De)Constructing Genre and Gender in Westworld (Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan, HBO, 2016-

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

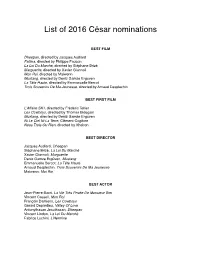

List of Cesar Nominations 2016

List of 2016 César nominations! ! ! ! BEST! FILM! Dheepan, directed by Jacques Audiard! Fatima, directed by Philippe Faucon! La Loi Du Marché, directed by Stéphane Brizé! Marguerite, directed by Xavier Giannoli! Mon Roi, directed by Maiwenn! Mustang, directed by Deniz Gamze Erguven! La Tête Haute, directed by Emmanuelle Bercot! !Trois Souvenirs De Ma Jeunesse, directed by Arnaud Desplechin! ! ! BEST FIRST FILM! L’Affaire SK1, directed by Frédéric Tellier! Les Cowboys, directed by Thomas Bidegain! Mustang, directed by Deniz Gamze Erguven! Ni Le Ciel Ni La Terre, Clément Cogitore! !Nous Trois Ou Rien, directed by Kheiron! ! ! BEST DIRECTOR! Jacques Audiard, Dheepan! Stéphane Brizé, La Loi Du Marché! Xavier Giannoli, Marguerite! Deniz Gamze Ergüven, Mustang! Emmanuelle Bercot, La Tête Haute! Arnaud Desplechin, Trois Souvenirs De Ma Jeunesse! !Maïwenn, Moi Roi! ! ! BEST ACTOR! Jean-Pierre Bacri, La Vie Très Privée De Monsieur Sim! Vincent Cassell, Mon Roi! François Damiens, Les Cowboys! Gérard Depardieu, Valley Of Love! Antonythasan Jesuthasan, Dheepan! Vincent Lindon, La Loi Du Marché! !Fabrice Luchini, L’Hermine! ! ! ! BEST ACTRESS! Loubna Abidar, Much Loved! Emmanuelle Bercot, Mon Roi! Cécile de France, La Belle Saison! Catherine Deneuve, La Tête Haute! Catherine Frot, Marguerite! Isabelle Huppert, Valley Of Love! !Soria Zeroual, Fatima! ! BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR! Michel Fau, Marguerite! Louis Garrel, Mon Roi! Benoit Magimel, La Tête Haute! André Marcon, Marguerite! !Vincent Rottiers, Dheepan! ! ! BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS! Sara Forestier, -

Webb Management Services

building creativity Webb Management Services ✲ Webb Management Services, Inc. is North America’s leading provider of arts and cultural project planning services ✲ We work for governments, schools, developers, and arts organizations on facility feasibility, business planning, strategic planning, and cultural planning ✲ Our practice was founded in 1997, and we just started our 348th assignment ✲ Previous work in the region includes projects in Chandler and Mesa, as well as a Cultural Facilities Master Plan for the Scottsdale Cultural Council Webb Management Services Inc. Page 1 building creativity Additional team members Elizabeth Healy, Healy Entertainment Elizabeth recently re-launched Healy Entertainment, a development and production company. One of her first clients is The Recording Academy (GRAMMY Awards Organization), which follows on the heels of her eight- year term as senior executive director of The Recording Academy New York Chapter. Her work there included developing and producing over 400 special programs and events for the company. Elizabeth's past experience also includes working at significant performing arts organizations such as Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York City Ballet, Saratoga Performing Arts Center, and Finger Lakes Performing Arts Center, in addition to several major record companies, and with world renowned artists. Christine Ewing, Ewing Consulting Christine has a proven track record of more than 25 years producing successful financial development programs for a broad range of vital nonprofit -

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Novita' – Giugno

NOVITA’ – GIUGNO DVD: - A CIAMBRA di Jonas Carpignano, 2017 - BETTER CALL SAUL. TERZA STAGIONE di Vince Gilligan e Peter Gould, Serie TV, 2017 - BLACK SAILS. TERZA STAGIONE di Robert Levine e Jonathan E. Steinberg, Serie TV, 2016 - CARNERA. THE WALKING MOUNTAIN di Renzo Martinelli, 2008 - CATTIVISSIMO ME 3 di Kyle Balda e Pierre Coffin, Animazione, 2017 - CHE GUEVARA. IL MITO RIVOLUZIONARIO, Documentario, 2007 - IL COLORE NASCOSTO DELLE COSE di Silvio Soldini, 2017 - I DELITTI DEL BARLUME. QUARTA STAGIONE di Marco Malvaldi, Serie TV, 2017 - DELITTO SOTTO IL SOLE di Guy Hamilton, 1982 - DIARIO DI UNA SCHIAPPA. PORTATEMI A CASA di David Bowers, 2017 - DINOSAUR ISLAND. VIAGGIO NELL'ISOLA DEI DINOSAURI di Matt Drummond, 2014 - DRAGON BALL. SERIE TV COMPLETA. VOL. 1 di Minoru Okazaki, Serie TV d’Animazione, 1986 - DUNKIRK di Christopher Nolan, 2017 - EASY. UN VIAGGIO FACILE FACILE di Andrea Magnani, 2017 - LE FANTASTICHE AVVENTURE DI PIPPI CALZELUNGHE. VOL. 7, Serie TV, 1969 - FULLMETAL ALCHEMIST. THE MOVIE. IL CONQUISTATORE DI SHAMBALLA di Seiji Mizushima, Animazione, 2005 - IL FUTURO È DONNA di Marco Ferreri, 1984 - GREY'S ANATOMY. UNDICESIMA STAGIONE di Shonda Rhimes, Serie TV, 2014-2015 - GREY’S ANATOMY. DODICESIMA STAGIONE di Shonda Rhimes, Serie TV, 2015-2016 - GREY’S ANATOMY. TREDICESIMA STAGIONE di Shonda Rhimes, Serie TV, 2016-2017 - IO SONO STEVE MCQUEEN di Jeff Renfroe, Documentario, 2014 - LIFE ANIMATED di Roger Ross Williams, Documentario, 2016 - MAGIC MIKE XXL di Gregory Jacobs, -

Struction of the Feminine/Masculine Dichotomy in Westworld

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 2 (2020) Skin-Deep Gender: Posthumanity and the De(con)struction of the Feminine/Masculine Dichotomy in Westworld Amaya Fernández Menicucci ABSTRACT: This article addresses the ways in which gender configurations are used as representations of the process of self-construction of both human and non-human characters in Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy’s series Westworld, produced by HBO and first launched in 2016. In particular, I explore the extent to which the process of genderization is deconstructed when human and non-human identities merge into a posthuman reality that is both material and virtual. In Westworld, both cyborg and human characters understand gender as embodiment, enactment, repetition, and codified communication. Yet, both sets of characters eventually face a process of disembodiment when their bodies are digitalized, which challenges the very nature of identity in general and gender identity in particular. Placing this digitalization of human identity against Donna Haraway’s cyborg theory and Judith Butler’s citational approach to gender identification, a question emerges, which neither Posthumanity Studies nor Gender Studies can ignore: can gender identities survive a process of disembodiment? Such, indeed, is the scenario portrayed in Westworld: a world in which bodies do not matter and gender is only skin-deep. KEYWORDS: Westworld; gender; posthumanity; embodiment; cyborg The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world. The cyborg is also the awful apocalyptic telos of the ‘West’s’ escalating dominations . (Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto 8) Revolution in a Post-Gender, Post-Race, Post-Class, Post-Western, Posthuman World The diegetic reality of the HBO series Westworld (2016-2018) opens up the possibility of a posthuman existence via the synthesis of individual human identities and personalities into algorithms and a post-corporeal digital life. -

Casual and Hardcore Players in HBO's Westworld (2016): the Immoral and Violent Player

Casual and Hardcore Players in HBO’s Westworld (2016): The Immoral and Violent Player MA Thesis Ellen Menger – 5689295 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. René Glas Second reader: Dr. Jasper van Vught Utrecht University MA New Media & Digital Culture MCMV10009 - THE-Masterthesis/ MA NMDC May 8, 2017 Abstract This thesis approaches the HBO series Westworld (2016) through the lens of game studies and interprets the series as a commentary on the stereotype of casual and hardcore players and immoral violence in video games. By performing a textual analysis, this thesis explores how Westworld as a series makes use of the casual and hardcore player stereotype, looking at the way the series explores the construction of player categories and how it ties these to the dialogue about violence and immoral behaviour in video games. Keywords: Westworld, games, player types, Western, casual gamer, hardcore gamer, violence, ethics, morals SPOILER WARNING This thesis reveals certain plot twists that may spoil part of the storyline of the first season of HBO’s Westworld. If you have not watched the series, read at your own risk. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2. Theoretical framework ....................................................................................................... 7 2.1. (Im)moral Behaviour in Game Worlds ....................................................................... 7 2.2. The Player as a Moral -

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

Call for Abstracts Westworld and Philosophy Richard Greene & Josh

Call for Abstracts Westworld and Philosophy Richard Greene & Josh Heter, Editors Abstracts are sought for a collection of philosophical essays related to the HBO television series Westworld (we also welcome essays on the 1973 movie of the same name on which it is based, the 1976 sequel to that movie, Futureworld, and the subsequent 1980 television series, Beyond West World). This volume will be published by Open Court Publishing (the publisher of The Simpsons and Philosophy, The Matrix and Philosophy, Dexter and Philosophy, The Walking Dead and Philosophy, Boardwalk Empire and Philosophy, and The Princess Bride and Philosophy, etc.) as part of their successful Popular Culture and Philosophy series. We are seeking abstracts, but anyone who has already written an unpublished paper on this topic may submit it in its entirety. Potential contributors may want to examine other volumes in the Open Court series. Contributors are welcome to submit abstracts on any topic of philosophical interest that pertains to Westworld. The editors are especially interested in receiving submissions that engage philosophical issues/topics/concepts in Westworld in creative and non-standard ways. Please feel free to forward this to anyone writing within a philosophic discipline who might be interested in contributing. Contributor Guidelines: 1. Abstract of paper (100–750 words) 2. Resume/CV for each author/coauthor of the paper 3. Initial submission should be made by email (we prefer e-mail with MS Word attachment) 4. Deadlines: Abstracts due February 1, 2018 First drafts due April 1, 2018 Final drafts due June 1, 2018 (we are looking to complete the entire ms by June 15, 2018, so early submissions are encouraged and welcomed!) Email: [email protected] . -

Comprehensive Anti-Racism Resources

COMPREHENSIVE ANTI-RACISM RESOURCES Compiled by UNY Conference Commission on Religion and Race Members and the General Commission on Religion & Race Online Resources Study Links – GCORR Lenten Study Series: Roll Down Justice: Six-session study guides and videos www.gcorr.org/series/lenten-series-roll-down-justice/ Racial Justice Conversation Guide www.gcorr.org/racial-justice-conversation-guide/ Is Reverse Racism Really a Thing? Study guide & video www.gcorr.org/is-reverse-racism-really-a-thing/ Wait…That’s Privilege? Article with Privilege Quiz www.gcorr.org/wait-thats-privilege/ Study Links – Other Sources United Methodist Women’s Lenten Study on Racial Justice www.unitedmethodistwomen.org/lent www.youtube.com/watch?v=XITxqC0Sze4 Eye on the Prize – a PSB documentary series (14 episodes) www.youtube.com/watch?v=NpY2NVcO17U UMW Tools for Leaders: Resources for Racial Justice https://s3.amazonaws.com/umw/pdfs/racialjustice2012.pdf 2 Websites National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): https://www.naacp.org Southern Poverty Law Center: https://www.splcenter.org General Commission on Religion and Race (GCORR): http://www.gcorr.org/ Black Lives Matter: https://blacklivesmatter.com Local groups involved in anti-racism action in your area Podcasts www.insocialwork.org/list_categories.asp Videos Getting Called Out – How to Apologize: www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8xJXLYL.8pU&feature=youtube).UnderstandingMy Privilege The Danger of a Single Story www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story/transcr ipt?languafe=en PBS, "Race: The Power of an Illusion." Three one-hour videos with discussion questions, 2003. https://www.pbs.org/race/000_General/000_00-Home.htm Crossing the Color Line | Brennon Thompson | TEDxSUNYGeneseo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3UQUT4LMhAw "Free Indeed," a video drama about racism and white privilege, available at UNY Resource Center. -

Pieces of a Woman

PIECES OF A WOMAN Directed by Kornél Mundruczó Starring Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf, Molly Parker, Sarah Snook, Iliza Shlesinger, Benny Safdie, Jimmie Falls, Ellen Burstyn **WORLD PREMIERE – In Competition – Venice Film Festival 2020** **OFFICIAL SELECTION – Gala Presentations – Toronto International Film Festival 2020** Press Contacts: US: Julie Chappell | [email protected] International: Claudia Tomassini | [email protected] Sales Contact: Linda Jin | [email protected] 1 SHORT SYNOPSIS When an unfathomable tragedy befalls a young mother (Vanessa Kirby), she begins a year-long odyssey of mourning that touches her husband (Shia LaBeouf), her mother (Ellen Burstyn), and her midwife (Molly Parker). Director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014) and partner/screenwriter Kata Wéber craft a deeply personal meditation and ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. SYNOPSIS Martha and Sean Carson (Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf) are a Boston couple on the verge of parenthood whose lives change irrevocably during a home birth at the hands of a flustered midwife (Molly Parker), who faces charges of criminal negligence. Thus begins a year-long odyssey for Martha, who must navigate her grief while working through fractious relationships with her husband and her domineering mother (Ellen Burstyn), along with the publicly vilified midwife whom she must face in court. From director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014), with artistic support from executive producer Martin Scorsese, and written by Kata Wéber, Mundruczó’s partner, comes a deeply personal, searing domestic aria in exquisite shades of grey and an ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. -

Le Programme October – November 2017 02 Contents/Highlights

Le Programme October – November 2017 02 Contents/Highlights Ciné Lumière 3–17 Performances & Talks 18–20 Projet Lumière(s) 20 61st BFI London Film Festival Tribute to Jeanne Moreau 25th French Film Festival South Ken Kids Festival 22 5 – 15 Oct 19 Oct – 17 Dec 2 – 9 Nov p.6 pp.16-17 pp.9-13 Kids & Families 23 We Support 24 We Recommend 25 French Courses 27 South Ken Kids Festival Impro! Suzy Storck La Médiathèque / Culturethèque 28 13 – 19 Nov 18 Nov 26 Oct – 18 Nov p.22 p.18 Gate Theatre p.24 General Information 29 front cover image: Redoubtable by Michel Hazanavicius Programme design by dothtm Ciné Lumière New Releases Le Correspondant In Between On Body and Soul FRA/BEL | 2016 | 85 mins | dir. Jean-Michel Ben Soussan, Bar Bahar Teströl és lélekröl with Charles Berling, Sylvie Testud, Jimmy Labeeu, Sophie PSE/ISR/FRA | 2016 | 102 mins | dir. Maysaloun Hamoud, with HUN | 2017 | 116 mins | dir. Ildikó Enyedi, with Géza Mousel | cert. tbc | in French with EN subs Mouna Hawa, Sana Jammelieh, Shaden Kanboura | cert. 15 Morcsányi, Alexandra Borbély, Zoltán Schneider | cert. 18 in Hebrew & Arabic with EN subs in Hungarian with EN subs Malo and Stéphane are two students who are kind of losers and have just started high school. Their genious Winner of the Young Talents Award in the Women in Marking a singular return for Hungarian writer-director plan to become popular: to host a German exchange Motion selection in Cannes this year, In Between follows Ildikó Enyedi after an 18-year gap, On Body and Soul tells student with a lot of style, preferably a hot girl. -

2018 – Volume 6, Number

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 & 3 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Bump in the Night” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of Pixabay/Kellepics EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH PAUL BOOTH Minnesota State University, Moorhead DePaul University GARY BURNS ANNE M. CANAVAN Northern Illinois University Salt Lake Community College BRIAN COGAN ASHLEY M. DONNELLY Molloy College Ball State University LEIGH H. EDWARDS KATIE FREDICKS Florida State University Rutgers University ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO KATHLEEN A. KENNEDY Maryville University of St. Louis Missouri State University SARAH MCFARLAND TAYLOR KIT MEDJESKY Northwestern University University of Findlay CARLOS D. MORRISON SALVADOR MURGUIA Alabama State University Akita International