c Insti tuti ons and Human Rights, Poland Sandra Koljačkova Konrad Adenauer Foundati on, Republic of North Macedonia Address: KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG ul. Risto Ravanovski 8 MK - 1000 Skopje Phone: 02 3217 075; Fax: 02 3217 076; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.kas.de INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY “SOCIETAS CIVILIS” SKOPJE Mitropolit Teodosij Gologanov 42A/3 MK - 1000 Skopje; Phone/ Fax: 02 30 94 760; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.idscs.org.mk E-mail: [email protected] Printi ng: Vincent grafi ka - Skopje Design & Technical preparati on: Pepi Damjanovski Translati on: Perica Sardzoski, Barbara Dragovikj Macedonian Language Editor: Elena Sazdovska The views expressed in the magazine are not views of Konrad Adenauer Foundati on and the Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis” Skopje. -

The Mirage of Regionalism in the Middle East and North Africa Post-2011

MENARA Working Papers No. 18, October 2018 THE MIRAGE OF REGIONALISM IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA POST-2011 Raffaella A. Del Sarto and Eduard Soler i Lecha This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement No 693244 Middle East and North Africa Regional Architecture: Mapping Geopolitical Shifts, Regional Order and Domestic Transformations WORKING PAPERS No. 18, October 2018 THE MIRAGE OF REGIONALISM IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA POST-2011 Raffaella A. Del Sarto and Eduard Soler i Lecha1 ABSTRACT Existing regional cooperation platforms in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are internally fragmented and largely ineffective. Focusing on the League of Arab States, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the Arab Maghreb Union, this paper discusses attempts to re- energize and instrumentalize existing regional organizations following the Arab uprisings. It shows that regional developments at the time provided significant opportunities for regional cooperative security mechanisms to emerge, resulting in an exceptional but brief period of activism by these organizations. As the mirage of regionalism quickly faded, intra-regional rivalries, in a period of pronounced uncertainty, led to the eventual failure to foster any significant regional cooperation. While internal divisions are currently threatening the very survival of the GCC, new and potentially short-lived forms of cooperation have been emerging, with bilateral alliances between like- minded regimes becoming prominent. MENA is an increasingly fragmented but simultaneously interconnected region, as exemplified by the mismatch between failed regionalism and a growing regionalization. Concurrently, the contours of MENA regional dynamics are becoming increasingly blurred as sub-regions are transformed into the borderlands of specific regional cores, with some players in the Gulf emerging as such cores. -

Association of Journalists of Macedonia PUBLIC POLICY DOCUMENT STATUS and NEED of CORRESPONDENTS in the REPUBLIC of NORTH MACEDONIA

Association of Journalists of Macedonia PUBLIC POLICY DOCUMENT STATUS AND NEED OF CORRESPONDENTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA Dragan Sekulovski, Project Director August 2019 This publication was prepared within the framework of the project “Secure Journalists for Credible Information in Macedonia” supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Skopje. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of AJM and the authors and in no way it reflects the position of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Skopje. Publisher: Association of Journalists of Macedonia Gradski Zid, blok 13 1000, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Phone: 00389 (02) 3298-139 e-mail: [email protected] I.I. ВОВЕДINTRODUCTION he media and journalism in the Republic of North Macedonia are facing numerous challenges. TThe current trend in the media field in the Republic of North Macedonia continues to show strong vulnerability. Over the past decade, the situation in journalism has been at a critical level in many respects and this has contributed to the deterioration of the situation of correspondents – journal- ists from the internal parts of the country. II. SITUATION ANALYSIS With the application of information technologies, it is expected that this situation will evolve towards new trends in the media, which will *develop with intensity*. This means that the digital environment will con- tribute towards changing the media format and the public habits for their application. It is important that this process does not disrupt the basic purpose of the media, to be public service informants and watchdogs of democracy in society - at central, but also at local level. -

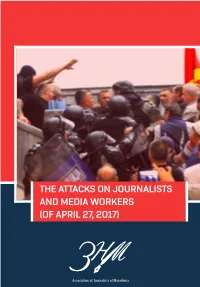

The Attacks on Journalists and Media Workers (Of April 27, 2017)

www.znm.org.mk THE ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS AND MEDIA WORKERS (OF APRIL 27, 2017) Association of Journalists of Macedonia THE ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS MEDIA WORKERS (OF APRIL 27, 2017) THE ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS AND AND MEDIA WORKERS (OF APRIL 27, 2017) Authors: Dushica Mrgja, journalist Enis Murtezi, journalist Hristina Belovska, journalist Edited by: Dragan Sekulovski and Deniz Sulejman Translation into English: Igor Markovski Photography: Media Information Agency - MIA December 2019, Skopje This publication was prepared in the framework of the project “Safe Journalists for Credible Information in Macedonia” supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Skopje. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of AJM and authors and can in no way reflect the position of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Skopje. Publisher: Association of Journalists of Macedonia (AJM) Gradski Zid, block 13, 1000 Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Dragan Sekulovski, Project Head Tel: 00389 (02) 3298-139 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS December 2019, two years and eight months after the THE ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS AND MEDIA WORKERS (OF APRIL 27, 2017) . 1 Bloody Thursday of April 27, 2017 3 Attack on the reporters in Parliament from the . 2 perspective of political actors 12 2.1. “We shared the same fate” 13 2.2. “No one was safe that day” 14 2.3. The parties on Bloody Thursday and the attack on journalists 15 2.4. Journalists sacrificed their lives to cover the bloody scenes 18 3. The dispute resolution for the attacked journalists on April 27 19 3.1.