Malaysia Is Not a “Garbage Dump”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LSS Bukit Selambau Dilancar

Headline LSS Bukit Selambau dilancar MediaTitle Sinar Harian Date 01 Apr 2019 Language Malay Circulation 140,000 Readership 420,000 Section Selangor & KL Page No 37 ArticleSize 438 cm² Journalist SITI ZUBAIDAH PR Value RM 22,414 LSS Bukit Selambau dilancar Bawa manfaat bandar Sungai Petani itu. “Kita baru sahaja selesai info kepada menyempurnakan pro- penduduk, jadi gram terbesar dan berpres- Projek LLS di Bukit tij Pameran Aeroangkasa Selambau itu dijangka mercu tanda dan Maritim Antarabangsa mula beroperasi pada Langkawi 2019 (LIMA’19) hujung tahun 2020 yang berjalan lancar, anta- SITI ZUBAIDAH ZAKARAYA ra lain, hasil sokongan dan kerjasama TNB dengan ngan tarikh sasaran opera- SUNGAI PETANI menyiapkan sistem auto- si komersial pada 31 masi sepenuhnya peman- Disember 2020. tauan bekalan elektrik di “TNB yakin ini meru- rojek Solar Berskala Pulau Langkawi. pakan lokasi tepat berikut- P Besar (LSS) Tenaga “Saya difahamkan an Kedah antara negeri Nasional Berhad pemasangan sistem ini yang banyak menerima (TNB) bernilai RM180 juta membolehkan TNB cahaya matahari selepas bakal memanfaatkan pen- memantau dengan lebih Perlis berbanding negeri duduk Bukit Selambau, rapi lagi bekalan elektrik di Mukhriz menurunkan tandatangan sebagai gimik pelancaran Majlis Pecah Tanah LSS di Pekan Bukit lain di semenanjung,” ka- sekaligus membangunkan seluruh Pulau Langkawi Selambau, semalam. tanya. kawasan pinggir bandar dan bertindak pantas Beliau percaya, projek berkenaan. apabila ada gangguan dan bertuah kerana bakal dide- naga suria ini juga amat tama TNB dianugerahkan berkenaan sedikit sebanyak Menteri Besar Kedah, sebagainya, dan tempoh dahkan dengan perkem- sesuai di Kedah, kerana kita LSS oleh Suruhanjaya Te- memberi kesan limpahan Datuk Seri Mukhriz Ma- masa pemulihan dapat bangan teknologi masa antara negeri yang mene- naga adalah melalui proses kepada rakyat menerusi hathir berkata, projek yang dipendekkan. -

Inside This Issue

Ingenious NEWSLETTER INSIDE THIS ISSUE PG. 2 ENGINEERING, SCIENCE & ESTIC 2019 TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL PG. 3 MOU SIGNING CONFERENCE 2019 (ESTIC'19) PG. 4 14 & 15 OCTOBER 2019 MAHSA University’s Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology and MAHSA IET On DRAINAGE GATES PROJECT Campus have successfully organised its second “Engineering, Science & Technology International Conference 2019 (ESTIC’19)” on the 14th and 15th October 2019. EXCHANGE PROGRAM-JAPAN October 2019 PG. 6,7,8 Volume 1 Issue 3 FEIT,MAHSA University STUDENT ACTIVITIES, Kajang Rocks Level 9, Empathy Building, Bandar Saujana Putra, visit & TNB ILSAS 42610 Jenjarom, Selangor. Malaysia ENGINEERING, SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 2019 (ESTIC'19) 14 & 15 OCTOBER 2019 This conference is a platform to share innovative ideas, latest technological information, research findings and strategic solutions. The inaugural ceremony of this international conference was initiated with an opening speech by YB Tuan Haji Mohd Anuar Bin Mohd Tahir, Malaysia’s Deputy Minister of Works. Seven distinguished speakers from various renowned universities, professional bodies and relevant industries were invited for the keynote sessions. The eminent speakers were Dr. Audrey Yong (MAHSA University), IR Dr. Chuah Joon Huang (IET Malaysia Honorary Treasurer) , Dr. Nagaraja Suryadera (MAHSA University), Prof Dr. Mohammad Iftikhar Hanif , Ir Dr Lee Yun Fook (Sepakat Setia Perunding Sdn Bhd), IR Ellias Saidin (Consultant Engineering Firm), Prof. Ir Dr Wong Hin Yong (Multimedia University). Twenty international companies from the industrial sector and three professional bodies participated as exhibitors. They are Technological Association Malaysia (TAM), the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) Malaysia and the Institution of Engineers, Malaysia (IEM). -

SITUASI SEMASA LAPORAN MINGGUAN DEMAM DENGGI NEGERI SELANGOR Bagi Minggu Epidemiologi 35/2021 (Tarikh 29.08.21 - 04.09.21)

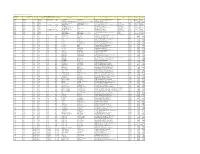

SITUASI SEMASA LAPORAN MINGGUAN DEMAM DENGGI NEGERI SELANGOR Bagi Minggu Epidemiologi 35/2021 (Tarikh 29.08.21 - 04.09.21) 1. Analisa bilangan kes berdasarkan daerah Pada minggu epidemiologi (ME) 35 iaitu bagi tempoh 29 Ogos hingga 4 September 2021, sejumlah 217 kes demam denggi telah dilaporkan di Negeri Selangor, iaitu penurunan sebanyak 18.4% berbanding 266 kes pada minggu sebelumnya. Sejumlah 10,797 kes demam denggi dilaporkan sehingga ME 35 yang berakhir pada 4 September 2021 iaitu penurunan sebanyak 70.6% ( 25,915 kes) berbanding minggu yang sama tahun 2020 (36,712 kes). Tiada kes kematian dilaporkan dalam tempoh ini. Kumulatif kes kematian sehingga ME 35 adalah dua kes menunjukkan penurunan 94.1 %, berbanding 34 kes kematian pada tempoh yang sama tahun lepas. Jadual 1: Perbandingan bilangan kes demam denggi mengikut daerah berdasarkan ME dan tahun sebelumnya KES KUMULATIF KES SEHINGGA DAERAH ME ME % Peningkatan/ ME ME % Peningkatan/ 34/2021 35/2021 Penurunan 35/2020 35/2021 Penurunan PETALING 88 82 -6.8% 12,942 3,419 -73.6% HULU LANGAT 74 72 -2.7% 7,352 3,044 -58.6% GOMBAK 63 29 -54.0% 5,279 1,986 -62.4% KLANG 25 24 -4.0% 6,303 1,534 -75.7% SEPANG 5 4 -20.0% 2,085 277 -86.7% HULU SELANGOR 6 1 -83.3% 1,220 123 -89.9% KUALA SELANGOR 4 2 -50.0% 721 205 -71.6% KUALA LANGAT 1 3 200.0% 699 202 -71.1% SABAK BERNAM 0 0 111 7 -93.7% SELANGOR 266 217 -18.4% 36,712 10,797 -70.6% ME 34/2021 = (22.08.2021 - 28.08.2021) ME 35/2021 = (29.08.2021 - 04.09.2021) Laporan Mingguan Demam Denggi Negeri Selangor...(MS 1/4) SITUASI SEMASA LAPORAN MINGGUAN DEMAM DENGGI NEGERI SELANGOR Bagi Minggu Epidemiologi 35/2021 (Tarikh 29.08.21 - 04.09.21) 2. -

30 Ogos 2021 (Isnin)

30 OGOS 2021 (ISNIN) MESYUARAT PERTAMA PENGGAL KEEMPAT DEWAN NEGERI SELANGOR YANG KEEMPAT BELAS TAHUN 2021 SHAH ALAM, 30 OGOS 2021 (ISNIN) Mesyuarat dimulakan pada jam 10.00 pagi YANG HADIR Y.B. Tuan Ng Suee Lim (Sekinchan) (Tuan Speaker) Y.A.B. Dato’ Seri Amirudin bin Shari (Sungai Tua) (Dato’ Menteri Besar Selangor) Y.B. Dato’ Teng Chang Khim, D.P.M.S. (Bandar Baru Klang) Y.B. Tuan Ganabatirau A/L Veraman (Kota Kemuning) Y.B. Puan Rodziah binti Ismail (Batu Tiga) Y.B. Tuan Ir. Izham bin Hashim (Pandan Indah) Y.B. Tuan Ng Sze Han (Kinrara) Y.B. Puan Dr. Siti Mariah binti Mahmud (Seri Serdang) Y.B. Tuan Hee Loy Sian (Kajang) 30 OGOS 2021 (ISNIN) Y.B. Tuan Mohd Khairuddin bin Othman (Paya Jaras) Y.B. Tuan Borhan bin Aman Shah, P.J.K. (Tanjong Sepat) Y.B. Tuan Mohd Zawawi bin Ahmad Mughni (Sungai Kandis) Y.B. Tuan Lau Weng San (Banting) Y.B. Tuan Haji Saari bin Sungib (Hulu Kelang) Y.B. Tuan Ean Yong Hian Wah (Seri Kembangan) Y.B. Puan Elizabeth Wong Keat Ping (Bukit Lanjan) Y.B. Puan Lee Kee Hiong (Kuala Kubu Baharu) Y.B. Tuan Dr. Idris bin Ahmad (Ijok) Y.B. Tuan Hasnul bin Baharuddin, P.P.T. (Morib) (Timbalan Speaker) Y.B. Tuan Rajiv A/L Rishyakaran (Bukit Gasing) Y.B. Tuan Ronnie Liu Tian Khiew (Sungai Pelek) Y.B. Puan Rozana binti Zainal Abidin (Permatang) Y.B. Puan Juwairiya binti Zulkifli (Bukit Melawati) Y.B. Tuan Ahmad Mustain bin Othman (Sabak) Y.B. Tuan Mohd Sany bin Hamzan (Taman Templer) Y.B. -

Development of an Erosion Model for Langat River Basin, Malaysia, Adapting GIS and RS in RUSLE

Applied Water Science (2020) 10:165 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-01185-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Development of an erosion model for Langat River Basin, Malaysia, adapting GIS and RS in RUSLE Md. Rabiul Islam1 · Wan Zurina Wan Jaafar2 · Lai Sai Hin2 · Normaniza Osman3 · Md. Razaul Karim2 Received: 4 April 2018 / Accepted: 30 March 2020 / Published online: 16 June 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract This study is aimed to predict potential soil erosion in the Langat River Basin, Malaysia by integrating Remote Sensing (RS) and Geographical Information System (GIS) with the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) model. In RUSLE model, parameters such as rainfall erosivity factor (R), soil erodibility factor (K), slope length and steepness factor (LS), vegetation cover and management factor (C) and support practice factor (P) are determined based on the input data followed by the spatial analysis process in the GIS platform. Rainfall data from 2008-2015 are collected from the 29 rain gauge stations located within the study area. From the analysis, the magnitude of RUSLE model obtained corresponding to the parameter R, K, LS, C and P factors is varied between 800 to 3000 MJ mm ha − 1 h− 1 yr− 1, 0.035–0.5 Mg h MJ− 1 mm− 1, 0–73.00, 0.075–0.77 and 0.2–1.00, respectively. Findings of this study indicates that based on the calculated RUSLE parameter values, about 95% of the Langat River Basin area have been classifed as a very low to a low erosion vulnerability. Findings of this study would greatly benefts a decision maker in proposing a suitable soil management and conservation practices for the river basin. -

Selangorkini Jun 4 2012

Penggerak Kemajuan Saksama PERCUMASelangor 15 - 22 Jun 2012, 25 Rejab - 2 Syaaban1433 Kini Notis 5A: Penerima Jangan rasuah jika OKU gembira gembira hajat ibu bapa gagal dapat lesen terima bantuan tertunai mesin jahit muka 14 muka 5 muka 10 DEMAM BOLA... Exco Selangor, Dr Ahmad Yunus Hairi (berbaju kuning, berkaca mata) turut berkongsi kemeriahan menyaksi- kan perlawanan EURO 2012 antara pasukan England dan Perancis di Restoran Hakim Seksyen 7. Restoran ini merupakan salah satu lokasi daripada 10 tempat yang dipilih bagi sesi tontonan yang akan diadakan di sekitar Shah Alam sempena pertandingan piala itu. Sesi ‘Tayangan Wajib Tonton EURO 2012’, dianjurkan Pengerak Belia Tempatan Shah Alam ber- sama Pejabat Exco Adat Resam Melayu, Belia dan Sukan. Selain menonton perlawanan, pengunjung juga berpeluang menyertai pelbagai pertandingan seperti timbang bola, tendangan penalti dan cabutan bertuah Struktur semula cara terbaik urus air, bukan Langat 2 Oleh SHERIDAN MAHAVERA pada pengguna. biran Umno-BN, harga air bersih Fakta di atas merupakan ke- Klang, Charles Santiago dan Ahli Menurut Unit Perancangan mampu melonjak sebanyak 78 simpulan yang boleh diambil da- Parlimen Petaling Jaya Utara, SHAH ALAM - Penstrukturan Ekonomi Negeri (Upen), pen- peratus. ripada Forum Air Selangor pada Tony Pua. semula industri air Selangor strukturan semula akan memas- Tambah lagi, jika penstruk- 12 Jun di Shah Alam. Seorang jurutera dari Coali- merupakan cara terbaik untuk tikan bekalan mencukupi dan turan tidak berlaku dan pro- Forum sehari itu memperli- tion for Sustainable Water Ma- memastikan bekalan air bersih di kadar air tidak berhasil (non- jek mega Langat 2 dibina oleh hatkan pakar industri air terma- nagement (CSWM), Dr Lee Jin Lembah Klang mencukupi untuk revenue water) iaitu, air bersih Umno-BN, harga air mampu me- suk agensi Selangor seperti Lem- mendedahkan laporan yang di- rakyat Selangor pada harga yang yang dibazirkan melalui sistem lonjak sebanyak 100 peratus. -

AKHBAR Selangorkini 29 Januari – 5 Februari 2016

www.selangorku.com MediaSelangorku MediaSelangor tv.selangorku.com PERCUMA 29 Januari - 5 Februari 2016, 19 - 26 Rabiulakhir 1437 #SmartSelangor Tingkat integriti dan profesionalisme penjawat awam Turun padang selami suara rakyat SHAH ALAM - Kepimpinan ne- jah menyelami isu rakyat dengan tempoh begitu lama. Awam dan bersikap profesional jawat awam diingatkan supaya ber- geri dan penjawat awam disaran tidak sekadar duduk di pejabat “Tidak dapat membayangkan tanpa setia kepada orang politik hemah dalam perbelanjaan serta turun padang bagi menghayati mendengar laporan serta taklimat. selepas hampir 60 tahun merdeka, mahupun parti. bekerja dengan baik dan amanah. dan menyelami kesusahan rakyat Katanya, dalam program terja- masih ada rakyat tidak memiliki Katanya, barisan kepimpinan “Rekod kewangan negeri adalah sebelum membuat sesuatu kepu- han itu, beliau terkesan dan sebak kediaman selesa untuk keluarga,” negeri bersilih ganti selepas tamat yang terbaik dalam negara setakat tusan membabitkan kepentingan apabila melihat masih ada kelu- kata Mohamed Azmin semasa Maj- penggal pentadbiran namun pen- ini,” kata Mohamed Azmin. awam. arga di negeri itu yang daif dan ti- lis Penyerahan Hak Milik Tanah di jawat awam kekal terus berkhidmat Selangor mencatat lebihan ke- Menteri Besar, Dato’ Seri Mo- dak dapat pemilikan ke atas tanah Bangi pada 17 Januari lalu. dan beliau tidak mahu ada kakita- wangan berjumlah RM577 juta hamed Azmin Ali, berkata menjadi diteroka. Sebelum ini, Mohamed Azmin ngan awam menjadi ‘kambing hi- selepas penutupan akaun pada 31 tradisi kerja beliau dan pasukan di “Bukan untuk tempoh satu atau mahu penjawat awam berpegang tam’ ekoran kegagalan sistem. Disember 2015 sekaligus menjadi- negeri itu melakukan program ter- dua tahun, bahkan membabitkan kepada Piagam Perkhidmatan Mohamed Azmin berkata pen- kan hasil berjumlah RM2.53 bilion. -

(Gis) Approach for Analyzing Channel Planform Change with Examples of Langat River, Malaysia

ID:327 USE OF GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM (GIS) APPROACH FOR ANALYZING CHANNEL PLANFORM CHANGE WITH EXAMPLES OF LANGAT RIVER, MALAYSIA M.E. Toriman1; M.Mokhtar2; M.B.Gasim3; R. Elfithri2 & Nor Azlina A.B1 1School of Social, Development & Environmental Studies, FSSK, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 43600 Bangi, Selangor 2Institute of Environmental & Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.43600. Bangi Selangor, Malaysia. 3School of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resources, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi Selangor Malaysia 4Fakulti Kejuruteraan Awam, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai Johor, Malaysia This article focuses on the Langat River Channel Planform changes in medium (25 to 100 years) and short time (over last few months to 25 years) scales using Geographical Information System analysis (GIS) involving the cross section and sinuosity analyses. Three sets of topographical maps for three different years (1969, 1976 and 1993) were digitized and rectified and type of changes for the non-stable reaches were defined by superimposing the digital maps of all dates. The results indicate that, middle stream is the most unstable reach followed by upstream which has a few unstable sub-reaches while the downstream shows no changes during the study period. Type of most of the lateral changes for upland reach was meander progression and for middle stream meander progression and avulsion construct most of changes. The middle stream of the channel was identified as the most unstable reach with an average 11.81% change in its sinuosity index. Meanwhile, the upland and downstream of the channel were behaving as more stable reaches with an average 6.92% and 8.47% changes in their sinuosity, respectively. -

ISES 2020 Brochure 05(Separated)

THE 5TH INTERNATIONAL SUSTAINABLE ENERGY SUMMIT 2020 EMPOWERING ENERGY TRANSITION g Energy erin Tran ow si p tio Em n 2020 20th - 21st April 2020 Dewan Jubli Perak Sultan Abdul Aziz Shah Alam, Selangor www.ises.gov.my CO-HOSTED WITH JOINTLY ORGANISED BY ENDORSED BY Selangor State's Environment, Green Technology, Science, Technology and Innovation and Consumer Affairs Committee About 5th ISES 2020 What’s new in 5th ISES? ring Energy Tr we ans po iti The International Sustainable Energy Summit The Authority is pleased to announce that the 5th m on E (ISES) is a knowledge-based platform specifically ISES 2020 will be held in collaboration with both 2020 focusing on renewable energy and energy MESTECC and the Selangor State Government, efficiency. The ISES is organised by the Sustainable through the Environment, Green Technology, Energy Development Authority (‘the Authority’) Science and Consumer Affairs Committee. The Malaysia in collaboration with the Ministry of current Government has set an aspirational Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and target of reaching 20% renewable energy (RE) in Climate Change (MESTECC). The ISES is a biennial the national installed capacity mix by 2025 and event, 2020 will be the 5th summit. The summit this includes hydropower of up to 100 MW. The typically spans over two days and has two key summit will launch the nation’s Renewable components: the knowledge (conference) and Energy Transition Roadmap (RETR) 2035 and business interactions via mini exhibition and part of this roadmap is to address how the 20% business matching session. RE target can be achieved. Guest of Honour YAB. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers

Scam Recycling e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers The e-Trash Transparency Project Front Cover: One of what are believed to be 100’s of electronics junkyards in Hong Kong’s New Territories region, receiving US e-waste. The junkyards break apart the equipment using dangerous, polluting methods. ©BAN 2016 Back Inside Cover: KCTS producer Katie Campbell with Jim Puckett on the trail in New Territories, Hong Kong. ©KCTS, Earthfix Program, 2016. Back Cover: A pile of broken Cold Cathode Fluorescent Lamps (CCFLs) from flat screen monitors imported from the US. CCFLs contain the toxic element mercury. ©BAN 2016. Page 2 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Made Possible by a Grant from: The Body Shop Foundation Basel Action Network 206 1st Ave. S. Seattle, WA 98104 Phone: +1.206.652.5555 Email: [email protected], Web: www.ban.org Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Page 3 Page 4 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Acknowledgements Authors: Eric Hopson, Jim Puckett Editors: Hayley Palmer, Sarah Westervelt Layout & Design: Jennifer Leigh, Eric Hopson Site Investigative Teams Hong Kong: Mr. Jim Puckett, American, Director of the Basel Action Network Ms. Dongxia (Evana) Su, Chinese, journalist and fixer Mr. Sanjiv Pandita, Indian/Hong Kong director of Asia Monitor Resource Centre Mr. Aurangzaib (Ali) Khan, Pakistani/Hong Kong, trader Guiyu, China: Mr. Jim Puckett, American, Director of the Basel Action Network Mr. Michael Standaert, American, journalist, Bloomberg BNA Mr. -

Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-180 ISSUE 16, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Copyright Page Issue 16, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 16, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Table of Contents COMMON LANGUAGE Geographic Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Table of Contents 1.