Trinidad and Tobago National Protected Areas Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

By Philip R. Woodside U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 8L This

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE PETROLEUM GEOLOGY OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By Philip R. Woodside U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 8l This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature* Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsment by the USGS. 1981 CONTENTS Page For ewo r d •————————•———-————————————————•————————•—•————•—— Abstract —• Introduction ——————————————————————————————————————————— 1 Structural Geology ————•—-———————•———•—•—————-———•—•——•—— 4 Introduction -——————————————————————————————————————— 4 Structural Areas of Trinidad ——————————————————————————— 5 The Northern Range ——————————•—————————————————————— 5 The Northern (Caroni) Basin —————————————————————————— 6 The Central Range ————————————————————————————————— 6 The Southern Basin (including Naparima Thrust Belt) ———————— 6 Los Bajos fault ———————————————————————————————— 7 The Southern Range ————————————————————————————————— 9 Shale Diapirs ———————————————————————————————————— 10 Stratigraphy ——————————————————————————————————————————— 11 Northern Range and Northern Basin ——————————————————————— 11 Central Range —————————————————————————————————————— 12 Southern Basin and Southern Range —————-————————————————— 14 Suimnary ————————————————————————————————————————————— 18 Oil and Gas Occurrence ———•——————————•——-——————•————-—•—•— 19 Introduction ————•—•————————————————————————-—— 19 Hydrocarbon Considerations -

Health and Climate Change: Country Profile 2020

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO HEALTH & CLIMATE CHANGE COUNTRY PROFILE 2020 Small Island Developing States Initiative CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 KEY RECOMMENDATIONS 3 BACKGROUND 4 CLIMATE HAZARDS RELEVANT FOR HEALTH 7 HEALTH IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE 9 HEALTH VULNERABILITY AND ADAPTIVE CAPACITY 11 HEALTH SECTOR RESPONSE: MEASURING PROGRESS Acknowledgements This document was developed in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Planning and Development, who together with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) gratefully acknowledge the technical contributions of Mr Arnold Ramkaran, Dr Roshan Parasram, Mr Lawrence Jaisingh and Mr Kishan Kumarsingh. Financial support for this project was provided by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). ii Health and Climate Change Country Profile “Many of the public health gains we have made in recent decades are at risk due to the direct and indirect impacts of climate variability and climate change.” EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Despite producing very little greenhouse gas policies, building resilience must happen in emissions that cause climate change, people parallel with the reduction of carbon emissions living in small island developing States (SIDS) by countries around the world. are on the frontline of climate change impacts. The WHO Special Initiative on Climate Change These countries face a range of acute to long- and Health in SIDS aims to provide national term risks, including extreme weather events health authorities in SIDS with the political, such as floods, droughts and cyclones, increased technical and financial support required to better average temperatures and rising sea levels. -

Education in Trinidad and Tobago

An Overview of The Educational System of Trinidad & Tobago American & Caribbean Law Initiative Fall 2008 Introduction to Trinidad and Tobago Located 7 mile off the coast of Venezuela The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago has a population of approximately 1.3 million inhabitants Majority of the population is located in Trinidad with about 50,000 inhabitants on the smaller island of Tobago Ruled by the British, Trinidad and Tobago gained independence in 1962 and declared itself a republic in 1976 The economy is largely based on the country’s abundance of natural resources, particularly Oil and Gas. Introduction to Trinidad and Tobago The country has a stable government and considers itself to be a leading political and economic power in the Caribbean. The total GDP in 2005 was approximately 14 million USD Literacy rate is 98.6- highest in the Caribbean The official language is English with French, Chinese, Spanish and the Caribbean Hindustani, a dialect of Hindi also spoken Map of Trinidad and Tobago Education System Based on British Model Education is free and compulsory for children ages 5 to 13 years of age Education System divided into 3 phases: Primary Education Secondary Education Higher Education Higher Education Higher Education is post-secondary study leading to diploma, certificates and degrees Two major higher education institutions: University of West Indies National Institute for Higher Education Primary Education Primary consists of 2 preparatory ("infant") grades and 5 "standard" grades Includes children -

Caribbean Sea Volume Ii

PUB. 148 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ CARIBBEAN SEA VOLUME II ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Bethesda, Maryland © COPYRIGHT 2004 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2004 EIGHTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 Preface 0.0 Pub. 148, Sailing Directions, (Enroute) Caribbean Sea, for every influence tending to cause deviation from such track, Volume II, Eighth Edition, 2004, is issued for use in and navigate so that the designated course is continuously conjunction with Pub. 140, Sailing Directions (Planning being made good. Guide) North Atlantic Ocean, North Sea, Baltic Sea, and the 0.0 Currents.—Current directions are the true directions toward Mediterranean Sea. Companion volumes are Pubs. 141, 142, which currents set. 143, 145, and 147. 0.0 Dangers.—As a rule outer dangers are fully described, but 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 27 November 2004, inner dangers which are well-charted are, for the most part, including Notice to Mariners No. 48 of 2004. omitted. Numerous offshore dangers, grouped together, are mentioned only in general terms. Dangers adjacent to a coastal Explanatory Remarks passage or fairway are described. 0.0 Distances.—Distances are expressed in nautical miles of 1 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- minute of latitude. Distances of less than 1 mile are expressed Intelligence Agency (NGA), under the authority of Department in meters, or tenths of miles. -

Life C Ycle Summar Y

Economic Impact of IAS in the Caribbean Case Studies Life C ycle Summar y 4.5-5.5 mm Adult snail lives up to 9 yrs E ggs in bat ches 100-400/yr CABI 8-12 days Grows to 20 cm long Grows over the yrs Economic Impact of IAS in the Caribbean Case Studies CABI Gordon Street, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies December 2014 CABI. 2014 Economic Impact of IAS in The Caribbean: Case Studies Available in PDF format at www.ciasnet.org CABI encourages the fair use of this document. Proper citation is requested. Editor: Naitram Ramnanan Layout: Karibgraphics ISBN 978-976-8255-07-5 Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago 2014 All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors and editors. Acknowledgements CAB International (CABI) has more than a century of global experience in managing pest and diseases in agriculture and the environment with a focus on integrated pest management and biological control. In this context, it’s Centre for the Caribbean and Central America (CCA) began more than a decade ago, its efforts at managing invasive species in the Caribbean. This began with a study for the Nature Conservancy (TNC) to determine the ‘Invasive Species Threats in the Caribbean Region’. That effort identified a large number Invasive Species in the insular Caribbean and made some recommendations for managing this issue, regionally. CABI then partnered with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), The Department of Marine Resources in the Bahamas; the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources in the Dominican Republic; the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA) in Jamaica; the Forestry Department, Ministry of Sustainable Development, Energy, Science and Technology in Saint Lucia; and the Ministry of Food Production in Trinidad and Tobago. -

Microtityus Rickyi (Dwarf Scorpion)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Diversity Microtityus rickyi (Dwarf Scorpion) Order: Scorpiones (Scorpions) Class: Arachnida (Spiders, Scorpions and Mites) Phylum: Arthropoda (Arthropods) Fig. 1. Dwarf scorpion, Microtityus rickyi. [www.ntnu.no/ub/scorpion-files/m_rickyi2.jpg, downloaded 23 October 2016] TRAITS. Microtityus rickyi are the smallest scorpions of the Western Hemisphere with an average size of 19mm. A light yellow pigmentation with black to light brown spots is found throughout the carapace (anterior plate that covers the head and thorax) and opisthosoma (segmented mid-body and tail). Its stinger is dark brown. The almost triangular carapace with a distinctly notched margin is characteristic of Microtiyus rickyi (Fig. 1). Sexual dimorphism is exhibited in regards to their size; the largest females are 18.6mm and males 16.6mm (Kjellesvig- Waering, 1966) DISTRIBUTION. Microtityus rickyi are endemic to Trinidad and Tobago, found nowhere else, and rather rare, comprising less than 1% of the scorpion population sampled (Kjellesvig- UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Diversity Waering, 1966). Microtityus rickyi can be found at Lady Chancellor Hill, Mt. St. Benedict, Chacachacare Island, Gaspar Grande Island (Fig. 2), and Speyside Tobago (Prendini, 2001). HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. Microtityus rickyi are predominantly found hanging motionless on the underside of rocks within forests, on exposed soil banks or leaf litter though some have been found near the coast and on hills at heights of 200m. They can also be considered as semi- arboreal as some have been found a few metres up tree trunks (Prendini, 2001). FOOD AND FEEDING. -

Trinidad and Tobago: Venezuelan Refugees at Risk

First UA: 126/20 AMR 49/2953/2020 Trinidad and Tobago Date: 13 August 2020 URGENT ACTION VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AT RISK At least 165 Venezuelans have been deported by Trinidad and Tobago in recent weeks. Pushing a xenophobic narrative targeting Venezuelans and associating them with COVID-19, the government announced it will deport Venezuelans who have “entered illegally” and those with legal residency found to be helping them. This fuels a climate of fear which risks pushing people underground and away from health services. We are calling on Trinidad and Tobago to refrain from deporting people in search of protection and to work with partners to find human rights-based solutions for them. TAKE ACTION: WRITE AN APPEAL IN YOUR OWN WORDS OR USE THIS MODEL LETTER The Honourable Dr Keith Rowley Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago 13-15 St Clair Avenue Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago Phone number: +1 (868) 622-1625 Emails: [email protected]; [email protected]; Dear Prime Minister, I write to you with deep concern over reports that at least 165 Venezuelans were deported from Trinidad and Tobago to their country in recent weeks. Trinidad and Tobago must guarantee and protect the rights of refugees and people seeking international protection. Millions of Venezuelans are fleeing an unprecedented human rights crisis in their country. They need a life jacket, not to be sent back to a country where they may face torture or other grave human rights violations. Instead, Venezuelan refugees and those who support them are targeted by xenophobic narratives and accusations of increasing the risks of COVID-19 for Trinidad and Tobago people, justifying procedures of deportation without properly assess the danger that those returned may face in Venezuela. -

The Journey That Is Chacachacare - Part 1/3 a Personal Account by Hans E.A.Boos

Quarterly Bulletin of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists’ Club January - March 2010 Issue No: 1/2010 The journey that is Chacachacare - part 1/3 A personal account by Hans E.A.Boos Several years ago I was asked, by Yasmin Comeau of the National Herbarium, U.W.I St. Augustine to write a short history titled “Human occupation and impact on the island of Chacachacare‖ ( which constitutes the main body of the account below), which was to be a part of a larger work on the vegetation of the island of Chacachacare. But, in that I do not know if it was ever published in any part or its entirety, I thought I would share it, and some more recent additions and observations, with the members of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists‘ Club, a club of which I have been proud to be a member since the middle of 1960. Chacachacare holds a special place in my interest, which interest will A part of the Leper colony be elaborated on below, and which was again sparked during a recent Photo Hans E. A. Boos excursion of the Club to this island on Sunday March 28th 2010. (Continued on page 3) Page 2 THE FIELD NATURALIST Issue No. 1/2010 Inside This Issue Quarterly Bulletin of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists’ Club 1 Cover January - March 2010 The Journey that is Chacachacare - A personal account by Hans E. A. Boos Editor Shane T. Ballah 7 Club Monthly Field Trip Report Editorial Committee La Table 31- 01 - 2010 Palaash Narase, Reginald Potter - Reginald Potter Contributing writers Christopher K. -

The Paradox of Children's Rights in Trinidad: Translating International Law Into Domestic Reality

THE PARADOX OF CHILDREN'S RIGHTS IN TRINIDAD: TRANSLATING INTERNATIONAL LAW INTO DOMESTIC REALITY by Charrise L. Clarke B.A. (Honours), York University 2005 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the School of Criminology © Charrise L. Clarke 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Charrise L. Clarke Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Paradox of Children's Rights in Trinidad: Translating International Law into Domestic Reality Examining Committee: Chair: Bryan Kinney Assistant Professor David MacAlister Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor Sheri Fabian Supervisor Lecturer Fiona Kelly External Examiner Assistant Professor University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: ii SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

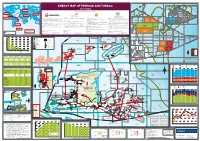

View the Energy Map of Trinidad and Tobago, 2017 Edition

Trinidad and Tobago LNG export destinations 2015 (million m3 of LNG) Trinidad and Tobago deepwater area for development 60°W 59°W 58°W Trinidad and Tobago territorial waters ENERGY MAP OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 1000 2000 m m 2017 edition GRENADA BARBADOS Trinidad and Tobago 2000m LNG to Europe A tlantic Ocean 2.91 million m3 LNG A TLANTIC Caribbean 2000m 20 Produced by Petroleum Economist, in association with 00 O CEAN EUROPE Sea m Trinidad and Tobago 2000m LNG to North America NORTH AMERICA Trinidad and Tobago 5.69 million m3 LNG LNG to Asia 3 GO TTDAA 30 TTDAA 31 TTDAA 32 BA 1.02 million m LNG TO Trinidad and Tobago OPEN OPEN OPEN 12°N LNG to MENA 3 1.90 million m LNG ASIA Trinidad and Tobago CARIBBEAN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 2000m LNG to Caribbean Atlantic LNG Company profile Company Profile Company profile Company Profile 3 Established by the Government of Trinidad and Tobago in August 1975, The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) is an BHP Billiton is a leading global resources company with a Petroleum Business that includes exploration, development, production and marketing Shell has been in Trinidad and Tobago for over 100 years and has played a major role in the development of its oil and gas industry. Petroleum Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (Petrotrin) is an integrated Oil and Gas Company engaged in the full range of petroleum 3.84 million m LNG internationally investment-graded company that is strategically positioned in the midstream of the natural gas value chain.