Importers, Exporters, and Multinationals: a Portrait of Firms In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gold Cadillac Gold the C 6 READING FOCUS E - S 0 S 2

The Gold Cadillac by Mildred D. Taylor BACKGROUND The novella The Gold Cadillac takes place around 1950. African Americans, especially those living in the South during this time, continued to be treated unfairly. Experiences like the one the family in the story has when entering Mississippi outraged blacks and many whites. During the Civil Rights Era of the mid-1950s and 1960s, many people demanded changes in the laws across the nation. My sister and I were playing out on the front lawn when the gold A READING FOCUS Cadillac rolled up and my father stepped from behind the wheel. How do you predict ‘lois, We ran to him, our eyes filled with wonder. “Daddy, whose Wilma, and their mother will Cadillac?” I asked. feel about the new Cadillac? And Wilma demanded, “Where’s our Mercury?” My father grinned. “Go get your mother and I’ll tell you all about it.” “Is it ours?” I cried. “Daddy, is it ours?” “Get your mother!” he laughed. “And tell her to hurry!” 10 Wilma and I ran off to obey, as Mr. Pondexter next door came from his house to see what this new Cadillac was all about. We threw open the front door, ran through the downstairs front parlor and straight through the house to the kitchen, where my mother was cooking and one of my aunts was helping her. “Come on, Mother-Dear!” we cried together. “Daddy say come on out and see this new car!” A “What?” said my mother, her face showing her surprise. “What’re you talking about?” Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. -

2021 Cadillac XT4 Owner's Manual

21_CAD_XT4_COV_en_US_84533014B_2020OCT27.pdf 1 9/25/2020 1:45:28 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 84533014 B Cadillac XT4 Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada/Mexico- 14584367) - 2021 - CRC - 10/14/20 Introduction model variants, country specifications, Contents features/applications that may not be available in your region, or changes Introduction . 1 subsequent to the printing of this owner’s manual. Keys, Doors, and Windows . 6 Refer to the purchase documentation Seats and Restraints . 36 relating to your specific vehicle to Storage . 84 confirm the features. Instruments and Controls . 90 The names, logos, emblems, slogans, Keep this manual in the vehicle for vehicle model names, and vehicle quick reference. Lighting . 129 body designs appearing in this manual Infotainment System . 136 including, but not limited to, GM, the Canadian Vehicle Owners GM logo, CADILLAC, the CADILLAC Climate Controls . 197 A French language manual can be Emblem, and XT4 are trademarks and/ obtained from your dealer, at Driving and Operating . 203 or service marks of General Motors www.helminc.com, or from: LLC, its subsidiaries, affiliates, Vehicle Care . 281 or licensors. Propriétaires Canadiens Service and Maintenance . 357 For vehicles first sold in Canada, On peut obtenir un exemplaire de ce Technical Data . 370 substitute the name “General Motors guide en français auprès du ” Customer Information . 374 of Canada Company for Cadillac concessionnaire ou à l'adresse Motor Car Division wherever it suivante: Reporting Safety Defects . 384 appears in this manual. Helm, Incorporated OnStar . 387 This manual describes features that Attention: Customer Service Connected Services . 392 may or may not be on the vehicle 47911 Halyard Drive because of optional equipment that Plymouth, MI 48170 Index . -

2004 Cadillac Escalade EXT Owner Manual M

2004 Cadillac Escalade EXT Owner Manual M Seats and Restraint Systems ........................... 1-1 Driving Your Vehicle ....................................... 4-1 Front Seats ............................................... 1-2 Your Driving, the Road, and Your Vehicle ..... 4-2 Rear Seats ............................................... 1-6 Towing ................................................... 4-46 Safety Belts .............................................. 1-8 Service and Appearance Care .......................... 5-1 Child Restraints ....................................... 1-28 Service ..................................................... 5-3 Air Bag Systems ...................................... 1-48 Fuel ......................................................... 5-4 Restraint System Check ............................ 1-61 Checking Things Under the Hood ................. 5-8 Features and Controls ..................................... 2-1 All-Wheel Drive ........................................ 5-48 Keys ........................................................ 2-3 Rear Axle ............................................... 5-49 Doors and Locks ....................................... 2-8 Front Axle ............................................... 5-50 Windows ................................................. 2-25 Headlamp Aiming ..................................... 5-51 Theft-Deterrent Systems ............................ 2-27 Bulb Replacement .................................... 5-55 Starting and Operating Your Vehicle .......... -

A Picture Perfect 1932 Lincoln KB Sport Phaeton

Volume 20 Issue 9 September 1, 2020 A picture perfect 1932 Lincoln KB Sport Phaeton The Pride and Joy of Lou and Judi Cosentino In March of 2018, we went to our first major auto auction and show in Amelia Island, Flori- da. We became interested in antique autos after visiting John Staluppi’s Cars of Dreams in North Palm Beach, Florida. We had acquired a 1931 Packard Super 8 and loved the cars of the 1930s. The 1932 Lincoln KB Sport Phaeton was gorgeous, but did not draw significant interest from bidders. We were surprised, jumped in, and won the bid. Welcome to the The KB 232-B Sport was designed by the Walter M. Murphy Company in Pasadena, Califor- Northstar News, the nia, and constructed in Lincoln’s own body plant. Lincoln made eight-cylinder (KA) and 12- cylinder (KB) cars in 1932. This was the first year that Lincoln offered 12-cylinder engines. Lin- monthly publication of coln produced 43 KB Phaetons that year, and of these, only 13 were Sport Phaetons. This model the Northstar Region was almost identical to the Dual Cowl Sport Phaeton, lacking only the tonneau cowl. We were of the Lincoln and told this is the only survivor of this body type. The base price of the Sport Phaeton in 1932 was $4500. It is recognized as a Full Classic by the Classic Car Club of America. Continental Owners We were pleased to find that this car was previously owned by a Minnesotan, Jim Griffin, a Club. We value your Lincoln historian. -

2020 Cadillac XT6 Owners Manual

20_CAD_XT6_COV_en_US_84321179B_2019AUG07.ai 1 8/7/2019 11:15:21 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 84321179 B Cadillac XT6 Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada-12984300) - 2020 - CRC - 8/1/19 Contents Introduction . 2 Keys, Doors, and Windows . 7 Seats and Restraints . 41 Storage . 96 Instruments and Controls . 104 Lighting . 145 Infotainment System . 152 Climate Controls . 153 Driving and Operating . 163 Vehicle Care . 254 Service and Maintenance . 328 Technical Data . 342 Customer Information . 345 Reporting Safety Defects . 356 OnStar . 360 Connected Services . 368 Index . 371 Cadillac XT6 Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada-12984300) - 2020 - CRC - 8/1/19 2 INTRODUCTION Introduction was not purchased on the vehicle, Helm, Incorporated model variants, country specifications, Attention: Customer Service features/applications that may not be 47911 Halyard Drive available in your region, or changes Plymouth, MI 48170 subsequent to the printing of this USA owner’s manual. Refer to the purchase documentation Using this Manual relating to your specific vehicle to To quickly locate information about confirm the features. the vehicle, use the Index in the back The names, logos, emblems, slogans, of the manual. It is an alphabetical vehicle model names, and vehicle Keep this manual in the vehicle for list of what is in the manual and the body designs appearing in this manual quick reference. page number where it can be found. including, but not limited to, GM, the Canadian Vehicle Owners GM logo, CADILLAC, the CADILLAC Danger, Warning, and Emblem, and XT6 are trademarks and/ A French language manual can be or service marks of General Motors obtained from your dealer, at Caution LLC, its subsidiaries, affiliates, www.helminc.com, or from: Warning messages found on vehicle or licensors. -

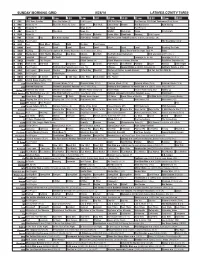

Sunday Morning Grid 8/28/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/28/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PBR Bull Riding The Barclays 2016 Golf Tournament Final Round. 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Ruff-Ruff, Chica Show Noodle Red Bull Series Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Wildlife Rock-Park Tennis 2016 LLWS 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday FOX College Football NFL Preseason Football Chargers at Minnesota Vikings. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Dead Zone ››› 18 KSCI Paid Mom Mkver Church Faith Dr. John Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Breaking The Code 24 KVCR Healing The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. (TVG) Super Brain With Dr. Rudy Tanzi Å Yakov 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ The Truth About Retirement ADD and Loving It?! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage The Toy Job. Leverage (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Belgian Grand Prix. -

Farewell to a Great

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U DAILY BRIEFING, A2 • TRIBUTES, A6 • WORLD, A8 • BUSINESS, B5 • CLASSIFIEDS, B6 • PUZZLES, C3 KEEPING HIS NFL DREAMS ALIVE BALLOT PROPOSALS GOOD DAY’S WORK 50% Boardman grad excels in AFL Group turns in petitions to clerk Critic: Salem’s ‘9 to 5’ thrives OFF SPORTS | B1 LOCAL | A5 VALLEY LIFE | C1 vouchers. DETAILS, A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 TUESDAY, AUGUST 8, 2017 U 75¢ Warren police: Shooting deaths of 3 in car involved no one else By ED RUNYAN volve anybody else,” Kistler said Monday. nounced dead at the scene. West was the [email protected] Kistler said it’s too soon to discuss who did driver of the car, which was owned by his WARREN the shooting or what led up to it. girlfriend, who was not in the car. Police say the Thursday night shooting One gun was found in the car when police Ju’wantae A. Harbin, 18, of Douglas Street deaths of two men and a woman in a car on arrived for the 7:13 p.m. shootings, Kistler Northwest, a passenger, was pronounced Southern Boulevard Northwest was “at least said. The shootings occurred just before and dead later at St. Elizabeth Youngstown Hos- a double” homicide and involved only the just after the Cadillac crashed into the side pital. three people who died. West Joseph Harbin of a house at the corner of Southern Boule- The crash caused minor damage to the It could end up being ruled a triple ho- vard and Solar Street Northwest. -

Motoring Memories

MOTORING MEMORIES ONE MOTORIST’S EXPERIENCES i TABLE OF CONTENTS Motoring Memories 1 1954 Packard Clipper Deluxe Sedan 2 1956 Buick Century Riviera Coupe 16 Also Rans 23 1973 Buick Riviera 26 1979 Oldsmobile 98 Regency Sedan 28 1978 Cadillac DeVille Sedan 30 Other Cadillacs 32 1983 Ford Mustang GLX Convertible 33 1961 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II Sedan 34 Other People’s Cars 42 Grandfather White 42 The Pierce Arrow 43 Sylvia’s Hudson 44 ii My Father’s Riders 45 Clem’s Studebaker 46 My Parents’ 1955 Chevrolet 46 The Plymouth Valiant 48 More Packard Tales 48 Governor Browning’s Cadillac 49 The Cadillacs of Kroger 49 The Packards of Kroger 51 The Rolls-Royces of Kroger 53 The 1962 Buick Electra 54 Hodo’s Ford 55 The English Rental 57 Finale, For the Moment 58 iii MOTORING MEMORIES Motoring is an experience with an automobile, something that makes one=s interaction with an automobile memorable. It can be good or bad, a life changing experience, or just a memorable event or occasion. It can fix in your memory a series of sights, smells, and associations that linger there forever. Driving is just the function of taking a car from one place to another. Most of the time all of us merely drive, but there are times when we motor memorably. These are some of those stories. I cannot remember a time when cars were not important to me. After AMama@ and ADaddy,@ I am told that some of the first words I learned to say were ABuick@ and ADeSoto,@ cars then driven by two of the members of my family who drove me around a lot. -

Inventing the Abbotts

INVENTING THE ABBOTTS Screenplay by Ken Hixon From the Short Story by Sue Miller March 21, 1996 DRAFT FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY INVENTING THE ABBOTTS FADE IN: 1EXT. ABBOTT HOME - STREET (HALEY, ILLINOIS) - DAY 1 (LATE SPRING, 1957) OPENING CREDITS ROLL over a TENT MONTAGE -- ASSORTED ANGLES of a group of men hard at work erecting a large striped "big-top" style canvas tent, INCLUDING: The long steel stakes being sledge-hammered into the lawn, practiced hands rapidly rigging the lines, the tall center poles being leveraged upright, the heavy rolled-up sections of canvas being maneuvered into position, and ENDING WITH the canvas being hoisted up the poles as the tent assumes its full and finished form. NEW ANGLE - TENT -- on the front yard of the Abbott mansion. The residence is on Main Street, four blocks from where the commercial district begins. The mature, over-arching trees makes this street of prosperous houses a grand promenade. 2EXT. ABBOTT HOME - STREET - DAY 2 JACEY HOLT and DOUG HOLT walk along the sidewalk on their way to school. Jacey is seventeen; he's as handsome and seemingly self-confident as his younger brother is rumpled and impulsive. Doug is fifteen, a popular culture chameleon who takes on the colors and affectations of whomever his "hero" is at the moment (which presently happens to be Elvis Presley). Jacey stops and stares with open-faced misery at the tent on the Abbott's front yard (the installation of the tent indicates that the Abbott's are having yet another of the many parties they throw every year). -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Šárka Tripesová The Anatomy of Humour in the Situation Comedy Seinfeld Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Šárka Tripesová ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. for the invaluable guidance he provided me as a supervisor. Also, my special thanks go to my boyfriend and friends for their helpful discussions and to my family for their support. iii Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SEINFELD AS A SITUATION COMEDY 3 2.1 SEINFELD SERIES: THE REALITY AND THE SHOW 3 2.2 SITUATION COMEDY 6 2.3 THE PROCESS OF CREATING A SEINFELD EPISODE 8 2.4 METATHEATRICAL APPROACH 9 2.5 THE DEPICTION OF CHARACTERS 10 3 THE TECHNIQUES OF HUMOUR DELIVERY 12 3.1 VERBAL TECHNIQUES 12 3.1.1 DIALOGUES 12 3.1.2 MONOLOGUES 17 3.2 NON-VERBAL TECHNIQUES 20 3.2.1 PHYSICAL COMEDY AND PANTOMIMIC FEATURES 20 3.2.2 MONTAGE 24 3.3 COMBINED TECHNIQUES 27 3.3.1 GAG 27 4 THE METHODS CAUSING COMICAL EFFECT 30 4.1 SEINFELD LANGUAGE 30 4.2 METAPHORICAL EXPRESSION 32 4.3 THE TWIST OF PERSPECTIVE 35 4.4 CONTRAST 40 iv 4.5 EXAGGERATION AND CARICATURE 43 4.6 STAND-UP 47 4.7 RUNNING GAG 49 4.8 RIDICULE AND SELF-RIDICULE 50 5 CONCLUSION 59 6 SUMMARY 60 7 SHRNUTÍ 61 8 PRIMARY SOURCES 62 9 REFERENCES 70 v 1 Introduction Everyone as a member of society experiences everyday routine and recurring events. -

Sydney Program Guide

10/28/2020 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=15-Nov-20&psEndDate=2… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 15th November 2020 06:00 am Charmed (Rpt) CC PG The Good, The Bad & The Cursed Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes When Phoebe sees ghosts in a deserted town, Prue travels back in time to the mid-1800s to save an American Indian from a local thug. Starring: Shannen Doherty, Alyssa Milano, Holly Marie Combs 07:00 am Friends (Rpt) CC PG The One After The Superbowl Part Two WS Rachel and Monica compete for the affections of Jean-Claude Van Damme after meeting him on a movie set. Chandler meets a former schoolmate and Ross and Marcel go on a whirlwind tour of the city. Starring: David Schwimmer, Jennifer Aniston, Matthew Perry, Courteney Cox, Matt LeBlanc, Lisa Kudrow Guest Starring: Julia Roberts, Jean-Claude Van Damme 07:30 am Friends (Rpt) CC PG The One With The Prom Video WS After getting his big break on Days of Our Lives, Joey pays Chandler back with $812 and an extremely tacky bracelet. Monica and Rachel's prom video reveals Monica's former girth, Rachel's former nose and the way Ross has always felt about Rachel. Starring: David Schwimmer, Jennifer Aniston, Matthew Perry, Courteney Cox, Matt LeBlanc, Lisa Kudrow Guest Starring: Elliott Gould, Christina Pickles 08:00 am Rules Of Engagement (Rpt) CC PG The Score Sexual References WS Jeff spends the evening trying to avoid learning the score of a Rangers game after Audrey forces him to give up his tickets and go to her boss' party instead. -

2009 Cadillac CTS Owner Manual

2009 Cadillac CTS/CTS-V Owner Manual M Seats and Restraint System ............................. 1-1 Driving Your Vehicle ....................................... 4-1 Head Restraints ......................................... 1-2 Your Driving, the Road, and the Vehicle ....... 4-2 Front Seats ............................................... 1-4 Towing ................................................... 4-26 Rear Seats .............................................. 1-13 Service and Appearance Care .......................... 5-1 Safety Belts ............................................. 1-14 Service ..................................................... 5-4 Child Restraints ....................................... 1-33 Fuel ......................................................... 5-6 Airbag System ......................................... 1-55 Checking Things Under the Hood ............... 5-12 Restraint System Check ............................ 1-71 All-Wheel Drive ........................................ 5-53 Features and Controls ..................................... 2-1 Rear Axle ............................................... 5-54 Keys ........................................................ 2-3 Headlamp Aiming ..................................... 5-55 Doors and Locks ...................................... 2-17 Bulb Replacement .................................... 5-58 Windows ................................................. 2-23 Windshield Wiper Blade Replacement ......... 5-61 Theft-Deterrent Systems ............................ 2-27