Engineering-Geological Features Supporting a Seismic-Driven Multi-Hazard Scenario in the Lake Campotosto Area (L’Aquila, Italy)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Fabric Anisotropy on the Dynamic Mechanical Behavior Of

EFFECT OF FABRIC ANISOTROPY ON THE DYNAMIC MECHANICAL BEHAVIOR OF GRANULAR MATERIALS by Bo Li Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Prof. Xiangwu Zeng Department of Civil Engineering Case Western Reserve University January, 2011 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Bo Li Candidate for Ph. D. degree*. (signed) Xiangwu Zeng Chair of Commitee Adel Saada Wojbor A. Woyczynski Xiong Yu (date) 11/15/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein Table of Contents Table of Contents I List of Tables IV List of Figures VI Acknowledgement XI Abstract XII Notation XIV Chapter 1 Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 Effect of Anisotropy on Granular Materials ........................................................................... 1 1.2 Research Objectives ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Outline of the Dissertation ...................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Review of the Effect of Fabric Anisotropy on Clay ............................................................... 3 1.4.1 Experimental Study on Effect of Fabric Anisotropy on Clay ......................................... 3 1.4.2 Analytical Method on Effect of Fabric Anisotropy -

Confidential Manuscript Submitted to Engineering Geology

Confidential manuscript submitted to Engineering Geology 1 Landslide monitoring using seismic refraction tomography – The 2 importance of incorporating topographic variations 3 J S Whiteley1,2, J E Chambers1, S Uhlemann1,3, J Boyd1,4, M O Cimpoiasu1,5, J L 4 Holmes1,6, C M Inauen1, A Watlet1, L R Hawley-Sibbett1,5, C Sujitapan2, R T Swift1,7 5 and J M Kendall2 6 1 British Geological Survey, Environmental Science Centre, Nicker Hill, Keyworth, 7 Nottingham, NG12 5GG, United Kingdom. 2 School of Earth Sciences, University 8 of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, United 9 Kingdom. 3 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), Earth and 10 Environmental Sciences Area, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, United 11 States of America. 4 Lancaster Environment Center (LEC), Lancaster University, 12 Lancaster, LA1 4YQ, United Kingdom 5 Division of Agriculture and Environmental 13 Science, School of Bioscience, University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington, 14 Leicestershire, LE12 5RD, United Kingdom 6 Queen’s University Belfast, School of 15 Natural and Built Environment, Stranmillis Road, Belfast, BT9 5AG, United 16 Kingdom 7 University of Liege, Applied Geophysics, Department ArGEnCo, 17 Engineering Faculty, B52, 4000 Liege, Belgium 18 19 Corresponding author: Jim Whiteley ([email protected]) 20 21 Copyright British Geological Survey © UKRI 2020/ University of Bristol 2020 22 1 Confidential manuscript submitted to Engineering Geology 23 Abstract 24 Seismic refraction tomography provides images of the elastic properties of 25 subsurface materials in landslide settings. Seismic velocities are sensitive to 26 changes in moisture content, which is a triggering factor in the initiation of many 27 landslides. -

On the Wave Bottom Shear Stress in Shallow Depths: the Role of Wave Period and Bed Roughness

water Article On the Wave Bottom Shear Stress in Shallow Depths: The Role of Wave Period and Bed Roughness Sara Pascolo *, Marco Petti and Silvia Bosa Dipartimento Politecnico di Ingegneria e Architettura, University of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (S.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0432-558-713 Received: 6 September 2018; Accepted: 25 September 2018; Published: 28 September 2018 Abstract: Lagoons and coastal semi-enclosed basins morphologically evolve depending on local waves, currents, and tidal conditions. In very shallow water depths, typical of tidal flats and mudflats, the bed shear stress due to the wind waves is a key factor governing sediment resuspension. A current line of research focuses on the distribution of wave shear stress with depth, this being a very important aspect related to the dynamic equilibrium of transitional areas. In this work a relevant contribution to this study is provided, by means of the comparison between experimental growth curves which predict the finite depth wave characteristics and the numerical results obtained by means a spectral model. In particular, the dominant role of the bottom friction dissipation is underlined, especially in the presence of irregular and heterogeneous sea beds. The effects of this energy loss on the wave field is investigated, highlighting that both the variability of the wave period and the relative bottom roughness can change the bed shear stress trend substantially. Keywords: finite depth wind waves; bottom friction dissipation; friction factor; tidal flats; bottom shear stress 1. Introduction The morphological evolution of estuarine and coastal lagoon environments is a widely discussed topic in literature, because of its complexity and the great variability of morphological patterns. -

Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential of Soil by Down Borehole Method

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conferences on Recent Advances 2010 - Fifth International Conference on Recent in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Soil Dynamics Engineering and Soil Dynamics 26 May 2010, 4:45 pm - 6:45 pm Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential of Soil by Down Borehole Method Sumit Ghose Bengal Engineering and Science University, India Ambarish Ghosh Bengal Engineering and Science University, India Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icrageesd Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Ghose, Sumit and Ghosh, Ambarish, "Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential of Soil by Down Borehole Method" (2010). International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics. 15. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icrageesd/05icrageesd/session01/15 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF LIQUEFACTION -

Defining P-Wave and S-Wave Stratal Surfaces with Nine-Component Vsps

INTERPRETER’S CORNER Coordinated by Rebecca B. Latimer Defining P-wave and S-wave stratal surfaces with nine-component VSPs BOB A. HARDAGE, MICHAEL DEANGELO, and PAUL MURRAY, Bureau of Economic Geology, Austin, Texas, U.S. Nine-component vertical seismic profile (9C VSP) data were acquired across a three-state area (Texas, Kansas, Colorado) to evaluate the relative merits of imaging Morrow and post-Morrow stratigraphy with compressional (P-wave) seismic data and shear (S-wave) seismic data. 9C VSP data generated using three orthogonal vector sources were used in this study rather than 3C data generated by only a ver- tical-displacement source because the important SH shear mode would not have been available if only the latter had been acquired. The popular SV converted mode (or C wave) utilized in 3C seismic technology is created by P-to-SV mode conversions at nonvertical angles of incidence at subsurface interfaces rather than propagating directly from an SV source as in 9C data acquisition. In contrast, 9C acquisition generates a P-wave mode and both fundamental S-wave modes (SH and SV) directly at the source station and allows these three basic compo- nents of the elastic seismic wavefield to be isolated from each other for imaging purposes. The purpose of these field tests was to compare SH, SV, and P reflectivity at targeted inter- faces. Because C waves were not an imaging objective, we used zero-offset acquisition geometry, which caused C-wave reflectivity to be quite small. We consider zero offset a source- to-receiver offset that is less than one-tenth of the depth to the shallowest receiver station. -

Seismic Site Classifications for the St. Louis Urban Area

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Engineering Faculty Research & Creative Works Engineering 01 Jun 2012 Seismic Site Classifications for the St. Louis Urban Area Jaewon Chung J. David Rogers Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/geosci_geo_peteng_facwork Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation J. Chung and J. D. Rogers, "Seismic Site Classifications for the St. Louis Urban Area," Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, vol. 102, no. 3, pp. 980-990, Seismological Society of America, Jun 2012. The definitive version is available at https://doi.org/10.1785/0120110275 This Article - Journal is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Engineering Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 102, No. 3, pp. 980–990, June 2012, doi: 10.1785/0120110275 Seismic Site Classifications for the St. Louis Urban Area by Jae-won Chung and J. David Rogers Abstract Regional National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program (NEHRP) soil class maps have become important input parameters for seismic site character- ization and hazard studies. The broad range of shallow shear-wave velocity (VS30, the average shear-wave velocity in the upper 30 m) measurements in the St. -

This Regulation Shall Be Binding in Its Entirety and Directly Applicable in All Member States

12. 8 . 91 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 223/ 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 2396/91 of 29 July 1991 fixing for the 1990/91 marketing year the yields of olives and olive oil THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas the measures provided for in this Regulation are in accordance with the opinion of the Management Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Committee for Oils and Fats, Economic Community, Having regard to Council Regulation No 136/66/EEC of 22 September 1966 on the establishment of a common HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : organization of the market in oils and fats ('), as last amended by Regulation (EEC) No 1720/91 (2) ; Article 1 Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 2261 /84 of 17 July 1984 laying down general rules on the granting 1 . For the 1990/91 marketing year, yields of olives and of aid for the production of olive oil and of aid to olive oil olive oil and the relevant production zones shall be as producer organizations (3), as last amended by Regulation specified in Annex I hereto . (EEC) No 3500/90 (4), and in particular Article 19 thereof, 2. The production zones are defined in Annex II . Whereas Article 18 of Regulation (EEC) No 2261 /84 provides that yields of olives and olive oil should be fixed for each homogeneous production zone on the basis of Article 2 information supplied by the producer Member States ; This Regulation shall enter into force on the third day Whereas, in view of the information received, it is appro following its publication in the Official Journal of the priate to fix these yields as specified in Annex I hereto ; European Communities. -

Elenchi Idonei Alla Rete Di “Agricoltori Custodi” Divisi Per Tipologia

PROGRAMMA L.E.A.D.E.R. + Piano di Sviluppo Locale “ARCA Abruzzo” Approvato con Determinazione Dirigenziale n. DH/21/03 del 24 aprile 2003 INIZIATIVA “CERERE” a regia GAL in Convenzione del GRUPPO DI AZIONE LOCALE G.A.L. “Consorzio ARCA Abruzzo” Soc. Coop. a r.l. con l’Ente Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga P.I.C. LEADER PLUS G.A.L. ARCA Abruzzo Finanziata con risorse FEOGA – LEADER + P.S.L. DEL GAL ARCA ABRUZZO e cofinanziata con risorse dell’ENTE PARCO NAZIONALE DEL GRAN SASSO E MONTI DELLA LAGA ASSE II COOPERAZIONE INTERTERRITORIALE “VALORIZZAZIONE DELLA CULTURA LOCALE: LA FLORA" INIZIATIVA “CERERE” ASSE 2: SOSTEGNO ALLA COOPERAZIONE TRA TERRITORI RURALI Misura 2.1: COOPERAZIONE INTERTERRITORIALE Azione 2.1.1.: REALIZZAZIONE DI SERVIZI COMUNI Iniziativa n. 6: “CERERE” Recupero, conservazione e valorizzazione delle antiche varietà colturali territoriali (frutta – cereali - leguminose e orticole) ELENCHI IDONEI ALLA RETE DI “AGRICOLTORI CUSTODI” DIVISI PER TIPOLOGIA RELATIVO ALL’AVVISO PUBBLICO PER DICHIARAZIONE DI INTERESSE ALLA PARTECIPAZIONE ALL’INIZIATIVA “CERERE” A REGIA GAL IN CONVENZIONE CON L’ENTE PARCO NAZIONALE DEL GRAN SASSO E MONTI DELLA LAGA nell’ambito del PROGRAMMA del GAL ARCA Abruzzo Soc. Coop. a r. l. volto a realizzare UNA RETE DI AGRICOLTORI CUSTODI DI VARIETA’ A RISCHIO ESTINZIONE nell’ambito dell’iniziativa “CERERE: RECUPERO, CONSERVAZIONE E VALORIZZAZIONE DELLE ANTICHE VARIETA’ COLTURALI TERRITORIALI, ORTICOLE, CEREALICOLE, LEGUMINOSE, FRUTTICOLE” ELENCO IDONEI ALLA RETE DI AGRICOLTORI CUSTODI COME TIPOLOGIA A (Agricoltori che coltivano una o più varietà locali a rischio di estinzione, ne forniscono una quota per gli agricoltori aderenti all’iniziativa e sono interessati a coltivare altra/e varietà nei propri campi) N NOMINATIVO UBICAZIONE TERRENI 1 Antonacci Mario Calascio, Castel del Monte 2 Anzuini Rosella Montereale- Ville di Fano 3 Az Agricola Coop Ofena, Capestrano, Castelvecchio Calvisio, Carapelle Collerotondo Calvisio, Calascio. -

Shear Wave Velocity and Its Effect on Seismic Design Forces and Liquefaction Assessment

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conference on Case Histories in (2004) - Fifth International Conference on Case Geotechnical Engineering Histories in Geotechnical Engineering 17 Apr 2004, 10:30am - 12:30pm Shear Wave Velocity and Its Effect on Seismic Design Forces and Liquefaction Assessment Thomas G. Thomann URS Corporation, New York, New York Khaled Chowdhury URS Corporation, New York, New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Thomann, Thomas G. and Chowdhury, Khaled, "Shear Wave Velocity and Its Effect on Seismic Design Forces and Liquefaction Assessment" (2004). International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. 2. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/5icchge/session03/2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHEAR WAVE VELOCITY AND ITS EFFECT ON SEISMIC DESIGN FORCES AND LIQUEFACTION ASSESSMENT Thomas G. Thomann Khaled Chowdhury URS Corporation URS Corporation New York, NY (USA) New York, NY (USA) ABSTRACT The shear wave velocity of soil and rock is one of the key components in establishing the design response spectra, and therefore the seismic design forces, for a building, bridge, or other structure. -

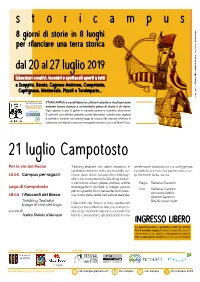

S T O R I C a M P

storicampus 8 giorni di storie in 8 luoghi Andrea Aste per rilanciare una terra storica / Illustrazione: / Illustrazione: dal 20 al 27 luglio 2019 laboratori creativi, incontri e spettacoli aperti a tutti a Scoppito, Barete, Cagnano Amiterno, Campotosto, ADV - Gabriella Monaco Monaco Capitignano, Montereale, Pizzoli e Tornimparte... Copy e grafca: PROGETTO OFFICINA STORICAMPUS è condividere la cultura in piazze e vicoli per dare DELLE STORIE 2019 insieme nuovo slancio a un territorio pieno di storia e di storie. Ogni giorno e per 8 giorni si cambia paese e scenario attraverso 8 comuni con attività gratuite come laboratori creativi per ragazzi e bambini, incontri con personaggi di spicco del mondo artistico e letterario, spettacoli e percorsi enogastronomici a cura di Slow Food. 21 luglio Campotosto Per le vie del Paese Trekking teatrale con attori, musicisti e dimensione fantastica in cui la leggenda spettatori immersi nella scenografa na- incontra la scienza, e la poesia nasce da- 10:00 Campus per ragazzi turale, dove storie fantastiche e mitologi- gli elementi della natura. che si intersecano con la vita degli abitan- ti del bosco: alberi, pietre, animali, anche Regia Stefania Evandro Lago di Campotosto microrganismi invisibili o troppo piccoli Con Stefania Evandro per lo sguardo di un passante sono mes- Armando Rotilio 18:00 I Racconti del Bosco si a fuoco dalla lente dell’azione teatrale. Alberto Santucci Trekking Teatrale Rita Scognamiglio I Racconti del Bosco è uno spettacolo lungo le rive del lago nato per raccontare la vita e la comples- a cura di sità degli elementi naturali e del sistema Teatro Stabile d’Abruzzo bosco e trasportare gli spettatori in una INGRESSO LIBERO La partecipazione è gratuita a tutti gli eventi Per il campus ragazzi: inviare domanda d’iscri- zione entro il 14 luglio a [email protected] Per il laboratorio bimbi non occorre prenotarsi CAPOFILA PATROCINI PARTNER Comune di SCOPPITO L’Aquila PER INFORMAZIONI E/O PRENOTAZIONI: [email protected] Storicampus storicampus Storicampus 2019. -

Europe's Greenest Region Gran Sasso E Monti Della Laga National Park Majella National Park Abruzzo, Lazio E Molise Na

en_ambiente&natura:Layout 1 3-09-2008 12:33 Pagina 1 Abruzzo: Europe’s 2 greenest region Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga 6 National Park 12 Majella National Park Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise 20 National Park Sirente-Velino 26 Regional Park Regional Reserves and 30 Oases Abruzzo Promozione Turismo - Corso V. Emanuele II, 301 - 65122 Pescara - Email [email protected] en_ambiente&natura:Layout 1 3-09-2008 12:33 Pagina 2 ABRUZZO In Abruzzo nature is a protected resource. With a third of its territory set aside as Park, the region not only holds a cultural and civil record for protection of the environment, but also stands as the biggest nature area in Europe: the real green heart of the Mediterranean. Abruzzo Promozione Turismo - Corso V. Emanuele II, 301 - 65122 Pescara - Email [email protected] en_ambiente&natura:Layout 1 3-09-2008 12:33 Pagina 3 ABRUZZO ITALY 3 Europe’s greenest region In Abruzzo, a third of the territory is set aside in protected areas: three National Parks, a Regional Park and more than 30 Nature Reserves. A visionary and tough decision by those who have made the environment their resource and will project Abruzzo into a major and leading role in “green tourism”. Overall most of this legacy – but not all – is to be found in the mountains, where the landscapes and ecosystems change according to altitude, shifting from typically Mediterranean milieus to outright alpine scenarios, with mugo pine groves and high-altitude steppe. Of all the Apennine regions, Abruzzo is distinctive for its prevalently mountainous nature, -

Genio Civile Dell'aquila

GENIO CIVILE DELL’AQUILA Divisione territoriale dei Comuni L’Ufficio Sismica L’Aquila è competente in materia sismica per i seguenti Comuni Acciano Castel del Monte Ocre Sant’Eusanio Forconese Barete Castelvecchio Calvisio Ofena Santo Stefano di Sessanio Barisciano Fagnano Alto Pizzoli Scoppito Cagnano Amiterno Fontecchio Poggio Picenze Tione degli Abruzzi Campotosto Fossa Prata d’Ansidonia Tornimparte Capestrano L’Aquila Rocca di Cambio Villa Santa Lucia Capitignano Lucoli Rocca di Mezzo Villa Sant’Angelo Caporciano Montereale San Demetrio ne’ Vestini Carapelle Calvisio Navelli San Pio delle Camere L’Ufficio Tecnico e Sismica Avezzano è competente in materia sismica e quale Autorità Idraulica per i seguenti Comuni Aielli Cerchio Massa d’Albe Rocca di Botte Avezzano Civita d’Antino Morino San Benedetto dei Marsi Balsorano Civitella Roveto Opi San Vincenzo Valle Roveto Bisegna Cocullo Oricola Sante Marie Canistro Collarmele Ortona dei Marsi Scurcola Marsicana Capistrello Collelongo Ortucchio Tagliacozzo Cappadocia Gioia dei Marsi Ovindoli Trasacco Carsoli Lecce dei Marsi Pereto Villavallelonga Castellafiume Luco dei Marsi Pescasseroli Celano Magliano dei Marsi Pescina L’Ufficio Tecnico e Sismica L’Aquila-Sulmona è competente in materia sismica per i seguenti Comuni Alfedena Castel di Sangro Pacentro Roccaraso Anversa degli Abruzzi Castelvecchio Subequo Pescocostanzo Scanno Ateleta Civitella Alfedena Pettorano sul Gizio Scontrone Barrea Collepietro Pratola Peligna Secinaro Bugnara Corfinio Prezza Sulmona Campo di Giove Gagliano Aterno Raiano