Underwater Expeditions Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Florida Diving Science and Safety Program AAUS STANDARDS for SCIENTIFIC DIVING

The University of Florida Diving Science and Safety Program AAUS STANDARDS FOR SCIENTIFIC DIVING 2019 1 FOREWORD Since 1951 the scientific diving community has endeavored to promote safe, effective diving through self-imposed diver training and education programs. Over the years, manuals for diving safety have been circulated between organizations, revised and modified for local implementation, and have resulted in an enviable safety record. This document represents the minimal safety standards for scientific diving at the present day. As diving science progresses so must this standard, and it is the responsibility of every member of the Academy to see that it always reflects state of the art, safe diving practice. American Academy of Underwater Sciences ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Academy thanks the numerous dedicated individual and organizational members for their contributions and editorial comments in the production of these standards. Revision History Approved by AAUS BOD December 2018 Available at www.aaus.org/About/Diving Standards 2 Table of Contents Volume 1 ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 1.00 GENERAL POLICY .........................................................................................................................7 1.10 Scientific Diving Standards .........................................................................................................................7 1.20 Operational Control -

How Do Scientists Explore Underwater Ecosystems?

LESSON 2 How do scientists Age 11-14 explore underwater 60 minutes ecosystems? Curriculum links Lesson overview • Understand the scale of coral Throughout this lesson students explore underwater habitats reefs and the purpose of the and begin to understand the importance of the XL Catlin XL Catlin Seaview Survey Seaview Survey. Students consider why exploration of this • Identify the challenges kind can be challenging for humans and learn dive signs so scientist working underwater face they can communicate on their virtual dive. During the virtual • Sort and classify species dive students use 360 virtual reality to explore this dynamic environment, identifying some of the species that live there. Students go on to classify these species and record the findings of their first dive. Resources Lesson steps Learning outcomes Slideshow 2: How do scientists 1. What is the ocean habitat like? explorer underwater (10 mins) ecosystems? Students are introduced to the coral • Know that we live on a ‘blue planet’ Student Sheet 2a: ocean through a quiz to understand Video reflection the scale and complexity of this • Name a variety of ocean habitats ecosystem. and species that live there Student Sheet 2b: Species card sort 2. How is the baseline survey being Student Sheet 2c: Dive created? (10 mins) log Students become familiar with • Describe the XL Catlin Seaview the XL Catlin Seaview Survey and Survey and its scientific aims Video: the scientific rational behind the What kind of people exploration. make up a coral expedition team? 3. How do scientists work underwater? (15 mins) Video: Students consider some of the • Understand the different What are dive signs and challenges scientists face working techniques scientists use to work what do they mean? in this environment and practice underwater Google Map: using dive signs to communicate. -

NIKONOS Speedlighf

Nikon NIKONOS Speedlighf INSTRUCTION MANUAL NOMENCLATURE _______ CD Synchro socket index Joint collar @ Flash head positioning index @ Joint plate ® i ion mark @ i ion mark (@I (J) Sensor socket ® ro socket ® Synchro socket cover Joint @ @ Snp,erllinlht Arm@ ® Camera plug and locking ring Grip @ Sensor holder socket O-rings and lubricant @ @ Sensor holder positioning pin @ Bracket slot @ Bracket screw @Bracket Arm knob @ @ Buckle lock/release latch Battery chamber cap index @ Target -light holder @ @ calculation dial screw ® Exposure calculation dial Exposure calculation dial ® Distance scale scale mode selector ® @ Distance lines T-S switch ®> @ Non-TTL auto shooting aperture scale @ Non-TTL auto shooting aperture index Power switch ® scale 2 CONTENTS _________ NOMENCLATURE . 2 FOREWORD .. ... .. ...... ........ .. ..... 4 PREPARATION .......... ................... 4-6 Examining and lubricating the O-rings ... .. 5 The O-rings and their sealing method .... 6 TIPS ON SPEEDLIGHT CARE. .. 7 BASIC OPERATIONS . .. ..... ............... 8-16 CONTROLS IN DETAIL . ......... .... .. .... 17-30 Bracket ... .. ... .. .... .... ... .. .. ... ... 17 Arm .... .. ... ....... .. .. .. .. .. 17 Joint . ....... .... .. .. ... 18 Close-Up Shooting in the Non-TTL Automatic Mode . .. 18 Synchro Socket . .. 19 Sensor Socket . .. 19 Sensor Unit SU-101 (Optional). ... .. ... ... 20 Synchronization Speed . .. ....... ........ 20 Shooting Mode Selector. .. 21 Exposure Calculation Dial . ... ... .. 22 TTL Automatic Flash Control . .... 22-23 Non-TTL Automatic -

Nikon Report2017

Nikon 100th Anniversary Special Feature A Look Back at Nikon’s 100-Year History of Value Creation Nikon celebrated the 100th anniversary of its founding on July 25, 2017. Nikon has evolved together with light-related technologies over the course of the past century. Driven by our abundant sense of curiosity and inquisitiveness, we have continued to unlock new possibilities that have shined light on the path to a brighter future, creating revolutionary new products along the way. We pride ourselves on the contributions we have made to changing society. Seeking to make our hopes and dreams a reality, the Nikon Group will boldly pursue innovation over the next 100 years, striving to transform the impossible of yesterday into the normal of tomorrow. We will take a look back at Nikon’s 100-year history of value creation. 1917 Three of Japan’s leading optical 1946 Pointal ophthalmic lens manufacturers merge to form is marketed a comprehensive, fully integrated Nikon’s fi rst ophthalmic lens optical company known as Nikon brand name is adopted for Nippon Kogaku K.K. small-sized cameras Pointal Oi Dai-ichi Plant (now Oi Plant) Tilting Level E and Transit G 1918 is completed 1947 surveying instruments are marketed Nikon’s fi rst surveying instruments after World War II MIKRON 4x and 6x 1921 ultra-small-prism binoculars are marketed Nikon Model I small-sized 1948 camera is marketed The fi rst binoculars developed, designed and manufactured The fi rst Nikon camera and the by Nikon fi rst product to bear the MIKRON 6x “Nikon” name Nikon Model I Model -

Ecological and Socio-Economic Impacts of Dive

ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF DIVE AND SNORKEL TOURISM IN ST. LUCIA, WEST INDIES Nola H. L. Barker Thesis submittedfor the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science Environment Department University of York August 2003 Abstract Coral reefsprovide many servicesand are a valuableresource, particularly for tourism, yet they are suffering significant degradationand pollution worldwide. To managereef tourism effectively a greaterunderstanding is neededof reef ecological processesand the impactsthat tourist activities haveon them. This study explores the impact of divers and snorkelerson the reefs of St. Lucia, West Indies, and how the reef environmentaffects tourists' perceptionsand experiencesof them. Observationsof divers and snorkelersrevealed that their impact on the reefs followed certainpatterns and could be predictedfrom individuals', site and dive characteristics.Camera use, night diving and shorediving were correlatedwith higher levels of diver damage.Briefings by dive leadersalone did not reducetourist contactswith the reef but interventiondid. Interviewswith tourists revealedthat many choseto visit St. Lucia becauseof its marineprotected area. Certain site attributes,especially marine life, affectedtourists' experiencesand overall enjoyment of reefs.Tourists were not alwaysable to correctly ascertainabundance of marine life or sedimentpollution but they were sensitiveto, and disliked seeingdamaged coral, poor underwatervisibility, garbageand other tourists damagingthe reef. Some tourists found sitesto be -

NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations Project (NEEMO) 15

National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations Project (NEEMO) 15 facts XV NASA possible t-shirt colors Space exploration presents many unique aquanauts, live in the world’s only undersea challenges to humans. In order to prepare laboratory, the Aquarius, located 3.5 miles astronauts for these extreme environments off the coast of Key Largo, Fla. in space, NASA engineers and scientists use comparable environments on Earth. Most underwater activities are One of the most extreme environments is accomplished by traditional scuba diving, the ocean. Not only is the ocean a harsh but divers are limited to specific amounts of and unpredictable environment, but it has time because of the risk of decompression many parallels to the challenges of living sickness (often called the “bends”). Based and working in space – particularly in on the depth and the amount of time spent destinations with little or no gravity, such as underwater, inert gases such as nitrogen asteroids. will build up in the human body. If a diver ascends out of the water too quickly, the The NASA Extreme Environment Mission gases that were absorbed can create Operations project, known as NEEMO, bubbles within the diver’s body as the sends groups of astronauts, engineers, surrounding pressure reduces. doctors and professional divers to live in an underwater habitat for up to three weeks A technique known as saturation diving at a time. These crew members, called allows people to live and work underwater for days or weeks at a time. After twenty four hours Station, which has served as the living quarters for at any underwater depth, the human body becomes Expedition crew members. -

Underwater Photography Made Easy

Underwater Photography Made Easy Create amazing photos & video with by Annie Crawley IncludingIncluding highhigh definitiondefinition videovideo andand photophoto galleriesgalleries toto showshow youyou positioningpositioning andand bestbest techniques!techniques! BY ANNIE CRAWLEY SeaLife Cameras Perfect for every environment whether you are headed on a tropical vacation or diving the Puget Sound. These cameras meet all of your imaging needs! ©2013 Annie Crawley www.Sealife-cameras.com www.DiveIntoYourImagination.com Edmonds Underwater Park, Washington All rights reserved. This interactive book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, Dive Into Your Imagination, LLC a company founded by Annie Crawley committed to change the way a new generation views the Ocean and themselves. Dive Into Your Imagination, Reg. Pat. & Tm. Off. Underwater Photography Made Easy shows you how to take great photos and video with your SeaLife camera system. After our introduction to this interactive book you will learn: 1. Easy to apply tips and tricks to help you create great images. 2. Five quick review steps to make sure your SeaLife camera system is ready before every dive. 3. Neutral buoyancy tips to help you take great underwater photos & video with your SeaLife camera system. 4. Macro and wide angle photography and video basics including color, composition, understanding the rule of thirds, leading diagonals, foreground and background considerations, plus lighting with strobes and video lights. 5. Techniques for both temperate and tropical waters, how to photograph divers, fish behavior and interaction shots, the difference in capturing animal portraits versus recording action in video. You will learn how to capture sharks, turtles, dolphins, clownfish, plus so much more. -

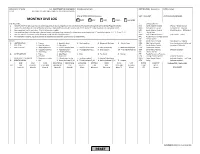

MONTHLY DIVE LOG ⃝ NMFS ⃝ NOS ⃝ OAR ⃝ OMAO ⃝ Non-NOAA

NOAA Form 57-10-24 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NAME (Last, First MI) CERTIFICATION (see note 1) DATE (mm/yy) (7-12) NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION LINE or STAFF OFFICE (Check one) UNIT / SUB-UNIT UNIT DIVING SUPERVISOR MONTHLY DIVE LOG ⃝ NMFS ⃝ NOS ⃝ OAR ⃝ OMAO ⃝ non-NOAA INSTRUCTIONS: 7. DIVE LOCATION 1. NOAA Form 57-03-24 (1-12) may be used to log dives in lieu of using the on-line, electronic form available through the NOAA Diving Program website. NAC North Atlantic Coastal (Maine – Rhode Island) 2. Submit this form directly to the NOAA Diving Center, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA, 98115 by the 5th of the month for the preceding month. MAC Mid-Atlantic Coastal (Connecticut – Virginia) 3. Use a separate line for each dive. Print all information legibly. SAC South Atlantic Coastal (North Carolina – SE Florida) 4. Log repetitive dives using the date, a decimal point, and consecutive numbers (i.e. three dives conducted on the 15th would be listed as 15.1, 15.2, and 15.3). KEY Florida Keys 5. Use the codes in the NOTES section below to encode the dive log information. GMC Gulf of Mexico Coastal (SW Florida – Texas) 6. For saturation missions, log all excursions as separate dives and time of excursions as bottom time. PVC Puerto Rico/U.S. Virgin Islands AKC Alaska Coastal NOTES: NPC North Pacific Coastal (Washington – Oregon) 1. CERTIFICATION 1 - Trainee 2 - Scientific Diver 3 - Working Diver 4 - Advanced Working 5 – Master Diver MPC Mid-Pacific Coastal (north and central California) 2. -

Dive Theory Guide

DIVE THEORY STUDY GUIDE by Rod Abbotson CD69259 © 2010 Dive Aqaba Guidelines for studying: Study each area in order as the theory from one subject is used to build upon the theory in the next subject. When you have completed a subject, take tests and exams in that subject to make sure you understand everything before moving on. If you try to jump around or don’t completely understand something; this can lead to gaps in your knowledge. You need to apply the knowledge in earlier sections to understand the concepts in later sections... If you study this way you will retain all of the information and you will have no problems with any PADI dive theory exams you may take in the future. Before completing the section on decompression theory and the RDP make sure you are thoroughly familiar with the RDP, both Wheel and table versions. Use the appropriate instructions for use guides which come with the product. Contents Section One PHYSICS ………………………………………………page 2 Section Two PHYSIOLOGY………………………………………….page 11 Section Three DECOMPRESSION THEORY & THE RDP….……..page 21 Section Four EQUIPMENT……………………………………………page 27 Section Five SKILLS & ENVIRONMENT…………………………...page 36 PHYSICS SECTION ONE Light: The speed of light changes as it passes through different things such as air, glass and water. This affects the way we see things underwater with a diving mask. As the light passes through the glass of the mask and the air space, the difference in speed causes the light rays to bend; this is called refraction. To the diver wearing a normal diving mask objects appear to be larger and closer than they actually are. -

2019 Weddell Sea Expedition

Initial Environmental Evaluation SA Agulhas II in sea ice. Image: Johan Viljoen 1 Submitted to the Polar Regions Department, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, as part of an application for a permit / approval under the UK Antarctic Act 1994. Submitted by: Mr. Oliver Plunket Director Maritime Archaeology Consultants Switzerland AG c/o: Maritime Archaeology Consultants Switzerland AG Baarerstrasse 8, Zug, 6300, Switzerland Final version submitted: September 2018 IEE Prepared by: Dr. Neil Gilbert Director Constantia Consulting Ltd. Christchurch New Zealand 2 Table of contents Table of contents ________________________________________________________________ 3 List of Figures ___________________________________________________________________ 6 List of Tables ___________________________________________________________________ 8 Non-Technical Summary __________________________________________________________ 9 1. Introduction _________________________________________________________________ 18 2. Environmental Impact Assessment Process ________________________________________ 20 2.1 International Requirements ________________________________________________________ 20 2.2 National Requirements ____________________________________________________________ 21 2.3 Applicable ATCM Measures and Resolutions __________________________________________ 22 2.3.1 Non-governmental activities and general operations in Antarctica _______________________________ 22 2.3.2 Scientific research in Antarctica __________________________________________________________ -

Underwater Welding Code

A-PDF Watermark DEMO: Purchase from www.A-PDF.com to remove the watermark D3.6M:2017 An American National Standard Underwater Welding Code http://www.mohandes-iran.com AWS D3.6M:2017 An American National Standard Approved by the American National Standards Institute January 10, 2017 Underwater Welding Code 6th Edition Supersedes AWS D3.6M:2010 Prepared by the American Welding Society (AWS) D3 Committee on Marine Welding Under the Direction of the AWS Technical Activities Committee Approved by the AWS Board of Directors Abstract This code covers the requirements for welding structures or components under the surface of water. It includes welding in both dry and wet environments. Clauses 1 through 8 constitute the general requirements for underwater welding, while clauses 9 through 11 contain the special requirements applicable to three individual classes of weld as follows: Class A—Comparable to above-water welding Class B—For less critical applications Class O—To meet the requirements of another designated code or specification http://www.mohandes-iran.com AWS D3.6M:2017 International Standard Book Number: 978-0-87171-902-7 © 2017 by American Welding Society All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Photocopy Rights. No portion of this standard may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, including mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Authorization to photocopy items for internal, personal, or educational classroom use only or the internal, personal, or educational classroom use only of specific clients is granted by the American Welding Society provided that the appropri- ate fee is paid to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, tel: (978) 750-8400; Internet: <www.copyright.com>. -

Final EIS Responses to Comments 1-40

Table 1-2. Responses to Comments Comment Response Comment/Response Number Number 1.1 The lakes in question are in our main camp area. We have operated in this area for thirty years and probably know more about the fish in these lakes than anyone associated with this ridiculous plan. These lakes have provided unequalled fishing to our guests and all others that have fished them. 1.1 This project is designed to preserve this stronghold for native westslope cutthroat trout. This project proposes to re-establish WCT populations in all treated lakes, which will maintain angling opportunities. 1.2 We feel that his plan goes against all that is held sacred in a wilderness area. … We believe the "Wilderness Act" should be respected and these areas should not be tampered with. 1.2 Native westslope cutthroat trout are considered a wilderness value. This project is designed to maintain and conserve that value. 1.3 Why should anyone be allowed to tamper with these healthy fish in order to obtain a genetically pure strain of fish? 1.3 It is the responsibility of MFWP to ensure that this species is conserved and maintained so the public of Montana can continue to use and enjoy it. The species has been at risk of hybridization for some time. MFWP has taken measures to reduce and eliminate the threats (see Section 1.2 of the DEIS). The species has been proposed for ESA listing (see Section 1.4.1 and Appendix B of the DEIS). MFWP is mandated to keep this from happening so the public does not lose the opportunity to use and enjoy WCT (see page 1-8 of the DEIS).