Crazy People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lifelines 2004 a Dartmouth Medical School Literary Journal

Lifelines 2004 A Dartmouth Medical School Literary Journal Major support for this issue comes from: The Fannie and Alan Leslie Center for the Humanities at Dartmouth College and The Allen and Joan Bildner Endowment for Human and Inter-group Relations Sai Li Editor-in-Chief Meghan McCoy Allison Giordano Editor, Artwork and Photography Khalil Ayvar Undergraduate Liaisons Christy Paiva Andy Nordhoff Lori Alvord, MD Assistant Editors Stefan Balan, MD Donna DiFillippo Hiliary Plioplys Sue Ann Hennessy Copy Editor Donald Kollisch, MD Rodwell Mabaera Rodwell Mabaera Meghan McCoy Meghan McCoy Andy Nordhoff Design and Layout Joseph O’Donnell, MD Shawn O’Leary Lisanne Palomar Christy Paiva Publicity Director Hiliary Pliophys Parker Towle, MD Shawn O’Leary Editorial Board, Poetry and Prose Donna DiFillippo Administrative Advisors Joseph Dwaihy Sara Dykstra Lori Alvord, MD Kristin Elias Joseph O’Donnell, MD Rodwell Mabaera Faculty Advisors Editorial Board, Artwork and Photography Copyright ©2004 Trustees of Dartmouth College. All rights reserved. Cover Art “Contemplation Before Surgery” Joe Wilder, M.D. October 5, 1920 – July 1, 2003 Joseph Richard Wilder was born in Baltimore on October 5, 1920. He attended Dartmouth College, University of Pennsylvania, and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Joseph Wilder, athlete, surgeon, and artist, rose to the top of three professions. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Lacrosse in 1987 and received the Markel Award for cardio-vascular research in 1954. His paintings were exhibited at galleries and museums all over the world, including The Museum of Modern Art in New York and The National Portrait Gallery in Washington. -

The Gold Cadillac Gold the C 6 READING FOCUS E - S 0 S 2

The Gold Cadillac by Mildred D. Taylor BACKGROUND The novella The Gold Cadillac takes place around 1950. African Americans, especially those living in the South during this time, continued to be treated unfairly. Experiences like the one the family in the story has when entering Mississippi outraged blacks and many whites. During the Civil Rights Era of the mid-1950s and 1960s, many people demanded changes in the laws across the nation. My sister and I were playing out on the front lawn when the gold A READING FOCUS Cadillac rolled up and my father stepped from behind the wheel. How do you predict ‘lois, We ran to him, our eyes filled with wonder. “Daddy, whose Wilma, and their mother will Cadillac?” I asked. feel about the new Cadillac? And Wilma demanded, “Where’s our Mercury?” My father grinned. “Go get your mother and I’ll tell you all about it.” “Is it ours?” I cried. “Daddy, is it ours?” “Get your mother!” he laughed. “And tell her to hurry!” 10 Wilma and I ran off to obey, as Mr. Pondexter next door came from his house to see what this new Cadillac was all about. We threw open the front door, ran through the downstairs front parlor and straight through the house to the kitchen, where my mother was cooking and one of my aunts was helping her. “Come on, Mother-Dear!” we cried together. “Daddy say come on out and see this new car!” A “What?” said my mother, her face showing her surprise. “What’re you talking about?” Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. -

VILLAGE of BERKELEY AGENDA Tuesday, April 6, 2021 6:30 P.M

VILLAGE OF BERKELEY AGENDA Tuesday, April 6, 2021 6:30 p.m. Village Hall 5819 Electric Avenue Berkeley, Illinois Physical attendance at this public meeting is limited to 50 individuals, with Village officials, staff and consultants having priority over members of the public. Public comments and any responses will be distributed to Village officials. You may submit your public comments via email in advance of the meeting to Rudy Espiritu, Village Administrator at [email protected]. 1 Call to Order 2 Pledge of Allegiance 3 Roll Call 4 Presentations and Appointment 4.1 Village of Berkeley Partner Agency Annual Reports 4.1.1 Berkeley Little League 5 Public Hearings 6 Public Comments and Questions (Consent Agenda Items Only) Please limit comments to five (5) minutes in length, unless further granted by the Board. 7 Consent Agenda The matters listed for consideration on the Consent Agenda are routine in nature or have all been discussed by the Board of Trustees previously and are matters on which there was unanimity for placement on the Consent Agenda at this meeting. 7.1 Village Board Meeting Minutes from March 16, 2021 7.2 Executive Session Meeting Minutes from March 16, 2021 (Not for public release) 7.3 Planning and Zoning Commission Minutes from March 23, 2021 8 Claims Ordinance 8.1 Motion to Approve Claims Ordinance #1460 in the amount of $200,635.85 Note: The Village of Berkeley, in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), requests that any persons with disabilities, who have questions about the accessibility of the meeting or facility, contact Village Hall at 708-449-8840, to allow for reasonable accommodations to be made. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Space Governance of the American Handicapped Parking Space

Law Text Culture Volume 9 Legal Spaces Article 8 2005 Wheelchair as semiotic: space governance of the American handicapped parking space S. Marusek University of Massachusetts, US Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Marusek, S., Wheelchair as semiotic: space governance of the American handicapped parking space, Law Text Culture, 9, 2005. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol9/iss1/8 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Wheelchair as semiotic: space governance of the American handicapped parking space Abstract The wheelchair has become a stereotypical symbol of physical disability. The image may appear as a picture, as on parking signs with a blue background and a white figure sitting in a wheelchair, or in reality when one sees an actual person sitting in one. Both images are useful in characterising the governance of the handicapped parking space, a field that presents a unique case study in the interpretation and enforcement of law. The parking space is legally reserved for vehicles marked by the Blue Wheelchair which hangs as a tag from the rearview mirror or on the licence plate; but at the same time it is socially reserved for vehicles driven by a person who is dependent upon an actual wheelchair. Law enforces this space formally by ticketing and/or towing violating vehicles. Society enforces this space informally through the disciplining gaze of onlookers. Legal enforcement is based upon the presence of the Blue Wheelchair symbol as it matches the sign that towers above the reserved spot. -

Q1 What Time Did You Park/What Time Was This Survey Taken?

Issaquah Park & Ride User Survey Q1 What time did you park/What time was this survey taken? Answered: 413 Skipped: 7 7-7:30 7:30-8 8-8:30 8:30-9 9-9:30 9:30-10:00 10:00-10:30 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES 7-7:30 17.68% 73 7:30-8 20.10% 83 8-8:30 21.55% 89 8:30-9 23.73% 98 9-9:30 11.86% 49 9:30-10:00 3.15% 13 10:00-10:30 1.94% 8 TOTAL 413 1 / 27 Issaquah Park & Ride User Survey Q2 Which Park & Ride did you use this morning? Answered: 420 Skipped: 0 Issaquah Transit Cent... Highlands Transit Cent... 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Issaquah Transit Center (along Newport Way) 31.43% 132 Highlands Transit Center (along Highlands Drive) 68.57% 288 TOTAL 420 2 / 27 Issaquah Park & Ride User Survey Q3 How did you get to the Park & Ride this morning? Answered: 420 Skipped: 0 Drove alone and parked Carpooled and parked Dropped off by someone I know Dropped off by a taxi, Uber... Transferred from another... Rode a bicycle Walked/wheelcha ir Other (please specify) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Drove alone and parked 73.57% 309 Carpooled and parked 3.33% 14 Dropped off by someone I know 9.52% 40 Dropped off by a taxi, Uber, or Lyft 0.48% 2 Transferred from another bus 4.52% 19 Rode a bicycle 0.24% 1 Walked/wheelchair 8.33% 35 Other (please specify) 0.00% 0 TOTAL 420 # OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY) DATE There are no responses. -

Sydney Program Guide

12/10/2019 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=29-Dec-19&psEndDate=0… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 29th December 2019 06:00 am Toasted TV Toasted TV Sunday 2020 1 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am The Amazing Spiez (Rpt) G Scary Jerry Pt.1 Jerry wakes up with amnesia after an accident. Meanwhile, the kids mistakenly release Jerry's sister from prison. 06:30 am Totally Spies (Rpt) G Another Evil Boyfriend When the girls go on a routine mission to stake out a baddie, Clover suddenly finds herself under attack from an unseen henchman... or so she thinks. 06:55 am Toasted TV Toasted TV Sunday 2020 2 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:00 am Cardfight!! Vanguard G: Next (Rpt) G Overcoming Heaven's Decree Shion, who overcomes any and all adversities, and Kazumi, who wishes to rebel against his fate, fight fiercer than ever. 07:25 am Toasted TV Toasted TV Sunday 2020 3 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:30 am Transformers: Robots In Disguise (Rpt) G Collateral Damage Soundwave finally escapes the Shadowzone to set up a Beacon Generator intended to summon Megatron. -

THOMAS MARVEL Director of Photography 2821 3Rd Street Santa Monica, CA 90405

THOMAS MARVEL Director of Photography 2821 3rd Street Santa Monica, CA 90405 1986- Hamilton College, Clinton NY, Bachelor of Arts 1987- Grotowski Studio Theatre, Wroclaw, Poland 1987-1989 Production Assistant 1989-1994 Studio Lighting Technician 1994-1998 Chief Lighting Technician 1998- Present, Director of Photography 2015 NARRATIVE “The Nice Guys” Camera Operator, Directed by Shane Black, DP Philippe Rousselot COMMERCIALS Harbin Beer, “Shaq and Friends” directed by Gil Green MUSIC VIDEOS Mary J. Blige “Doubt” directed by Ethan Lader 2014 COMMERCIALS Sandals Foundation, “Soles of Youth” directed by Gil Green Mexico CPTM Tourismo, “Vivirlo para Creerlo” directed by Michael Abt Diners Club, “Club Miles” directed by Alejandro Dube Novo Nordisk, “Rev Run Diabetes Awareness” directed by Ron Jacobs Novo Nordisk , “Debbie Allen Diabetes Awareness” directed by Ron Jacobs Domino’s Pizza, “Must Try” directed by Francisco Pugliese MUSIC VIDEOS Wisin ft. Pitbull, “Control” directed by Carlos Perez Ricardo Arjona, “Apnea” directed by Carlos Perez 2013 NARRATIVE “The Veil” feature film directed by Brent Ryan Green COMMERCIALS Park Hyatt, “Anthem” directed by Josh Hayward Nissan, “Skylar Gray” directed by Declan Whitbeloom 1 Pepsi, “Wally Lopez” directed by Gil Green Sanofi Pasteur, “Dana Torres PSA” directed by Ron Jacobs YouTube, “Comedy Week Promo with Arnold Schwarzenneger” directed by Nick Ryan Tigo, “Verdades” directed by Roberto Mancia Valspar Paint, “Tori and Dean” directed by Natalie Barandes WalMart, “Gain” directed by Francisco Pugliese -

2021 Cadillac XT4 Owner's Manual

21_CAD_XT4_COV_en_US_84533014B_2020OCT27.pdf 1 9/25/2020 1:45:28 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 84533014 B Cadillac XT4 Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada/Mexico- 14584367) - 2021 - CRC - 10/14/20 Introduction model variants, country specifications, Contents features/applications that may not be available in your region, or changes Introduction . 1 subsequent to the printing of this owner’s manual. Keys, Doors, and Windows . 6 Refer to the purchase documentation Seats and Restraints . 36 relating to your specific vehicle to Storage . 84 confirm the features. Instruments and Controls . 90 The names, logos, emblems, slogans, Keep this manual in the vehicle for vehicle model names, and vehicle quick reference. Lighting . 129 body designs appearing in this manual Infotainment System . 136 including, but not limited to, GM, the Canadian Vehicle Owners GM logo, CADILLAC, the CADILLAC Climate Controls . 197 A French language manual can be Emblem, and XT4 are trademarks and/ obtained from your dealer, at Driving and Operating . 203 or service marks of General Motors www.helminc.com, or from: LLC, its subsidiaries, affiliates, Vehicle Care . 281 or licensors. Propriétaires Canadiens Service and Maintenance . 357 For vehicles first sold in Canada, On peut obtenir un exemplaire de ce Technical Data . 370 substitute the name “General Motors guide en français auprès du ” Customer Information . 374 of Canada Company for Cadillac concessionnaire ou à l'adresse Motor Car Division wherever it suivante: Reporting Safety Defects . 384 appears in this manual. Helm, Incorporated OnStar . 387 This manual describes features that Attention: Customer Service Connected Services . 392 may or may not be on the vehicle 47911 Halyard Drive because of optional equipment that Plymouth, MI 48170 Index . -

United States District Court Eastern District Of

Case 2:13-cv-05463-KDE-SS Document 1 Filed 08/16/13 Page 1 of 118 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA PAUL BATISTE D/B/A * CIVIL ACTION NO. ARTANG PUBLISHING LLC * * SECTION: “ ” Plaintiff, * * JUDGE VERSUS * * MAGISTRATE FAHEEM RASHEED NAJM, P/K/A T-PAIN, KHALED * BIN ABDUL KHALED, P/K/A DJ KHALED, WILLIAM * ROBERTS II, P/K/A RICK ROSS, ANTOINE * MCCOLISTER P/K/A ACE HOOD, 4 BLUNTS LIT AT * ONCE PUBLISHING, ATLANTIC RECORDING * CORPORATION, BYEFALL MUSIC LLC, BYEFALL * PRODUCTIONS, INC., CAPITOL RECORDS LLC, * CASH MONEY RECORDS, INC., EMI APRIL MUSIC, * INC., EMI BLACKWOOD MUSIC, INC., * FIRST-N-GOLD PUBLISHING, INC., FUELED BY * RAMEN, LLC, NAPPY BOY, LLC, NAPPY BOY * ENTERPRISES, LLC, NAPPY BOY PRODUCTIONS, * LLC, NAPPY BOY PUBLISHING, LLC, NASTY BEAT * MAKERS PRODUCTIONS, INC., PHASE ONE * NETWORK, INC., PITBULL’S LEGACY * PUBLISHING, RCA RECORDS, RCA/JIVE LABEL * GROUP, SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC., SONY * MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT DIGITAL LLC, * SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING, LLC, SONY/ATV * SONGS, LLC, SONY/ATV TUNES, LLC, THE ISLAND * DEF JAM MUSIC GROUP, TRAC-N-FIELD * ENTERTAINMENT, LLC, UMG RECORDINGS, INC., * UNIVERSAL MUSIC – MGB SONGS, UNIVERSAL * MUSIC – Z TUNES LLC, UNIVERSAL MUSIC * CORPORATION, UNIVERSAL MUSIC PUBLISHING, * INC., UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL * PUBLISHING, INC., WARNER-TAMERLANE * PUBLISHING CORP., WB MUSIC CORP., and * ZOMBA RECORDING LLC * * Defendants. * ****************************************************************************** Case 2:13-cv-05463-KDE-SS Document 1 Filed 08/16/13 Page 2 of 118 COMPLAINT Plaintiff Paul Batiste, doing business as Artang Publishing, LLC, by and through his attorneys Koeppel Traylor LLC, alleges and complains as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. This is an action for copyright infringement. -

Full Beacher

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 37, Number 18 Thursday, May 13, 2021 A League of Her Own by William Halliar Betsy Jochum always bat at Playland Park follow- loved outdoor sports. ing three seasons at Bendix Born in Cincinnati on Feb. Field. Due to COVID-19, 8, 1921, and growing up with however, attendance at the a brother, she learned early ceremony is limited to en- how to swing a stick or bat sure proper pandemic safety to strike rocks or worn-out measures. leather ball, to run bases on America’s love affair with a sandlot with the best and baseball, especially the toughest boys. game’s origin, is shrouded On May 17, 1943, Jochum in some mystery, as befi ts was among 280 women who any good romance. Games showed up at Chicago’s Wrig- with balls struck by sticks ley Field for consideration were played for centuries in the new All-American in Great Britain, Ireland Girls Professional Baseball and across Europe. The League. She was one of the rules varied, but many such 60 original players chosen games included running be- that spring day. From there, tween or around bases. And, she headed to South Bend they were imported to our for a career that defi ned the shores with the waves of im- rest of her life. migrants in the early 19th Now 100, Jochum has century. played a role in a new per- New York in the early manent exhibit honoring the 1800s was a crowded, bus- AAGPBL at South Bend’s tling, dirty, but without a The History Museum, 808 doubt energetic city. -

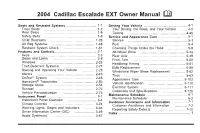

2004 Cadillac Escalade EXT Owner Manual M

2004 Cadillac Escalade EXT Owner Manual M Seats and Restraint Systems ........................... 1-1 Driving Your Vehicle ....................................... 4-1 Front Seats ............................................... 1-2 Your Driving, the Road, and Your Vehicle ..... 4-2 Rear Seats ............................................... 1-6 Towing ................................................... 4-46 Safety Belts .............................................. 1-8 Service and Appearance Care .......................... 5-1 Child Restraints ....................................... 1-28 Service ..................................................... 5-3 Air Bag Systems ...................................... 1-48 Fuel ......................................................... 5-4 Restraint System Check ............................ 1-61 Checking Things Under the Hood ................. 5-8 Features and Controls ..................................... 2-1 All-Wheel Drive ........................................ 5-48 Keys ........................................................ 2-3 Rear Axle ............................................... 5-49 Doors and Locks ....................................... 2-8 Front Axle ............................................... 5-50 Windows ................................................. 2-25 Headlamp Aiming ..................................... 5-51 Theft-Deterrent Systems ............................ 2-27 Bulb Replacement .................................... 5-55 Starting and Operating Your Vehicle ..........