Public Policies and Finance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Development of the Communication Regulatory

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Adin Sadic March 2006 2 This thesis entitled HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 by ADIN SADIC has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the College of Communication by __________________________________________ Gregory Newton Associate Professor of Telecommunications __________________________________________ Gregory Shepherd Interim Dean, College of Communication 3 SADIC, ADIN. M.A. March 2006. Communication Studies History and Development of the Communication Regulatory Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1998 – 2005 (247 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gregory Newton During the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) over 250,000 people were killed, and countless others were injured and lost loved ones. Almost half of the B&H population was forced from their homes. The ethnic map of the country was changed drastically and overall damage was estimated at US $100 billion. Experts agree that misuse of the media was largely responsible for the events that triggered the war and kept it going despite all attempts at peace. This study examines and follows the efforts of the international community to regulate the broadcast media environment in postwar B&H. One of the greatest challenges for the international community in B&H was the elimination of hate language in the media. There was constant resistance from the local ethnocentric political parties in the establishment of the independent media regulatory body and implementation of new standards. -

Carbon Finance Guide for Local Governments

The Community Development Carbon Fund (CDCF) provides carbon finance to projects in the poorer areas of the developing world. The Fund, a public/private initiative designed in cooperation with the International Emissions Trading Association and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, became operational in March 2003. The first tranche of the CDCF is capitalized at $128.6 million with nine governments and 16 corporations/organizations participating in it and is closed to further subscriptions. The CDCF supports projects that combine community development attributes with emission reductions to create “development plus carbon” credits, and will significantly improve the lives of the poor and their local environment. Carbon Finance Guide for Local Governments The World Bank Carbon Finance Unit’s (CFU) initiatives are part of the larger global effort to combat climate change, and go hand in hand with the World Bank and its Environment Department’s mission to reduce poverty and improve living standards in the developing world. The CFU uses money contributed by governments and companies in OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) Coordinated by countries to purchase project-based greenhouse gas emission reductions in developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Haddy J. Sey Task Team Leader, World Bank The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) is one of the world’s top policy research organisations focusing on sustainable development. With partners on five continents, IIED is helping to tackle 21st-century challenges ranging from climate change and cities to the pressures on Written by natural resources and the forces shaping global markets. -

Skopje, 2021 ANALYSIS: Media Freedom and Journalists’ Safety in RNM Through the Prism of Existing Legal Solutions – HOW to REACH BETTER SOLUTIONS? IMPRESUM

BALKAN CIVIL SOCIETY DEVELOPMENT NETWORK Skopje, 2021 ANALYSIS: Media freedom and journalists’ safety in RNM through the prism of existing legal solutions – HOW TO REACH BETTER SOLUTIONS? IMPRESUM Title Analysis: Media freedom and journalists’ safety in RNM through the prism of existing legal solutions – How to reach better solutions? Publisher Association of Journalists of Macedonia Project Promoting dialogue between journalists’ associations and Western Balkan parliaments for stronger civil society sector English translation Kristina Naceva Graphic design Grafotrejd doo Skopje Print Grafotrejd doo Skopje Circulation 25 Disclaimer This document is prepared within the Project “Protecting Civic Space – Regional Civil Society Development Hub” financed by Sida and implemented by BCSDN. The content of this document, and the information and views presented do not represent the official positions and opinions of Sida and BCSDN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this document lies entirely with the author(s). Skopje, 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction..................................................... 7 2. Criminal Code ................................................... 9 2.1. Ineffective legal solutions and institutional constraints.......10 3. Media regulation – freedom and independence of audiovisual media ...........................................17 3.1. Law on AVMS – state advertising threat to editorial policy.....17 3.2. Violated financial independence is violation of thefreedom of MRT ........................................................19 -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Moving to a Low-Carbon Economy: the Financial Impact of the Low- Carbon Transition

Moving to a Low-Carbon Economy: The Financial Impact of the Low- Carbon Transition Climate Policy Initiative David Nelson Morgan Hervé-Mignucci Andrew Goggins Sarah Jo Szambelan Julia Zuckerman October 2014 CPI Energy Transition Series October 2014 The Financial Impact of the Low-Carbon Transition Descriptors Sector Renewable Energy Finance Region Global, United States, European Union, China, India Keywords Stranded assets, low-carbon, finance, renewable energy Contact David Nelson, [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge input from expert reviewers, including Billy Pizer of Duke University, Karthik Ganesan of CEEW, Michael Schneider of Deutsche Bank, Nick Robins of UNEP, and Vikram Widge of the World Bank. The perspectives expressed in this paper are CPI’s own. We also thank our colleagues who provided analytical contributions, internal review, and publication support, including Ruby Barcklay, Jeff Deason, Amira Hankin, Federico Mazza, Elysha Rom-Povolo, Dan Storey, and Tim Varga. About CPI Climate Policy Initiative is a team of analysts and advisors that works to improve the most important energy and land use policies around the world, with a particular focus on finance. An independent organization supported in part by a grant from the Open Society Foundations, CPI works in places that provide the most potential for policy impact including Brazil, China, Europe, India, Indonesia, and the United States. Our work helps nations grow while addressing increasingly scarce resources and climate risk. This is a complex challenge in which policy plays a crucial role. About this project The reports were commissioned by the New Climate Economy project as part of the research conducted for the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. -

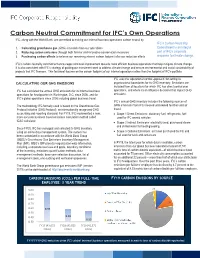

IFC Carbon Neutrality Committment Factsheet

Carbon Neutral Commitment for IFC’s Own Operations IFC, along with the World Bank, are committed to making our internal business operations carbon neutral by: IFC’s Carbon Neutrality 1. Calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from our operations Commitment is an integral 2. Reducing carbon emissions through both familiar and innovative conservation measures part of IFC's corporate 3. Purchasing carbon offsets to balance our remaining internal carbon footprint after our reduction efforts response to climate change. IFC’s carbon neutrality commitment encourages continual improvement towards more efficient business operations that help mitigate climate change. It is also consistent with IFC’s strategy of guiding our investment work to address climate change and ensure environmental and social sustainability of projects that IFC finances. This factsheet focuses on the carbon footprint of our internal operations rather than the footprint of IFC’s portfolio. IFC uses the ‘operational control approach’ for setting its CALCULATING OUR GHG EMISSIONS organizational boundaries for its GHG inventory. Emissions are included from all locations for which IFC has direct control over IFC has calculated the annual GHG emissions for its internal business operations, and where it can influence decisions that impact GHG operations for headquarters in Washington, D.C. since 2006, and for emissions. IFC’s global operations since 2008 including global business travel. IFC’s annual GHG inventory includes the following sources of The methodology IFC formally used is based on the Greenhouse Gas GHG emissions from IFC’s leased and owned facilities and air Protocol Initiative (GHG Protocol), an internationally recognized GHG travel: accounting and reporting standard. -

Macedonian Radio Television in Need of New Professional Standards

Macedonian Radio Television in Need of New Professional Standards Macedonian Radio Television in Need of New Professional Standards Dragan Sekulovski Introduction The functions of public service broadcasting in the Republic of North Macedonia (RNM) are performed by the Macedonian Radio Television (MRT)1 as stipulated in the Law on Audio- and Audio-Visual Media Services (LAAVMS). The Republic of North Macedonia is the founder of the MRT pursuant to the same Law and it operates as a public enterprise in accordance with the provision and conditions stipulated by law and the relevant implementing bylaws. According to applicable legislation the MRT is a public broadcasting service that operates independently of any government body, other public legal entities or business undertakings and must pursue an impartial editorial and business policy. 7KH057KDVWKHWDVNRISURGXFLQJDQGEURDGFDVWLQJFRQWHQWLQWKHȴHOGVRI information, education, science, culture and art, documentary and feature programmes, and music and entertainment content in Macedonian and in the languages of other non-majority communities. The MRT is also required to produce content for people with disabilities and special needs (news and special programmes for viewers with impaired hearing). Through radio and TV satellite and/or via the internet, the MRT broadcasts 24-hour content that LVDYDLODEOHWRYLHZHUVDQGOLVWHQHUVLQ(XURSHDQGEH\RQG7KHDɝUPDWLRQ and nurturing of traditions, the spiritual and cultural heritage and values of all ethnic communities, as well as the preservation of the cultural and national identity are part of the essential mission of the MRT. The MRT is a highly atypical broadcasting service in Europe because its programmes are broadcast LQQLQHGLHUHQWODQJXDJHV7KXVLQDGGLWLRQWR0DFHGRQLDQWKH057SURGXFHV content in Albanian, Turkish, Serbian, Roma, Vlach and Bosnian. -

The Financial Impact of the Low- Carbon Transition

Moving to a Low-Carbon Economy: The Financial Impact of the Low- Carbon Transition Climate Policy Initiative David Nelson Morgan Hervé-Mignucci Andrew Goggins Sarah Jo Szambelan Julia Zuckerman October 2014 CPI Energy Transition Series October 2014 The Financial Impact of the Low-Carbon Transition Descriptors Sector Renewable Energy Finance Region Global, United States, European Union, China, India Keywords Stranded assets, low-carbon, finance, renewable energy Contact David Nelson, [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge input from expert reviewers, including Billy Pizer of Duke University, Karthik Ganesan of CEEW, Michael Schneider of Deutsche Bank, Nick Robins of UNEP, and Vikram Widge of the World Bank. The perspectives expressed in this paper are CPI’s own. We also thank our colleagues who provided analytical contributions, internal review, and publication support, including Ruby Barcklay, Jeff Deason, Amira Hankin, Federico Mazza, Elysha Rom-Povolo, Dan Storey, and Tim Varga. About CPI Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) works to improve the most important energy and land use policies around the world, with a particular focus on finance. We support decision makers through in-depth analysis on what works and what does not. CPI works in places that provide the most potential for policy impact including Brazil, China, Europe, India, Indonesia, and the United States. Our work helps nations grow while addressing increasingly scarce resources and climate risk. This is a complex challenge in which policy plays a crucial role. About this project The reports were commissioned by the New Climate Economy project as part of the research conducted for the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. -

Political Thought 57.Indb

POLITICAL THOUGHT YEAR 17, NO 57, JUNE, SKOPJE 2019 Publisher: Konrad Adenauer Foundati on, Republic of North Macedonia Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Skopje Founders: Dr. Gjorge Ivanov, Andreas Klein M.A. Politi čka misla - Editorial Board: Johannes D. Rey Konrad Adenauer Foundati on, Germany Nenad Marković Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Politi cal Science Department, Faculty of Law “Iusti nianus I”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Ivan Damjanovski Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Politi cal Science Department, Faculty of Law “Iusti nianus I”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Hans-Rimbert Hemmer Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Giessen, Germany Claire Gordon London School of Economy and Politi cal Science, England Robert Hislope Politi cal Science Department, Union College, USA Ana Matan-Todorcevska Faculty of Politi cal Science, Zagreb University, Croati a Predrag Cveti čanin University of Niš, Republic of Serbia Vladimir Misev OSCE Offi ce for Democrati c Insti tuti ons and Human Rights, Poland Sandra Koljačkova Konrad Adenauer Foundati on, Republic of North Macedonia Address: KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG ul. Risto Ravanovski 8 MK - 1000 Skopje Phone: 02 3217 075; Fax: 02 3217 076; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.kas.de INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY “SOCIETAS CIVILIS” SKOPJE Mitropolit Teodosij Gologanov 42A/3 MK - 1000 Skopje; Phone/ Fax: 02 30 94 760; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.idscs.org.mk E-mail: [email protected] Printi ng: Vincent grafi ka - Skopje Design & Technical preparati on: Pepi Damjanovski Translati on: Perica Sardzoski, Barbara Dragovikj Macedonian Language Editor: Elena Sazdovska The views expressed in the magazine are not views of Konrad Adenauer Foundati on and the Insti tute for Democracy “Societas Civilis” Skopje. -

Carbon Finance & Cattle Externalities in the Brazilian Amazon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-9-2010 Carbon Finance & Cattle Externalities in the Brazilian Amazon: Pricing Reforestation in terms of Restoration Ecology Christian T. Hofer University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Hofer, Christian T., "Carbon Finance & Cattle Externalities in the Brazilian Amazon: Pricing Reforestation in terms of Restoration Ecology" (2010). Honors Scholar Theses. 166. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/166 Carbon Finance & Cattle Externalities in the Brazilian Amazon: Pricing Reforestation in terms of Restoration Ecology Undergraduate Thesis presented to the University of Connecticut Honors Program April 30, 2010 Christian Hofer School of Business, B.S. Finance Candidate Faculty Advisor: Robert J. Martel, Ph.D. Department of Economics Abstract This paper evaluates land-use conflict between cattle pasture and tropical rainforest in the Brazilian Amazon and attempts to reconcile negative production externalities within the framework of carbon finance. Specifically, it analyzes the price per metric ton of CO 2e that would make reforestation projects, in terms of restoration ecology, a viable land-use alternative. Regional information on opportunity, implementation, and transaction costs is used to develop a partial equilibrium cost-benefit analysis, in which carbon sequestration is the only benefit. Financing is employed through Kyoto’s Clean Development Mechanism and long-term certified emission reductions (lCERs) are the carbon financial instrument modeled. -

Finance Guide for Policy-Makers: Renewable Energy, Green Infrastructure

FINANCE GUIDE FOR POLICY-MAKERS: RENEWABLE ENERGY, GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE 2016 UPDATE Kirsty Hamilton, Low Carbon Finance Group, Chatham House and Ethan Zindler, Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) have written and produced this updated guide. Grateful acknowledgment for their insight and expertise is made to the following individuals, including practitioners from the Low Carbon Finance Group, BNEF and others, whose financial experience has been invaluable to understanding and translating finance practices and concepts, and identifying key elements of the investment environment relevant to policy-makers: Will Blyth, Andrew Buglass, Germana Canzi, Mike Clark, Catherine Craig, Anna Czajowska, Charlie Donovan, Felix Fallasch, Steven Fawkes, Antony Froggatt, Nick Gardiner, Mark Knox, Silvie Kreibiehl; Aleksi Lumijarvi, Seb Meaney, Ben Moxham, Liam O’Keeffe, Brian Potowski, Julian Richardson, Allison Robertshaw, Joe Salvatore, Martin Schoenberg, Virginia Sonntag O’Brien, Peter Sweatman, Ian Temperton, Mike Wilkins, Henning Wuester, Eugene Zhuchenko. First edition written and produced by Kirsty Hamilton and Sophie Justice, 2009. Kirsty Hamilton has more than 25 years’ experience in climate and energy policy. She initiated work with renewable energy finance practitioners in 2004, as an Associate Fellow at Chatham House, examining ‘investment grade’ policy, and then led the policy work of the Low Carbon Finance Group from 2010 to 2015. [email protected] Sophie Justice, PhD is a financial consultant with extensive international banking experience. August 2016 Bloomberg New Energy Finance Bloomberg New Energy Finance provides unique analysis, tools and data for decision-makers driving change in the energy system. BNEF helps clients stay on top of developments across the energy spectrum with a comprehensive web-based platform. -

Association of Journalists of Macedonia PUBLIC POLICY DOCUMENT STATUS and NEED of CORRESPONDENTS in the REPUBLIC of NORTH MACEDONIA

Association of Journalists of Macedonia PUBLIC POLICY DOCUMENT STATUS AND NEED OF CORRESPONDENTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA Dragan Sekulovski, Project Director August 2019 This publication was prepared within the framework of the project “Secure Journalists for Credible Information in Macedonia” supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Skopje. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of AJM and the authors and in no way it reflects the position of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Skopje. Publisher: Association of Journalists of Macedonia Gradski Zid, blok 13 1000, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Phone: 00389 (02) 3298-139 e-mail: [email protected] I.I. ВОВЕДINTRODUCTION he media and journalism in the Republic of North Macedonia are facing numerous challenges. TThe current trend in the media field in the Republic of North Macedonia continues to show strong vulnerability. Over the past decade, the situation in journalism has been at a critical level in many respects and this has contributed to the deterioration of the situation of correspondents – journal- ists from the internal parts of the country. II. SITUATION ANALYSIS With the application of information technologies, it is expected that this situation will evolve towards new trends in the media, which will *develop with intensity*. This means that the digital environment will con- tribute towards changing the media format and the public habits for their application. It is important that this process does not disrupt the basic purpose of the media, to be public service informants and watchdogs of democracy in society - at central, but also at local level.