Language Contact and Substrate in the Languages of Wallacea: Introduction Antoinette Schapper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps Toward a Grammar Embedded in Data Nicholas Thieberger

Steps toward a grammar embedded in data Nicholas Thieberger 1. Introduction 1 Inasmuch as a documentary grammar of a language can be characterized – given the formative nature of the discussion of documentary linguistics (cf. Himmelmann 1998, 2008) – part of it has to be based in the relationship of the analysis to the recorded data, both in the process of conducting the analysis with interactive access to primary recordings and in the presenta- tion of the grammar with references to those recordings. This chapter discusses the method developed for building a corpus of recordings and time-aligned transcripts, and embedding the analysis in that data. Given that the art of grammar writing has received detailed treatment in two recent volumes (Payne and Weber 2006, Ameka, Dench, and Evans 2006), this chapter focuses on the methodology we can bring to developing a grammar embedded in data in the course of language documentation, observing what methods are currently available, and how we can envisage a grammar of the future. The process described here creates archival versions of the primary data while allowing the final work to include playable versions of example sen- tences, in keeping with the understanding that it is our professional respon- sibility to provide the data on which our claims are based. In this way we are shifting the authority of the analysis, which traditionally has been lo- cated only in the linguist’s work, and acknowledging that other analyses are possible using new technologies. The approach discussed in this chap- ter has three main benefits: first, it gives a linguist the means to interact instantly with digital versions of the primary data, indexed by transcripts; second, it allows readers of grammars or other analytical works to verify claims made by access to contextualised primary data (and not just the limited set of data usually presented in a grammar); third, it provides an archival form of the data which can be accessed by speakers of the lan- guage. -

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

Reflections on Linguistic Fieldwork and Language Documentation in Eastern Indonesia

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 15 Reflections on Language Documentation 20 Years after Himmelmann 1998 ed. by Bradley McDonnell, Andrea L. Berez-Kroeker & Gary Holton, pp. 256–266 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 25 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24827 Reflections on linguistic fieldwork and language documentation in eastern Indonesia Yusuf Sawaki Center for Endangered Languages Documentation, University of Papua I Wayan Arka Australia National University Udayana University In this paper, we reflect on linguistic fieldwork and language documentation activities in Eastern Indonesia. We first present the rich linguistic and biological diversity of this region, which is of significant interest in typological and theoretical linguistics and language documentation. We then discuss certain central educational issues in relation to human resources, infrastructures, and institutional support, critical for high quality research and documentation. We argue that the issues are multidimensional and complex across all levels, posing sociocultural challenges in capacity-building programs. Finally, we reflect on the significance of the participation oflocal fieldworkers and communities and their contextual training. 1. Introduction In this paper, we reflect on linguistic fieldwork and language documentation in Eastern Indonesia. By “Eastern Indonesia,” we mean the region that stretches from Nusa Tenggara to Papua,1 including Nusa Tenggara Timur, Sulawesi, and Maluku. This region is linguistically one of the most diverse regions in the world interms of the number of unrelated languages and their structural properties, further discussed in the next section. This is the region where Nikolaus Himmelmann has done his linguistic 1The term “Papua” is potentially confusing because it is used in two senses. -

Helicobacter Pylori in the Indonesian Malay's Descendants Might Be

Syam et al. Gut Pathog (2021) 13:36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-021-00432-6 Gut Pathogens RESEARCH Open Access Helicobacter pylori in the Indonesian Malay’s descendants might be imported from other ethnicities Ari Fahrial Syam1†, Langgeng Agung Waskito2,3†, Yudith Annisa Ayu Rezkitha3,4, Rentha Monica Simamora5, Fauzi Yusuf6, Kanserina Esthera Danchi7, Ahmad Fuad Bakry8, Arnelis9, Erwin Mulya10, Gontar Alamsyah Siregar11, Titong Sugihartono12, Hasan Maulahela1, Dalla Doohan2, Muhammad Miftahussurur3,12* and Yoshio Yamaoka13,14* Abstract Background: Even though the incidence of H. pylori infection among Malays in the Malay Peninsula is low, we observed a high H. pylori prevalence in Sumatra, which is the main residence of Indonesian Malays. H. pylori preva- lence among Indonesian Malay descendants was investigated. Results: Using a combination of fve tests, 232 recruited participants were tested for H- pylori and participants were considered positive if at least one test positive. The results showed that the overall H. pylori prevalence was 17.2%. Participants were then categorized into Malay (Aceh, Malay, and Minang), Java (Javanese and Sundanese), Nias, and Bataknese groups. The prevalence of H. pylori was very low among the Malay group (2.8%) and no H. pylori was observed among the Aceh. Similarly, no H. pylori was observed among the Java group. However, the prevalence of H. pylori was high among the Bataknese (52.2%) and moderate among the Nias (6.1%). Multilocus sequence typing showed that H. pylori in Indonesian Malays classifed as hpEastAsia with a subpopulation of hspMaori, suggesting that the isolated H. pylori were not a specifc Malays H. -

Alex Francois

Alex François LACITO-CNRS, Paris ParallelParallel meanings,meanings, divergentdivergent formsforms inin thethe northnorth VanuatuVanuatu SprachbundSprachbund Diffusion or genetic inheritance? 28 September 2007 — ALT7, Paris ArealAreal studiesstudies andand languagelanguage familiesfamilies Linguistic areas “A linguistic area is generally taken to be a geographically delimited area including languages from two or more language families, sharing significant traits.” [Dixon 2001] “The central feature of a linguistic area is the existence of structural similarities shared among languages of a geographical area, where usually some of the languages are genetically unrelated or at least are not all close relatives.” [Campbell 2006] ‣ Most areal studies involve distinct language families: Balkans, Mesoamerica, Ethiopia, SE Asia, India, Siberia... ‣ Another type: Contact situations involving languages which are genetically closely related. e.g. Heeringa et al. 2000 for Germanic lgs; Chappell 2001 for Sinitic lgs… Structural similarities < common ancestor or diffusion? ‣ This case study: the 17 languages of north Vanuatu. 2 Torres Is. Banks Is. Maewo Santo Ambae Pentecost Malekula Efate Tanna Hiw The 17 languages of north Vanuatu Lo- Toga Löyöp Lehali Volow Mwotlap Lemerig Close genetic relationship Mota Austronesian > Oceanic Veraa > North-Central Vanuatu [Clark 1985] Mwesen > North Vanuatu [François 2005] Vurës Sustained language contact and plurilingualism through trade, exogamy, shared cultural events… [Vienne 1984] Nume Little mutual intelligibility -

LACITO - Laboratoire De Langues & Civilisations À Tradition Orale Rapport Hcéres

LACITO - Laboratoire de langues & civilisations à tradition orale Rapport Hcéres To cite this version: Rapport d’évaluation d’une entité de recherche. LACITO - Laboratoire de langues & civilisations à tradition orale. 2018, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, Centre national de la recherche scien- tifique - CNRS, Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales - INALCO. hceres-02031755 HAL Id: hceres-02031755 https://hal-hceres.archives-ouvertes.fr/hceres-02031755 Submitted on 20 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Research evaluation REPORT ON THE RESEARCH UNIT: Langues et Civilisations à Tradition Orale LaCiTO UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF THE FOLLOWING INSTITUTIONS AND RESEARCH BODIES: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales – INALCO Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique – CNRS EVALUATION CAMPAIGN 2017-2018 GROUP D In the name of Hcéres1 : In the name of the experts committees2 : Michel Cosnard, President Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Chairman of the committee Under the decree No.2014-1365 dated 14 november 2014, 1 The president of HCERES "countersigns the evaluation reports set up by the experts committees and signed by their chairman." (Article 8, paragraph 5) ; 2 The evaluation reports "are signed by the chairman of the expert committee". -

In Antoinette SCHAPPER, Ed., Contact and Substrate in the Languages of Wallacea PART 1

Contact and substrate in the languages of Wallacea: Introduction Antoinette SCHAPPER KITLV & University of Cologne 1. What is Wallacea?1 The term “Wallacea” originally refers to a zoogeographical area located between the ancient continents of Sundaland (the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and Bali) and Sahul (Australia and New Guinea) (Dickerson 1928). Wallacea includes Sulawesi, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Sumba, Timor, Halmahera, Buru, Seram, and many smaller islands of eastern Indonesia and independent Timor-Leste (Map 1). What characterises this region is its diverse biota drawn from both the Southeast Asian and Australian areas. This volume uses the term Wallacea to refer to a linguistic area (Schapper 2015). In linguistic terms as in biogeography, Wallacea constitutes a transition zone, a region in which we observe the progression attenuation of the Southeast Asian linguistic type to that of a Melanesian linguistic type (Gil 2015). Centred further to the east than Biological Wallacea, Linguistic Wallacea takes in the Papuan and Austronesian languages in the region of eastern Nusantara including the Minor Sundic Islands east of Lombok, Timor-Leste, Maluku, the Bird’s Head and Neck of New Guinea, and Cenderawasih Bay (Map 2). Map 1. Biological Wallacea Map 2. Linguistic Wallacea 1 My editing and research for this issue has been supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research VENI project “The evolution of the lexicon. Explorations in lexical stability, semantic shift and borrowing in a Papuan language family” and by the Volkswagen Stiftung DoBeS project “Aru languages documentation”. Many thanks to Asako Shiohara and Yanti for giving me the opportunity to work with them on editing this NUSA special issue. -

Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: Effects of Altitude, the 1815 Cataclysmic Volcanic Eruption and Trade

FORKTAIL 18 (2002): 49–61 Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade COLIN R. TRAINOR In June-July 2000, a 10-day avifaunal survey on Gunung Tambora (2,850 m, site of the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history), revealed an extraordinary mountain with a rather ordinary Sumbawan avifauna: low in total species number, with all species except two oriental montane specialists (Sunda Bush Warbler Cettia vulcania and Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophrys) occurring widely elsewhere on Sumbawa. Only 11 of 19 restricted-range bird species known for Sumbawa were recorded, with several exceptional absences speculated to result from the eruption. These included: Flores Green Pigeon Treron floris, Russet-capped Tesia Tesia everetti, Bare-throated Whistler Pachycephala nudigula, Flame-breasted Sunbird Nectarinia solaris, Yellow-browed White- eye Lophozosterops superciliaris and Scaly-crowned Honeyeater Lichmera lombokia. All 11 resticted- range species occurred at 1,200-1,600 m, and ten were found above 1,600 m, highlighting the conservation significance of hill and montane habitat. Populations of the Yellow-crested Cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea, Hill Myna Gracula religiosa, Chestnut-backed Thrush Zoothera dohertyi and Chestnut-capped Thrush Zoothera interpres have been greatly reduced by bird trade and hunting in the Tambora Important Bird Area, as has occurred through much of Nusa Tenggara. ‘in its fury, the eruption spared, of the inhabitants, not a although in other places some vegetation had re- single person, of the fauna, not a worm, of the flora, not a established (Vetter 1820 quoted in de Jong Boers 1995). blade of grass’ Francis (1831) in de Jong Boers (1995), Nine years after the eruption the former kingdoms of referring to the 1815 Tambora eruption. -

A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Eeds Dispersal Melissa E

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 5-24-2017 A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their eedS Dispersal Melissa E. Abdo Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001976 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Abdo, Melissa E., "A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their eS ed Dispersal" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3355. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3355 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida A FLORISTIC STUDY OF HALMAHERA, INDONESIA FOCUSING ON PALMS (ARECACEAE) AND THEIR SEED DISPERSAL A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in BIOLOGY by Melissa E. Abdo 2017 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Melissa E. Abdo, and entitled A Floristic Study of Halmahera, Indonesia Focusing on Palms (Arecaceae) and Their Seed Dispersal, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Javier Francisco-Ortega _______________________________________ Joel Heinen _______________________________________ Suzanne Koptur _______________________________________ Scott Zona _______________________________________ Hong Liu, Major Professor Date of Defense: May 24, 2017 The dissertation of Melissa E. -

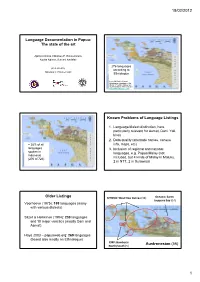

Language Documentation in Papua: the State of the Art

18/02/2012 Language Documentation in Papua: The state of the art Apriani Arilaha, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Novita Ndiken, Sutriani Narfafan 276 languages presented by according to Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Ethnologue Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/ Known Problems of Language Listings 1. Language/dialect distinction, here particularly relevant for Asmat, Dani, Yali, Irires 2. Data quality (alternate names, census = 38% of all info, maps, etc) languages 3. Inclusion of regional and national spoken in languages, e.g. Papua Malay (not Indonesia (276 of 726) included, but 4 kinds of Malay in Maluku, 2 in NTT, 2 in Sulawesi) Older Listings SHWNG: West New Guinea (34) Oceanic: Sarmi Jayapura Bay (14) Voorhoeve (1975): 199 languages (many ? with various dialects) Silzer & Heikkinen (1984): 230 languages and 10 major varieties (mostly Dani and Asmat). Hays 2003 – papuaweb.org: 269 languages (based also mostly on Ethnologue) CMP: Bomberai Austronesian (56) North/South (5) 1 18/02/2012 Papuan Languages (220) Speaker numbers Lakes Plain (20) Tor Kwerba (24) Largest, smallest, mean, median Trans‐New Guinea (93) Administrative structure of Irian Jaya before Sociopolitical Setting 1998 (?): 1 Province, 12 Kabupaten Kab. Biak Numfor Accelerating change in the last 150 years: Kab. Manokwari Kab. Sorong Kab. Yapen Waropen - Christian mission since 1855, last ‘first’ Kab. Jayapura Kab. Nabire contacts in the late 1970s Kab. Puncak Jaya Kab. Fakfak Kab. Paniai - Dutch colonial rule 1898 till 1962 Kab. Jayawijaya Kab. Mimika - Indonesiasikan 1962-1998 Kab. Merauke - Otonomi daerah 2001-?? PROVINSI PAPUA Demographic change Population figures 1988/2010 2010 1988 Papua Papua Barat (Irian Jaya) Rural Urban Rural Urban PROVINSI PAPUA BARAT 2.097.752 735.629 532.659 227.763 2.833.381 760.422 Now 2 Provinces with all 1,452,900 3,593,803 together 28 Kabupaten (19 Kabupaten in Papua and 9 Kabupaten in Papua Barat). -

Volume 4-2:2011

JSEALS Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Managing Editor: Paul Sidwell (Pacific Linguistics, Canberra) Editorial Advisory Board: Mark Alves (USA) George Bedell (Thailand) Marc Brunelle (Canada) Gerard Diffloth (Cambodia) Marlys Macken (USA) Brian Migliazza (USA) Keralapura Nagaraja (India) Peter Norquest (USA) Amara Prasithrathsint (Thailand) Martha Ratliff (USA) Sophana Srichampa (Thailand) Justin Watkins (UK) JSEALS is the peer-reviewed journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, and is devoted to publishing research on the languages of mainland and insular Southeast Asia. It is an electronic journal, distributed freely by Pacific Linguistics (www.pacling.com) and the JSEALS website (jseals.org). JSEALS was formally established by decision of the SEALS 17 meeting, held at the University of Maryland in September 2007. It supersedes the Conference Proceedings, previously published by Arizona State University and later by Pacific Linguistics. JSEALS welcomes articles that are topical, focused on linguistic (as opposed to cultural or anthropological) issues, and which further the lively debate that characterizes the annual SEALS conferences. Although we expect in practice that most JSEALS articles will have been presented and discussed at the SEALS conference, submission is open to all regardless of their participation in SEALS meetings. Papers are expected to be written in English. Each paper is reviewed by at least two scholars, usually a member of the Advisory Board and one or more independent readers. Reviewers are volunteers, and we are grateful for their assistance in ensuring the quality of this publication. As an additional service we also admit data papers, reports and notes, subject to an internal review process. -

Avifauna Diversity at Central Halmahera North Maluku, Indonesia Zoo Indonesia 2012

Avifauna Diversity at Central Halmahera North Maluku, Indonesia Zoo Indonesia 2012. 21(1): 17-31 AVIFAUNA DIVERSITY AT CENTRAL HALMAHERA NORTH MALUKU, INDONESIA Mohammad Irham Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences Widyasatwaloka Building, Jl. Raya Jakarta-Bogor Km. 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia Email: [email protected] ABSTRAK Irham, M. Keanekaragaman Avifauna at Weda Bay, Halmahera, Indonesia. 2012 Zoo Indonesia 21(1), 17-31. Survei burung dengan menggunakan metode titik hitung dan jaring telah dilakukan di Halmahera, Maluku Utara di empat lokasi utama yaitu Wosea, Ake Jira, Tofu Blewen dan Bokit Mekot. Sebanyak 70 spesies burung dari 32 famili dijumpai selama penelitian lapangan. Keragaman burung tertinggi ditemukan di Tofu Blewen yaitu 50 spesies (Indeks Shannon = 2.64) kemudian diikuti oleh Ake Jira (48 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,63), Wosea (41 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,54) dan Boki Mekot (37 spesies, Indeks Shannon = 2,52 ). Berdasarkan Indeks Kesamaan Jaccard, komunitas burung di Wosea jauh berbeda dibandingkan lokasi lain. Gangguan habitat dan ketinggian memperlihatkan pengaruh pada keragaman burung terutama pada jenis-jenis endemik dan terancam seperti komunitas di Wosea. Beberapa jenis burung, terutama paruh bengkok seperti Kakatua Putih, menunjukkan hubungan negatif dengan ketinggian . Kata Kunci: keragaman burung, Halmahera, gangguan habitat, ketinggian ABSTRACT Irham, M. Avifauna diversity at Weda Bay, Halmahera, Indonesia. 2012 Zoo Indonesia 21(1), 17-31. Bird surveys by point counts and mist-nets were carried out in Halmahera, North Moluccas at four locations i.e. Wosea, Ake Jira, Tofu Blewen and Bokit Mekot. A total of 70 birds species from 32 families were recorded during fieldworks.